What was the countercultural culture that lasted for a decade or two after the 1960s? To those who rallied behind it, it was a progressive reworking of old values, a drawing out of new possibilities. To those who lamented it, it was a mere looting of the old culture, a decadence, a spending down. In theory it could have been both at the same time. But by the 1970s, Americans were reaching a verdict. They were drifting away from the idea that the country was in the middle of a renaissance and beginning to worry that it was going down the tubes.

This was not just a reaction to a slowing economy. Certainly, in an economy hemmed in by strong trade unions, new environmental regulation, and newly expensive oil and gasoline, it seemed impossible to create jobs. In December 1974 alone, the country lost 600,000 of them. But Americans were concerned more about the culture than the conjuncture.

American automobiles had once been a symbol of the country’s world-bestriding economy. Now their shoddiness was astonishing, embarrassing, no matter how obstreperously auto workers demanded to be compensated as the “best workers in the world.” In 1977, Plymouth brought out a new “T-Bar coupe” called the Volare. “To the new generation of Americans who have never known the driving pleasure of wind through the hair,” the ads ran, “we proudly dedicate our new T-Bar Volare Coupe.” It was a way for Chrysler to avoid saying that it had lost the capacity to build convertibles at an affordable price. Starting in 1978, General Motors began producing station wagons—such as the Buick Century and the Oldsmobile Cutlass Cruiser—in which the rear windows didn’t roll down. Magazine ads for Ford and Cadillac depicted their new models against a dim backdrop of historic ones, as if to console themselves that, if their products were third-rate, they had at least once made better ones.

The prospects for government were, if anything, worse. It was not only that Richard Nixon had been forced from office in a scandal. The three great progressive endeavors of the preceding decades—civil rights, women’s liberation, the attempt to impose a liberal order on the world militarily—had all been resoundingly repudiated by the public. Post-Civil Rights Act, violent crime and drug abuse in inner cities were at record highs. Post-Ms. magazine, legislatures were rescinding ratifications of the Equal Rights Amendment that they had only recently passed. Post-Vietnam War, Soviet troops entered Afghanistan and revolutionary governments came to power in Nicaragua and Iran.

The mood was one of nostalgia and failure. The American public had come to see the political project of the 1960s as dangerously utopian. They brought California governor Ronald Reagan to power to put an end to it. Instead, in ways that neither his supporters nor his detractors have ever fully understood, he rescued it.

What Did the Debt Buy?

Dwight eisenhower warned in his 1961 farewell address, “We—you and I, and our government—must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow.”

By then the country had known massive borrowing, but only in wartime. To fight World War II, the federal government had added $200 billion to its debt—an amount that by war’s end was about the size of the gross domestic product. Although the size of the total credit market (including private individuals) would expand every single year from 1947 to 2008, in the first 35 years after World War II the trajectory of government debt (measured as a percentage of gross domestic product) had steadily declined. Under Reagan it began to rise. In fact, the national debt would triple on his watch. That opened a new chapter in American fiscal history.

Looking at numbers and charts from the 1980s, it is easy to miss the most basic question: Why on earth, at the height of the Baby Boom generation’s productive years, did the government need to borrow in the first place? What did this binge of debt buy? What emergency did it extricate the country from?

From an actuarial and from a human-capital perspective, the quarter-century after Ronald Reagan’s election should have been the easiest time to balance the budget in the history of the republic. The entirety of the vast Baby Boom generation, making up 38% of the voting population, was in its productive years. There were relatively few retirees and dependent children to tend to. The country was (until the Iraq War after 2003) at peace. It set the rules for the global economy. But since Baby Boomers were due to leave the workforce between 2010 and 2030, big obligations for Social Security and Medicare loomed. Those would go unmet.

