Books Reviewed

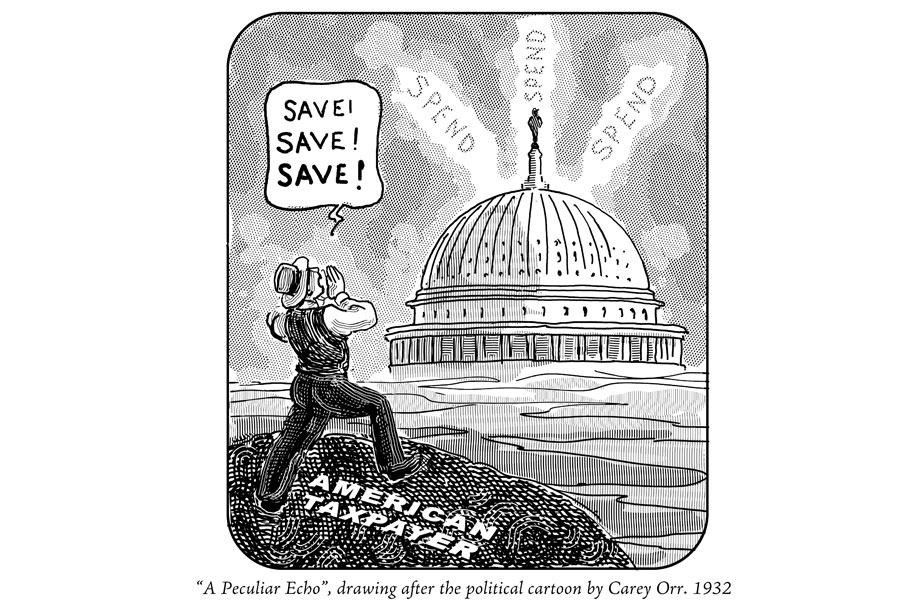

For growing numbers of Americans, our country has become a rotten place to live. The wealthy can still believe in the American Dream of steady advancement, year to year and generation to generation. For everyone else, the hope that they and their children can achieve or preserve a comfortable, respectable, and secure standard of living has become a cruel mirage. We need not despair, however. Wise and humane governance sustained the American Dream through the middle of the 20th century. Foolish, cruel policies that began with Ronald Reagan’s election to the presidency in 1980 caused insecurity and misery to become widespread. The key to reclaiming broadly shared prosperity is to end our long, lamentable detour from vigorous government regulation and income redistribution, a commitment that defined domestic policy from Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal through the 1970s.

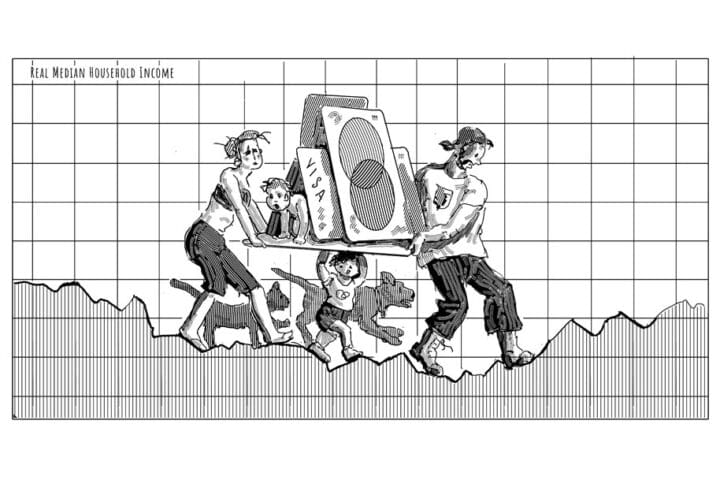

Shorn of nuances, this is the core argument of Ours Was the Shining Future: The Story of the American Dream, the first book written by David Leonhardt, a veteran New York Times journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 2011. The U.S., he argues, is “suffering through its worst period of stagnation in living standards since the Great Depression.” The economic torpor has affected the affluent far less severely than everyone else. Relying on research by Harvard economist Raj Chetty, who examined thousands of families’ anonymized income tax returns over a span of decades, Leonhardt contends that an American born in 1940 had a 92% likelihood of achieving a higher inflation-adjusted income than his parents, but one born in 1980 had merely a 50% chance to enjoy an adulthood more prosperous than his childhood. Should this decline continue, it will become the rule rather than the exception for children to make less and live worse as adults than their parents did.

