Books discussed in this essay:

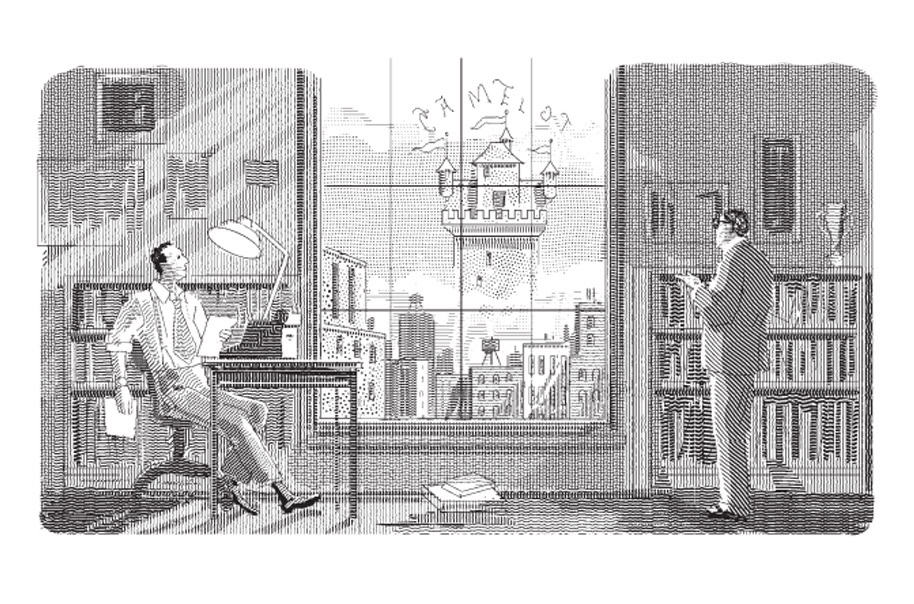

Camelot and the Cultural Revolution: How the Assassination of John F. Kennedy Shattered American Liberalism by James Piereson

Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement, by Justin Vaïsse

Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right, by Benjamin Balint

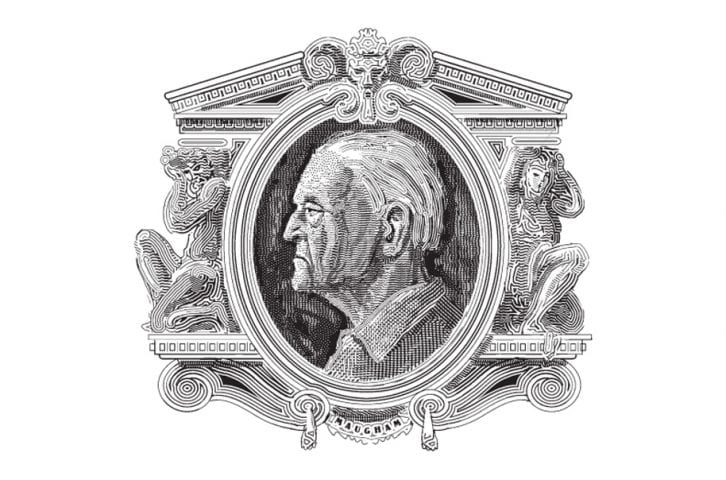

Norman Podhoretz: A Biography, by Thomas L. Jeffers

Neoconservatism: An Obituary for an Idea, by C. Bradley Thompson, with Yaron Brook

The publication of four books on neoconservatism in 2010 means that their authors were at work on them in the aftermath of the 2006 and 2008 elections. If the owl of Minerva flies at dusk, then those electoral beat-downs offered a promising moment to take stock of neoconservatism. Americans who knew just one thing about neoconservatives recognized them as the most prominent defenders of the war in Iraq, a war whose objectives the public found harder and harder to understand, and whose costs it found harder and harder to justify.

