Not so long ago, American conservatives seemed to be converting the world to their ideas. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, country after country abandoned socialism for free markets, embracing such Reaganite themes as incentives, individualism, and responsibility. It looked as though the sun would never set on the friends of American conservatism. Yet today, American conservatives have never felt so alone.

This is not a matter of how many people around the world like American conservatives, but of how many are like them. To be sure, many political movements don’t have counterparts in other countries. But Europe and America are politically kin, and when in the 1980s Ronald Reagan took his stands for markets and against the Soviets he found ready and stalwart allies in Margaret Thatcher, Helmut Kohl, and other indigenous conservatives. Yet all we hear of these days is the “exceptionalism of modern American conservatism.” What happened to Europe?

Finding an answer begins with a comparison of contemporary American and European conservatives, especially concerning their basic assumptions—or operating principles—about economics, foreign policy, crime, and morality.

Market vs. State

American conservatives believe that a healthy modern economy is so complex and innovative that most economic decisions have to take place in the private sector, where scattered information is located, and risk may be rewarded or punished. Government is best at enforcing rules of the game and engaging in limited redistribution. When it does much more than that, it creates inefficient regulations and bureaucracies prone to expanding rather than learning.

This basic assumption runs deep in American life, not merely because we’ve spent too much time in post office lines—everyone on earth has done that—but because we’re in a position to compare the post office to responsive, dynamic private businesses of all kinds. Many Europeans think similarly, especially business leaders, free-market activists, policy wonks, center-right politicians (including, apparently, the German Christian Democrats’ Angela Merkel), and the occasional center-left leader such as Tony Blair or Gerhard Schroeder.

But most Western Europeans fear that markets will fail to meet their needs and satisfy their interests. They maintain a faute de mieux faith that government is the indispensable actor in economic life. Even when compelled by economic crisis to trim taxes, privatize, and curb spending—that is, even while recognizing implicitly that these measures attract investment and encourage growth—European leaders rarely offer principled criticism of government intervention, much less positive rhetoric about the marketplace. (Jacques Chirac’s center-right cabinet is now privatizing state entities, not because private ownership is more efficient but primarily to cut the deficit and pay down the debt.) The European Union’s proclaimed drive to become internationally competitive is top-down and government-centered. Not surprisingly, “Thatcherite” and “neo-liberal” continue to be labels insultingly applied and hotly denied. All this is true even for several right-wing “populist” parties, such as France’s National Front, which calls occasionally for tax limitation but more often emphasizes protectionism and a welfare state generous to native-born Frenchmen.

These views have not been dislodged, even by serious economic problems. And Europe’s economic problems are serious. The unemployment rate is stuck at around 10% in Germany and France, and if anything this underestimates the true figure—even more unemployment is concealed through extensive job-training and early-retirement schemes. The fact that many continental European economies have such mechanisms for sidelining less-skilled workers makes it all the more striking that labor productivity still generally grows faster in the United States. For decades, France and Germany had narrowed the gap in labor productivity with the U.S., but in the past 15 years their progress slowed and then reversed.

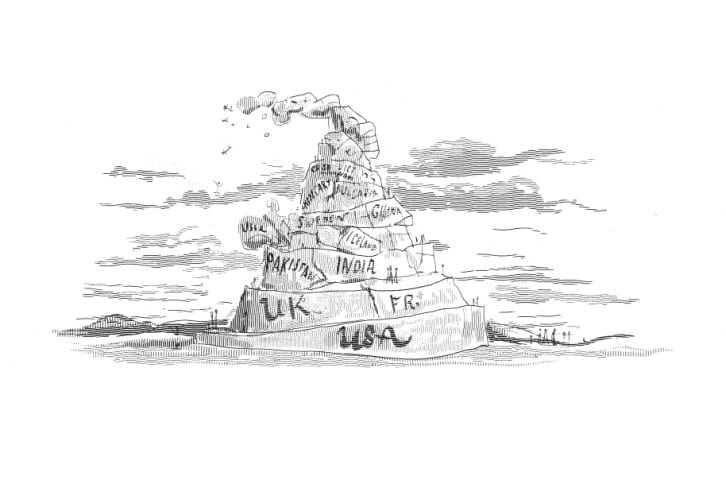

The result is that average U.S. per capita income is now about 55% higher than the average of the European Union’s core 15 countries (it expanded to 25 in 2004). In fact, the biggest E.U. countries have per capita incomes comparable to America’s poorest states. A recent study by two Swedish economists found that if the United Kingdom, France, or Italy suddenly were admitted to the American union, any one of them would rank as the 5th poorest of the 50 states, ahead only of West Virginia, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Montana. Ireland, the second richest E.U. country, would be the 13th poorest state; Sweden the 6th poorest. The study found that 40% of all Swedish households would classify as low-income by American standards.

