Three days before his sweeping victory this fall, Donald Trump promised a crowd in Salem, Virginia that Election Day 2024 would be the most important day in the history of our country. What are we to make of that statement? On the one hand, it’s nonsense: Had this year’s election taken place in April 1865, it might not even have qualified as runner-up for most important day of the week. On the other hand, this Election Day did wind up capping an extraordinary political comeback, not to mention an uprising. The consequences could well be vast.

Everyone who listens to Trump understands that his oratory is hyperbolic. In a technocratic age, certain Americans have grown so unused to hyperbole that they consider it a form of lying, and hate Trump for it. Others look at hyperbole as the only way of breaking through a carapace of official propaganda to tell the truth about problems, and love him for it. Who is right? As a philosophical matter, that’s a long discussion. As a practical matter, our election has resolved the question, as elections do.

Trump’s oratory won him the election. But it has not won him a reputation as any kind of Great Communicator. That’s because his communications style is new, and still evolving. It’s different than it was in 2016 and even 2020. True, Trump can excel at those powerful, parallelism-filled exhortations familiar from every presidential campaign since the founding. “We will not be invaded, we will not be occupied, we will not be overrun, we will not be conquered!” he told the crowd in Salem. “We will be a free and proud nation once again. Everyone will prosper. Every family will thrive.” Plenty of presidential candidates—from Harry Truman to Ted Kennedy to Elizabeth Warren—have campaigned in that register.

But the heart of Trump’s communications style has always lain elsewhere. At 78, he still gives marathon speeches, averaging almost 90 minutes apiece. By the end of the campaign he was giving three a day, often in cities hours apart by plane—a feat of stamina that might drive a politician half his age into a delirium. Although not quite unprecedented, they are unlike anything politicians have ventured since the 19th century, when Charles Sumner would hold the Senate floor for two days or Daniel O’Connell would gather much of Ireland at one of his monster meetings.

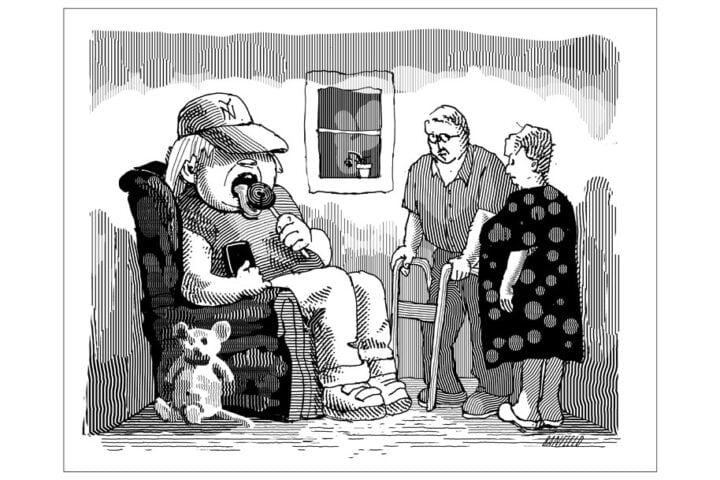

But Trump’s speeches are different. They’re more like happenings. His crowds aren’t coming to be steered in the right direction or forged into a common will. They have mixed motives. Some come to laugh, some come to rage, and some come to participate in a bacchanal. Trump creates an environment of freedom. You might call it a safe space. What his technocratic opponents deplore as crudity and braggadocio, his defenders consider a display of openness and authenticity, a radical kind of honesty, even an intimacy. Of course, both views are correct. Trump is about to change American life because he reflects American life. This became clear in the closing stage of the campaign.

Doggerel

The only presidential debate between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris took place on September 10. The date had been proposed by Joe Biden’s campaign as the last of two debates. The senescent Biden was expected to perform dismally in both, and the absurdly early finish to debating season was meant to provide the public ample time to forget them. But in the first debate, held June 27 (see William Voegeli’s “All the President’s Mental Lapses” in this issue), Biden fell so far short of low expectations that his party began a panicked effort to replace him. At the second debate, Biden was gone and Harris turned the tables on Trump. There had never been a more thorough drubbing. Harris—sunny, composed, precisely on point—spent 90 minutes reeling off impassioned oratory while Trump groused at the hostile moderators. Every answer was like the beginning of one of his rally speeches, except that he would get cut off just as it was getting interesting. He kept giving the same answers. Ten minutes into the debate he was out of material.