All four assessments of how neoconservatism ended up providing the rationale for an unpopular war add things to our political understanding. (It detracts from none of these books to point out that the best place to begin understanding Iraq and the neoconservatives is, well, Charles Kesler's "Iraq and the Neoconservatives," CRB, Summer 2007.) One of the fundamental questions is how a political enterprise that started out focused on domestic policy and cultural politics ended up being identified primarily with national security.

Beneath that question lies a more basic one. Neoconservatism, like so many other features of the 21st-century American landscape, is a product of the convulsions and contradictions of the 1960s. A neoconservative, according to Irving Kristol's famous aphorism, is a liberal who's been mugged by reality. That mugging took place during the 1960s, when the liberals who became neoconservatives joined millions of other Americans in winding up by the end of the decade inhabiting places they could not have imagined visiting at the beginning.

Defining the '60s

To understand the mugging we have to understand the realities. A good place to start is where the '60s started politically-John F. Kennedy's 1960 presidential campaign. Considering how many calendar benchmarks are brought to Americans' attention-happy 25th birthday, by the way, to New Coke and Back to the Future-it's striking that so little notice has been taken of the 50th anniversary of Kennedy's election. The Nixon-Kennedy debates generated a few 50-years-ago articles and TV stories in late September, since journalists are always happy to discuss events that rendered the media more important. Everything else that made such a big impression on Americans at the time-the doubts and pride about JFK's religion, the New Frontier, the candidate's glamorous family-has gone unremarked.

Perhaps the explanation is that America already commemorated Kennedy's victory in 2008, during Barack Obama's march to the White House. The dots practically connected themselves. Two of the youngest men ever to run for the presidency (Kennedy was 43 on Election Day, Obama 47), the first Catholic and first black president were both educated at Harvard, and better known as the authors of best-sellers than for their accomplishments in public life. Both overcame thin resumes by making a case to the voters that rested on personality and demeanor: not only did they present themselves as having the kind of character we should want in the Oval Office, but they and their avid followers were not shy about contending that it would speak well of Americans if they reached beyond religious and racial prejudice to bet on excellence.

The bigger reason for the absence of stories about 1960, however, is one that no one wants to talk about: the real JFK semicentennial will take place on November 22, 2013. "JFK's early death became part of everyone else's life," the critic Clive James wrote. "[People] never got over the death of Kennedy: it happened to them. They took it personally."

At this point there's not even anything that morbid about the prospect of spending November 2013 talking about Dallas, John-John's salute, and the eternal flame. As James Piereson argued in Camelot and the Cultural Revolution (2007), there were two Kennedy presidencies: the first, which began January 20, 1961, and ended November 22, 1963, was substantively modest and cautious. Best remembered for its style, it was a hit show to which the whole country had a ticket. The second Kennedy presidency, constructed quite deliberately after the assassination, was heroic and tragic, a quest too noble to overcome the enmity of this base, selfish world.

Kennedy's family and retainers pivoted instantly to make sure that his murder would be understood as a politically meaningful tragedy, rather than a senseless one. They labored strenuously and successfully to see JFK remembered "as a martyr for civil rights and equal justice for all," according to Piereson. It was the peculiar fate of a politician who had won the presidency by insisting on his support for the separation of church and state to bring about, by his death, a kind of amalgamation of religion and politics. Democratic Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield said in his eulogy of Kennedy,

He gave us his love that we, too, in turn, might give. He gave that we might give of ourselves, that we might give to one another until there would be no room, no room at all, for the bigotry, the hatred, prejudice and the arrogance which converged in that moment of horror to strike him down.

The Kennedy assassination triggered doubts about the destiny of our republic that have cast shadows over our political life ever since. The first-the real-Kennedy presidency, however, raised political questions that have also, more quietly, challenged America over the past 50 years. We will never know if John Kennedy, given one or five more years in the White House, would have resolved some of the contradictions between idealism and pragmatism, the two nebulous qualities to which he gave so much attention. We do know that the tension between them did a lot to define the '60s, and that America is still struggling to sort them out.

