Books Reviewed

“Aristocracy is not an institution,” G.K. Chesterton wrote, “aristocracy is a sin.” It is “the drift or slide of men into a sort of natural pomposity and praise of the powerful, which is the most easy and obvious affair in the world.” With the best and most exalted of intentions, this is exactly what historian Jon Meacham has recommended to Americans in his new book, The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels. The better angels he describes are all on the side of an aristocracy—those who know better, live better, and are better than the benighted majority who surround them.

A former editor-in-chief of Newsweek magazine and author of a Pulitizer Prize-winning biography of Andrew Jackson, Meacham believes no one speaks better for the better angels than the president of the United States—or at least certain presidents, who have had the instinctive twitch of the nose for what he calls the “forward motion” of America. Americans, he explains, do not have what sociologist Gunnar Myrdal once called a “creed”; they have a “soul,” which Meacham defines as “the vital center, the core, the heart, the essence of life.” Souls being wayward and unpredictable, the American soul has not always followed the direction appropriate for souls, which is supposed to be “forever upward.” Happily, however, there are presidents with the soulful touch, and a “president of the United States with a temperamental disposition to speak to the country’s hopes rather than to its fears” will be our best guide to the sunny uplands Meacham descries in our future.

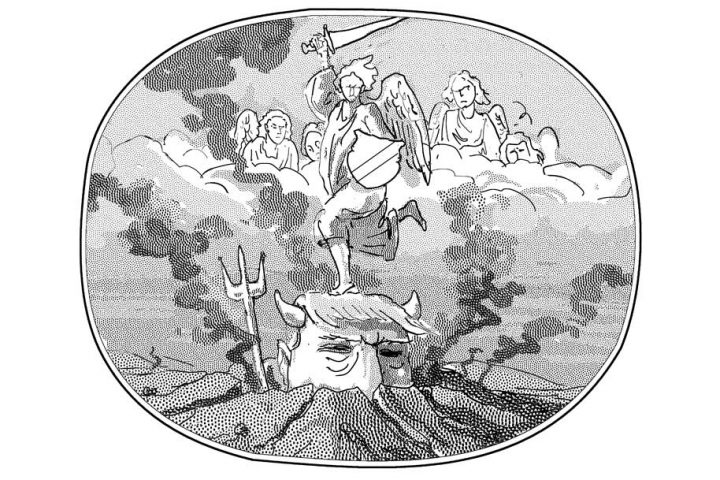

Unhappily, there have also been soulless presidents, and Meacham is not shy about fingering one of the more recent of these defaulters, Donald J. Trump. This makes The Soul of America less a history of the presidency and more an episodic diatribe against the sitting president, since each moment when fear and failure have reared-up in American life is sure to have some connection to Trump. (The young Trump was once a client of Roy Cohn, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s lawyer, Meacham whispers, and is “the heir” of George Wallace.) The Soul of America actually began as an essay for Time magazine, in the wake of last summer’s Charlottesville riot, which expanded into a series of pieces for the New York Times Book Review, with the single message that President Trump was cynically whipping-up America’s populist fears in order to mobilize “the alienated” who have been left behind by “changing demography, by broadening conceptions of identity, and by an economy that prizes Information Age brains over manufacturing brawn.”

* * *

The condescension displayed in that single sentence toward those who are not-Meachams—people who are too thick to sense a “changing demography,” too unsophisticated to appreciate “identity,” and too simian to savor the victory of Instagram over welding—is performed so swiftly and so carelessly that it is difficult to believe that Meacham believes they even deserve to be considered his fellow citizens. In pursuit of an American Soul, he has passed glibly over the wreckage of the American Body Politic, and leaves open the question of whether the fear Trump inspires in Meacham could just as easily be the hope that Joe Sixpack has been nursing since the factories in Youngstown, Ohio, went dark and Ross Perot predicted the great NAFTA sucking sound.

“America has been defined by a sense of its own exceptionalism,” Meacham writes, as though his book is designed to be yet another entrant in the Democracy in America sweepstakes. He proposes that “the dominant feature” of the American Soul “is a belief in the proposition, as Jefferson put it in the Declaration, that all men are created equal,” which Meacham understands to dictate more or less equal outcomes for all identity groups. He forgets that being “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” is the product of having been first “conceived in liberty,” an object which falls so entirely off his screen that he eventually comes to regard it as little more than a tool for promoting political fear. He insists doggedly that true equality will not be realized without the direction of a very tiny cadre of philosopher-presidents, who have shouldered the responsibility of enlightening, and occasionally manipulating, Americans into following the ever-widening project of equalization.

At that moment, The Soul of America turns from pursuing a Tocqueville-style project about the fundamentals of American life, into a new, improved version of John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage, in which Americans will ineluctably achieve a state of egalitarian grace through the executive branch’s inspired direction. Such a result is guaranteed by a kind of deus vult—what Martin Luther King, Jr., called “the arc of the moral universe”—and by the development of the American presidency into an “elective kingship” (a phrase Meacham borrows from political scientist Henry Jones Ford, a disciple of Woodrow Wilson). Never mind that there are no moral arcs in the universe that come with political directions attached. Never mind, either, that presidents are, as Barack Obama conceded, only presidents. There is, Meacham replies, “no understanding of American life and politics…without a sense of the mysterious dynamic between the presidency and the people at large.” The term “constitution” makes no appearance in his book’s index.

* * *

The first significant exhibit in this presidential cargo-cult is Theodore Roosevelt. Even then, Meacham acknowledges that “it would be a mistake to hold Roosevelt up as a forerunner or as a prophet of the racially and ethnically diverse America of the twenty-first century.” (Indeed it would, since Roosevelt cheerfully endorsed visions of Anglo-Saxon racial superiority.) But T.R. is at least a beginning, winning back points for himself by embracing “the progressive passion for reform” and for occasional good deeds on behalf of black Republicans like Booker T. Washington, Minnie M. Cox, William Crum, and John R. Lynch.