Within a few days, though, the public’s memory of the contest had been strangely transformed. Hardly anyone remembered the limpid but, in retrospect, empty phrases that Harris uttered. (“I say: We don’t have to go back. Let’s not go back. We’re not going back. It’s time to turn the page. And if that was a bridge too far, then there is a place in our campaign for you.”) Everyone remembered instead what happened when Harris belittled Trump’s rallies, and Trump—as pundits put it at the time—“took the bait.” “She can’t talk about that,” he said. “People don’t leave my rallies. We have the biggest rallies, the most incredible rallies in the history of politics. That is because people want to take their country back.” And then he started rolling. He began talking about the country being on the verge of World War III. He began talking about the terrible things that waves of migration were doing to small towns. And then he mentioned the city of Springfield, Ohio, where at least 10,000 Haitians had settled, driving up rents and alarming the locals with their unusual folkways. “In Springfield,” Trump said, “they’re eating the dogs, the people that came in. They’re eating the cats. They’re eating the pets of the people that live there.”

Now we were in Trump country! His claim was contested, but not baseless. There had been police calls in other towns in Ohio. There had been arrests for similar crimes. There had been reports about Springfield on television, as Trump noted. On the split screen, Kamala Harris rolled her eyes. The moderator, David Muir, insisted—twice—that the city manager of Springfield had denied significant pet-eating in his jurisdiction, as if the disagreement of an interested party were a factual refutation. Most newspapers adopted the same position when they put video of the debate online the following day: “‘They’re Eating the Dogs’: Trump Makes False Claim About Migrants,” wrote The Wall Street Journal; “Trump amplifies false racist rumor against Ohio’s Haitian immigrants in debate” is how PBS put it.

Months later, there cannot be a shred of doubt that the debate helped Trump. That is another way of saying he won it. He won a debate that close to 100% of those who saw it thought he had lost. Its most important result was to impart to more fortunate Americans a sense of the havoc illegal immigration was wreaking on the country’s small towns. This was happening elsewhere, too: in Logansport, Indiana, for example, which saw a similar Haitian influx; or in Lockland, Ohio, where 3,400 residents had lately been joined by 3,000 Mauritanians. Whether dogs were being eaten was secondary. The havoc was primary. Trump cared about it. Most people in authority couldn’t have cared less, and Harris, guffawing on the split screen, showed herself to be one of these.

Even when he is not telling an actual man-bites-dog story, Trump has a gift for making things vivid. His language has a strange, percussive beauty to it. People who love English often remark that it is a Germanic language with, ever since the Norman Conquest, a vast store of words from the Romance languages. Crude, everyday objects have tended to keep their Germanic names, while ideas and ideologies and newfangled abstractions get introduced into the language in their Romance form. A good English prose style is generally considered to be a matter of balancing the two. But Trump is not like that. He has rightly been called materialistic, in the sense that he cares about things. His speeches concern stuff. They are therefore full of blunt Germanic words. The only Latin word in his diatribe about Springfield was “people,” and that’s a pretty down-to-earth word. Trump didn’t say “the metropolitan area” or “the population” or “the community.” No, he said, “the people that live there.” Trump tends to use Latinate words when he is mimicking or belittling technocrats, and he squeezes them into a nerdy, nasal “Poindexter” voice, as when he imitated the Harris campaign spokesmen who accused him of being “cognitively impaired.”

Trump talks in a raw kind of tempo that goes well with music. The day after the debate, a South African musician called The Kifness turned the dogs and cats remark into a song. A week after that, when The Kifness was touring in Germany, a Cologne audience already knew the song well enough to sing along to it. At a late-campaign rally in Traverse City, Michigan, Trump mocked Harris for seeking celebrity endorsements instead of the votes of regular Americans. “Kamala Harris is at a dance party with Beyoncé,” Trump said. Within hours a dance mix of “Dance Party with Beyoncé” featuring Trump’s voice could be found on YouTube.