Trusting the Experts

Kennedy was not diffident about offering the nation moral leadership. In his acceptance speech at the 1960 Democratic convention he warned that

a dry rot, beginning in Washington, is seeping into every corner of America-in the payola mentality, the expense account way of life, the confusion between what is legal and what is right. Too many Americans have lost their way, their will and their sense of historic purpose.

His election would allow Kennedy not so much to direct as to catalyze a new patriotism that would be Spartan in its disdain for self-indulgence:

Woodrow Wilson's New Freedom promised our nation a new political and economic framework. Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal promised security and succor to those in need. But the New Frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises-it is a set of challenges. It sums up not what I intend to offer the American people, but what I intend to ask of them. It appeals to their pride, not to their pocketbook-it holds out the promise of more sacrifice instead of more security.

This challenge to forsake consumerism in order to advance America's "historic purpose" was summarized but not clarified by the famous imperative from Kennedy's inaugural address: "And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you-ask what you can do for your country."

The Kennedy Administration, however, had few good answers to those who took the president up on his challenge and asked what, specifically, they could do for their country. Yes, there was the Peace Corps, the Kennedy initiative whose name conveyed the idea that ordinary citizens could be secular missionaries if they acquired, or at least mimicked, the qualities of discipline, commitment, and sacrifice essential to soldiering. The other stirring challenges, such as landing a man on the moon, were collective enterprises in which the vast majority of Americans participated only as taxpayers and awed spectators.

As a rule, in fact, the big problems Kennedy saw required expertise, and little else. Amateurs' enthusiastic intrusions were at best distractions and at worst impediments. Addressing a White House conference on the economy in May 1962, Kennedy spoke of the "difference between myth and reality":

Most of us are conditioned for many years to have a political viewpoint, Republican or Democratic-liberal, conservative, moderate. The fact of the matter is that most of the problems, or at least many of them, that we now face are technical problems, are administrative problems. They are very sophisticated judgments which do not lend themselves to the great sort of "passionate movements" which have stirred this country so often in the past.

In a commencement address at Yale the following month, Kennedy reiterated the point:

What is at stake in our economic decisions today is not some grand warfare of rival ideologies which will sweep the country with passion but the practical management of a modern economy. What we need is not labels and clichés but more basic discussion of the sophisticated and technical questions involved in keeping a great economic machinery moving ahead.

One thing you could do for your country, then, was to pipe down and stop pestering the experts who were grappling with the hard problems of managing it. An implicit part of the rationale for the Peace Corps was squaring the circle by democratizing expertise. Although you probably had nothing worthwhile to contribute to the debates over public policy in a complex society like America in the 1960s, you could be an expert-the expert-to whom all the other village inhabitants would turn respectfully and gratefully for instruction on everything from irrigation to child nutrition, if only you brought a good education and can-do attitude to the brisk orientation program that prepared you for your posting in the jungles of Borneo.

For those who remained stateside, making citizenship meaningful in a nation where experts handled all the big problems posed a dilemma. Four days after President Kennedy spoke at Yale, the first convention of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) adopted the "Port Huron Statement." It showed that the idealism JFK invoked amorphously would not compliantly accede to the pragmatism he endorsed more specifically. "All around us there is astute grasp of method, technique" the statement read, "but, if pressed critically, such expertise is incompetent to explain its implicit ideals."

Thus did the Kennedy presidency midwife a New Left, the newness of which consisted in its indifference to Marxist dogma in favor of "participatory democracy," which would mean whatever its participants democratically determined it ought to mean. Seeing "little reason why men cannot meet with increasing skill the complexities and responsibilities of their situation," the SDS in the Port Huron Statement proclaimed the "root principle" that "decision-making of basic social consequence be carried on by public groupings." The organization later distilled this idea into the aphorism, "Democracy is an endless meeting"-the best marketing slogan tyranny ever had.