Predators

A comparable divide in operating assumptions exists on foreign policy. By and large, American conservatives believe that although international conflicts may arise from uncertainty, misunderstanding, and mutual threats, they usually result from simple predation, power-hunger, and hatred. Global cooperation is possible when would-be predators are deterred, which requires muscular firmness. Democracies are uniquely suited to be enforcers of international order because they are least likely to be its transgressors—which is the reason Americans have traditionally championed an integrated and assertive Europe, instead of seeing it as a threat.

Some Europeans share this view, including most British and many Dutch and Danish conservatives, as well as Blair and other Laborites. Once upon a time, the Gaullists thought like this, and José María Aznar and other Spanish conservatives do so still. But most European governments now practice what Americans would recognize as a liberal foreign policy. This is not so much because Europeans inhabit what Robert Kagan calls a “post-historical paradise of peace and relative prosperity.” Instead they insist on seeing misperception, insecurity, and pride as the root of most international conflicts, which accordingly are best defused by reassurance and the careful avoidance of confrontation, ultimatums, and threats. The Spanish government’s response to the Madrid bombings—hasty withdrawal from Iraq—was denounced as appeasement by most Americans, but not by most Europeans. Of course, the British response to the London bombings has been quite different, at least so far.

American conservatives believe that the deterrent approach toward international predators should be firmly applied to would-be domestic predators as well. One might expect the same sensibility in Europe, given high crime rates there. Despite enduring stereotypes to the contrary, Europeans now match or surpass America in most crimes, including violent ones (except murder and, to a lesser degree, rape). In per capita terms, Belgium has more assaults than the U.S., the Netherlands nearly the same number, and France is rising fast. England and Wales have more robberies, the Dutch almost as many, and England and Denmark beat America in per capita burglaries and (here joined by the French) in theft and auto theft. After lecturing Americans that expensive welfare states would ensure social peace, many Europeans now find themselves saddled with both high welfare costs and high crime, while American crime rates have dropped. Western Europeans have met high crime rates with policing and prisons, of course, but more notably with multicultural appeals, jobs programs, and policies aimed at “social insertion” of the alienated. As Theodore Dalrymple explains, such policies transmit the message that criminals are victims, too, and their actions understandable responses to trying circumstances. The result, as in foreign policy, is a lack of resolve among the virtuous, wink-and-nod cynicism among offenders, and excuse-making by everyone.

Hard and Soft

European stereotypes hold that American conservatives, under increasing evangelical influence, want morality to be systematically legislated. Actually, American evangelicals spend far more time shaping behavior in the private or civil sphere than through government. They teach personal values like family responsibility, clean living, self-discipline, voluntarism, and moral clarity in the face of wrongdoing. This ambitious project of private-sector character shaping is virtually without counterpart among purely secular Americans. And it is almost nonexistent in Europe, at least beyond the state-sponsored project of inculcating anti-racism, multiculturalism, and laicism as among the highest virtues.

In sum, American conservatives of nearly every stripe agree that the world is a complex and competitive place in which human nature and its limitations play pervasive roles. In such a world, good people are wise to cultivate individual skills and character traits, to limit centralizing power (especially government), to confront rather than duck serious challenges, and to get incentives right, especially for predators, with an eye toward encouraging virtue, and at least restraint.

Different terms have been invoked to distinguish these conservative operating assumptions from their main alternatives. Television personality Chris Matthews is sometimes credited with the notion that Republicans and Democrats are, respectively, the “daddy” and “mommy” parties. Daddy tries to toughen citizens to cope with life’s ordeals, while mommy tries to shield them from its harshness. U.C. Berkeley linguistics professor (and Democratic consultant) George Lakoff tweaks this to say that conservatives advocate the “strict father” model for America while progressives are “nurturant parents.” The discerning journalist Michael Barone distinguishes between “hard” and “soft” America, representing, respectively, contemporary conservatism and liberalism.

Whatever terms we use to describe the right-wing worldview, American conservatives often develop a sense of “tribal” identification with those who share it, which explains their special bond with many Australian and British conservatives, and even with Tony Blair. This also explains recent conservative interest in Germany’s Angela Merkel, who seems to understand economic incentives, and France’s Nicolas Sarkozy, who stands out for his toughness on crime, praise for bourgeois virtues like hard work, and emphasis on adapting France’s political economy to a competitive world. The problem is that while American conservatives share one of their operating principles with some Europeans and another principle with some others, they don’t share the whole bundle with very many at all. To use Barone’s terms, most Americans have hard values while the majority of West Europeans have soft ones.

