Sir Lewis Namier, the noted British historian of an earlier generation, once wrote that “when discoursing or writing about history, [people] imagine it in terms of their own experience, and when trying to gauge the future they cite supposed analogies from the past: till, by double process of repetition, they imagine the past and remember the future.” Great controversies, which often feature adversaries citing the same historical materials to opposite effect, confirm the truth of Namier’s cautionary observation. In the United States, where great controversies tend to be constitutional controversies, disagreement about our charter’s origins and meaning has been a defining feature of American political discourse from the republic’s earliest days.

After nearly 220 years, one could say that Americans have more constitutional speculation than they know what to do with—a fact readily confirmed by almost any volume of any law review, not to mention the proliferating gaggle of legal experts who fill the airwaves on cable news shows. A cynic might infer from differing scholarly opinions that debate about constitutional meaning is so much rhetorical gamesmanship. But if that is so, if politics may indeed be reduced to sophistry, why bother to have a written constitution at all?

Most Americans would reply that a written constitution is the only kind worth having. They bear a decent respect for their nation’s origins and founding documents, which they have no trouble believing were inspired by divine providence. They come by the millions every year from all over the country to the National Archives in Washington, or to the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, to gaze upon the original parchments of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. They take pride in knowing that the Constitution, which was up and running before Napoleon came to power, has survived innumerable crises, including a dreadful civil war, yet emerged largely intact.

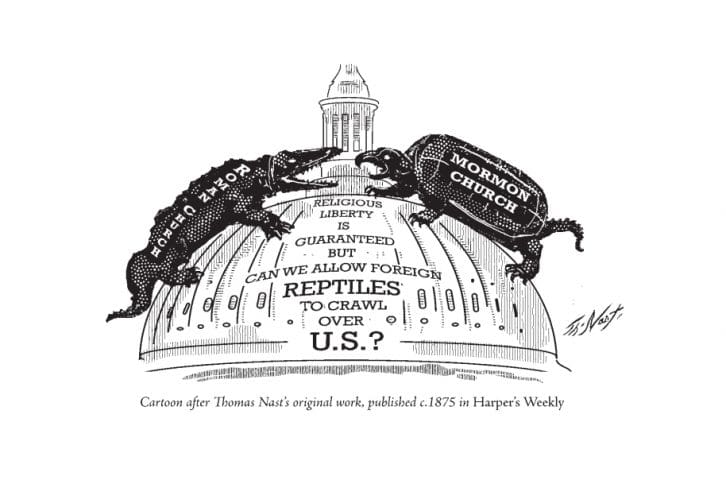

Liberals are wary of pious attachment to the past, considering it an expression of foolish sentimentality or a mask for some contemporary venal interest, but in either event as an impediment to progress. They are particularly suspicious about the framers’ motives, which they tend to explain in terms of narrow self-interest, and are dogmatically skeptical about our founding documents’ natural rights principles, dismissing them as so much wrong-headed and outmoded philosophical speculation. The resultant Constitution fares no better. It, too, is suspect for many reasons—failing to abolish slavery for one—but most of all because it sought to instantiate a regime of limited government. But, in the end, liberals care little about what the framers may have meant, for times have changed. They may object to the crudity of Henry Ford’s assertion that “history is more or less bunk,” but they do not essentially disagree with his sentiment. Liberals esteem not history, but History, which to them confirms the law of ceaseless change.

They are stuck, nevertheless, with a people reared under the aegis of a written Constitution whose authors affirmed the permanence of certain political truths. Most Americans remain stubbornly convinced that the framers got things mostly right on government’s basic principles. From the Progressive movement’s early days until the present hour, the liberals’ medicine for this notable lack of popular enlightenment has consisted in one long effort to deconstruct the founding. The permanence of the Declaration’s truths is denied; the framers’ inability or refusal to resolve the issue of slavery is attributed to moral hypocrisy; the architecture of the Constitution is read as a series of mischievous devices to frustrate majority rule or to protect the ruling class’s interests. These and similar critiques, which by gradual degrees have worked their way into standard textbooks and school curricula, have taken their toll on patriotic sentiment.