***

Leonhardt takes his title from the closing words, “Mine is the shining future,” of The Epic of America (1931) by historian James Truslow Adams, the bestseller that made the phrase “the American dream” part of the nation’s vernacular. Leonhardt’s switch from the present to the past tense conveys the warning that, without a course correction, our best days are behind us.

Such jeremiads have long been the staple of Democratic politicians’ speeches and liberal pundits’ newspaper columns. Since Donald Trump’s 2015 escalator ride, the indignation has become more bipartisan. In his 2017 inaugural address, most famously, Trump decried the “American carnage” of “children trapped in poverty in our inner cities” and “rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape.” The “wealth of our middle class,” he continued, “has been ripped from their homes and then redistributed across the entire world.”

Republicans are struggling to devise a policy agenda that addresses these problems while also honoring conservatism’s foundational commitment: to align government’s responsibilities and the mechanisms it employs to discharge them with the Constitution’s strictures and principles. No such fears about plenary government torment those on the left side of America’s political spectrum. Leonhardt, for example, endorses capitalism but distinguishes “democratic” (or “moral” or “managed”) capitalism, which he favors, from what he calls (more than a dozen times) “rough-and-tumble” capitalism, wherein “taxes are low, corporations behave largely as they want, and a laissez-faire government allows market forces to dominate.”

It is not necessary to agree with such politics to admire his book. As its subtitle implies, Ours Was the Shining Future tells a story to make an argument. His story about declining economic prospects is interesting and clear, and the argument cogent. Leonhardt’s assessment of limited-government conservatism, in particular, passes the ideological Turing Test: people who believe in Reaganite precepts will find them recognizable, rather than tendentiously caricatured. By the same token, Ours Was the Shining Future is often strongly critical of the Democratic Party, especially regarding what Leonhardt, following economist Thomas Piketty, calls the “Brahmin left,” which has been blithely indifferent to the harm that working-class Americans suffer from economic upheaval, crime, and immigration.

***

Despite these considerable virtues, the book fails to achieve its central goal. Both its diagnosis of declining mobility, and its prescription of a vast increase in government spending, regulation, and redistribution are weaker than the logic and evidence that contradict the book’s thesis.

Concerning what Leonhardt terms the “Great American Stagnation,” two American Enterprise Institute (AEI) researchers, Michael R. Strain and Scott Winship, have identified serious problems with the ubiquitous argument that a declining standard of living has become the new normal. Strain’s arguments are collected in his 2020 book, The American Dream Is Not Dead. Winship has published many studies, of which his three-part report, “Economic Mobility in America,” is the most recent and comprehensive installment.

One important consideration is that households are smaller now than they were during the post-World War II economic and baby booms. In a 2015 Forbes magazine article, Winship pointed out that, for Americans in their thirties, the average household size was 4.6 in 1970 and 3.6 in 2010. Fifteen percent of those between the ages of 30 and 40 were childless in 1970, compared to 34% in 2010. And of those who did have children, the average number of children declined from 2.9 to 2.1 during that 40-year period.

The statistician’s tool for comparing the incomes of households of different sizes is to divide income by the square root of the number of household members. Using this adjustment, a single person with an income of $50,000 has an economic standard of living equivalent to that of a household of two living on $70,711, a family of three making $86,603, a family of four with an income of $100,000, or a family of five receiving $111,803. It’s like a calculus problem: as a household gets larger it needs more income to maintain the same standard of living—but these income requirements increase at a decreasing rate. You need more, but with each additional household member you need less more.