Sociology, Not Ideology

The ways in which Americans lost confidence after Kennedy's assassination did not immediately include doubting the expertise of the experts. Nor did the experts doubt their own. In the wake of Lyndon Johnson's landslide victory in 1964, "big-government liberalism was in a triumphant mood," according to John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge's The Right Nation (2004). Keynesian economists thought they had cracked the code that would guarantee "the world would go on getting richer," while other "policy makers thought they had the power to cure social ills, from poverty to prejudice, and most Americans still trusted them to do so."

The Public Interest, a quarterly which first appeared in 1965, posed a much more qualified challenge to the technocrats than did the Port Huron Statement. Its initial goal was "to bring advances in sociology to bear on debates concerning American society and public policy, while avoiding preconceptions, cliché, sentimentality, and ideology," writes Brookings Institution senior fellow Justin Vaïsse in Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement. As such, the journal would be a corrective to the social reforms advanced by liberal activists and philanthropists, many of which were "hastily conceived, shortsighted, naively optimistic, and interventionist."

The key, said founding editors Daniel Bell and Irving Kristol in the first issue, was "[k]nowing what one is talking about," a "deceptively simple phrase that is pregnant with larger implications." One of those implications was that although social science was necessary for social reform, the true social scientist, like Socrates, was aware above all else of what he didnot know about how society worked and how government initiatives would work out. James Q. Wilson, who became a frequent Public Interest contributor, wrote last year in the Wall Street Journal that the "view that we know less than we thought we knew about how to change the human condition" united the "policy skeptics," who defined the Public Interest's worldview. They "thought it was hard, though not impossible, to make useful and important changes in public policy."

No one, presumably, opposes in principle arriving at a better understanding of public policy design and implementation, and using it to make government initiatives work as well as possible. Of course, practicality is never quite as simple or detached at that. As political scientist James Ceaser has noted, "Pragmatism is the magic word to describe what liberals want, but do not want to argue for."

Liberals in the 1960s believed that what they wanted they no longer needed to argue for. The Affluent Society, expected to continue forever, had vindicated liberal economics, and Barry Goldwater's lopsided defeat in 1964 had vindicated liberal politics. These victories marked not merely the advance but the culmination of liberalism and the dawn of a post-ideological age destined to be long and happy. Liberalism had ceased to be an -ism, and would henceforth stand simply as the purposeful embodiment of decency and intelligence.

Countering the Counterculture

Although the public interest came, in time, to question the idea that liberalism was decent and intelligent, it was not started for that purpose. No one who edited or wrote for it supported Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign in 1964, or even took it seriously. "For the first few years of its existence," writes Vaïsse, "the journal was seen as a reasonable and moderate liberal publication." James Q. Wilson, for instance, points out that he voted for Kennedy, Johnson, and Hubert Humphrey in the three presidential elections in the 1960s, and worked on Humphrey's 1968 campaign.

But the effort to offer fellow liberals helpful advice was soon complicated by startling tectonic shifts. The Public Interest'spolicy skepticism quickly proved insufficiently skeptical. The sociologist Nathan Glazer, involved with the journal from the beginning and co-editor for 30 of its 40 years in print, wrote in the valedictory issue in 2005:

Managing social problems was harder than we thought; people and society were more complicated than we thought…. We began to realize that our successes in shaping a better and more harmonious society, if there were to be any, were more dependent on a fund of traditional orientations, "values," or, if you will, "virtue," than any social science or "social engineering" approach.

Many traditional orientations, assumed to be durable, came under siege in the years immediately following the Public Interest's founding. Events "soon overtook" the "realistic meliorists" who started the magazine, Irving Kristol wrote in 1995. The biggest such event was "the student rebellion and the rise of the counterculture, with its messianic expectations and its apocalyptic fears…. Suddenly we discovered that we had been cultural conservatives all along."