Old habits, however, die hard, which helps to explain the intellectual chaos of contemporary constitutional debate. Respect for the founding principles, though wounded, refuses to die; the new dispensation, though powerful, has yet to triumph. Whatever else may have accrued from the effort to deconstruct the founding, this much seems clear: the once common ground of constitutional discourse has fallen away. Witness the current debate between originalists and proponents of the “living” Constitution: they disagree about the meaning of constitutional wording, to be sure; but their deepest disagreement has to do with whether and why 18th-century words and concepts should now matter at all.

What Wilson Wrought

The outcome of this debate has yet to be determined, but it has produced a number of notable anomalies, particularly with respect to the separation of powers. Ever since Woodrow Wilson set pen to paper, liberals have expressed frustration with, if not outright scorn for, the separation of powers. They read it almost exclusively in terms of its checking-and-balancing function, i.e., as a barrier that for many decades prevented the national government from enacting progressive social and economic policies. The other half of James Madison’s elegant argument for separating powers—energizing government through the clash of rival and opposite ambitions—seems to have escaped their attention altogether, as has the framers’ understanding that government powers differ not only in degree, but in kind. Transfixed by their own deconstruction of the founding as an effort to frustrate popular majorities, liberals find it hard to believe that the framers could have imagined the need for powerful government or a powerful chief executive. Indeed, a dominant theme of early Progressive thought—one still widely shared today—advanced the notion that the Constitution meant to enshrine legislative primacy. Accordingly, energetic presidents prior to the modern era are seen as exceptions that prove the rule, their boldness being variously attributed to the peculiarities of personality, short-term aberrational events, or national emergencies such as the Civil War—to everything, in short, except the intended purpose of Article II of the Constitution. It was only after decades of struggle, so the argument continues, that a new constitutional order, with the president as its driving force, came to ultimate fruition in the New Deal.

This reading of the founding and of American political history has a surface plausibility, fed in no small part by the republican Whig rhetoric that was so fashionable in much early American discourse. Upon closer examination, however, it turns out that congressional dominance is not the only story that emerges from 19th-century political history. As a large and growing body of thoughtful revisionist inquiry has demonstrated, that history is no less the story of effective presidential leadership that drew upon Article II’s deliberately capacious language. Notwithstanding, contemporary liberal doctrine remains deeply indebted to the original Progressive indictment of the founding, and especially to Woodrow Wilson’s thought, which remains the philosophical wellspring of almost every constitutional prescription in the liberal pharmacopoeia.

After flirting with the idea of grafting a parliamentary system onto the American constitutional structure, Wilson made a virtue of necessity by reconceiving the Office of the President. The nation’s chief executive would defeat the original Constitution’s structural obstacles by, so to speak, rising above them. Wilson’s chosen instrument for this purpose was party government, which would breach the parchment barriers dividing president and Congress and unite both through a common policy agenda initiated by the president. The president would make the case for policy innovation directly to the people. Once armed with plebiscitary legitimacy, he might more easily prod an otherwise parochial Congress to address national needs. Madisonian fears about the mischiefs of faction would be overcome by separating politics and administration: Congress and the president would jointly settle upon the desired policy agenda, but its details, both in design and execution, would rely on non-partisan expert administrators’ special insight and technical skill, operating under the president’s general direction and control.

The presidency, thus reconceived, would by turns become a voice for and dominant instrument of a reconceived Constitution, which would at last detach itself from a foolish preoccupation with limited government. The old Constitution’s formal structure would be retained, insofar as that might be politically necessary; but it would be essentially emptied of its prior substantive content. In Wilson’s view, the growth of executive power would parallel the growth of government in general. The president would no longer be seen as, at best, Congress’s co-equal or, at worst, the legislature’s frustrated servant. Henceforth, he would be seen as proactive government’s innovator-in-chief, one who was best positioned to understand historical tendencies and to unite them with popular yearnings. In an almost mystical sense, the president would embody the will of the people, becoming both a prophet and steward of a new kind of egalitarian Manifest Destiny at home and, in the fullness of time, perhaps throughout the world.