***

To assess how well Americans are doing today vis-à-vis their parents’ and grandparents’ standard of living, without correcting for changes in family size and structure over the past 75 years, is comparing apples and sushi. In The American Dream Is Not Dead, Michael Strain points out that Raj Chetty’s claim that half of Americans born in 1980 will end up worse off than their parents, the cornerstone of Ours Was the Shining Future’s entire argument, is a statistic that does not adjust income for declining household size. Make that correction, and the likelihood of an American born in 1980 having a higher living standard than his parents increases from 50% to 60%. Adjust for inflation by using the Personal Consumption Expenditures index, which more faithfully reflects changes in how consumers actually fend for themselves than the better known Consumer Price Index, and the likelihood increases from 60% to 67%.

According to Strain’s summary of the data Chetty published in Science magazine in 2017, Americans born from 1940 through the middle 1950s had at least a 67% chance—two out of three—to surpass their parents’ standard of living. Those odds steadily diminished over the subsequent 30 years. But Strain, Winship, and common sense all tell us that you are more likely to surpass your parents’ income if they were poor than if they were prosperous. Large numbers of those born in 1940, when the Great Depression was abating but its effects were still pervasive, “enjoyed” the “advantage” of growing up in a family that struggled to make ends meet. Normal economic growth, much less the remarkable postwar expansion, rendered earning more than your parents did highly attainable. By contrast, Americans born in the 1960s and 1970s, after a rising tide had lifted millions of boats, were quite likely to “suffer” the “disadvantage” of growing up in affluence, which set the bar for exceeding their parents’ income far higher.

It is also important to remember that technological advances and economic growth put all of us on an airport moving walkway, where standing still and making progress happen at the same time. The resulting disorientation causes us to take improvements for granted and, at the same time, leaves us more acutely aware of what we lack than of what we’ve acquired. Envying America’s mid-century prosperity disregards the difference between having three television networks available, as opposed to dozens of cable channels and streaming services, in addition to millions of websites.

***

In the same way, the wish that buying a single-family home was as easy as it seemed to be 60 years ago ignores the fact that the homes Americans were acquiring then would be considered cramped and inadequate today. “Until the 1960s,” The New York Times reported last year, “a typical single-family home built in the United States measured about 1,500 square feet.” In 2022, according to a study by LendingTree, the corresponding figure was 2,559 square feet, a 71% increase. Combine these two trends, bigger houses and smaller families, and the square feet per occupant of American houses increased 92% between 1973 and 2015, according to yet another AEI scholar, Mark J. Perry. Over those 42 years, he adds, the price of a new house has, basically, remained flat, after adjusting for both inflation and the number of people residing in it. The average price per occupant, expressed in 2015 dollars, was $116 per square foot, and the year-to-year fluctuation was in a narrow range, between $107 and $131.

This is not to say that Americans’ feelings of economic vulnerability have no basis. As Leonhardt points out, the idea that the affluent society created by the postwar economic surge could have been perpetuated endlessly “was almost certainly impossible.” The nations that suffered more serious losses than the United States during World War II eventually recovered, erasing the competitive advantages that American industries enjoyed in the 1950s. Further, capitalism’s gale of creative destruction has, through automation and outsourcing, eliminated many factory jobs that allowed workers with no more than a high school education to buy homes and send their children to college.

The effects of these market processes have been compounded by policy blunders. The “shift of production to low-wage Chinese factories,” Leonhardt says, was “one of the biggest failures of modern economic policy.” He cites a study of the “China shock,” wherein economists ascribed to it the loss of two million American jobs, disproportionately held by workers without a college degree.

***

Nonetheless, Strain argues, the overall story about the middle class’s decline has mostly been one of the upper-middle class’s steady expansion, rather than a widespread descent into poverty. Using Census Bureau data, he calculates that the share of households with incomes between $35,000 and $100,000 fell from 54% in 1967 to 42% in 2018. (His inflation adjustment expresses all income figures in terms of the dollar’s value in 2018.) But the proportion living on less than $35,000 also declined, from 36% to 28%. Thus, 20% of the population was no longer in the middle or bottom of the income distribution. That’s because it moved up: 10% of American households had an income equivalent to at least $100,000 in 1967, while 30% did in 2018.

