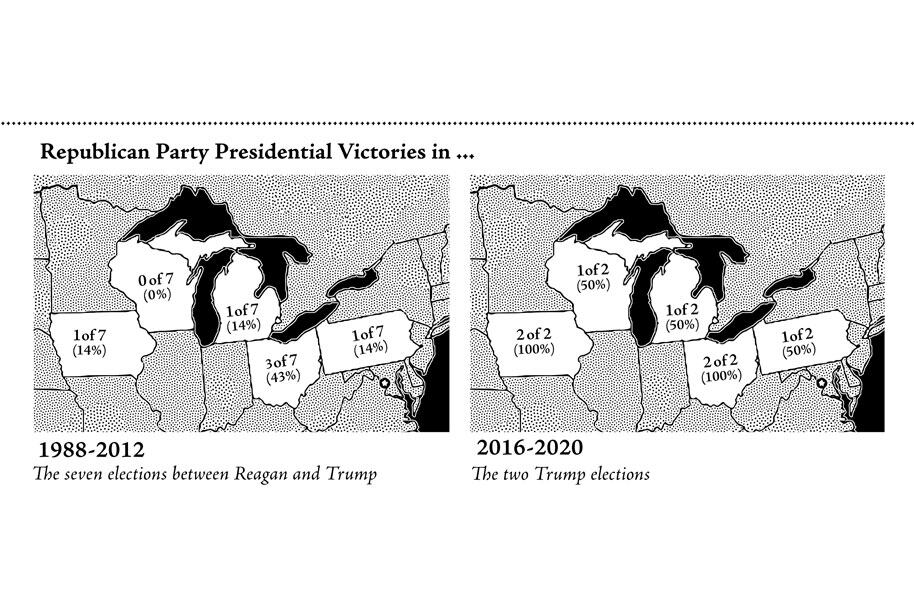

Just nine months in, the Biden administration has already shown that it combines the ideological ambitions of the Wilson, Roosevelt, Johnson, and Obama Administrations with the incompetence of Jimmy Carter’s. So it’s never too early to start thinking about 2024. Before Republicans begin to contemplate the next slugfest, however, they would do well to take stock of developments over the past three presidential elections and the ways in which the electoral map has changed as a result. The salient fact is that Donald Trump won more Midwestern swing states over the span of two elections than Republicans had won over the prior seven presidential elections combined, dating back to 1988. This is evidence of a budding Main Street coalition. But it remains to be seen whether Republicans will nurture and cultivate that coalition or let it die on the vine, a reminder of an unconventional president whom many establishment Republicans would sooner forget.

After Mitt Romney lost to Barack Obama in 2012, the Republican National Committee (RNC), not generally known for its forays into forensic medicine, performed an “autopsy.” Romney had lost all five Midwestern swing states—Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa—along with six other swing states: Florida, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Colorado, New Hampshire, and Nevada. Almost worse, the closest he had come to victory in any of those states, aside from Florida, was three percentage points. The RNC autopsy concluded that Romney’s defeat resulted not from his inability to prosecute the case against Obamacare (shortly after the election, he declared “Obamacare was very attractive”), not from his inexplicable choice to go into a “prevent defense” after his fine performance in the first debate, and not even from his having looked to many voters like the big-city multi-millionaire who buys the local mill in order to sell it for its parts and ship the jobs overseas. No, the autopsy concluded, Romney had been the helpless victim of an overpowering demographic wave. The solution was not to advance a Main Street agenda that appeals to Americans of all stripes, but rather to try to appeal to subgroups of Americans with specific policies, starting with open-borders immigration “reform.” This was the only way, according to the RNC, to surmount the fabled “Big Blue Wall,” which was allegedly formidable enough to keep a Republican nominee from winning the presidency even if that nominee were narrowly able to win the popular vote.

Four years later, after Senator Jeff Sessions had successfully led the effort to block the bipartisan Gang of Eight’s “comprehensive” immigration legislation, Republican voters mutinied against the GOP establishment that had produced both the autopsy and that bill. With 17 choices available, many with impressive credentials, GOP voters picked as their nominee someone who hadn’t so much as been the mayor of a small town. Donald Trump ran as an immigration hawk and a free-trade skeptic, and those and other Main Street issues carried him not only to the nomination but to the presidency. Exit polling from the National Election Pool, a network consortium comprising CBS, ABC, NBC, and CNN, found that among the 13% of voters who thought that immigration was the most important issue in the 2016 campaign, Trump beat Hillary Clinton by 31 percentage points (64% to 33%). Among the plurality (42%) who said that international trade “takes away U.S. jobs,” Trump won 64% to 32%. Overall, he won 6 of the 11 swing states that Romney had lost, scaling the “Big Blue Wall” without even winning the popular vote.