Unintended Consequences

The result of Wilson’s vision is the administrative state we know today. Although it has retained the original Constitution’s structural appearances, the new order has profoundly altered its substance—though not precisely in the way that Wilson intended, as we shall see. The arguments that once supported the ideas of federalism and limited government have fallen into desuetude: state power today is exercised largely at the national government’s sufferance, and if there is a subject or activity now beyond federal reach, one would be hard-pressed to say what it might be. As for the separation of powers, while the branches remain institutionally separate, the lines between legislative, executive, and judicial power have become increasingly blurred. The idea that government power ought to be differentiated according to function has given way to the concept that power is more or less fungible. The dominant understanding of separated powers today—see the late Richard Neustadt’s widely accepted argument in Presidential Power (1960)—is that the branches of government compete with one another for market share.

While most liberals continue to celebrate the old order’s decline, the more thoughtful among them have expressed reservations of late about certain consequences of the Wilsonian revolution. It is widely remarked in the scholarly literature on the presidency, for example, that we have come to expect almost impossible things of modern presidents, and that presidents in turn come to office with almost impossible agendas to match heightened public expectations. After many decades of living with the modern presidency, it can be argued that the effort to rise above the separation of powers has only exposed presidents the more to the unmediated whimsies of public opinion. Far from being masters of all they survey, modern presidents are pulled this way and that by factional demands generated by an administrative state over which they exercise nominal but very little actual control.

The presidency’s transformation has radically altered our system of government, but it poses a particular problem for liberals. The difficulty begins in their appetite for big government. Indeed, liberals can identify enough unmet needs, unfulfilled hopes, and frustrated dreams to satisfy the federal government’s redistributionist and regulatory ambitions as far into the future as the eye can see. An already large and unwieldy federal establishment, expanding to meet the rising expectations of an ever more demanding and dependent public, threatens to become yet larger, more powerful, and harder to control. But, despite what bureaucrats might wish to believe about the beneficial effects of their expertise, the administrative state is not a machine that can run itself. It requires coherent policy direction; it needs to be managed with reasonable efficiency; and it has to be held politically accountable. As a practical matter, only a president can do these things, but with rare exceptions, presidents are prevented, mainly by Congress but also by the judiciary, from performing any of these tasks well.

It is here that a bastardized version of the separation of powers remains alive and well. The short history of the administrative state since at least the New Deal is a tale of protracted conflict between Congress and the president for control of its ever-expanding machinery. After initial resistance, which remained formidable until roughly 40 years ago, Congress has finally learned to love big government as much as, if not more than, presidents do. As political scientist Morris Fiorina has shown, Congress loves it because it pays handsome political returns. The returns come from greasing the wheels of the federal establishment to deliver an increasing array of goods and services to constituents and interest groups, who reward congressional intervention with campaign contributions and other forms of electoral support. Such political benefit as may accrue from enacting carefully crafted legislation is much less, which is why legislators devote far more time to pleasing constituents and lobbyists than they do to deliberating about the details of laws they enact. Congress is generally content to delegate these details, which often carry great policy significance, to departments and agencies, whose actions and policy judgments can forever after be second-guessed by means of legislative “oversight.”