Suddenly the truth about a lot of matters elites meant to cover up was being revealed, by the power of art, by the power of crafting stories, to use the expression of Trump’s running mate J.D. Vance. Crafting stories did not mean “making things up,” as Vance’s detractors claimed. It meant cutting through the noise. It was like what the German immigration foe Frauke Petry said when asked to explain why her party had grown more confrontational during the European migration crisis of 2015. “We tried very hard at the beginning of 2013 to be heard with lots of very sensible thinking and arguments,” Petry explained, “and we simply couldn’t get through to anyone. So, what do you do? You put forward a provocative argument, and sometimes you are given the chance to explain what you meant.”

Dissident Art

What was going on in the Trump campaign was a kind of dissident art—and it thrilled people in the half-aesthetic, half-liberationist way dissident art does, imparting a rebel energy to everything they did. The Québécois journalist Mathieu Bock-Côté has pointed out that one of the unintended consequences of Democrats’ post-January 6 strategy of calling Republicans “insurrectionists” is that it turned the party leveling the accusation into the Establishment. Seen alongside its opponents, the Trump campaign was incomparably cooler. Grandmothers danced on TikTok videos captioned: “Here’s how it feels to be voting for a convicted felon.” You could see “Felon-Hillbilly 2024” T-shirts in the arenas Trump filled with his speeches night after night.

Trump brought speakers who were actually interesting to listen to, people like Elon Musk and Tucker Carlson. “I saw the Grateful Dead in this arena in 1987,” said Carlson when he spoke at Trump’s Madison Square Garden rally a week before Election Day. “How weird.” But Carlson was making a wry joke: it actually wasn’t weird. The atmosphere was kind of like a Dead concert. Trump began lingering after his talks and just listening to music, dancing to it. This kind of thing had never happened on a presidential campaign before, although there had been elements of it in Robert F. Kennedy’s brief campaign in 1968—a candidate was really, genuinely hanging out with his voters. And it made an asset out of something that had until recently seemed scary, autistic, and disadvantageous: Trump’s inability to compartmentalize his personality, the apparent lack of distinction between his public self and his private.

There’s nothing stupider than the assumption that political campaigns are mostly clashes between the candidates’ positions on “the issues.” Campaigns are just as much about getting to know the candidate, to see if he’s a person you trust to make decisions, whether because he won’t panic in a crisis or because he’s someone who resembles you. Trump has never made this kind of explicit pitch based on character—but the country was getting to know him with a thrilling kind of intimacy. Thanks to cellphones and TikTok, it now carried him around in its shirt pocket or jeans pocket. Whether or not these people keep their bond to Trump and to each other is going to determine a lot about the future of American politics.

That is why the incident at the margins of the Madison Square Garden rally, when a comedian named Tony Hinchcliffe called Puerto Rico “a floating island of garbage,” actually was a crisis for the Trump campaign. As Alexis de Tocqueville noted, Americans are an emulative people. They like being considered rebels but don’t like being considered losers. Since the onset of the Trump movement, Democrats have tried to damage the brand by insisting, with some success, that only “deplorables” vote Republican. Over time their strategy grew stale with repetition, producing a pro-Republican backlash. But if Republicans showed themselves to be losers, the whole Tocquevillian dynamic might come back into play. That was the problem with the Hinchcliffe routine—not the part about Puerto Ricans (which didn’t even seem to bother Puerto Ricans) but the flourishes of envious sexual vulgarity that surrounded them. It was not that the comic made Republicans look like a bunch of bigots. It’s that he made them look like a bunch of incels. The spell was nearly broken.

It was Joe Biden who rescued Republicans, if inadvertently. While Harris made her closing pitch to voters on the White House Ellipse, the president managed to log on to a Zoom call during a Silver Alert moment. “I don’t know the Puerto Rican that I know,” he said in some confusion. “Or Puerto Rico where I’m in my home state of Delaware. They’re good, decent, honorable people. The only garbage I see floatin’ out there is his supporters.” And with that, he set the stage for another eccentric but highly effective Trumpian oration.