Winning on the Issues

In 2020, the combination of Trump’s personality and the novel coronavirus did him in. He lost despite exit polling showing that, among the plurality of voters (35%) who said the economy was the most important factor in their vote, five out of six (83%) backed him over Joe Biden. What’s more, the 11% of voters who said that crime and safety was their number one issue supported Trump by 44 percentage points (71% to 27%). Trump, however, never gave the serious yet hopeful addresses that Franklin Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, or Ronald Reagan would have relished giving during the COVID crisis, and therefore Americans never had a clear sense of where things were headed or why. Despite Trump’s impressive efforts to help spur the development of a vaccine in record time, among the one sixth (17%) of voters who said the coronavirus was their biggest issue, Joe Biden beat Trump, 81% to 15%. (Trump lost even worse—92% to 7%—among the 20% of voters who listed “racial inequality” as their top issue, but in more than two thirds of swing states, the coronavirus beat out “racial inequality” on the list of biggest concerns.) Trump didn’t play up immigration or trade enough in 2020 to motivate those doing the exit polling to ask specific questions about those issues.

In separate exit polling conducted by Fox News and the Associated Press, 61% of all voters in 2020 said Trump was not honest and trustworthy. But perhaps the best evidence of how tired voters were of Trump’s unorthodox way of comporting himself in the White House is provided by how poorly they thought of Biden, even as a majority cast votes for him. In the Fox News/A.P. polling, only 6% said they always agreed with Biden’s positions on important issues, while 33% said they never agreed with him on important issues; only 53% said he was healthy enough to serve effectively as president, and only 52% said he had the mental capacity to do so; just 39% said he was better able to handle the economy than Trump was; only half (50%) said he was honest and trustworthy, and less than half (48%) said he was a strong leader. It appears that, as in 2016, the issues largely favored Trump, but this time he lost the election to a weak opponent on the basis of the more intangible qualities of personality and leadership style.

That said, Trump did remarkably well in many bellwether counties and in several states that usually swing the election—such as Florida, Ohio, and Iowa, each of which he won convincingly—yet he lost because he did poorly among relatively affluent suburbanites in places like Arizona, Georgia, and the Philadelphia suburbs. One remarkable aspect of Trump’s rise and fall, therefore, is that voters in places that usually decide elections—presumably the most prized targets in any campaign—seem largely to have been won over to his Main Street agenda: strong at the border, skeptical toward “one world nation” trade policy, tough on crime, circumspect about foreign engagements, and committed to defending the traditional American way of life.

The fact that he lost his re-election bid anyway points to four major possibilities for 2024 and the future:

- The first is that the next Republican presidential nominee could shift away from this Main Street agenda, thereby forfeiting the inroads Trump made with these swing voters, while attempting to reclaim the affluent suburbs and restore the old party-affiliation map.

- A second possibility is that the next Republican nominee could run on the Trump agenda, minus Trump, but be defeated—either by losing the bellwether voter (because that voter turns out to have been more attracted to Trump than to his policies), or else by failing to regain the support of enough of the affluent suburbs, because such suburbanites have learned to love progressive and even woke policies.

- A third possibility—more likely, it would seem—is that a Republican running in the Trump policy lane, but not being Trump, could keep together most of this new Main Street coalition, and perhaps even expand upon it, while reclaiming many affluent suburbanites who were turned off mostly by Trump rather than by his policies. Such a nominee would test whether Democrats can really win future elections as the party of the affluent and the dependent but not of the everyday American.

- A fourth possibility is that Trump himself could run again at the age of 77, hope that GOP voters will focus on his first 46 months in office rather than his last two, and again become the party’s nominee. Voters in the general election, recalling the prosperous but tumultuous Trump years and the reporting on the Capitol Hill riot, would then have to decide whether to reward Trump with another term. It is anyone’s guess whether he will run again or how his potential candidacy would play out. Either way, Trump has provided the GOP with a blueprint for the future.

Bellwether Backing

Nationwide exit polling by the network consortium shows that in 2020 Trump improved upon Romney’s 2012 margins by 11 points among Hispanic voters (from down 44 points to down 33 points), and by 12 points among black voters (from down 87 points to down 75 points). Trump beat Romney’s margins by even more among black men (16 points better than Romney) and Hispanic women (14 points better than Romney). For that matter, in their respective re-election campaigns, Trump’s margin among black voters in 2020 (down 75 points) was slightly better than George W. Bush’s in 2004 (down 77 points), despite Trump’s having fared seven points worse with the electorate as a whole (down 4.5 points versus up 2.5 points). Such evidence makes it hard to dismiss Trump’s success in bellwether counties, as statistician Nate Silver’s website FiveThirtyEight does, as being mostly attributable to those counties being “much whiter and less college-educated than the country as a whole.”

