Books Reviewed

In 1960, at age 16, I purchased my first book. It was Hazel Barnes’s translation of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness (1943), whose 500 pages I turned uncomprehendingly. Though I could hardly afford the book, I did not regret the expense, because I had learned from Walter Kaufmann’s collection of existentialist extracts, Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre (1956), that Sartre’s philosophy was a life-changing guide to an emerging and liberating world. He had proved that radical choice would sweep away the old attachments and set the individual free. Henceforth, thanks to this learned survey of I knew not what, I would be me, the pure individual me, in a world illuminated by a single consciousness, namely mine. All our gang at school were self-declared existentialists, each committed to proving himself with an act of radical commitment: Denzil’s was to seduce a Nigerian princess who had been installed in a posh local boarding school for girls, mine was to blow up the school cadet corps’ glider with a homemade bomb. We all claimed intimate knowledge of this book that few of us had read and none of us had understood. And we all rejoiced in the message that we read into it: the message of self. As William Wordsworth wrote of another French radical movement: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive.”

By 1968, when the aftershocks of the existentialist earthquake were being felt in the streets of Paris, I was as disillusioned as the aging Wordsworth. I could not believe that anyone would take this stuff seriously, certainly not so seriously as to do what Sartre at the time was recommending, which was to pull down the fabric of French society and install a “totalizing” system in its stead. By then, however, I had read the early Sartre properly—the Sartre of La Nausée [Nausea], of the plays and novels, of Being and Nothingness, and the two studies of imagination. With a deep admiration for his gifts, I envied his ability to bring philosophy, fiction, and essay writing together, in prose that is both argumentative and full of imagined life. I wondered whether this synthesis of literary talents might be available to someone like myself, who believed the opposite of what Sartre believed, and who was convinced that life is not about self but about others. Thus did I set out on my own peculiar journey.

* * *

Sarah Bakewell, too, had an existentialist awakening, which occurred 20 years after mine, when she was swept off her feet at age 16 by La Nausée. This, if nothing else, is a proof that existentialism was not merely a fashion, but a literary experience that touches something deep in many of us, something that comes to the surface in those teenage years, when it is so clear that the world is governed by a conspiracy to exclude us, even though it is no fault of our own that we are here. Bakewell is a gifted writer and a serious thinker, whose previous book is How to Live: Or a Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010). She is able to explain engagingly the ideas of Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Martin Heidegger while relating them to the lives from which they sprang. And in this she clarifies the essential point, which is that existentialism was both a genuine philosophy, rooted in speculations that are of permanent significance, and also a way of life, in which ideas, feelings, and actions grew organically together in response to the peculiar condition of a self-destroying Europe.

The heroes of At the Existentialist Café are Sartre and de Beauvoir, for both of whom Bakewell has a soft spot. She is able to pass quickly over glaring and often inexcusable moral faults, such as de Beauvoir’s habit of grooming her female students to have sex first with her and then with Sartre, or Sartre’s excuses for the Communist genocides. Like so many commentators, Bakewell cannot find it in herself to be similarly lenient towards Heidegger, whose support for the Nazis—loathsome though it was—fell well short of the support offered by Sartre and de Beauvoir to the various revolutionary murderers who from time to time enjoyed their commitment. (Bakewell does not even mention Sartre’s public endorsement of the murder by Palestinian terrorists of the Israeli Olympic team at Munich in 1972.) I guess this is something we have to accept, now, as part of the culture—that crimes attributed to the “Right” are inexcusable, while crimes attributed to the “Left” are for the most part simply mistakes. Sartre and de Beauvoir made many such mistakes. But Sartre’s philosophy of absolute freedom and de Beauvoir’s radical feminism offered a lifeline to the adolescent Bakewell, and she clings to it still.

* * *

Bakewell brings across Heidegger’s gloomy and shut-in character, and although she repeats the now accepted platitude that he was a great philosopher—perhaps the greatest philosopher of modern times—she doesn’t hesitate to quote the oracular utterances that show him to have been no such thing. Many people whom I respect endorse the orthodox view of Heidegger, and I hesitate to say that he was a portentous old windbag who had nothing to say. The problem is that he had a way of saying nothing with a capital “N,” at a time when Nothing was on the march across our continent, and when people would prick up their ears on hearing that “Nothing noths,” or “The Meaning of Being is Time.” In emergencies we listen out for those capital letters, and forget that the mantras of the metaphysician and the slogans of the demagogue are both in the business of silencing our questions.