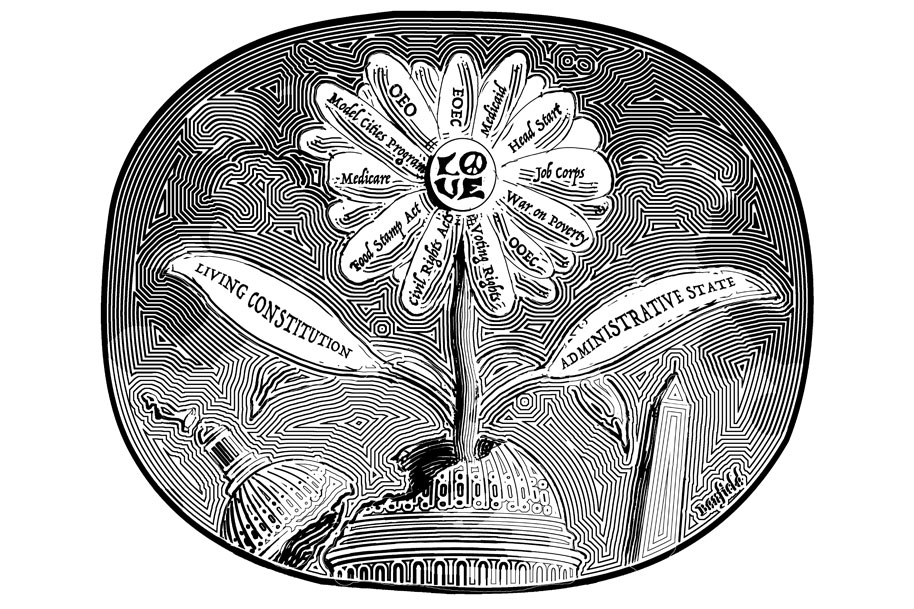

The borrowing power of the Baby Boom generation was invested in avoiding the choices that the confrontations of the 1960s had placed before the country. What the debt paid for was social peace, which had come to be understood as synonymous with the various Great Society programs launched by Lyndon Johnson in the two years after the Kennedy assassination. We should understand the Great Society as the institutional form into which the civil rights impulse hardened, a transfer from whites to blacks of the resources necessary to make desegregation viable. Desegregation was, as we have said, the most massive undertaking of any kind in the history of the United States. Like any massive undertaking, it required endurance, patience, and prohibitive expense. Almost everyone who did not benefit from it was going to be made poorer by it. Now it was being presented to the public as the merest down payment on what Americans owed.

The best evidence we have is that it was too much for most Americans from the beginning. The rhetoric that brought Reagan two landslides was, among other things, a sign that Americans were unwilling to bankroll with their taxes the civil rights and welfare revolution of the 1960s and the social change it brought in its train.

In retrospect, we can see that by acquiescing in the ouster of Richard Nixon after the previous landslide, those who voted for him had lost their chance to moderate the pace of that change. With the removal of Nixon, promoters of the Great Society had bought the time necessary to defend it against “backlash,” as democratic opposition to social change was coming to be called. In the near-decade that elapsed between Nixon and Reagan, entire subpopulations had become dependent on the Great Society. Those programs were now too big to fail.

They were gigantic. Once debt was used as a means to keep the social peace, it would quickly run into the trillions. One of Johnson’s lower-profile initiatives from 1965, the Higher Education Act, created the so-called Pell Grants to help “underprivileged” youth go to college. Their cost had risen to $7 billion by the time Reagan came to Washington. Although their effectiveness was disputed, there was an iron coalition of educational administrators and student advocates behind them. So Reagan didn’t touch them. They would swell to $39 billion by 2010. And they were not the whole story of federal support for education. According to one sympathetic account, federal grants and loans to college students, adjusted for inflation, were $800 million in 1963-64, $15 billion in 1973-74, and $157 billion in 2010-11.

Such grants didn’t just finance individual educations. They provided a pool of billions in investment capital that spawned new for-profit universities set up largely to collect them. In the 21st century, the largest collector of Pell Grant tuition would be the University of Phoenix, a nationwide open-enrollment “university” founded in 1976. Its students owed $35 billion in taxpayer-backed federal loans. Their default rate was higher than their graduation rate. More and more the vaunted Reaganite “private sector” was coming to operate this way. It was a catchment area set up to receive government funds—usually by someone well enough connected to know before the public did how and where government funds would be directed.