The New Spoils System

Indeed, Congressmen have become extraordinarily adept at badgering this agency or that program administrator for special favors—or for failing to carry out “the will of Congress.” In most cases this means the will of a particular representative who sits on the agency’s authorization or appropriations committee, and who has been importuned by a politically relevant interest group to complain about some bureaucratic excess or failure. Modern congressional oversight has become an elaborate and sophisticated version of the old spoils system adapted to the machinery of the administrative state. When it comes to currying favors, Congressmen know how to home in on programs under their committee’s jurisdiction to extract what they want in terms of policy direction or special treatment, and there is enough boodle in a nearly $3 trillion federal budget to satisfy even the most rapacious pork-barreler. Likewise, when it comes to bashing bureaucrats, Congressmen have little trouble identifying vulnerable targets of opportunity. The federal government is so large, and its administrators so busy trying to execute often conflicting or ambiguous congressional instructions, that Congress can, like Little Jack Horner, stick in its thumb and pull out a plum almost at random. The modern oversight investigation, which has less to do with substance than with conducting a dog-and-pony show for the benefit of a scandal-hungry media, has become a staple of the contemporary administrative state. And it almost always redounds to Congress’s political benefit, for the simple reason that the exercise carries little if any downside risk. But political theater of this sort, however profitable it may be to particular representatives, is a far cry from the deliberative function that the framers hoped would be the defining characteristic of the legislative process.

It is an open question, to be sure, whether anything so large as the current federal establishment can be reasonably managed, and it is something of a miracle that it works at all. Even so, Congress would do itself and the nation an enormous favor if it devoted more time to perfecting the legislative art, which includes paying serious attention to the policy coherence and consequences of its delegated legislative authority. In general, however, Congress has little political motive or (given its internal dispersal of power to committees and subcommittees) institutional capacity for substantive evaluation of the many programs it enacts and ostensibly oversees. It complains endlessly about the administrative state’s inefficiency and arbitrariness, but compounds the problem by creating new agencies and programs in response to political urgencies. As it does so, it takes care to protect its own prerogatives even as it denies to the executive the requisite authority to control the administrative system.

This reluctance to vest the president with control has sometimes expressed itself in the form of independent agencies (independent, that is, of the president), which mock the idea of separated powers by vesting legislative, executive, and judicial functions in the same institution. Consider Boston University law professor Gary Lawson’s provocatively compelling description of the Federal Trade Commission, which typifies the workings of the system as a whole:

The Commission promulgates substantive rules of conduct. The Commission then considers whether to authorize investigations into whether the Commission’s rules have been violated. If the Commission authorizes an investigation, the investigation is conducted by the Commission, which reports its findings to the Commission. If the Commission thinks that the Commission’s findings warrant an enforcement action, the Commission issues a complaint. The Commission’s complaint that a Commission rule has been violated is then prosecuted by the Commission and adjudicated by the Commission. This Commission adjudication can either take place before the full Commission or before a semi-autonomous Commission administrative law judge. If the Commission chooses to adjudicate before an administrative law judge rather than before the Commission and the decision is adverse to the Commission, the Commission can appeal to the Commission. If the Commission ultimately finds a violation, then, and only then, the affected private party can appeal to an Article III court. But the agency decision, even before the bona fide Article III tribunal, possesses a very strong presumption of correctness on matters both of fact and of law.

This pattern has become an accepted feature of the modern administrative state, so much so that, as Lawson notes, it scarcely raises eyebrows. Presidents and Congress long ago accommodated themselves to its political exigencies, as has the Supreme Court, which since the 1930s has never come close to questioning independent agencies’ constitutional propriety.

Raiding Executive Authority

When dealing with the executive branch as such, Congress frequently delegates and retains legislative authority at the same time. It does so, inter alia, through burdensome or unconstitutional restrictions on the exercise of presidential discretion, which it inserts in authorizing legislation, appropriations bills, or, sometimes, even in committee report language. It has also contrived a host of other devices to hamper executive control. For many decades, for example, it indulged broad delegations (e.g., “The Secretary shall have authority to issue such regulations as may be necessary to carry out the purposes of this Act”), but as the number of agencies expanded and as delegated regulatory authority began to bite influential constituencies, Congress responded by imposing (variously) two-House, one-House, or in some cases even committee vetoes over agency action. Although the Supreme Court declared most legislative vetoes to be unconstitutional in INS v. Chadha (1983), Congress has improvised additional measures to second-guess the operations of the executive branch.