Bakewell gives a lively evocation of the Parisian café culture of those days. The café was a home for the metaphysically homeless, where self and other could enjoy the apricot cocktails of her title, and exchange looks across a smoke-filled room, while wondering whether any such thing is really possible. After all it is not the pour-soi (for itself) but the en-soi (in itself) that meets the eye, so how can I meet I when eye meets eye? Yet somehow it happens, and the various studies of le regard—from Emmanuel Levinas, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, and others—have changed, for me as much as for Bakewell, what philosophy can tell us about the human condition.

* * *

Bakewell expounds the arguments in a way that is, by and large, true to their inspiration, as well as imbued with her own sense of why they matter. Rare among commentators she traces the existentialist moment to the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl, and does her best to give an account of the crucial concept that he took from his teacher Franz Brentano and brought into the center of modern philosophy: the concept of intentionality. Husserl’s phenomenology begins from the recognition that the I knows itself as subject only because it targets something else: the object of attention; as Husserl put it, “all consciousness is consciousness of something.” I cannot think without thinking of something; I cannot love or fear without loving or fearing something; I cannot see, hear, or imagine without representing the world in thought. Our mental states have aboutness, presenting us with objects and coloring those objects according to the way they are given to consciousness. But the subject, the pure awareness that defines the horizon where I stand, can never be an object to itself: the subject flits from its own attention, to occupy always the position of the knower, and never of the thing that is known. Philosophy is possible, therefore, only as a study of the “transcendental self,” the observer on the edge of the world, who cannot be found within its boundaries.

“Understood in this way,” Bakewell writes, “the mind hardly is anything at all: it is its aboutness…. Nothing else can be as thoroughly about or of things as the mind is: even a book only reveals what it’s ‘about’ to someone who picks it up and peruses it, and is otherwise merely a storage device.” Husserl developed a technical language with which to isolate and explore this aboutness, believing that he could, from a study in depth of the first-person case, arrive at the essence not only of our states of mind, but also of the world as it is represented in thought. He wrote down his unending dialogue with himself in a peculiar shorthand, creating trunk-loads of notes that survived many adventures in war-torn central Europe before ending up at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, where the Husserl archive still exists, as a school within the university. (This is one of the many stories that Bakewell tells with style and sympathy, bringing Husserl to life for me for the first time.)

* * *

Sartre rightly ignored Husserl’s technical language, and the accompanying theories about the structure of consciousness. Beginning from the same premise of self-consciousness he embarked on an extended and wonderfully imaginative exploration of “what it is like” to exist as a subject, a pour-soi, conscious of a freedom that no object can exhibit, and hungry for a relatedness that can never be assured. Bakewell quotes from an essay on Husserl, published in 1939, describing what it is to be conscious, namely:

to wrest oneself from moist, gastric intimacy and fly out over there, beyond oneself, to what is not oneself. To fly over there, to the tree, and yet outside the tree, because it eludes and repels me and I can no more lose myself in it than it can dissolve itself into me: outside it, outside myself…. And, in this same process, consciousness is purified and becomes clear as a great gust of wind. There is nothing in it any more, except an impulse to flee itself, a sliding outside itself.

And so on, in emotionally laden and poetic metaphors that really do seem to tell us something about our condition, without ever giving a single reason that would carry weight with the literal-minded. Why do we have recourse to metaphor, in our attempt to say what our states of mind are like? This question—not asked, I think, by any of the existentialists, and certainly not by Husserl or Heidegger—lies at the heart of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s beautiful discussion of the first-person case in Philosophical Investigations, a work that Bakewell, alas, does not mention.