The Churning State

Why have America and Europe diverged so much in their beliefs? Consider two groupings in society: communities of religious faith and sectors that are economically independent of government. Together these form the building blocks of American electoral conservatism, and are the two main generators of daddy party beliefs in America. Both are greatly diminished in Europe.

Barone argues that hard values are inculcated by competition while soft ones are promoted and preserved by “coddling.” Adult life in Europe, he suggests, is softened by protectionism, welfarism, and other public subsidies. Despite some variation, three broad economic patterns stand out in Europe. In the first place, proportionately fewer people work. To cut unemployment lines, many of their citizens are encouraged to retire early, on pensions far more publicly-funded than ours. The stand-out cases are France and Germany, Europe’s two largest economies, with labor force participation rates 10 to 15 percentage points lower than America’s (about 55% in France; over 70% in the U.S.). Second, a larger share of the European workforce is employed by government. Third, Europeans receive more income and benefits from welfare programs in the form of health care, housing, and income support. These benefits reach deep into the middle class.

The result is a noticeably larger share of the population directly dependent on government benefits and services, and therefore directly threatened by any retrenchment of these in favor of private enterprise and private social provisioning. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Buchanan applies the label “churning state” to a welfare state in which cross-subsidies are so extensive and interwoven that virtually everyone is a beneficiary and no one will be the first to surrender his subsidy. And the recipients are often right to be afraid. For example, the unemployed would be foolish to give up generous benefits when for more than a decade their economies have been unable to produce enough new jobs.

Now add the influence of religion. The more religious an American is, the more likely he or she is to vote conservative. Millions of “people of faith” are drawn to, and have their values reinforced by, America’s vast and well-integrated religious apparatus of sermons, radio stations, television shows, books, stores, and mega-churches, an apparatus that shapes their beliefs about self-discipline, human nature, evil-doing, and much else.

By contrast, during the past century Europe experienced a drastic decline in rates of religious practice and faith. Whereas some 45% of Americans say they attend weekly religious services, one study in 1990 found comparable rates as low as 19% in western Germany, 13% in Britain, and 10% in France, and these have almost certainly fallen since then. There is no comparable apparatus of evangelization. As the sociologist of religion Peter Berger notes, this makes Western Europe stand out: instead of America being conspicuously religious by global standards, Europe is conspicuously secular.

The Median Voter

Such transatlantic differences can be highly consequential politically. Within a nation, major parties generally craft their platforms and rhetoric to attract the “median voter,” that is, the hypothetical voter at the exact center of the political spectrum, whose swing can determine the election. In most European countries, the median voter is both less religious and more dependent on government than the median voter in the United States. This tugs American politics to the right and European politics to the left.

This makes political differences appear even starker than the sociological ones. For example, American liberals when shaping their election platforms have little choice but to sideline “progressive” catchphrases, and instead proclaim their commitment to individual responsibility, the private sector, and toughness on crime and national security. This centrist posturing, especially by Democratic presidential candidates, is so thorough that non-Americans are often unaware that there is a sizable left-liberal minority in the United States. Democrats steer clear of any suggestion that they want to make America more like, say, Europe.

The opposite happens in Europe. Center-right politicians in Germany, France, Spain, Sweden, and elsewhere compete for a very different kind of median voter, leaving them little choice but to defend the welfare state, strict secularism, and a soothing foreign policy (by avoiding talk of toughness at home or abroad). Germany’s Christian Democrats, for instance, often compete with the Social Democrats to raise public pensions. European business leaders who understand supply-side incentives, job creation, and taxes and regulation more or less as American conservatives do, censor themselves in order to remain politically relevant. Here, too, the effects can be so thoroughgoing as to obscure the fact that there is a sizable minority of American-style conservatives in every European country. And European conservatives reinforce this misperception by avoiding any suggestion that they want to make their countries more like America.

This explains why so many conservative projects in Europe have rested on the thin reed of individual leaders. Even Margaret Thatcher—who was lucky enough to govern in the face of a divided opposition and in the wake of the 1970s’ economic crisis—still felt compelled to endorse a health care system more socialized than many American liberals would favor. State spending began to rise again soon after she was succeeded by fellow Conservative John Major. Helmut Kohl left even less of a market reform legacy. So it’s no surprise that the years since the fall of the Berlin Wall have witnessed a great deal of homeopathic cures for, but no serious surgery on, the European welfare state. This is especially striking in a country like France, which has suffered high (8-12%) unemployment for nearly 25 straight years. The record suggests that it is imprudent to invest much hope in rising center-right politicians like Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy, however individually promising they appear.

