Here is a curious coincidence: over the New Year, two remarkable films were released here in the U.S., Cold War (Zimna wojna) by Polish director Pawel Pawlikowski and Never Look Away (Werk ohne Autor) by German director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. Both were written and directed by gifted auteurs hoping for a new success after a previous film garnered wide acclaim and won an Academy Award. (In Pawlikowski’s case, 2013’s Ida; in Donnersmarck’s, 2006’s The Lives of Others.) Both are set in Europe between the 1930s and 1960s, and without indulging in simplistic moral judgments, both ask us to contemplate the political, philosophical, and psychological schisms dividing East from West during those years. And perhaps most curious, both directors contemplate this complex period through the prism of art.

Love or Freedom?

In Cold War, the prism is music. The film opens in a war-ravaged village in the Mazowsze region of northwest Poland. A classical pianist called Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) and a folklorist called Irena (Agata Kulesza) are recruiting singers and dancers for a folk ensemble sponsored by the newly installed Communist regime. The most impressive talent they find is a young woman, Zula (Joanna Kulig), who has spent time in prison because, as she defiantly tells Wiktor, her father “mistook me for my mother, so I used a knife to show him the difference.”

Zula quickly becomes the star of the troupe, which is modeled on a famous Soviet-era ensemble called Mazowsze. One of the musical high points is a gorgeous arrangement of the folk song “Dwa serduszka” (“Two Hearts”), sung in close harmony by Zula and another woman backed by a chorus. Wiktor and Zula fall passionately in love, the ensemble is rewarded with a tour of the Warsaw Pact countries, and all goes well until Mazowsze is stripped of its authentic Polish soul. Repurposed as an ideologically correct “people’s chorus,” the troupe appears before the Great Leader of Mankind performing a lifeless hunk of sound called “The Stalin Cantata.”

By 1961, Wiktor is fed up and, having acquired a taste for jazz, waits until the troupe is performing in East Berlin to beg Zula to cross with him into the West. The wall is about to be built, so it is now or never. Zula agrees, but when she fails to appear at the designated time, Wiktor must choose: love or freedom? He chooses freedom, and while the couple meet intermittently for the next few years and make love as ardently as ever, they no longer trust each other. Wiktor settles in Paris, drifting from affair to casual affair, and feeling the way Pawlikowski recalled feeling during his first Paris sojourn—like “a lost guy in a weird city.”

Zula eventually joins Wiktor, but despite achieving modest success as a Parisian chanteuse, she is chronically depressed. On one occasion the old defiant spirit breaks out again: in a nightclub, where Zula is drunk and nodding off at the bar, someone puts on “Rock Around the Clock,” the 1955 hit record by Bill Haley & His Comets. As the crowd starts to dance, Zula rises up like a jitterbugging phoenix, leaving behind the ashes of her mood. But this brief liberation does not repair things with Wiktor, because as Pawlikowski explained elsewhere, the incident “plants a wedge between them because she reacts to the song, and Wiktor doesn’t.”

After that, Zula retreats to Poland, where, having run out of better choices, she marries Lech Kaczmarek (Borys Szyc), the party apparatchik who masterminded Mazowsze’s transformation into a propaganda machine. Wiktor follows her but is thrown in prison for entering the country without papers. Zula uses her connections to get Wiktor released, and the lovers are once again reunited.

Proximity only deepens the lovers’ gloom, however, and the film ends with them making a pilgrimage to a bombed-out church they visited in earlier, happier days with the folk troupe. Kneeling before what is left of the altar, Wiktor and Zula perform a do-it-yourself wedding ceremony, followed by the ritual swallowing not of communion wafers but of a score of white pills clearly intended to cause death. Pawlikowski dedicates the film to his parents. But surely his parents did not die in a mock communion following a mock marriage. Why make the ending so dark?

The Holy Spirit of the Whole Story

A partial explanation may be found in the controversy that arose around Ida, Pawlikowski’s Oscar-winning film about a young novitiate in a Polish convent who discovers that she is Jewish, that her family perished in the Holocaust, and that her one remaining relative, an aunt, is a former Communist judge notorious for her harsh and arbitrary punishments. The aunt has now shown up at the convent insisting that, before Ida takes her final vows, the two of them go on a journey to find out what happened to their family.

