Books Reviewed

In the international academy, Sir Christopher Clark is as grand as it gets. The Australian historian made his name with Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947 (2006), which sought to demolish the idea that German history had followed a Sonderweg, or “special path,” culminating in the Nazis. A decade ago, The Sleepwalkers (2012), his history of the First World War, became a bestseller. In contrast to the “war guilt” clause of the 1919 Versailles Treaty and the Fritz Fischer thesis of the 1960s—that the Germans had deliberately planned and executed a war of aggression—Clark argued that all the great powers had “sleepwalked” into, and hence shared a degree of culpability for, the conflict. In the Anglophone world not everyone was convinced, but in Berlin the book was hailed as a masterpiece. It was required reading under Angela Merkel and still influences policy toward Russia under Olaf Scholz. Regius Professor of History at the University of Cambridge, knighted by the late Queen Elizabeth II, decorated with the Pour le Mérite (Germany’s highest civil honor), garlanded with numerous prizes and awards, Clark has reached the pinnacle of his profession.

***

His latest book is Revolutionary Spring: Europe Aflame and the Fight for a New World, 1848–1849, another hefty volume. Clark has a stirring story to tell about the revolutions which, beginning in Italy in January 1848, swept across Europe, and he tells it well. He is also an assiduous researcher, enabling him to unearth rich new sources. If his account falls short on the ideas that emerged from 1848, it makes up for it in marshalling the facts to evoke complex events in vivid detail.

The revolutions of 1848 brought many of the crowned heads of Europe to their knees. The Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand I told an emissary from his Hungarian subjects, “Please, I beg you, do not take away my throne.” (In the end, he did abdicate in favor of his nephew, Franz Joseph II, who reigned until 1916.) In fact, most revolutionaries had no wish to abolish Europe’s monarchies: they wanted constitutions, parliaments, a free press. France did become a republic, but it lasted only until 1852, when President Louis Napoleon declared himself the Emperor Napoleon III. Within a year of the uprisings of 1848 the tide had turned across the German, Italian, Magyar, and Slavic lands. This pan-European experiment in 57 varieties of democracy proved no match for the professional armies of the counterrevolution. Where elections were held, the people proved to be more conservative than their tribunes. But slogans such as “property is theft” from a radical minority enabled the forces of reaction to demonize liberals and social reformers as bloodthirsty class warriors. Few were actually “anarchists,” but it was they rather than the aristocrats who paid with their lives. The firing squads that crushed the hopes of 1848, however, fueled the inexorable rise of European socialism in the century that followed.

***

Like other great convulsions of modern history, the 1848 revolutions left Britain and the United States almost untouched. As a result, the uprisings are remembered, if at all, by the English-speaking peoples only by a handful of quotations. The revolutionary leaders—Louis Blanc, Robert Blum, even Giuseppe Mazzini and Lajos Kossuth—may have lacked the unforgettable charisma of Danton and Robespierre, but the minor players included several of the most influential political thinkers of all time.

Chief among these was, of course, Karl Marx. His most memorable work, The Communist Manifesto (with Friedrich Engels in 1848), is addressed to “the proletariat,” exhorting them to seize control of events from “the bourgeoisie” and culminating in the stirring cry: “The workers have nothing to lose in this [revolution] but their chains. They have a world to gain. Workers of the world, unite!”