Trump showed up in Green Bay, Wisconsin the following night wearing a reflective orange vest he said was a garbageman’s outfit. Trump didn’t carp at Biden. Instead, with a subtlety that Yogi Berra would envy, Trump told a shaggy dog story about how his campaign advisors were trying to convince him to exploit Biden’s gaffe by filming a campaign appearance in a garbage truck. It was another one of those paradoxical Trumpian campaign moments: what better way for a rebel to reveal the hollowness of American campaign rhetoric than to invite the audience behind the scenes to show them how his own campaign manufactured photo ops in hopes of luring in voters? Trump had done this before. At the Al Smith dinner in New York several days before, he had blamed the crudity of some of his jokes on the speechwriters who wrote them for him. Normal politicians don’t ever reveal that they’re just parroting words others have written, any more than normal anchormen do. You would think that this kind of “postmodern” or “subversive” “deconstruction” of campaigning tactics would thrill some of the progressive academics who often deride Trump. But it doesn’t. With a couple of exceptions (conspicuous among them the longtime political reporter Joe Klein), Trump’s detractors have found it impossible to understand this part of his appeal. For all his inaccuracy and exaggeration, Trump’s supporters find him authentic and sincere—perhaps the only authentic and sincere politician they have ever seen.

The wounding of Trump by a sniper’s bullet in Butler, Pennsylvania in July had deepened this understanding of him, to put it mildly. Voters, sympathetic and unsympathetic, saw him in all his intimate vulnerability. The event was shocking—in fact, only a few millimeters separated it from being the most shocking thing ever witnessed on a screen since the invention of moving pictures more than a century ago. A series of pops. Trump touching his head with his fingertips. Blood on them. Trump falling. Trump on the ground, surrounded by secret service agents for about a minute. Trump rising. Trump punching his fist in the air and hollering, “Fight, fight, fight.” Before the word fell into overuse as a synonym for “famous,” this series of images might have been called “iconic.” It retains an almost religious power. In the days after the episode, Trump mentioned it only to place it in such a context, by saying he thought God had turned his head away. Thereafter, he milked it occasionally, but he was in general less boastful about surviving a bullet to the head from a high-powered rifle than Biden had been in 2020 about standing up to a bully named Corn Pop at a poolside in Wilmington, Delaware during the Eisenhower Administration.

After deploring violence, the Biden campaign didn’t speak of the assassination attempt. There was a magic about the moment they were disinclined to awaken. You’re either the kind of guy who, after he’s shot, stands up and pumps his fist, or you’re the kind who doesn’t—and rare is the man who gets the chance to show which of the two he is. Mark Zuckerberg called it “one of the most bad-ass things I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Trump Is for You

Biden had never been a good speaker, but age had debilitated him. He could speak convincingly in only one register: anger. It’s only in anger that bursts of invective, unfinished sentences, and harrumphs seem appropriate. So, Biden set the tone for the campaign by giving an angry State of the Union in March that no president with all his faculties would ever have composed or approved in an election year. The president’s address was dedicated to the proposition that he was a veritable 1941 version of Franklin Roosevelt, heroically fighting the modern equivalent of Hitler both abroad (in the form of Vladimir Putin) and at home (in the form of the Republican opposition). That rather frightening performance didn’t immediately lead any Democratic leaders to reconsider Biden’s abilities. Neither did a nearly incoherent debate effort. But the bullet that struck Trump in Butler, Pennsylvania killed the Biden candidacy. Donors forced the president out within days.

The election now moved onto terrain where Democrats were not prepared to fight. Reality TV had given voters—at least the ones under the age of 45—an in-built appetite for spontaneity. Though Trump is a man deficient in most of the 20th-century political virtues, when it comes to the 21st-century virtue of spontaneity he is gifted indeed. Kamala Harris made a good first impression, but there was a spontaneity gap that kept widening. Never, it seemed, could she take the slightest initiative without the approval of her communications team. The decision to shield her from press questioning for two months after her elevation was in retrospect understandable. Having risen through ethnic politics in the Bay Area, Harris had little experience making her case to people who disagreed with her. Her handlers were not going to let her learn on the fly. But the more charmed the public was by her glamour and her scripted soundbites, the more disappointed it was to find her shielded from access and view. Just as Nancy Pelosi had told Congress in 2010 that they would have to vote for Obamacare to find out what was in it, Harris’s campaign was telling the public they’d have to vote for Harris to find out who she was.

