Books Reviewed

A review of The Sins of the Nation and the Ritual of Apologies , by Danielle Celermajer.

, by Danielle Celermajer.

In the mid-1990s, the British government erected a statue to Air Marshal Arthur Harris on the Strand in London. "Bomber Harris," as he was known, had directed the bombing of German cities during World War II, so the memorial provoked some protest from commentators in Germany and even a mild expression of dismay from the German ambassador in London. Much of the British press expressed sharper indignation—at German complaints.

About that time, I happened to have dinner with a writer who had served as an aide to Prime Minister Thatcher in the 1980s. A serious Christian and a very reflective man, my dinner companion spent much of the evening defending his conclusion that the British—and the Americans—should feel remorse for the hundreds of thousands of civilians killed by Allied bombing of German cities. I finally said I saw the point of his arguments but did not want to give Germans the satisfaction of a public apology. "Oh, Good Heavens, no!" said my companion. "I was speaking of private remorse. A public apology would be quite out of the question."

Danielle Celermajer's book, The Sins of the Nation and the Ritual of Apologies, should have a lot to say on such questions. It does offer enough examples to pique the reader's interest in the contemporary "ritual of apologies." But it is, overall, a disappointing book. It hints at the reward for a more disciplined inquiry but is too quirky or confused to deliver that reward in its own pages.

The first full chapter of Sins describes the efforts of officials in post-war West Germany to express remorse for Nazi atrocities. Celermajer takes pains to emphasize that apologies became both more effusive and more encompassing with distance from the war. By the early 1990s, officials in other countries began to express (for the first time in explicit public statements) formal "apologies" for the role their countries had played in the wartime genocide. The United States offered its own formal apology (in the late 1980s) for detaining Japanese (and Japanese-Americans) during World War II. Various countries then voiced apologies for abuses or atrocities associated with 19th-century colonialism. Soon, as Celermajer reports, all sorts of groups seemed eager to participate in their own version of the ritual. German Christians in Cologne, for example, offered an apology for the 11th-century Crusade that started in that city. A tribe of Canadian Indians apologized for mining the uranium that fueled the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945.

Celermajer very much approves of this trend. She offers two whole chapters on Australia's efforts to express adequate apology for mistreatment of its aboriginal peoples—efforts she was evidently involved with, in her previous career as "Director of Indigenous Policy at the Australian Human Rights Commission." (She is now a Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Sydney.) But Celermajer thinks this contemporary practice challenges modern political categories bequeathed to us by "secular political theory." She explains: "rather than focusing on the individual wrongdoer," as theory would suggest, apology speaks to "the responsible community; and second, in lieu of justice through individualized punishment or compensation, it suggests the path of repentance." Rather than "reject the apology as an inappropriate mode of modern politics," she urges that we rethink "the validity of the dichotomies that divide our conceptual map into distinct and completely bounded worlds of action and meaning (e.g., religion vs. politics, ritual performance vs. administrative law, crude collectivism vs. moral individualism)" and "expand our conception of ‘the political' accordingly." So after her initial survey of public apologies around the world, she offers a chapter on the rituals of repentance as described in the Hebrew Bible and a follow—on chapter about medieval Catholic practices and early Protestant practices—and then follows with her account of the "rituals" settled upon in Australian efforts to make amends to Aborigines.

In a certain way, sins is too theoretical. Starting with German efforts to atone for Nazi horrors, by the end it is extending its analysis to cover Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld's expressions of regret over the abuses at Abu Ghraib prison. A category that can apply to the murder of millions and the humiliation of dozens is, to the say the least, a bit too abstract for the real world.

In another way, the book is not theoretical enough. Having (according to the dust jacket) "written extensively on…the political thought of Hannah Arendt," Celermajer treats Arendt as an entirely adequate guide to the whole tradition of political thought that preceded her mid-20th century musings. Celermajer never considers what John Locke or the American Founders actually said about nations and their citizens, much less what classic writers on the law of nations like Grotius or Vattel had to say on this subject. So she constantly proclaims the need to rethink our categories without examining what we used to think—when we were actually trying to think—about those categories.