What really conservatized the people who came to be called, pejoratively at first, neoconservatives was the intellectual dishonesty and moral cowardice shown by conventional liberals when confronted by this radical, violent, incoherent Left. "Cool criticism of the prevailing liberal-left orthodoxy," according to Kristol, "was not enough at a time when liberalism itself was crumbling before the resurgent Left." The New Left demanded, as every Left does eventually, "Which side are you on?" Principled, tough-minded opposition to Henry Wallace and his fellow travelers had defined what Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., called in the 1940s liberalism's "vital center." Liberals in the 1960s, however, couldn't bear the enmity and scorn of the New Left. During the 1968 student takeover of Columbia University, SDS leader Mark Rudd boasted to the university president in a letter, "We will destroy your world, your corporation, your University." Schlesinger's stout defense of academic freedom against such assaults was, "Both Berkeley and Columbia will be wiser and better universities as a result of the student revolts."

The neoconservatives, by contrast, were the former liberals who refused to tolerate, much less applaud Tom Hayden and Stokely Carmichael's menacing rhetoric and conduct. The vehement rhetoric and violent actions of the late 1960s, which supplanted the idealism so many had responded to at the beginning of the decade, was particularly important in turning a second publication, Commentary, into an organ of neoconservatism. Two new books-Running Commentary, by Hudson Institute fellow Benjamin Balint; and Norman Podhoretz: A Biography, by Thomas Jeffers, a professor of literature at Marquette University-tell the story well. Founded in 1945 by the American Jewish Committee, Commentary at first, under Podhoretz's editorship, embraced much of 1960s radicalism. It serialized Paul Goodman's Growing Up Absurd, for example, which became a foundational text for the counterculture and New Left.

The civil rights movement, with its commitment to overcoming bigotry by relying on peaceful resistance and appealing to the better angels of our nature, had taken idealism to the point of secular sainthood and in some cases martyrdom. The movement had promised the integration of blacks into every aspect of American society, and a marked increase in the spirit of brotherhood. Even during this optimistic phase of the civil rights era, when mere good will was thought to be the sufficient condition for racial harmony, Norman Podhoretz had foreseen that turning America into a successful multi-racial republic would be a very daunting endeavor. "My Negro Problem-And Ours" appeared in Commentary in February 1963, offering, in Thomas Jeffers's words, "something to offend everyone: integrationists, black nationalists, Jews, and whites generally." So bleak was Podhoretz's assessment of the prospect for black and white Americans securing equality and fraternity that he ended up saying that the only solution to America's racial tensions would be "the wholesale merging of the two races," after mixed marriages had reduced racial plurality to a new singularity.

This pessimism, which seemed extravagant in 1963, looked increasingly prescient as the decade went on. The conduct and rhetoric of the black power movement caused incalculable damage after it eclipsed the more conciliatory civil-rights approach in the mid-'60s. Again, mainstream liberals mindlessly followed the Zeitgeist. No one had objected in 1963 when President Kennedy emphasized the importance of lawfulness and reciprocity to race relations: "We have a right to expect that the Negro community will be responsible, will uphold the law, but they have a right to expect that the law will be fair, that the Constitution will be color blind." Two years later, however, his brother Robert, by then a senator from New York, disdained former president Dwight Eisenhower's call for "greater respect for law" in response to the riot in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. To the contrary, said Senator Kennedy, "There is no point in telling Negroes to obey the law. To many Negroes, the law is the enemy." The following summer Vice President Humphrey voiced his support for moderation and lawfulness by saying, "If I were in those [slum] conditions, you'd have more trouble than you have already because I've got enough spark left in me to lead a mighty good revolt."

Under this new dispensation, the default liberal interpretation of any friction within or beyond America's borders was that the lighter-skinned party to the conflict was always presumed guilty until proven innocent. Relations between blacks and Jews, which had been strengthened by the civil rights movement, deteriorated especially sharply. There were so many straws it would be hard to say which was the last. One good candidate would be the reaction to 1967's Six-Day War, when black militants and New Leftists declared Israel the aggressor and oppressor. "After the war," writes Balint, "it no longer seemed a question of twenty Arab states bent on Israel's annihilation, but of a Palestinian minority fighting a powerful oppressor for a national homeland. The liberal conscience had found a new cause."