Reagan stinted on none of the resources required to construct Johnson’s new order. Having promised for years that he would undo affirmative action “with the stroke of a pen,” lop the payments that LBJ’s Great Society lavished on “welfare queens,” and abolish Jimmy Carter’s Department of Education, he discovered, once he became president, that to do any of those things would have struck at the very foundations of desegregation. So he didn’t—although Democrats and Republicans managed to agitate and inspire their voting and fundraising bases for decades by pretending he had. Meanwhile, his tax cuts provided a golden parachute for the white middle class, allowing it, for one deluded generation, to re-create with private resources a Potemkin version of the old order.

Those losing out had to be compensated. Consider affirmative action—unconstitutional under the traditional order, compulsory under the new—which exacted a steep price from white incumbents in the jobs they held, in the prospects of career advancement for their children, in their status as citizens. Such a program could be made palatable to white voters only if they could be offered compensating advantages. A government that was going to make an overwhelming majority of voters pay the cost of affirmative action had to keep unemployment low, home values rising, and living standards high.

Reaganomics was just a name for governing under a merciless contradiction that no one could admit was there: civil rights was important enough that people could not be asked to wait for it, but unpopular enough that people could not be asked to pay for it. Reagan permitted Americans to live under two social orders, two constitutional orders, at the same time. There was a pre-Great Society one and a post-Great Society one. Paying for both soon got expensive.

The cost can be measured roughly by the growth of the debt, public and private, over the decades after Reagan’s arrival in the White House. By 1989, the year Reagan left office, according to an estimate by the economist Roy H. Webb of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, the government’s unfunded liabilities (mostly for Social Security, Medicare, and veterans’ benefits) had reached $4-5 trillion, and would rise exponentially if nothing were done. Nothing was done. By the time of the 2016 election, a calculation of those liabilities similar to Webb’s ran to at least $135 trillion.

Ronald Reagan saved the Great Society in the same way that Franklin Roosevelt is credited by his admirers with having “saved capitalism.” That is, he tamed some of its very worst excesses and found the resources to protect his own angry voters from consequences they would otherwise have found intolerable. That is what the tax cuts were for.

Each of the two sides that emerged from the battles of the 1960s could comport itself as if it had won. There was no need to raise the taxes of a suburban entrepreneur in order to hire more civil rights enforcement officers at the Department of Education. There was no need to lease out oil-drilling rights in a national park in order to pay for an aircraft carrier. Failing to win a consensus for the revolutions of the 1960s, Washington instead bought off through tax cuts those who stood to lose from them. Americans would delude themselves for decades that there was something natural about this arrangement. It was an age of entitlement.

Periods of fiscal irresponsibility are often not immediately recognizable as such. Outwardly they can even look like golden ages of prosperity, because very large sums dedicated to investment are freed up for consumption. That is exactly what the standard Solow growth model and other economic descriptions of investment predict. Societies can even go through periods of extraordinary material and cultural radiance when they are on the verge of bankruptcy.

A writer can only marvel at the beauty and variety of electric typewriters that were available to the American public in the 1980s, just before word processing programs would doom them forever: Underwood, Smith Corona, Royal, Remington, Olivetti, and the IBM Selectric, elegant, immovable, authoritative. A reader can only marvel at the quality of newspapers available in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, before almost all newspapers gave way to ranting opinion websites. They were thick. The biggest New York Times ever, published on September 14, 1987, was 1,612 pages long and weighed 12 pounds. They were thorough, as filled with articles on everything from poetry to politics to philately to philandering as they had been throughout the 20th century, but by the turn of the 21st most of them were in color! Using resources taken from future generations, the Baby Boom generation was briefly able to offer the vision of an easy and indulgent lifestyle, convincing enough to draw vast numbers of people to construct it, like the pyramids or the medieval cathedrals or the railroads.

Immigration, Inequality, and Debt

Draw people it did. collectively, American Baby Boomers cashed out of the economy their forebears had built, shifting the costs of running it not just to different generations but to different parts of the world, through outsourcing and immigration. These, too, are a form of borrowing. Low-wage immigrants subsidize the rich countries they migrate to, and this is especially true of illegal immigrants. They are low-wage precisely because they are outside the legal system. Ultimately, natives pay some kind of “bill” for such labor. Either they invite the laborers into their society, and the costs to natives take the form of overburdened institutions, rapid cultural change, and diluted political power; or they exclude the laborers, and the costs take the form of exploitation, government repression, and bad conscience. Until that bill comes due, immigration must be counted among a country’s “off-balance-sheet liabilities.”