Much has been made of the fact that Trump won 18 of the 19 bellwether counties in 2020 that had always voted with the national winner across the ten elections from 1980 to 2016. This stat is true but is less revealing than is often suggested. A more telling review of Trump’s performance in bellwether counties would rewind the clock to 2016. Prior to that election, there were 35 counties that had backed the national winner in every election from 1980 to 2012. In 2016, Trump won only 19 of these 35, breaking the streaks of 46% of them. The 18 that he won again in 2020, therefore, were somewhat self-selecting; they had already backed Trump once while many other bellwether counties hadn’t.

Still, the fact that Trump won all but one of these bellwether counties again, despite losing nationally, is impressive. Also impressive is that he won back two of the bellwether counties that he’d lost in 2016. The nature of those two reclaimed counties is revealing. One, Alamosa County, in south-central Colorado, is nearly half (48%) Hispanic. The other, Val Verde County in Texas, is on the Mexican border and went from backing Hillary Clinton by 8 points in 2016 to backing Trump by 10 points in 2020—an 18-point swing. Val Verde County is 82% Hispanic.

Overall, of the 35 bellwether counties that had perfect records in mirroring the nation from 1980 to 2012, Trump won 57% in 2020 while Biden won just 43%. What’s more, Trump beat Biden by double digits in 12 of these counties (and by more than 9.5 points in three more of them), while Biden won only seven by double digits, with each of Biden’s wins coming in counties with mostly suburban populations. But while Trump was winning most of these bellwether counties, often handily, Biden did dominate in another respect: he swept the ten counties nationwide with the highest median incomes—all but two of which are within striking distance of Washington, D.C. or Silicon Valley—by an average margin of 70% to 28%. It remains to be seen whether a campaign so attuned to elitist sensibilities offers a blueprint for future Democratic success.

In relation to the previous electoral map, the new map following the 2020 census is slightly more favorable for Republicans. Under the new map, a Republican nominee who wins all of the Republican-leaning swing states (Florida, Ohio, North Carolina, Georgia, and Arizona) must still do one of the following to achieve 270 electoral votes: 1) win Colorado, plus either Nevada or New Hampshire; 2) win Virginia, plus either Nevada, New Hampshire, or the congressional districts around Omaha, Nebraska, and in upstate Maine; or 3) win at least one swing state, in addition to Ohio, in the Great Lakes or Midwest region. In other words, if Republicans don’t think they can win in Virginia (despite Glenn Youngkin’s recent reminder that it remains a swing state) or Colorado—where they haven’t come within three points of victory in any of the past four presidential elections, and where ever-growing legions of federal lobbyists and marijuana enthusiasts don’t suggest favorable trends for the GOP—then they will have to win in Big Ten country, and not just in the Buckeye and Hoosier states. Specifically, they will need to win one of the region’s biggest prizes (Pennsylvania or Michigan), two of its smaller prizes (Wisconsin, Minnesota, or Iowa), or one of its smaller prizes plus Nevada or New Hampshire (or perhaps both Nevada and New Hampshire, if the smaller prize were Iowa). The party’s future presidential prospects, therefore, presumably hinge on how well it can perform in states bordering the Great Lakes or the upper Mississippi River.

Swing States Swinging Right

In Big Ten country Trump’s performance was remarkable. He made winning Iowa look easy, but it isn’t. No Republican in the prior seven presidential elections had won that quintessential swing state by even a full percentage point until Trump won it by more than eight—twice. Ohio had been within five points of the nation every year from 1964 to 2012, until it was more than ten points to the right of the nation twice under Trump. The last time a Republican presidential contender had fared better in Michigan than nationwide was when George H.W. Bush had done so at the end of the Reagan Administration in 1988, until Trump did so both in 2016 (when he won Michigan) and in 2020 (when he lost it by less than he lost nationally). In Wisconsin, Trump (in 2016) became the first Republican to win since Ronald Reagan. Not even Reagan ever won Minnesota—no Republican has since Nixon in 1972, the longest current Democratic streak among the 50 states—but Trump lost it by just 1.5 percentage points in 2016, the first time the state had been to the right of the nation since Dwight Eisenhower first ran in 1952. Finally, and most importantly, the last time Pennsylvania had been to the right of the national presidential vote was when its voters backed Thomas Dewey over Harry Truman in 1948, until it was to the right of the nation both in 2016 and 2020. These striking results are indicative of the appeal of a Main Street agenda across this crucial and likely decisive region.

Trump also did quite well in Florida. That state, the nation’s largest swing state and a must-win state for the GOP, has been to the right of the nation in every election since Jimmy Carter won it in 1976, but it was more to the right of the nation when Trump won it in 2020 than it had been in any year since 1988. (Texas, meanwhile, is not a swing state, and the prospect of winning it remains a Democratic fantasy, except in the context of a national landslide or perhaps a home-state candidate. The Lone Star State has been at least 10 points to the right of the nation in seven consecutive presidential contests.)