These aggregate trends do not pay the mortgage, of course, for a family whose breadwinner was laid off after a factory closed, nor do they sustain basic municipal services in a small city that was heavily dependent on the taxes and business activity generated by that factory. Though he overstates the extent of these problems, Leonhardt is right to insist that the nation address them. To this end, he envisions a reinvigorated labor movement, one that enrolls one-third of American workers, as was the case in the middle of the 20th century. It, in turn, would be part of a broader political movement determined to “reduce corporate concentration, raise taxes on the wealthy, lower medical costs, create universal pre-K education, and increase middle-class pay.”

There are, however, good reasons to doubt the viability of this political coalition and the feasibility of this policy agenda. Writing for The New Yorker before the 2008 election, journalist George Packer interviewed Barbie Snodgrass near her residence outside Columbus, Ohio. Unmarried at the age of 42, she was working two jobs to bring home a little over $40,000 a year, the equivalent of about $57,000 today, which she used to raise two teenage nieces, her sister’s daughters. Packer asked Snodgrass about Barack Obama’s promises, quite similar to Leonhardt’s agenda, to pay for numerous enhancements to America’s social safety net entirely through tax increases on the 2% of Americans then making more than $250,000 per year. She was deeply skeptical, expressing the fear that paying for the Obama agenda would require tax increases on a much larger swath of the income distribution, ultimately including herself. “He’ll keep going down, and when it’s to people who make forty-five or fifty thousand it’s going to hit me. I’d have to sell my home and live in a five-hundred-dollar-a-month apartment with gang bangers out in my yard, and I’d be scared to death to leave my house.”

***

Since the 1960s, the New Deal coalition’s largest component has, steadily and then decisively, come to favor Republicans. In disbelief and anger, Democrats have asked why working-class Americans keep “voting against their own interests.” According to the most famous, most acerbic formulation of this lament, Thomas Frank’s What’s The Matter with Kansas? (2004), the GOP dupes gullible working-class voters into rejecting the Democratic Party, thereby thwarting social welfare policies and regulations that could enhance their economic security. Social issues are the bait that makes this con work. Performing stand-up sociology at a 2008 campaign fundraising event in San Francisco, Obama said that, in response to factories closing in small towns, the residents “get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy toward people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.”

Ms. Snodgrass made clear, however, that she does not have the luxury of considering social issues apart from economic ones. People in her circumstances get by on less than the median income while working hard and playing by the rules. Her greatest fear about a setback in her personal finances is that it would leave her unable to buy social and physical distance from dangerous and dysfunctional poor people who do not work hard and play by the rules.

A big part of the antipathy voters like Snodgrass feel for the Democratic Party arises from their belief, not unfounded, that Democrats’ default setting is to be more sympathetic to the perpetrators than to the victims of crime. After hundreds of young people engaged in mob actions in downtown Chicago last spring, resulting in two kids getting shot, a motorist beaten up, and extensive property damage, Brandon Johnson, then the city’s Democratic mayor-elect, said that such mayhem was “unacceptable,” which made it sound like a dress-code infraction. More forcefully, he admonished that it was “not constructive to demonize youth who have otherwise been starved of opportunities in their own communities.”

The spike in crime that began in the 1960s—America’s homicide rate more than doubled between 1962 and 1980, Leonhardt reports—is the chief reason why, in his words, it “was the decade when the coalition that had built democratic capitalism and allowed millions of families to achieve the American dream unraveled.” It is also the chief reason, according to sociologist Jonathan Rieder’s book Canarsie (1985), why that Brooklyn neighborhood’s middle-class residents, whom he studied in the 1970s, came to associate the Democratic Party’s liberalism with “profligacy, spinelessness, malevolence, masochism, elitism, fantasy, anarchy, idealism, softness, irresponsibility, and sanctimoniousness.”

***

Leonhardt argues convincingly that crime has harmed Democrats not only as a straightforward policy issue, but because Americans’ vulnerability to crime and disorder has set key elements of the party’s coalition against one another. He quotes “The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class,” a 1969 New York magazine article by journalist Pete Hamill. “A large reason for the growing alienation of the white working class is their belief that they are not respected,” it stated. “For now, they see a terrible unfairness in their lives, and an increasing lack of personal control over what happens to them.”