These liabilities are difficult to quantify. Mass immigration can help a confident, growing society undertake large projects—the settlement of the Great Plains, for instance, or the industrialization of America’s cities after the Civil War. But for a mature, settled society, mass immigration can be a poor choice, to the extent that it is a choice at all. Reagan was tasked by voters with undoing those post-1960s changes deemed unsustainable. Mass immigration was one of them, and it stands perhaps as his emblematic failure. Reagan flung open the gates to immigration while stirringly proclaiming a determination to slam them shut. Almost all of Reaganism was like that.

The Hart-Celler immigration reform of 1965 is sometimes overlooked amid the tidal wave of legislation that flowed through Congress that year. It overturned the “national origins” system, passed under the Immigration Act of 1924 and reaffirmed in 1952, that had aimed to keep the ethnic composition of the United States roughly what it was. Even in the mid-1960s, immigrants from Britain and Germany made up more than half of national “quota” immigration—and those countries plus Ireland, Italy, and Poland accounted for almost three quarters.

It is hard to say exactly what the bill’s backers believed they were doing. On one hand, they sang of an America that was triumphing over its historic racism. On the other, they promised even more ardently and solemnly that doing away with national-origin quotas would do nothing to change the American ethnic mix. “Quota immigration under the bill is likely to be more than 80% European,” said its House sponsor, Emanuel Celler.

Once the bill passed, Johnson summoned the Congress to a signing ceremony hundreds of miles away at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, an extravaganza at odds with his soft-pedaling of its importance. “This bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill,” he said. “It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives, or really add importantly to either our wealth or our power.”

He did protest too much. The Hart-Celler bill would alter the demography of the United States. It would also alter the country’s culture, committing the government to cut the link that had made Americans think of themselves for three centuries as, basically, a nation of transplanted Europeans.

“The American Nation returns to the finest of its traditions today,” Johnson said. “The days of unlimited immigration are past.” In fact, those days were past only because of the restrictive laws of 1924—which Johnson was now striking from the books. Johnson’s new attorney general, Nicholas Katzenbach, shared the president’s naïveté. Katzenbach had claimed, more likely from innumeracy than from any intent to deceive, that the new kind of migration would account for precisely “two one-hundredths of 1%” of future population growth. “Without injury or cost,” he proclaimed, “we can now infuse justice into our immigration policy.”

Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy, younger brother of the slain president, thought this way, too. In shepherding the Hart-Celler bill through the Senate, Kennedy had been just as reckless as Katzenbach and just as wrong as LBJ. “The ethnic mix of this country will not be upset,” he had said. He even named the nine countries that would be the principal beneficiaries of the new open system: China, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and Yugoslavia. (Of these, only China would figure among the top ten sources of immigrants half a century later.) “The bill will not aggravate unemployment, nor flood the labor market with foreigners, nor cause American citizens to lose their jobs,” he said. “These are myths of the first order.”

But Kennedy added something new to his appeal. Barely a year after his brother’s assassination, he cast the bill’s opponents as unpatriotic and un-American:

Responsible discussion is expected on the provisions of any bill. The charges I have mentioned are highly emotional, irrational, and with little foundation in fact. They are out of line with the obligations of responsible citizenship. They breed hate of our heritage, and fear of a vitality which helped to build America.

Like Katzenbach, who believed that justice could be secured “without injury or cost,” Kennedy had a hard time distinguishing between America’s morals and its interests. It is a confusion that puts one on the road to strife. If morals and interests always coincide, then the person who opposes your interests is probably evil. In Kennedy’s swagger we can see a harbinger of America’s 21st century political culture.

Immigration and the Failure of Democracy

Not only did every promise of the Hart-Celler bill’s sponsors wind up wrong. Even the warnings of the bill’s detractors—excitable pamphlet-pushers like the American Committee on Immigration Policies—underestimated the sea change it would bring. In the three-and-a-half centuries between its discovery and 1965, the United States had received 43 million newcomers (including a quarter-million slaves). In the half-century that followed Hart-Celler, it would get 59 million.