They will also be the last Republicans Meacham lauds, since thereafter The Soul of America turns into the Golden Legend of the Democratic Party, beginning with Woodrow Wilson. Despite his uneven stance on reform (for women’s suffrage, but also for segregated federal hiring), Wilson becomes the shining example of a presidential supreme leader. It seems to bother Meacham not at all that Wilson’s concept of political leadership has all the evocations of organic national unity that become the hallmarks of fascism. “What a lesson it is in the organic wholeness of Society, this study of leadership!” Wilson announced. “In the midst of all stands the leader…reckoning the gathered gain; perceiving the fruits of toil and of war and combining all these into words of progress, into acts of recognition and completion. Who shall say that this is not an exalted function?” Certainly not Jon Meacham. But unbridled leadership does not necessarily lead upwards, much less away from fear-mongering, something which Wilson demonstrated in spades through Prohibition, the Federal Reserve, the income tax, the Espionage Act (the Progressives’ ultimate domestic achievements), and the League of Nations (their ultimate international achievement).

Nor do we go much further into Meacham’s history before we find fear-spurning politicians dealing out quite malevolent quantities of fear in furtherance of Meacham’s righteous purposes. The apex of fear-refusing presidents is, of course, Franklin Roosevelt, who assured Americans in 1933 that they had nothing to fear but fear itself. But FDR never hesitated to brandish fear as a weapon when he played interest-group politics, accused the Supreme Court of protecting “the right under a private contract to exact a pound of flesh,” and denounced “economic royalists” and “malefactors of great wealth” (a term he borrowed from cousin Teddy). Meacham lauds Roosevelt’s “sense of hope, a spirit of optimism forged in his own experience.” Yet, if there was anyone talking hope and optimism in 1940, it was the luckless Republican candidate Wendell Willkie.

* * *

Ironically, the fears Meacham denounce as the most toxic—those of Joe McCarthy, naturally—were the ones that, 40 years after McCarthy’s death, turned out to be the ones to which Americans really did need to pay serious attention. Meacham assumes that McCarthy had no grounds whatever for his shrill denunciations of Soviet agents within the federal government (“the Soviets had made strides in penetrating Washington in the 1930s and early ’40s, but a loyalty program had rolled up many of the agents,” Meacham soothes), and so the Rosenbergs, Klaus Fuchs, and Alger Hiss (“the urbane New Deal lawyer”) pass by with nary a flutter. What we have learned since is that several hundred Americans deliberately cooperated with Soviet espionage in the 1930s and ’40s, fewer than two dozen of whom were ever prosecuted. The problem of the 1950s was not fear, but (thanks to Tailgunner Joe and the John Birch Society) the failure to fear rightly.

Meacham’s prime example of how fear-fleeing presidents have carried the banner of equality up the alpine heights is Lyndon Baines Johnson. He has no greater hero than Johnson, whose “commitment to the cause” of civil rights after JFK’s assassination “forms one of the great chapters of personal transformation and of political courage in the history of the presidency.” Johnson “dismissed” all pragmatic counsels “to go slow and play it safe,” and used both his personal political influence in Congress and the bully pulpit of the presidency to move the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. To achieve the goal of practical racial equality, Johnson was even willing to surrender “the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.” Greater love hath no president than to give up his votes to his enemies. (Except, of course, that the South was being lost to the Republican Party for a long time before the Civil Rights Act: half of the old Confederate States went for Dwight Eisenhower in 1956; two went for Richard Nixon in 1960, while Texas, Johnson’s own state, and South Carolina only went Democrat by 2% of their popular vote.)

One of the prices to be paid for Meacham’s exaltation of Johnson is the effacement of black agency in the civil rights struggle, as MLK, John Lewis, and the Selma marchers are reduced to little more than tokens in Johnson’s strategizing. “Lyndon Johnson was never the anonymous donor,” recalled former Johnson White House fellow Doris Kearns Goodwin, “his was a most visible benevolence which reminded recipients at every turn of how much he had done for them.” Nor was Johnson entirely a paragon of egalitarian virtue. He might accept the loss of the old South to the Republicans, but he was aware that the civil rights legislation would compensate for that loss. Oddly, Meacham never opens up the one aspect of Johnson’s presidency for which he is principally remembered, and which was almost entirely driven by fear: the Vietnam War is only discussed once, in three paragraphs.

* * *

What role does fear play in a democracy? It is routine to deplore fear in politics, since it seems to carry with it the threat of mob rule, intolerance, and lynch law. But fear can be sometimes as prophylactic as it is sometimes paranoid. Anyone who would like to take a good measure of the role played by fear in the American Founding ought to read the entirety of the Declaration of Independence, where fear of George III fairly screams off the vellum.

In Jon Meacham’s imagination, politics is a gradual, linear evolution from what has been to what will be, from the known but passé to the unknown and disturbing, and so it requires an elite few, intelligent enough to discern the next upward turn and interpret it to the fearful masses who will follow. This was not the understanding of the founders. The path they pursued was a return to first principles and natural law after dark centuries spent wandering in the artificial, irrational mazes of aristocracy and privilege. The possibility that government might turn again, under temptation or force, into the old circle that led to aristocracy preyed on their minds. Rather than serenely scaling new heights of novelty, government is “perpetually degenerating towards corruption,” as Samuel Johnson put it, and “must be rescued at certain periods by the resuscitation of its first principles, and the reestablishment of its original constitution.” But that is precisely what Meacham mistakes for fear. Only aristocrats, possessing the praise of the powerful, understand it as their enemy.