Fifty-four years later, author Chris Arnade, writing in the online journal UnHerd, found only greater unfairness on a predawn subway ride from Queens to Manhattan. His fellow passengers were of two kinds. First, roughly a dozen “overnight construction workers, office cleaners, nannies, restaurant staff, hotel employees—all coming from late shifts, or going to early shifts, carrying tool bags, hard hats, work clothes.” Second, there were four men who, asleep or passed out amid “piles of trash and puddles of urine,” had turned the subway car into one more of the city’s “mobile homeless shelters.” The former group’s preoccupation throughout the trip was to minimize the likelihood and danger of any interaction with the latter. Members of what Arnade calls the “downtown professional class,” the core of the Brahmin Left, can avoid the subway by taking Uber rides. The people like Barbie Snodgrass and the workers riding with Arnade on the subway cannot afford this measure of insulation. While the Brahmin Left are an increasingly important source of money and ideas for Democratic politicians, the subway riders grow increasingly hostile to the party and what it stands for.

Leonhardt emphasizes that Democrats cannot implement the party’s recent platforms, which track with Ours Was the Shining Future’s recommendations, until they win more elections. The road not taken, he argues, was the one Robert F. Kennedy was charting in his tragically brief 1968 presidential campaign. Kennedy was assembling “a modern version of Franklin Roosevelt’s coalition, including farmers, economic progressives, White and Black industrial workers, and immigrants and their descendants.” In Leonhardt’s telling, RFK took law and order seriously, and made clear that voters’ concerns about it were legitimate, not their way of employing a code word for racism. At the same time, his campaign was aggressively committed to economic redistribution and the expansion of the welfare state far beyond Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. One observer, Leonhardt notes, characterized Kennedy’s approach as “inclusive populism.”

***

But this account of the majority coalition Democrats could have secured but inexplicably failed to assemble sounds far more hopeful than plausible. Was there really something so esoteric about Robert Kennedy’s formula that, 56 years later, no other Democrat has been able to reproduce it? Not even Kennedy’s younger brother, Ted, who served in the Senate for another 41 years after Bobby was murdered in 1968, and whose own 1980 presidential campaign foundered precisely because of its inability to provide a compelling rationale that appealed to a majority of Democrats, much less a majority of all voters?

To believe that Robert Kennedy could have fashioned an updated version of the New Deal coalition is to believe that there were ways to placate most of the Democratic voters whose ballots produced Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 landslide—the ones who, in the party’s presidential primaries eight years later, voted for George McGovern, but also those who voted for George Wallace. The best that can be said for this notion is that it’s possible. But to speculate about the details of a President Robert Kennedy’s compromise on court-ordered busing to integrate public schools, one of the 1970s’ most divisive issues, and imagine how Kennedy could have appeased both the NAACP and the voters Jonathan Rieder came to know in Canarsie is to realize that it would have been all but impossible.

Similarly, the least secret sauce in American politics is being tough on crime. The problem is not that Democrats can’t figure out how to go about it. The problem is that, deep down, they don’t want to. Following the shock of losing five of the six presidential elections from 1968 through 1988, Democrats in the 1990s rejected social work as a substitute for police work. With Bill Clinton in the White House and Joe Biden as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, the commitment to law enforcement finally became bipartisan, crime fell dramatically…and Democrats subsequently returned to being squeamish about law enforcement. As candidates for the party’s presidential nomination, Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Joe Biden in 2020 were forced to apologize for the “harsh” rhetoric and policies of the 1990s.

***

Unable or unwilling to meet the working class halfway on social issues, Democrats’ only hope is that their agenda of redistribution and regulation will prove so successful and popular that a large subset of working-class voters will agree to disagree with the Brahmin Left about social issues, especially crime and immigration, which intersect with identity politics. Give Barbie Snodgrass union membership, better and more affordable medical care, wage enhancements, and educational opportunities for her kids, and the prospect of being forced to relocate to a tough neighborhood with gang activity will become less likely, and therefore less pressing. This is the clear political logic of, to take the most recent example, President Biden’s call to “Build Back Better”—better in the sense of policies that expand the economy “from the middle out and the bottom up.”