From that perspective, the migration problem that confronted Reagan early in his presidency was still relatively minor. An unintended consequence of the 1965 law was to favor disorderly over orderly immigration. Low-volume European migration had not required a vast rural and border enforcement apparatus, but by the mid-1970s a new kind of immigration was under way. Roughly 3 million illegal immigrants, most of them Latin American agricultural workers in the Southwest, were overburdening public services and making natives uncomfortable.

Even after the Reagan “revolution,” the political parties differed little on immigration. That is how Ted Kennedy, a driving force behind the Hart-Celler law, ended up playing a powerful role in Reagan’s attempts to fix it. In the waning days of the Carter Administration, Kennedy proposed a Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy, chose Notre Dame president Father Theodore Hesburgh to head it, and selected the reading materials that would guide it. Two of the Kennedy commission’s members, Republican Senator Alan Simpson of Wyoming and Democratic Congressman Romano Mazzoli of Kentucky, sponsored the legislation that would become the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA).

Simpson-Mazzoli aimed at a bold compromise. It legalized and offered American citizenship to illegal immigrants who could prove they had been resident in the United States for even the briefest of stays. A Special Agricultural Worker (SAW) program gave permanent residency to workers who could show they had done 60 days of farm work between May 1985 and May 1986, regardless of whether they knew any English or had any understanding of American civics. A quarter-million were estimated to be eligible for the program, but the documentation and testimonials it required were easily counterfeited: 1.3 million wound up using it. Those admitted came to well over 3 million in total.

To keep this easy mass legalization from incentivizing future immigration, the bill proposed shutting down illegal immigration almost entirely. It contained documentation requirements, $123 million in new security funding, and ferocious-looking penalties for businessmen who knowingly hired illegals. Simpson-Mazzoli brought with it the single largest expansion of federal regulatory power since the establishment of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 1970.

There was something disquieting about this level of intrusion into the decisions of business owners, even if it had precedents in the New Deal’s National Recovery Administration and in the Civil Rights Act, particularly in affirmative action, which had by then been up and running for more than a decade. That turned out to be the core of the problem. The parts of the law that encouraged immigration—the amnesty, the processing of working papers—were unpopular, but their introduction went smoothly. They were real. The parts that retarded immigration—the border controls, the employer sanctions—were popular, but they proved impossible to enforce. They were fake.

Opponents of mass immigration were inclined to see IRCA as an outright fraud perpetrated on the public. The truth was more complicated. It had to do with a change in the country’s constitutional culture.

The Changing Spirit of Civil Rights

To do away with illegal immigration, Americans would have had to send a strong message, not just in their statutes but in their enforcement practices and their day-to-day behavior, to the effect that illegal immigration, and therefore illegal immigrants, were not welcome. Every poll from the time tells us that Americans intended to convey just such a message. In June 1986, those who wanted less immigration outnumbered those who wanted more of it by 7 to 1 (49 to 7%). Historically, whenever social change began to move too fast, this kind of gruff, coarse, reactionary plurality would “come out of the woodwork.”

Doris Meissner, later the commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, said of the migrants who were in the country illegally, “Everyone assumed they would just leave, that the new employer restrictions would push them out.” That approach to overheated immigration might have worked in a pre-1964 America, but the country had changed. Now there was no woodwork.

Immigration was one of many subjects that were becoming harder to discuss openly. As late as 1975, the Los Angeles Times could still report on economic competition from immigrants, headlining a story “Employers Prefer Workers Who Can Be Exploited, Paid Minuscule Wages, U.S. Officials Say.” That year, 47% of news stories about immigration mentioned its dampening effect on wages. By the turn of the century, only 8% did. In 1976, the Texas Democrat Ann Richards reportedly said, in the course of a campaign for the Travis County commissioners court, “If it takes a man to hire non-union labor, cross picket lines, and work wetbacks then I say thank God for a woman or anyone else who is willing to take over.” It was a sentiment that most Texas liberals of the time would have been proud to avow. By 1990, when Richards made a successful run for governor, “wetback” was an inadmissible slur and the report of the old speech jeopardized her campaign.