Trump fell short in 2020 because he didn’t pull as many of the Great Lakes states into his column as in 2016, because he couldn’t quite pull out Nevada (losing it by 2.4 points, just as in 2016), because he wasn’t competitive in Virginia, Colorado, or New Hampshire (losing each by at least seven points, after having been within 0.4 points in New Hampshire in 2016), and because he fell a sliver short in Arizona (by 0.3 points) and in Georgia (by 0.2 points), at least officially.

Georgia and Arizona were, nevertheless, more than four points to the right of the nation in 2020—as they have been in every presidential election since 1992, when Ross Perot got almost 24% of Arizona’s vote—even though neither state took much of a shine to Trump. A large portion of those two states’ populations live in relatively affluent suburbs around either Atlanta or Phoenix, and such voters played as Trump’s weakest suit. Given the pro-GOP track record of those states, and Trump’s unique ability to turn off suburban voters who want a president who comports himself more like a patrician, Republicans should feel confident that a future GOP nominee other than Trump can reclaim these two states. A much more challenging feat will be to match Trump’s success in the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi River region. The party, therefore, would seemingly be well served to run a nominee who can hold together the Main Street coalition that fared so well in that region.

All-American Agenda

It is often the case that good policy makes for good politics, and in many respects a Main Street agenda will be even more timely going forward than it was in 2016. The Biden-induced border crisis has made immigration even more of a pressing concern. International adventurism was dealt a further blow by Biden’s unconscionably inept withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. COVID-19 lockdowns, mask mandates, and other sundry decrees have disproportionately hurt small businesses, blue-collar workers, and Americans who lack the financial means to let their kids escape the public schools. The need to adhere to the separation of powers and federalism was made more evident by these kingly COVID decrees of executives and public health officials as they usurped legislative powers, by the vast differences in COVID policies across states (showcasing the virtue of federalism), and by the decision to exit Afghanistan as we entered—with a president, rather than Congress, taking it upon himself to decide whether we will be at war or at peace, contrary to what even Alexander Hamilton said the Constitution requires. Law and order, another aspect of a Main Street agenda, is at an ebb, while woke attacks against the likes of two biologically determined sexes, the hard-won colorblind ideal, and America’s history and heroes all require leadership in response that goes beyond doing the bidding of corporate America.

At its best, a Main Street coalition is pro-American and possesses a healthy skepticism toward cosmopolitan elites. It embraces policies designed to make it possible for everyday Americans—regardless of income, race, or creed—to prosper. This does not mean increased government handouts but merely having the government do its job with at least marginal competence or, more often, get out of the way. Such a coalition focuses more on Main Street than on Wall Street, more on small businesses than on multinational corporations, and more on the priorities of all 50 states than on those of the Acela corridor, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood. It embraces traditional American mores and resists attempts to fundamentally transform America.

The Main Street agenda appeals in Big Ten country, as Trump demonstrated. Exit polling in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa in 2016 found that voters in those states were generally more inclined than voters nationally to think that international trade takes away, rather than creates, U.S. jobs (by an average margin of 13 points across those five states, versus a margin of 3 points nationally). Meanwhile, voters most concerned about immigration favored Trump by an average of 55 points in those five states, versus 31 points nationally.

Trump lost by about the same amount nationally in 2020 (4.5 points) as Romney did in 2012 (3.9 points). Yet Trump fared 4.2 points better than Romney in Pennsylvania (losing by 1.2 points rather than 5.4), 6.3 points better in Wisconsin, 6.7 points better in Michigan, and a whopping 11 points better in Ohio and 14 points better in Iowa. (Trump also fared 4.2 points better in Florida.) If Republicans are to win in the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi River region, as they almost certainly must do if they are to win the presidency, their path to victory will presumably involve maintaining and building upon the Main Street coalition pieced together in large part by Trump.

To discount the generally decisive importance of the five states that form a ribbon from Pennsylvania, through Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin, to Iowa is to ignore not only the electoral map but also electoral history. In the 41 presidential elections dating back to Abraham Lincoln’s victory in 1860, the candidate who has won a majority of those five states has won the election 83% of the time. (Over the past century, that percentage has been essentially the same: 84%.) More than 60% of the time (26 out of 41 elections), one candidate has swept these five states, with those candidates posting a national win-loss record of 25-1 (96%), including Trump in 2016. (The sole exception was James Blaine in 1884.)

A Republican nominee who champions a Main Street agenda in 2024—and has the track record to show that he or she means it—would provide the GOP with the best chance of winning across this ribbon of five states as well as nationwide. The question is whether Republicans will embrace and advance this new Main Street coalition, which they have inherited more than built, or will revert to their old Big Business-focused, Chamber of Commerce-pleasing, establishment ways. The answer may well determine the outcome in 2024.