Like fundamentalist mullahs who want Western rockets without Western freedom of information, Democrats thought they could have the Trumpian tricks without the Trumpian worldview. They felt the power of his spontaneous speaking style and wanted to emulate it. Sometimes they saw it as a mere knack for inventing epithets: Lyin’ Ted, Crooked Hillary. Harris was trying to work the same kind of magic when she referred to various state-level abortion restrictions as “Trump Abortion Bans.” Sometimes they equated Trumpism with simple boorishness, as when Harris’s running mate Tim Walz called both Trump and J.D. Vance “weird,” made lewd jokes about Vance, and tried to make fun of Trump’s various late-campaign appearances working at McDonald’s and driving a garbage truck. Walz looked like he was grasping at straws. “Loser” was written all over him, the way it had been written all over an overconfident George H.W. Bush in 1992 when he entered the campaign with two weeks to go, thinking he could overtake Bill Clinton and Al Gore merely by calling them “bozos.”

Meanwhile, Trump was still an open book. He was out there giving hostages to fortune on “The Joe Rogan Experience,” making it worth a swing voter’s time to tune in—there was no telling what he might say! And for Trump himself there was zero risk. He benefitted from having been trashed by the mainstream media for nine years straight. They would disapprove no matter what he said. That liberated him to be totally honest. He gave the public a lot.

His detractors continued to accuse him of removing rationality from public discourse, and indeed Trump sometimes ranted away in reckless disregard of the truth. But, like Frauke Petry, he had made frequent efforts to make his case rationally in the course of his first term, and had seen them thrown back in his face. One needn’t belabor the examples, but the episode in 2017 when Trump was accused of describing neo-Nazis as “fine people” can stand as representative. There had been a march in Charlottesville, Virginia to protest the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. Trump, perhaps attempting to play the above-the-fray Yankee, said that it was a matter of free speech, with “very fine people on both sides.” But he was very clear: “I’m not talking about the neo-Nazis or white nationalists…. [T]hey should be condemned totally.” At which point a journalist asked, “You say they treated white nationalists unfairly?”

In this climate, rationality, if it is going to be reintroduced to politics, will need to be reintroduced on different terms. The way political media has evolved since Trump’s first term—and perhaps in response to it—gives us a sense of the unexpected ways this reintroduction might happen. Like many celebrities, Trump inhabits television as if it were his native country. For more than a half-century after its invention, television seemed to get simpler and tawdrier with every passing year. Once smartphones made it possible to carry television in a shirt pocket, people would have such short attention spans that they would lose the capacity for culture altogether. At least, that is what most observers assumed up until five years ago. But television shows got better. People abandoned propagandistic newscasts. Long-form podcasts came along, in which a guest would talk for 90 minutes—180 on Joe Rogan.

Trump seized on these new capabilities and tendencies to say the kinds of things politicians hadn’t been able to say even in 2016 or 2020. It turned out there were countervailing arguments against woke that were not available then. The powerful campaign ad showing a clip of Kamala Harris arguing for state-funded sex-change operations for prisoners—“Kamala is for They/Them; Trump is for you”—broke a taboo. Even his most loyal voters must have asked: Is he really going to go there? Is he really going to talk about the things that make me ashamed of this country? As that ad ran several times during seemingly every college and pro football game this fall, those Democrats who assumed that new media would give Trump enough rope to hang himself were shocked to see the public rallying to his side. A new political technology was bringing forth a new kind of “messaging”—it’s not even clear yet that we ought to call it oratory. What is clear is the upshot. If it is getting harder for a politician to maintain what used to be called “message discipline,” it also seems to be getting harder for his opponents to twist his words to make a trap for fools.