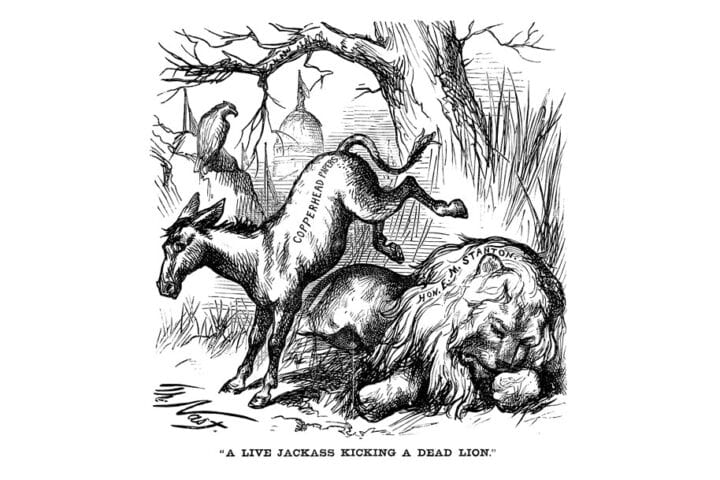

Marx got it badly wrong. His intended audience was not ready to embrace his “class war.” As politicians as different as Otto von Bismarck and Benjamin Disraeli would later demonstrate, many workers were quite conservative. Of the minority who followed the radical intellectuals in rejecting the compromises of a limited liberal democracy, thousands would die in the backlash of counter-revolution. In his bitter obituary on the failed revolutions of 1848, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx explained away his failed prophecy by arguing that it had all been a swindle. “Bourgeois republic” is actually the opposite of liberty and democracy, he argued; it “signifies the unlimited despotism of one class over other classes.”

The triumph of Louis Bonaparte, who emerged from the chaos first as the elected president of France, and then (after a coup d’état) as the Emperor Napoleon III, prompted Marx’s celebrated opening lines: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historical facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” When Marx’s Communist heirs got the revolutions they wanted in the 20th century, the word “tragedy” was barely adequate to describe the consequences. But there was a farcical aspect to Communism’s collapse in 1989. (Readers who don’t remember how “the dictatorship of the proletariat” ended might like to watch Turning Point: The Bomb and the Cold War, the Netflix documentary series expertly narrated by the historians Mary Elise Sarotte and Timothy Garton Ash.)

***

In Revolutionary Spring, Clark ignores these and other key passages from Marx and Engels. He is correct in assuming that hardly any of the actual revolutionaries had heard of these prophets or their effusions. He may also assume too much familiarity by his readers with Marx, who is no longer fashionable outside academic circles. But Clark’s downplaying of Marx’s role in shaping the legacy of revolution feels like a missed opportunity. After all, 1848 was the crucible from which Marxism emerged. And some of the horrors to come were already prefigured in the writings of Marx and Engels during the revolutionary period. These should not be ignored, given the endless atrocities later perpetrated in their names.

Engels, in particular, advocated an extreme form of social Darwinism avant la lettre. In 1849, as the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian armies moved across Central Europe, crushing uprisings as they went, the newspaper Die Neue Rheinische Zeitung published an article by Engels in which he insisted that only three nations in the Habsburg empire—the Germans, the Poles, and the Magyars—were “bearers of progress.” He explained: “All the other nations and peoples, large and small, are destined to disappear in the revolutionary world storm. That is why they are counter-revolutionary.” For Engels, such Völkerabfälle (variously translated as “racial trash” or “remnants of peoples”) welcomed “the Russian knout” and its reversal of the direction of European history from West to East. “The next world war will cause not only reactionary classes and dynasties, but entire reactionary nations to disappear from the face of the earth. And that too is progress.”

This and other such texts were rescued from the obscurity of defunct periodicals by the Communist historian Franz Mehring more than a century ago. Given the genocidal record of Stalin, Mao, and other dictators, up to and including Xi Jinping, a historian of the 1848 revolutions might have pondered the fact that the fons et origo of these crimes against humanity is to be found in the reaction of Marxism’s founders to their defeat. But Clark is no more interested in Marx or Engels than in their ideological rivals: the founder of anarchism, Mikhail Bakunin, has only a walk-on part; Moses Hess, who pioneered Zionism a generation before Theodor Herzl, gets barely a mention.

***

Alexis de Tocqueville receives rather more attention. Clark quotes Tocqueville’s magnificent warning to French ministers sitting in the Chambre des Députés on the eve of their overthrow in March 1848: “Do you not feel, by some intuitive instinct which is not capable of analysis, but which is undeniable, that the earth is quaking once again in Europe? Do you not feel…what shall I say?…as if a gale of revolution were in the air?”

The author of Democracy in America was far wiser than the author of The Communist Manifesto. He saw where the “class struggle” in which Marx exulted would lead, sooner rather than later: to carnage. Clark does not quote what Tocqueville wrote in May 1848 after the revolution, when he helped to draw up a new constitution for the Republic:

One thing was not ridiculous, but really ominous and terrible; and that was the appearance of Paris upon my return. I found in the capital a hundred thousand armed workers formed into regiments, out of work, dying of hunger, but with their minds filled with vain theories and visionary hopes. I saw society cut into two: those who possessed nothing, united in a common greed; those who possessed something, united in a common terror. There were no bonds, no sympathy between these two great sections; everywhere the idea of an inevitable and immediate struggle seemed at hand.