In Poland, Ida proved a volatile mix. Amid accusations of anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism, and collaboration with the Nazi and Communist regimes, Pawlikowski found himself telling an interviewer that his own background was a mixture of Catholic, Jewish, and secular—and that most of his father’s family “had disappeared” in the war. Regarding his own beliefs, he told the same interviewer that he had

rediscovered religion for myself, strangely, when I was living abroad and met a very wise Dominican priest. I’m not deeply religious, but I’m definitely part of that electro-magnetic field. It’s something that helps me define myself a little, not in terms of identity…but, well, let’s just say that Christ’s teachings are not irrelevant.

I cannot fault Pawlikowski for walking on eggshells when it comes to the agonies of his country’s recent history. But I do wonder: is he walking on eggshells in Cold War? To take religion seriously can be risky for a filmmaker in contemporary Europe. So perhaps he decided to make the ending as dark as possible, but also to include a few cryptic details hinting at a different interpretation. At the risk of scrambling my metaphors, the current fashionable term for such details is “Easter eggs.” Derived from the phrase “Easter egg hunt,” the term has no discernible religious meaning for the digital natives who use it in the context of computer programs, videogames, and other media. But perhaps it does here.

“Music became the holy spirit of the whole story,” says Pawlikowski about Cold War. Thus, it matters that he rejected the music originally composed for the final credits, because he found it too sad. Too sad, when the last thing the doomed lovers do is cross the road so they can die with a “better view”? Even without judging suicide a sin, it is hard to see anything redeeming here. Yet the director’s stated reason for substituting a different piece of music—Glenn Gould’s recording of the “Aria” from Bach’s Goldberg Variations—is that it expresses “reconciliation with life—even if it’s afterlife.”

If this choice of music is an Easter egg in a different sense, containing a hidden affirmation of Christian hope, then perhaps we should hunt for others. For example, from inside the bombed-out church the camera pans upward to the jagged hole where the dome once was, revealing a circle of open sky fringed by treetops. The sight is beautiful, perhaps more beautiful than when the dome was intact. Similarly, on a crumbling wall containing a ruined fresco, the camera reveals what is left: a pair of human eyes, gazing gently, I’m tempted to say mercifully, into the rubble-strewn space. And finally, the road crossed by Wiktor and Zula runs in front of the church. So perhaps by crossing it the lovers ensure that their last sight on earth will be of a holy place, instead of an empty field.

The Aristocrat and the Artist

The six-foot-nine-inch-tall scion of a once-mighty aristocratic family driven off its ancestral land in Silesia by the Red Army in 1945, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck is not afraid to walk on eggshells. He has made three major films: The Lives of Others (Die Leben Der Anderen) in 2006; The Tourist in 2010; and Never Look Away.

The most renowned is The Lives of Others, about a dour, meticulous Stasi agent in the 1980s (played brilliantly by the East German stage actor Ulrich Mühe) who sacrifices his career to save a prominent playwright and actress from being arrested for “political crimes.” Despite its renown, the film stirred controversy in Germany and was boycotted by several major film festivals, including the Berlinale. According to a profile of the director by New Yorker writer Dana Goodyear, “Easterners who had been oppressed by the Stasi found the character of the agent too sympathetic; those who hadn’t been oppressed said the whole thing was sensationalized.”

It didn’t help that after winning the Oscar, Donnersmarck went Hollywood. The Tourist, which he co-wrote and directed on a $100 million budget, starred Angelina Jolie and Johnny Depp as a glamorous spy and her dorky lover chasing bad guys through some of the most expensive locations in Venice. Not as dreadful as the critics said, The Tourist grossed $278 million at the global box office. But coming from a director who had made his name stirring up serious political debates in Europe, this glitzy bauble was a shocker.