In late amendments, the 1986 IRCA bill was filled with language stressing that an employer could be held liable for discriminating on account of national origin. This looked like window dressing, but in the new, post–Civil Rights Act judicial climate, it became the heart of the bill. It turned inside-out the penalties against employers for hiring illegal immigrants. However harsh the “employer sanctions” had originally looked on paper, they required employers to act in ways that civil rights law forbade. An American boss now had more to fear from obeying the immigration law than from flouting it. An INS official sent in 1987 to investigate a factory on Long Island suspected of using illegal labor stressed that he was there “to explain the new immigration law’s provisions on employer sanctions, ‘not enforce them.’” As housing secretary three years later, Jack Kemp sought a waiver that would permit the city of Costa Mesa, California, to offer welfare benefits to the newly arrived, circumventing a legal ban.

In policy terms IRCA is usually described as a mix of successes and failures. In constitutional terms it was a calamity. Presented as a means of getting immigration under control, IRCA wound up mixing explicit incentives to immigrate (via amnesty) with implicit ones (via anti-discrimination law). It provided courts and federal civil rights agencies—both of them staffed with law school graduates and other highly credentialed professionals at the very apex of the American social pyramid—with new grounds for overruling and overriding legislatures and voters on any question that could be cast as a matter of discrimination. That was coming to mean all questions. Every law was turning into an expansion of civil rights law.

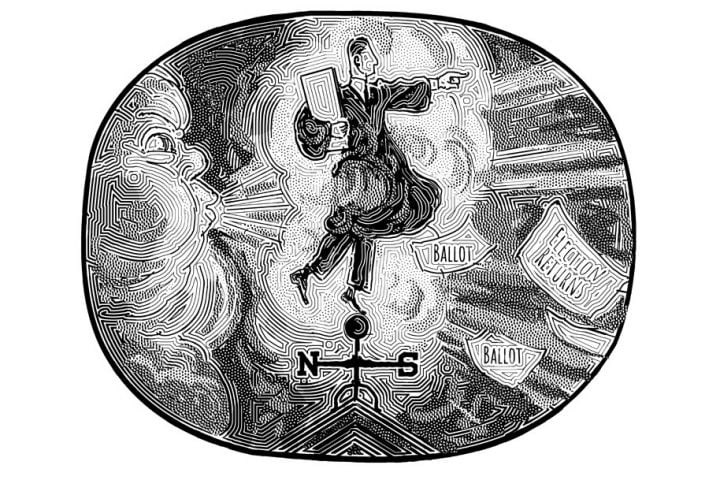

In a 1994 referendum, 5 million Californians sought to deny welfare benefits to illegal immigrants, giving the state’s Proposition 187 an 18-point landslide at the polls. But district court judge Mariana Pfaelzer decided they were wrong—on the grounds that limiting state welfare payments amounted to setting immigration policy, which was a prerogative not of the states but of the federal government. And that did it for Prop 187.

The wave of immigrants interacted with the country’s changing legal regime in a way that would make this migration different from the last. Even when it was working best, immigration introduced tensions into the system being built up around civil rights. For one, the success of new immigrants, Harvard sociologist Nathan Glazer noted, provoked “unspoken (and sometimes spoken) criticism” of blacks for their relative slowness to rise. For another, the new migrants were being shepherded into the civil rights system as potential victims of discrimination, not as potential perpetrators of it. Illegal immigrants were attractive to employers because they had fewer rights in the workplace. They were unattractive to the general public because they had more rights in the courtroom.

The rags-to-riches stories of people from the most desperate corners of Asia were similar to those of early immigrant groups. Those stories, often repeated and widely publicized, reunited Americans with the pride they felt in the European melting pot of the early 20th century. In 1983, four years after she had arrived in the United States speaking no English, the Cambodian refugee Linn Yann, whose father had been killed by the Khmer Rouge, won the Zone V spelling bee in Chattanooga, getting “exhilarate” and “rambunctious” right and losing the Chattanooga–Hamilton County finals only when given a word she had not come across in Tennessee: “enchilada.”