Confirmation hearings in the Senate, for example, are increasingly used to extract important policy concessions from prospective executive appointees, who learn very quickly that while the president is their nominal boss, Congress expects to be placated and, failing that, knows how to make their lives miserable. To underscore this point, in addition to the omnipresent threat of oversight hearings, Congress has enacted extensive “whistle-blower” legislation and created inspector-general offices for every department and agency, which operate as semi-demi-hemi-quasi-independent congressional envoys within the executive branch. For a time (until Bill Clinton got caught in the web), Congress was also enamored of special counsels, empowering them by legislation to investigate and prosecute alleged executive malfeasance, and at the same time ensuring that their activities were not only beyond the president’s authority to control, but beyond the Congress’s and the courts’ as well. (Demonstrating that the separation of powers in our time is more honored in the breach than the observance, the Supreme Court sustained the legislation with only one dissent.)

One may say by way of summary that Congress has, without fully realizing it, succumbed to Wilson’s plan to eviscerate the separation of powers. It has failed to realize it in part because the administrative state’s growth has occurred gradually; in part because it has learned how to profit politically by the change; and in part because it has convinced itself that conducting guerilla raids against executive authority is the most beneficial expression of the legislative function.

Taming the Administrative State

Presidents have chafed under congressional controls, rightly complaining that they interfere both with their constitutional powers and their ability to make the administrative state reasonably efficient and politically accountable. They have responded with various bureaucratic and legal weapons of their own. These include a greatly expanded Executive Office of the President (in effect, a bureaucracy that seeks to impose policy direction and managerial control over other executive bureaucracies), a massive surge in the use of executive orders, and increasing reliance on signing statements reserving the president’s right not to enforce legislation he considers to be unconstitutional. Ever since the New Deal, and growing proportionately with the size of the federal establishment, a good deal of White House energy has been devoted to trying to manage and direct the administrative state—and to reminding Congress in diverse ways that the Constitution provides for only one chief executive. But modern presidents, like the modern Congress, have also succumbed to the lure of Wilson’s theory concerning the separation of powers. They clearly enjoy the prospect of becoming the principal focal point for national policy, but once in office soon discover that the mantle of plebiscitary leadership can be assumed only at great cost. Unlike Congress, presidents remain politically and legally accountable for the administrative state’s behavior. In order to execute their office as their constitutional oath demands, they must pay serious attention to the separation of powers in ways that Congress does not.

Presidents sometimes win and sometimes lose in their struggles with Congress, but each new contest only serves to compound the constitutional muddle that now surrounds the separation of powers, a muddle made all the more confusing by the Supreme Court’s Janus-faced rulings in major cases, which also bear the mark of the political revolution launched by Wilson’s indictment of the structural Constitution. On a practical level, presidents have only modest gains to show for their continuing efforts to manage big government. Overall, when it comes to controlling the administrative state, the operative slogan might well be “Congress Won’t and the President Can’t.” So much for Wilson’s vision of the rational ordering of public policy through neutral expertise under the benign guidance of inspired presidents working in cooperation with Congress. Wilson dealt the separation of powers a mortal blow without understanding the full implications of what he had wrought. Without a vigorously enforced, reasonably bright-line distinction between the kinds of powers exercised by the different branches, the very presidency he hoped to create has been frustrated in its ability to execute coherent policy, or to manage those charged with fleshing out its details. For its part, Congress as a whole is even less interested today in deliberating about the coherence of national policy than it was when Wilson inveighed against its parochialism and committee structure in the late 19th century. And, it may be added, with each passing year the administrative state whose birth Wilson midwifed becomes increasingly harder for any of the branches, jointly or severally, to control.