Now Donnersmarck is back in highbrow territory. Never Look Away is a three-hour, visually luxuriant epic about a fictional German artist called Kurt Barnert (played by child actor Cai Cohrs, then Tom Schilling). Born in Dresden just before World War II, Kurt experiences the trauma of the early Nazi period, then participates in some of the most important art-historical events of the next 30 years, including the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibitions organized by the Nazis to expose the German public to the purported dangers of modernist art; the imposition of Socialist Realism on the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden, under East German Communist rule; and finally the absurdist, often absurd, experiments of the West German avant-garde in early 1960s Düsseldorf.

The story is based loosely on the life of Gerhard Richter, one of the most famous German artists of his generation. (Richter is the source of the film’s German title, “Work without Author.” He once said that about art, but to judge by his overall conduct regarding his work and reputation, he did not mean it.) Donnersmarck spent many hours interviewing Richter and consulting with Dietmar Elger, director of the Richter archive and author of an authorized biography, as well as with Jürgen Schreiber, an investigative journalist and author of an unauthorized but respected biography. But Donnersmarck also changed many details for the sake of the story. As he commented to a reporter, “If you look at something like ‘Citizen Kane,’ it’s pretty clear that was inspired by William Randolph Hearst, but on a certain level I would find it less appealing if it were called ‘Citizen Hearst’ and not ‘Citizen Kane.’”

Donnersmarck’s changes must have displeased Richter, because when Never Look Away was released, the artist denounced it, while also declaring he had no plans to see it. Asked about this, the director sounded a charitable note:

I’d been warned by his biographer that he always turns on people after opening up to them…. But in a way, I also understand him because it’s about a lot of traumatic things, many of which have happened in his life…. [M]aybe the film is for everybody except for him.

An Aunt Judged “Unworthy of Life”

Unfortunately, not everybody went to see Never Look Away. Compared to Cold War, it did rather poorly at the box office. Richter’s denunciation, rippling through the media in Germany and beyond, surely had a dampening effect. But even without that response, it is hard to imagine a groundswell of enthusiasm for a film that departs as drastically as this one does, not only from the standard narrative of mid-20th-century totalitarianism, but also from the accepted definition of art in the modern age.

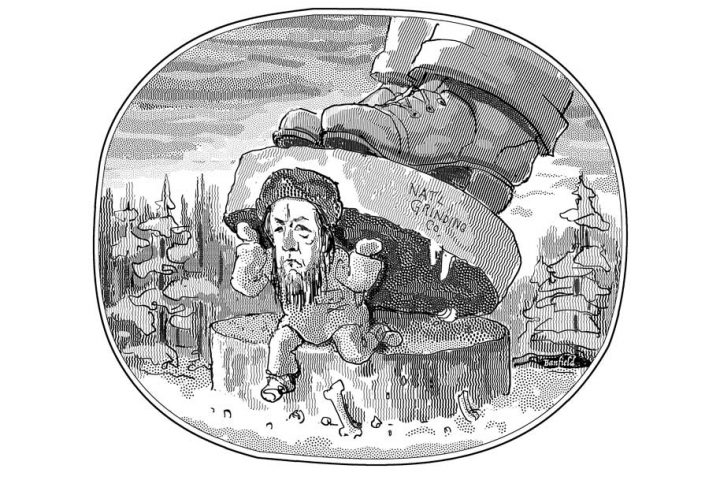

To begin with the standard narrative: this is the only film I can think of that portrays the Third Reich without mentioning the fate of the Jews. The reason may be the timing of an incident that provides the film’s moral fulcrum: the death of Richter’s beloved aunt at the hands of Nazi eugenicists. The Nazi campaign to “purify” the “Aryan race” killed millions of Jews, Roma, Slavs, and other groups classified as “racially inferior.” But as noted on the website of the U.S. Holocaust Museum, the first wave of victims were German citizens:

The Euthanasia Program…predated the genocide of European Jewry (the Holocaust) by approximately two years. The program was one of many radical eugenic measures which aimed to…eliminate what eugenicists and their supporters considered “life unworthy of life”: those individuals who—they believed—because of severe psychiatric, neurological, or physical disabilities represented both a genetic and a financial burden on German society and the state…. The Euthanasia Program represented in many ways a rehearsal for Nazi Germany’s subsequent genocidal policies…. Planners of the “Final Solution” later borrowed the gas chamber and accompanying crematoria, specifically designed for the T4 [Euthanasia] campaign, to murder Jews in German-occupied Europe. T4 personnel who had shown themselves reliable in this first mass murder program figured prominently among the German staff stationed at the Operation Reinhard killing centers of Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.