Paleoliberalism

Neoconservatism and its adversaries have been preoccupied with national security for so many years that it is easy to forget that the original focus was on domestic issues. Journalist Peter Steinfels wrote a long, thoughtful book in 1979, The Neoconservatives, that never mentioned foreign policy. It wasn't until 1985 that Irving Kristol started the National Interest as a counterpart to the Public Interest. Commentary had addressed foreign policy questions from the time it was founded, and continued after Podhoretz became its editor in 1960. Its viewpoint throughout, however, was that of Cold War liberal anti-Communism. According to Balint, the magazine "had from the beginning considered the Soviet Union not a worker's paradise but a grave threat to democracy."

Vaïsse, Balint, and Jeffers all make clear that the antiwar movement of the 1960s caused liberal anti-Communists to become anti-anti-Communists, leaving a void filled by the neoconservatives. In Why We Were in Vietnam (1982), Norman Podhoretz detailed the blithe indifference of the antiwar movement to basic realities in Southeast Asia. The critic Susan Sontag's visit to North Vietnam, for example, led her to write that it was "a place which, in many respects, deserves to be idealized." Indeed, she contended, "incorporation in such a society [would] greatly improve the lives of most people in the world." The book concludes that Ronald Reagan, accused of committing a blunder, merely told the truth during the 1980 campaign when he called the war in Vietnam "a noble cause." Podhoretz laments that the antiwar movement's power in the media and campuses rendered "the American effort to save Vietnam from Communism…beyond our moral and intellectual capabilities."

In 1984 President Reagan's ambassador to the United Nations, Jeane Kirkpatrick, said in the same vein that contemporary Democrats "always blame America first." Before joining the Reagan Administration she had written in Commentary, "The central aspect of the antiwar movement was less its rejection of the Vietnam War than its rejection of the United States." Kirkpatrick quoted Jean François Revel in her speech to the 1984 Republican convention: "Clearly, a civilization that feels guilty for everything it is and does will lack the energy and conviction to defend itself." Thus do "culture wars" in a democratic society shape every political challenge, including whether to wage, and how to win, shooting wars.

John Kennedy's 1961 inaugural address proclaimed that Americans would pay any price and bear any burden "to assure the survival and success of liberty." Eleven years later the Democratic platform, after promising an immediate withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Vietnam and the subsequent termination of all military aid to the government in Saigon, stated, "We will do what we can to foster an agreement on an acceptable political solution [to the sovereignty of South Vietnam] but we recognize that there are sharp limits to our ability to influence this process, and to the importance of the outcome to our interest."

Whatever-it-takes Democrats held sway for roughly 20 years after World War II, while do-what-we-can Democrats have dominated the party for more than twice that long, and show no sign of yielding control. The brevity of Cold War liberalism's ascent, and its vehement, enduring repudiation in the 1960s by liberals allied with or intimidated by the New Left, argue that the aberration came before the 1960s, not after. The disaffected liberals who became neoconservatives slowly and reluctantly realized that George McGovern did not betray liberalism; he personified it.

The neoconservatives abandoned liberalism after trying to rescue it, first, from social engineers' hubris and then from consanguinity with the New Left. After giving up on '60s and '70s liberalism's understanding of national security and cultural solidarity, both of which blamed America first, the neoconservatives' final connection to liberalism was their continuing support for the welfare and regulatory state. According to Jeffers's biography of Podhoretz, the neoconservatives "were faithful to the liberalism that had guided the activist, Democratic presidents of their youth-Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy-who had been progressive at home and anti-totalitarian abroad." "Paleoliberalism," Jeffers suggests, would have been a more accurate term for their position.

Justin Vaïsse's chronicle of the efforts to wrest the Democratic Party away from McGovernites through groups like the Coalition for a Democratic Majority and the Committee on the Present Danger shows how much hope the neoconservatives invested in Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson of Washington. Jackson was indeed an unapologetic Cold Warrior, who complicated life for Republican and Democratic presidents during détente with his determined efforts to highlight and stymie Soviet human-rights violations. Jackson was equally unabashed, however, in his enthusiasm for Big Government. His response to the 1970s oil crisis, for example, was to propose a National Energy Production Board, "an energy superagency," according to one news account, "that would establish priorities, let huge contracts and even set up new companies for specific jobs."