Having it Both Ways

Liberals are not particularly happy with the present state of affairs, but their enthusiasm for big government leaves them little choice but to support expansive presidential authority; it is the only available instrument capable of seeing to it that their desired social reforms are carried out. They encourage Congress to create or expand progressive programs, and generally applaud congressional bashing of bureaucrats (especially when the targets come from the opposite end of the political spectrum); but they do not otherwise wish to see Congress heavily involved in the business of directing public administration, for they rightly suspect that when Congress does so, the likely beneficiary will be some private interest rather than the public good. As for presidential direction and control of policy, liberals tend to favor executive discretion when Democrats occupy the Oval Office, but are generally dubious about it when exercised by Republican incumbents. Like Al Gore, they’re in favor of reinventing government so long as it doesn’t disestablish or interfere with favored agencies or programs.

Liberals, in short, will complain about the administrative state’s inefficiency and unwieldiness, and while they would no doubt like it to work better they haven’t a clue about how to reform it—other than by tinkering with its machinery at the margins. In truth, liberals have no desire for systemic change. They do not wish to reduce government’s scope; and they certainly do not wish to revive the old Constitution’s structural distinctions that separate the branches of government by function, for that, too, might diminish or eliminate many of the cherished programs they spent so many decades creating. The era of big government may be over, but only in Bill Clinton’s rhetoric; big government itself is here to stay, as is the constitutional confusion that surrounds the separation of powers and threatens to extinguish its purposes altogether.

Although liberals generally applaud the demise of 18th-century constitutional strictures when it comes to domestic policy, they are not above extolling the old Constitution’s virtues in foreign and national security affairs. The late Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., surely the model of 20th-century high-toned liberal sentiment if ever there was one, raised the execution of this intellectual two-step to a fine art form. He began his scholarly career by discovering in Andrew Jackson’s administration a pre-incarnation of Franklin Roosevelt’s plebiscitary presidency. Later, in his multi-volume hagiography of the New Deal, he defended the expansion of unfettered executive discretion in domestic affairs as a necessary concomitant of the burgeoning administrative state. In foreign affairs as well, Schlesinger praised FDR’s aggressive use of executive power, not only during World War II (which is understandable enough), but also in the pre-war years (which is more debatable). Schlesinger took a similar tack in his praise of John F. Kennedy, who in Schlesinger’s eyes was a kind of reincarnation of FDR. Then came Vietnam, Watergate, and the assorted excesses of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, as a result of which the presidential powers Schlesinger had previously celebrated suddenly became harbingers of imperial pretension. The imperial presidency motif disappeared once Jimmy Carter came into office, only to resurface periodically and vociferously during the Reagan years. It disappeared yet again while Bill Clinton held the office, and reappeared like clockwork in criticism of George W. Bush’s anti-terrorism policies.

Schlesinger’s personal tergiversations to the side, his ambivalence about executive power is a perfect measure of the modern liberals’ dilemma: they want a chief executive capaciously adorned with constitutional discretion when it comes to pushing government to carry out their social and economic agenda, but sound constitutional alarms when their own theory of presidential power gets applied to the execution of foreign and national security policies they do not like. That constitutional theory is sometimes bent to short-term policy preferences is hardly novel or shocking. But there is a deeper constitutional problem here as well, arising from liberals’ embrace of Wilsonian theory. One simply can’t have it both ways when it comes to the Constitution’s grant of executive power—a small presidency for foreign affairs, but a large one for domestic affairs. If anything, a stronger case can be made the other way around: the vesting clause, the take-care clause, and the oath of office are common to both cases, but in war-related matters the president has an additional claim of authority stemming from his powers as commander in chief.