Once the struggle was over, with the reaction ascendant across Europe, many erstwhile revolutionaries emigrated to the New World. Others sought asylum in England, where they might (like the Hungarian tribune Lajos Kossuth) be fêted by multitudes, or perhaps lose themselves in an underworld of spies and conspiracy theorists. (Marx himself only partially escaped this fate.) Clark devotes a chapter to these tens of thousands of émigrés, who would leave their mark across the globe.

Though Clark fails to do justice to the ideas of 1848, he allows us to hear the voices of participants who have hitherto been drowned out. For minorities in Europe, such as the Jews, or enslaved populations in the colonies, 1848 brought emancipation and abolition. For women, though, it was largely a matter of “waving from windows.” Clark breaks new ground by showing 1848 from a female perspective—a perspective that is often more detached and sharper than the partisan male one. The American journalist and diarist Margaret Fuller, for example, provided the best eyewitness accounts of the rise and fall of the Roman Republic—though her view of the gaunt figure of Mazzini, its leader, as “[b]y far the most beauteous person I have seen,” is baffling. The best French contemporary history was by Marie Countess d’Agoult, who wrote under the pen name Daniel Stern. By one of the ironies of an era replete with them, her illegitimate daughter by Franz Liszt, Cosima, married the disillusioned revolutionary Richard Wagner, nurtured his festival at Bayreuth, and lived until 1930—by which time the Wagner cult had been co-opted by Adolf Hitler.

***

Clark concludes his book by reflecting on its lessons for the present. In 1848, Americans watched from afar as Continental Europe’s experiment in democracy, in Clark’s words, “closed itself down.” But though they were spared the revolutionary chaos across the Atlantic, they did not have to wait long for an even more terrible Civil War to erupt in their own back yard.

“I was struck by the feeling that the people of 1848 could see themselves in us,” Clark writes, adding: “The storming of the Capitol on 6 January 2021 in Washington DC was thick with echoes [of 1848].” Not all CRB readers will agree with this implied criticism of Donald Trump. But those who watched the events of that day unfold on television may have shared Tocqueville’s bemusement at the outbreak of revolution on February 25, 1848: “Throughout this day in Paris, I never saw one of the former agents of authority: not a soldier or a gendarme or a policeman; even the National Guard had vanished.”

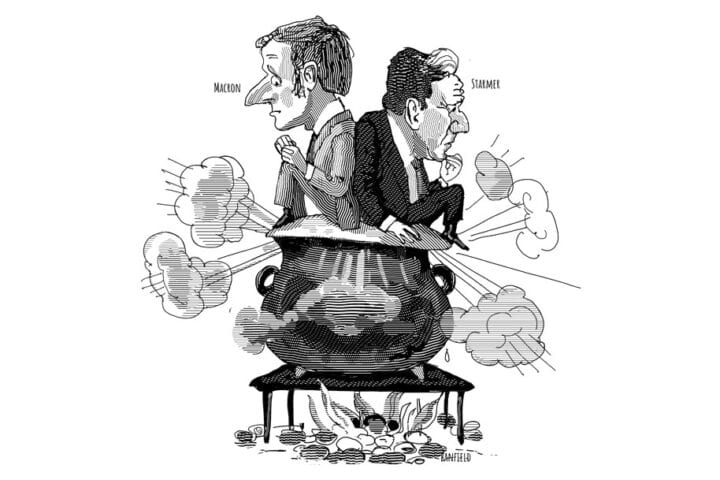

If such comparisons make for uncomfortable reading, it is well to be prepared for Tocqueville’s gale to blow again. An already profoundly polarized United States enters an election season fraught with “known unknowns” (Harris and Trump) but also “unknown unknowns.” In the heat of summer, the spring wave of campus protests may overflow onto the streets. Europe, too, is “aflame.” British historian Lewis Namier called the struggles of 1848, “the revolution of the intellectuals.” This fall could well witness a revolution against the intellectuals.