In the film, Kurt’s aunt is named Elisabeth (Saskia Rosendahl), and it is she who takes him to the Degenerate Art Exhibition and, ignoring the guide’s robotic lecture about the evils of Grosz, Klee, Picasso, Chagall, Kandinsky, and other modernist masters, whispers in his ear: “Never look away. Everything true is beautiful.” The words stick, not because they are an accurate description of reality, but because Kurt adores his Aunt Elisabeth with an intensity both erotic and innocent. When she has a mental breakdown after being chosen to hand a bouquet to the Führer, and is carted off to an “asylum” that is really the portal to sterilization and eventual murder, Kurt is traumatized.

The trauma continues with the Allied firebombing of Dresden and the suicide of Kurt’s father, a humane schoolteacher who was forced by the Nazis into joining the party, then punished by the Communists with a humiliating job scrubbing stairs in the rundown building where his family lives. The same job is later foisted on Kurt by his evil father-in-law, Carl Seeband (Sebastian Koch), a Nazi doctor who survived by ingratiating himself with a Soviet general and now poses as a loyal Communist but is still a diehard Nazi. When his daughter Ellie (Paula Beer) marries Kurt, a low-born art student whose own father hung himself, Seeband does everything he can to protect his precious bloodline—including abort his own grandchild.

What the young lovers do not know, but we do, is that Seeband is the stone-cold eugenicist who sent Kurt’s Aunt Elisabeth to her death. I don’t want to spoil the ending, but the rest of Never Look Away is a strange sort of detective story, in which the main character is not a sleuth trying to solve a crime but rather a troubled young artist seeking a genuine source of inspiration in a world that no longer believes in such things. By succeeding in the latter quest, Kurt also succeeds in the former.

The Code of the World

Kurt’s artistic breakthrough occurs at the venerable Art Academy in Düsseldorf, which in the early 1960s was in full revolt against the past. In a telling exchange, a fellow student also from the east says to Kurt, “You can do anything you like”; and Kurt replies, “If only I knew what that was.” The school buzzes with performance art, dribble painting, body painting, canvases slashed, canvases covered with wallpaper, heavy wooden furniture with hundreds of nails sticking out of it—everything except traditional easel painting, the one thing Kurt is good at. Presiding over the scene is Antonius van Verten (Oliver Masucci), a fictional clone of Joseph Beuys, a protean conceptual artist known mainly for his gleeful exploding of all accepted truths, especially those relating to art.

After dismissing Kurt’s feeble efforts to be avant-garde, van Verten confides in him with a story identical to the one told by Beuys about having served in a bomber crew during the war, and when his plane was shot down over Crimea, having been badly injured and unconscious. The point is that Beuys would have died had it not been for some Tatar nomads who rescued him, wrapped his freezing body in thick felt and animal fat, and nursed him back to health. At the end of this tale, van Verten says to Kurt, “I am not Descartes. For me, the truth is grease and felt…. What are you?”

Taking the question to heart, Kurt begins feeling his way, guided by an elusive Muse who resembles his Aunt Elisabeth, toward a moment of inspiration that comes after a glum dinner with Seeband, his father-in-law, which is interrupted by a boy entering the restaurant with newspapers reporting the arrest of Seeband’s old boss, the head of the Euthanasia Program in Dresden. Seeband departs hurriedly, leaving behind the newspaper with the photo of the killer. Kurt takes it to his studio, and begins the delicate work of turning this photo and many others, including old family snapshots and portraits, into vivid paintings which he then blurs slightly with his brush, evoking the fading of memory over time.