Conservative Welfare State

Little wonder, then, that other conservatives found it hard to muster two cheers, or even one, for neoconservatism. InNeoconservatism: An Obituary for an Idea, Clemson University politics professor C. Bradley Thompson argues (with Ayn Rand Institute executive director Yaron Brook) that what's neo in neoconservatism obliterates most of what's conservative in it. As the similar titles imply, Thompson's book agrees on at least one point with Norman Podhoretz's 1996 article "Neoconservatism: A Eulogy": neoconservatism "no longer exists as a distinctive phenomenon requiring a special name of its own," as Podhoretz put it. In other words, neoconservatism is conservatism now, and conservatism is neoconservatism.

Where Podhoretz and Thompson differ is on whether this is a good or bad development. For Podhoretz, neoconservatism has been successfully incorporated into conservatism, deepening conservatives' understanding of America's perils and equipping them with stronger arguments for carrying out their work. Thompson, by contrast, laments that "the larger conservative movement has been absorbed into the neoconservative movement," to the detriment of the older conservatism exemplified by the Goldwater campaign, "with its proclaimed attachment to Jeffersonian principles of individual rights, limited government, and the free enterprise system."

"Unlike the older schools of American conservatism," writes Podhoretz, the neoconservatives

were not for abolishing the welfare state but only for setting certain limits to it. Those limits did not, in their view, involve issues of principle, such as the legitimate size and role of the central government in the American constitutional order. Rather, they were to be determined by practical considerations, such as the precise point at which the incentive to work was undermined by the availability of welfare benefits, or the point at which the redistribution of income began to erode economic growth, or the point at which egalitarianism came into serious conflict with liberty.

Nonetheless, he continues, neoconservatives moved right on that question as they became incorporated into the larger conservative movement:

If [neoconservatism] originally differed from the older varieties of conservatism in wishing to reform rather than abolish the welfare state, few traces of that difference remain visible today. By now most neoconservatives have pretty well given up on the welfare state…. [T]here is hardly any disagreement over the harm the welfare state has done in fostering illegitimacy and all the terrible social pathologies that flow from babies having babies. Nor is there any disagreement over the desirability of working to get rid of the welfare state, or at least as much of it as is politically possible."

Thompson isn't buying it. No matter how it's explained or justified the "conservative welfare state" that Irving Kristol called for on many occasions is, in Thompson's view, a contradiction in terms. "The difference between the neoconservatives' ‘conservative welfare state' and the modern liberal welfare state is one of degree only," Thompson writes. And the fundamental principle of any welfare state is that

the fulfillment of a "need" is something to which one is morally entitled, which in turn makes it a "right." Further, this is a "right" that can and should be "demanded" without apology, responsibility, or gratitude, and that can be satisfied only through the redistributive and coercive power of the State.