* * *

Phenomenology of Sartre’s kind lies behind all his most powerful invocations and arguments, including the incomparable description of sexual desire and its paradoxes in Being and Nothingness. But there is another input too, and one that Bakewell mentions only in passing, and in the course of describing de Beauvoir’s discussion of the alterité (otherness) of the “second sex.” The other input is G.W.F. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. This great work, which introduced the term “phenomenology” to philosophy, though not quite in its subsequent sense, was the topic of influential lectures delivered by Alexandre Kojève at the Institut des Hautes Études between 1933 and 1939. Those lectures, attended by de Beauvoir, Merleau-Ponty, Raymond Aron, Georges Bataille, Jaqcques Lacan—in short by anybody who was anybody in the French intellectual élite—implanted in all of them a common language with which to shape their response to the postwar reality. Self-consciousness and freedom are, in Kojève’s interpretation of Hegel, synonymous, and come into being not through reflection on the self but through encounter with the other, and through the “life and death struggle” that leads first to slavery, and then to the moment of mutual emancipation, when my freedom is realized through acknowledging the freedom in you. The argument, in all its many details, underlies the little that is true in Karl Marx, and the much that is true in Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and Levinas, and would have benefited from Bakewell’s candid, engaging way of presenting abstract ideas through the attempt to live by them.

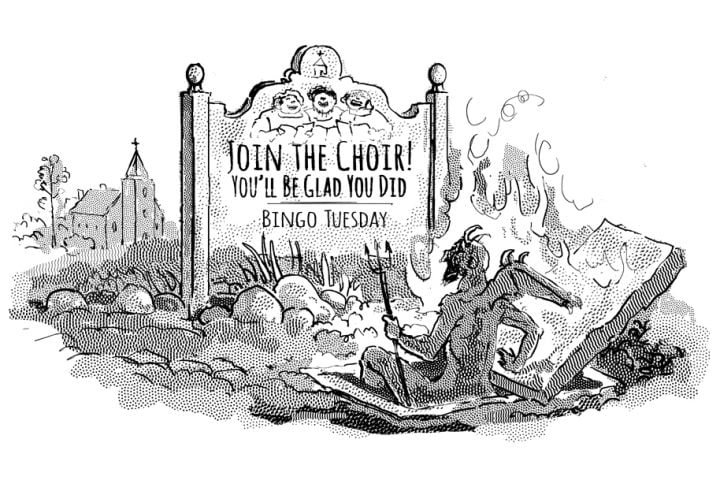

That lacuna aside, Bakewell admirably shows the legacy of phenomenology, not only in the writings of the major existentialists, but also in central European thinkers who have in their own way affected the self-understanding of our continent in modern times—notably in Jan Pato?ka and his disciple Václav Havel. Her wide and adventurous reading inspired me to follow her into some unusual corners of intellectual history, and almost persuaded me to forget the great fact that she veers constantly away from, which is that her two favorite thinkers, who were such a positive inspiration to her, were also vast negative forces in the France of their day. Their advocacy of liberation went hand in hand with a contempt for those who lived by the old middle-class values—the only values that held the French together in the postwar trauma. Their writings did much to bring about the great fissure in French society between the law-abiding “bourgeoisie” and the intellectuals who despise the bourgeois decencies. Les salauds [bastards], as Sartre called them, emerged in the century after Gustave Flaubert as the enemy, the thing to lampoon and destroy, and this enterprise, which is responsible for what is most feeble in Sartre’s writing, notably the patchwork Marxism of the Critique de la raison dialectique (Critique of Dialectical Reason, 1960), was adopted by all those who took part in the 1968 revolution, from Louis Althusser to Alain Badiou to Gilles Deleuze and Lacan, who imagined that they were so much the more glamorous for the contempt with which they greeted those who subsidized their narcissistic lifestyle.

* * *

It is in these terms that I would respond, now, to both the radical freedom of Sartre and the radical feminism of de Beauvoir. Their philosophy was, primarily, one of rejection, a refusal to emulate or be bound by the sacrifices on which social order depends. They lived in a world of self-esteem, and because they did nothing to deserve this esteem, they postulated “bonne foi” or authenticity as sufficient grounds for it. If everyone lived and thought as they did, society would come to an end, and there would never again be children. But they needed those children—how else is the stock of lovers to be renewed? Like the effete English intellectuals of the Bloomsbury Set, the existentialists depended on what Lytton Strachey called “the marrying classes” to bear the burden of society, so that they could flit from flower to flower, enjoying a freedom that could never be allowed to those whom they despised for making it possible.