Conservatism and Executive Power

Not so long ago, conservatives might have been accused of harboring a similar inconsistency. For a long time, they were deeply suspicious of the executive branch, correctly seeing in its growth the dangers that flowed inexorably from the Wilsonian revolution in political thought—a notable increase in presidential caprice and demagogy, and a notable increase as well in the government’s size, driven by the engine of the plebiscitary presidency. The memory of FDR’s arguable abuses of executive power remained deeply etched in the conservative memory for the better part of three decades. Well into the 1960s conservatives remained congressional partisans, having bought into the academic consensus—ironically, a consensus Wilson also helped to create—that the Constitution meant to establish legislative dominance. There was a second, more immediate, ideological reason: Congress, precisely because it represented a federated nation in all its diversity and complexity, was less likely to embrace utopian liberal schemes or an expansive federal establishment. Willmoore Kendall, the resident political theorist at National Review in its early days, was justly famous for his 1960 essay on “The Two Majorities,” the central argument of which was (a) that a regime of presidential supremacy was not the government America’s framers fought for; and (b) that Congress, in its geographically and culturally distributed collectivity, was a better and more legitimate expression of democratic sentiment than could be found in the modern plebiscitary presidency. (Kendall was at least half-right. His essay is in any event a remarkable exercise in good old-fashioned political science, published before the behaviorists took hold of the profession. Warts and all, it remains an engrossing and rewarding read.)

In the year before Kendall’s essay appeared, James Burnham, another important National Review editor with impressive academic credentials, published Congress and the American Tradition, an extended paean to the framers’ wisdom in elevating congressional power to preeminence. Burnham’s argument, like Kendall’s, was designed in part to encourage Congress to become more aggressive in checking what Burnham saw as a dangerous trend toward executive self-aggrandizement and arbitrariness. The book, however, was as much a lament as a prescription for reform, for even as he wrote Burnham feared that Congress had already lost its edge as a countervailing force against the exponential growth of government in general and executive power in particular.

Nowadays, of course, National Review and most conservatives have become strong supporters of unitary executive powers, particularly in foreign and national security policy. The change appears to have begun during the late 1960s, when the execution of the Cold War took a bad turn in Vietnam. Conservatives certainly had no love for Lyndon Johnson or anything resembling his Great Society, but they realized that a vigorous executive, armed with as much discretion as could decently be allowed, was essential to keeping the Communists at bay. Congress, hitherto the collective repository of conservative wisdom (including quasi-isolationist tendencies), could no longer be counted on to defend the West. The Kendall-Burnham argument lost favor.

Such reservations as conservatives once had about presidential power on the domestic front became decidedly secondary to the overarching goal of deflating the Communist threat. For the most part, those reservations have not been reasserted, but not because conservatives came to embrace Wilson’s general theory of history or of the state; rather, conservatives reluctantly resigned themselves to the fact that the administrative state is more or less here to stay. They would prefer, of course, smaller government, but as long as big government remains the order of the day, conservatives argue that the only way to make it reasonably efficient and politically accountable is to vest the president with sufficient authority to run it. On the conservative side, then, there is a rough symmetry between their position regarding presidential power at home and abroad.

War Measures

Not everyone on the right shares this disposition, and President Bush’s mismanagement of the Global War on Terror (if that’s what the administration still calls it) has prompted some conservative thinkers to revisit the arguments advanced by Kendall and Burnham and to reassert the case for congressional authority over war-making. In this, they have plenty of company from liberals, who are dusting off their copies of Anti-Federalist tracts, Max Farrand’s Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, and other primary source material on the framers’ and ratifiers’ intent.

But letting go of Kendall and Burnham is a lot easier for most conservatives than letting go of Wilson is for liberals. Much of the activity of the political science profession, as well as of the history profession, rests on the philosophical and political premises that made Woodrow Wilson famous and to which he devoted so much of his academic life. One takes a certain perverse pleasure these days in watching liberals wrap themselves in the arguments of James Madison (or at least the Madison who, in 1793, argued for the executive’s limited role in foreign policy). One suspects they will not go much further into Madison’s political thought than is necessary to bash George W. Bush or anyone else who supports expanded executive power in the war on terrorism—especially the “surge” in Iraq, military trials for the enemy combatants housed in Guantanamo, and the use of NSA intercepts. The Madison of 1793, and others from the republic’s early days who were suspicious of executive authority, have their uses to Bush’s opponents at the present hour, but liberals will not wish to carry their arguments so far as to undercut Wilson’s justification for the modern presidency or his general indictment of the old Constitution’s principles and structure: the entire liberal enterprise depends on holding on to that sacred Wilsonian bastion.