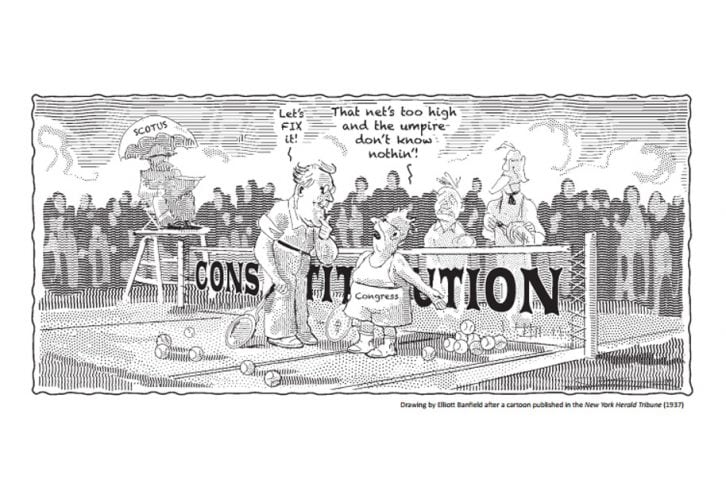

A House Divided

On the question of the welfare state and Big Government more generally, conservatism is a house divided. It has clear, categorical arguments against permitting American government to take up any task it did not perform during Jefferson's presidency. For all the effort spent to make the limited government syllogisms fit together seamlessly, however, the results have a long history of faring better in seminar rooms than in polling booths. In 1936 and 1964 the Republicans' presidential candidates, after repeatedly expressing their commitment to these principles, won 36.5% and 38.5% of the popular vote, respectively. The party's platforms in those years were some of the longest suicide notes in American political history.

The neoconservative inclination to reduce the welfare state as much as politically possible is better attuned to public opinion, but less equipped to do anything to shift it. Neoconservatives can appeal to the public's belief that welfare programs are the oxygen sustaining social pathologies, but cannot appeal from any principles that challenge the welfare state's legitimacy or limit its scope. If the idea that welfare benefits are entitlements-rights-stands unchallenged, the welfare state will grow in size and strength, punctuated by occasional and temporary cutbacks of particularly dubious programs. Its expansion will, in short, be as relentless and impervious to political opposition as the growth of America's welfare state has been over the past 75 years.

The alternatives, then, appear to be a principled disdain of the popular attachment to government programs for enhancing economic security, or the acquiescence in the central principle of the welfare state, according to which it does nothing but grow. If that's the case, conservatives must hope the synthesis of their divergent domestic policy viewpoints is still a work in progress. Its successful completion will require statesmanship that applies the principles of government dedicated to the protection of natural rights to modern circumstances, where the vast majority of people, even very prosperous ones, spend their entire adult lives as employees whose well-being depends heavily on forces over which they have little control.

A good mid-range goal for this statesmanship would be to secure a consensus around the idea that a conservative welfare state differs from the liberal one in kind, not just as a matter of degree, because it rejects the assertion that rights to government benefits exist or can be fabricated by politicians, elections, or history's evolving standards. The civics class truism that rights cannot exist without obligations does not pave a two-way street. However compelling the moral obligation of a decent society to assist its members who face wretched, precarious, or degrading lives through no fault of their own, it does not confer on anyone a right to receive such assistance. Given the way decades of liberal governance have reinforced our strong tendency to believe any agreeable arrangements we have grown accustomed to are ones we have become entitled to, this is not a principle the architects of a conservative welfare state ought to stipulate once before moving on to other business. Rather, the success of their enterprise will require that its programs, and the rhetoric justifying those programs-constantly uphold the importance of helping the needy, without displacing or diminishing the practical need and moral imperative for individuals, families, and communities to help themselves and one another.

The questions raised but not settled in the 1960s remain on America's docket half-a-century later. Our society struggles to reestablish the standards of respectable behavior besieged by that decade's new frontier of indulgent self-expression. It turns out that the stifling, sometimes hypocritical old moral codes did a better job than the new, liberating ones at protecting vulnerable children who suffer for the lack of two parents committed to them above all else. This legacy of private irresponsibility corresponds to one of public irresponsibility, as our debts rise inexorably and our discourse increasingly treats other people's failure to agree with our politics as the result of their intellectual, psychological, and moral deficiencies.

The Tea Party movement has now taken up the Goldwater conservatives' mission of reestablishing firm constitutional limits on the scope of modern government. Its populism takes issue with John Kennedy's idea that the complexity of modern problems leaves no choice but to delegate a large share of decision-making to credentialed experts. Instead, the Tea Party movement aligns with the Public Interest conviction that if the experts know much less than they think they do, they may not know much more than the rest of us. Seeing no reason to retire from public engagement, the Tea Party evinces a sincere determination to ask what citizens, as citizens, can do for their country, and to find answers that matter here at home, not just in impoverished nations thousands of miles away.