Euro Elite

The perception that Europe is uniformly center-to-center-left is further reinforced by the fact that public expression is monopolized by a collusive journalistic, intellectual, and Eurocratic elite whose “arrogance [is] almost beyond belief,” in the words of William Kristol. Its ideologically lopsided political and intellectual elite is so potent that it may shape Europe’s political identity as much as secularism and economic dependence do. Mainstream European press coverage of America, free markets, and robust conservatism is so routinely paranoid and hyperbolic that it makes Howard Dean look temperate.

This can conceal important divergences between elites and average citizens. The June 2005 Dutch referendum on the E.U. constitution revealed a profound disconnect between the parliamentary and journalistic classes, on the one hand, who overwhelmingly favored the treaty, and average citizens on the other, who rejected it 62% to 38%. Without the public vote, negative opinion polls would have been explained away by the elite as revealing little more than a shallow, momentary fit of temper. A lot may be obscured by the fact that 15 of the 25 E.U. governments haven’t planned even consultative referendums for adopting the new constitution.

Kristol has suggested that, in a way, Europe is stuck politically in America’s 1990s, with a cultural and political elite plagued by drift, failure, and scandal—but without the breakthrough achieved here by reform-minded conservatives like Rudy Giuliani and Newt Gingrich. Yet intellectually, Western Europe seems even further behind than just the 1990s. Many Europeans still find it logical to respond to unemployment with protectionism and government jobs programs; leaders routinely speak of corporatist-style “social dialogue” between the state and major interests; a center-right prime minister argues that subsidized agriculture is central to France’s economic dynamism; few expect Europeans to act resolutely to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons; and governments try to stem globalization with what one scholar calls a “social democratic Maginot Line.”

All this reminds one of nothing so much as the 1970s. The spirit of Jimmy Carter exited the American political stage decades ago, but, like Jerry Lewis, it remains a matinee favorite on the other side of the Atlantic.

Common Cause

The bad news is that real change is going to happen not by cashiering leaders or nudging political parties, but by changing what the voters think and want. And that is long, hard work. The good news is that the ranks of robust conservatives may be expanding in Europe and elsewhere. In Australia and Japan, security threats and the accumulation of market-oriented economic reforms seem to be bringing center-right sectors around to postures that American conservatives can recognize and appreciate. In Great Britain, Thatcher’s mission of de-socializing the Labor party has borne fruit. (It is true that government spending has risen under Labor, but it has under the Bush Administration, too).

In Western Europe as a whole, prospects for a “values” revival remain hazy. But another change might help generate daddy-party beliefs: further economic liberalization, which would not only improve the region’s economy (cutting unemployment, for example) but, by creating more competitive markets, might spread hard values, at least concerning business. How could liberalization be promoted? Much economic reform is held back by Europeans’ fears of the economic unknown, specifically that markets cannot provide at reasonable cost the services and insurance coverage that their governments currently offer (in return for high taxes).

Two mechanisms might erode those fears: first, the potentially powerful demonstration effect of the former Communist countries’ success. Today, a contest is underway between economic liberty in east-central Europe—whose growth could demonstrate the efficiency of their less regulated and less taxed economies—and the efforts of the French, German, and other Western European governments to force growth-stifling “harmonizing” measures on the new E.U. members. East-central Europe can only play an instructive role if its economies remain free. American conservatives thus have an interest in maintaining the perceived viability of the market-oriented central European “social model.” To this end, the U.S. could offer those countries closer trade ties and moral-diplomatic support in their attempt to stand up to Brussels (and Paris, and Berlin, and…).

A second means of eroding anti-market skepticism would be a campaign of public diplomacy, not by the U.S. government but by the American conservative movement. Such a campaign would show Western Europeans that a great deal of their fears are unfounded. Books like Cowboy Capitalism (2004), by Olaf Gersemann, a German business journalist, have begun to debunk myths about America’s poverty, joblessness, social immobility, and quality of life; but more efforts are needed. Blogs remain an undeveloped medium in Europe and might help kickstart the resistance to the European Left’s intellectual hegemony. A little encouragement might go a long way.

It is not only American conservatives who have an interest in making the world safe for conservative principles. The story of contemporary American conservatism is in many ways the story of modern America itself. American liberals think they see their own counterparts all over the world, but they have ample reason to feel alone, too. As John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge note in The Right Nation (2004; see Kenneth Minogue, “Exceptionally Conservative,” CRB, Summer 2005), “the more you look at [America’s] prominent Democrats from an international perspective, the less left-wing they seem.” “For the foreseeable future,” they write, “the Democrats will be a relatively conservative party by European standards.” It may be that our liberals and conservatives have more in common than they realize, and thus much to gain by seeing their common principles prosper around the world.