Paradoxically, the effect of this work is that Kurt recovers not only Elisabeth’s memory but also her intensity of perception and emotion, including her capacity to become lost in ecstatic visions of what the German Romantics called the Sublime. These visions have occurred before in the film. On one occasion, Elisabeth persuades a group of idling bus drivers to sound their horns in unison, sending her into a trance. (I am not sure this scene would work without the assistance of some evocative music.) On another, Kurt leaps from his perch in a magnificent old tree and runs through a field of golden wheat to his parents’ house, crying, “All is connected! I have discovered the code of the world! I am untouchable!” And in the final scene, Kurt persuades a new generation of bus drivers to sound their horns (to the same evocative music).

When Art Does Not Boast

The romantic sublime is not a big item in the art of present-day Europe, needless to say. Especially in Germany, most educated people consider the whole idea of art being uplifting or transcendent verboten. This is because of the association of that idea with the Große Deutsche Kunst (Great German Art) churned out by state artists under the direction of Hitler, Goebbels, and their cultural henchmen. It is not illegal in Germany to show images of this art—vast canvases of snow-covered Alps, flaxen-haired children, and chilly female nudes; massive sculptures of wasp-waisted warriors with blank eyes and bulging muscles; innumerable heroic portraits of der Führer—but it is definitely discouraged.

Why does Donnersmarck go against this consensus? My guess is that he feels a certain weariness with the standard alternative to the Romantic Sublime, which is the radicalism of the postwar avant-garde, embodied in a figure like Joseph Beuys. One thing I found puzzling about Never Look Away was the inclusion of Beuys’s story about having been saved by Tatar nomads in the Crimea. It is now well established that this story is a complete fabrication. Beuys’s plane was shot down, but German military records indicate that his injuries were not serious, that he was conscious, and that he was soon rescued by a search commando unit which brought him to a field hospital, where he recovered in three weeks. There were no Tatar nomads in the area at the time.

My guess is that Donnersmarck included Beuys’s whopper to shame the post-World War II art world for having embraced it so uncritically. As noted recently in the Guardian, Beuys’s admirers defended the story even after it was proven false, calling it the “self-creation” of a “self-styled shaman” fascinated with “transformation, the alchemy of one thing turning into another” and experience “transfigured into myth.” This sounds impressively postmodern. But what about the lies told by former Nazis after World War II? Were they also fascinated with the alchemy of one thing turning into another? And what about Holocaust deniers? Are they also transfiguring experience into myth? Maybe exploding the truth is not such a good idea.

A number of critics have faulted Never Look Away for being “too ambitious.” What they mean is that a filmmaker would have to be crazy to make a three-hour movie dramatizing what happened to Western art over the course of the 20th century. But consider: would those same critics consider it crazy to make a three-hour movie lionizing Joseph Beuys for having boasted repeatedly that, as an artist, he possessed the power to transform the world?

What Donnersmarck does in Never Look Away is highly unusual and much needed. He draws a parallel between three such boasts: the Nazi boast about Great German Art; the Soviet boast about Socialist Realism (which started before the Nazi era and lasted much longer); and the postwar avant-garde boast about its own radical gestures, most of which were recycled from prewar art movements such as Futurism, Expressionism, Dadaism, and Surrealism. Compared to these, the Romantic Sublime looks downright modest. All it wants to do is make beauty.

Despite the Nazis’ preposterous appropriation of beauty as marker of racial superiority, Donnersmarck is not afraid to include it in this film. This is because, as the film shows it, the beauty of Kurt’s art is what finally blows Seeband’s cover. Walking into Kurt’s studio where several of the photo-paintings are arrayed in seemingly random order, Seeband stops in his tracks. For him, the order is not random. He sees, and we see, how the paintings trace the relationships between him, his former boss the war criminal, the young woman he sent to the gas chamber years ago, and his son-in-law. Like a body whose soul has been sucked out by a demon, Seeband crumples and edges out of the room, leaving Kurt standing in a beam of sunlight with a quizzical expression on his face.

In a brilliant and essential plot twist, neither Kurt nor Ellie ever realizes the truth about Seeband’s responsibility for Elisabeth’s death. But by being true to each other and resisting his pernicious influence, they succeed in shattering his pride. It is a beautiful thing to see, and the joy that follows feels a lot like redemption.