Whether this political bargain could work, even assuming that the material improvements were delivered, is debatable. But doubts about delivering those benefits make the whole endeavor even more unrealistic. Ours Was the Shining Future will not disabuse any reader of the belief that there is a Shared Prosperity button in the Oval Office, waiting only for a Democratic president wise and brave enough to press it. One would not know from Leonhardt’s pages that anything resembling a crisis of competence afflicts 21st-century American government. He praises high-speed rail, for example, without mentioning the 16 years and tens of billions of dollars that California has spent trying and failing to build a system between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Nor does Ours Was the Shining Future explain how government can and should pay for all the additional responsibilities Leonhardt would have it take on. He never takes exception to the promise made by Barack Obama, and every other Democratic presidential nominee since Walter Mondale in 1984, that a vast expansion of the welfare state can be financed without raising even one additional tax dollar from the least affluent 97% of the income distribution. As Barbie Snodgrass correctly deduces, that math simply does not work. Either the policy agenda will be severely curtailed, or the tax base will be radically expanded.

This disingenuous pledge also reveals a political vulnerability: calling for Scandinavian-level spending but not Scandinavian-level taxes betrays the fear that Americans who are not affluent will sign on for the maximum Democratic agenda if and only if they themselves are not assessed even a modest tax increase to pay for it. In other words, the Democratic Party acts as if middle- and working-class Americans believe the benefits they’ll receive from the party’s new and expanded social welfare programs exceed the cost they’ll incur, provided that cost is zero. But if the cost is more than negligible, then the benefits won’t be worth it. The fact that no Democrat will repeat Mondale’s promise to raise taxes, including on Americans who are not rich, argues that no Democrat can figure out how to disabuse working-class voters of their skepticism about the benefits they’ll receive from Democratic policies.

***

This question of revenue is crucial. Any argument like Leonhardt’s, about the many additional things government should be doing, cannot succeed if it does not even mention our failure to pay for all the stuff government is already doing. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), gross federal debt amounted to 124% of GDP in 2023. (It was 121% at the end of World War II, after climbing from under 20% at the start of the Great Depression, and before descending to 31% in 1980, then rising to 58% at the end of 1999. The ratio climbed above 100% in 2012, and has stayed above 100% continuously since 2015.) If “existing laws governing taxing and spending generally remain unchanged,” CBO projects that the federal debt will grow to 129% of GDP in 2033, and 192% in 2053. According to a 2023 report by the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Wharton Budget Model, 200% of GDP is the region where federal debt sets off a catastrophic, irreversible chain of events: “Under current policy, the United States has about 20 years for corrective action after which no amount of future tax increases or spending cuts could avoid the government defaulting on its debt whether explicitly or implicitly (i.e., debt monetization producing significant inflation). Unlike technical defaults where payments are merely delayed, this default would be much larger and would reverberate across the U.S. and world economies.”

Ours Was the Shining Future discusses activist government as if it faced only political constraints, keeping silent throughout about any fiscal or structural ones. David Leonhardt’s one acknowledgment that it is possible we could summon the will, yet still not find a way, is to mention in passing that “special interest groups of all types—not only those representing the wealthy—can prevent changes that would benefit society.” This is true, but more important than he allows. The closing words of the textbook American Government by political scientists John DiIulio and the late James Q. Wilson make the same point. “With the expansion of the scope of government policy,” they write, “thousands of highly specialized interests and constituencies seek above all to protect whatever benefits, intangible as well as tangible, they get from government.” As a result, “we expect more and more from government but are less and less certain that we will get it, or get it in a form and at a cost that we find acceptable.”

It is difficult, given these considerations, to take seriously the prospect of a second New Deal. After 90 years, we still have not corrected the original New Deal’s design flaws and solved its implementation challenges. Without taking on the quality of governance, including the integrity of the nation’s finances, even a smart and earnest polemic demanding that we increase the quantity of government activity is a distraction at best, and destructive at worst.