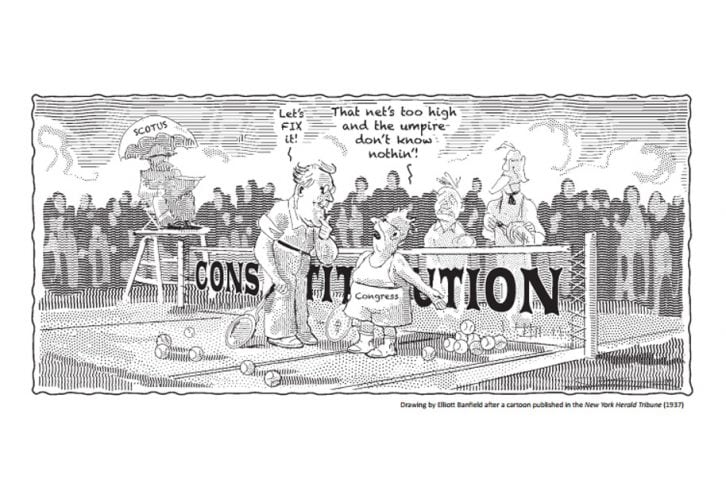

Her concern that "collective apology turns our entire political community into a mega-subject" is, at some level, easily answered: precisely the point of a state is to speak for the whole and sometimes it has to speak in apologetic terms. As John Jay noted in The Federalist, "the national government" can be more trusted with the conduct of foreign relations because it "will not be affected by…the pride" which "naturally disposes [men] to justify all their actions, and opposes their acknowledging, correcting or repairing their errors and offenses." And, as he was quick to add, "acknowledgements, explanations and compensations are more often accepted as satisfactory" when offered by a "strong, united nation."

The deeper question might be whether a liberal state, dedicated to protecting its citizens' individual rights, can properly seek to instill some sense of remorse in the citizens rather than merely expressing a sort of formalistic and impersonal—or diplomatic—acknowledgment of wrongdoing. But even a liberal political community has certain common concerns which citizens must be encouraged to share. So, like other states throughout history, modern liberal states erect monuments and have special days of commemoration to celebrate national heroes. What is that, if not a way to encourage citizens to feel gratitude and a special regard for those who have provided outstanding service to the community, such as conducting (or taking part in) great military campaigns? Like other states, modern liberal states not only punish criminals but publicize these punishments. Surely part of the purpose is to encourage other citizens to regard criminal conduct as deserving of condemnation.

Is the matter fundamentally different when one state offers an apology to another? Part of the point is to reassure others that the community acknowledges its duties and its limits in dealing with others. Why not try to assure others that feelings of regret prompting an official apology (or offer of reparation) are widely shared? After all, as Jay's paper indicates, the historic alternative to apology and reparation was war by the aggrieved party.

Locke's Second Treatise (following the account offered by Grotius decades earlier) holds that the right to punish is not even limited to victims: In the state of nature, "every man…may bring such evil on any one who hath transgressed that Law [of Nature] as may make him repent the doing of it and thereby deter him and by his example others, from doing the like mischief" (emphasis added). And this power is retained by government, acting toward outsiders, since "the whole community is one body in the State of Nature in respect of all other States or Persons out of the Community" (emphasis added).

Is it unfair to punish a whole nation for actions which not all citizens have approved? Grotius says it is just, when (as often) it is impractical to do otherwise. Locke does not even address the question. Individuals seem to have little choice but to share the fate of their community, paying for its wrongs as they benefit from its success. Those who disapprove and remain passive are, in a sense, giving tacit consent. Perhaps they did not sufficiently disapprove.

This is not simply, as Celermajer seems to think, an insight of pre-modern religious teachers. At any rate, one need not be an extreme collectivist or political cynic to see that war is, in itself, a moral instructor. Here is how Leo Strauss described the challenge of "re-education" of Germans, at a conference on that subject in the fall of 1943:

Nazi education…convinced a substantial part of the German people that large scale and efficiently prepared and perpetrated crime pays…. The reeducation of Germany will not take place in classrooms: it is taking place right now in the open air on the banks of the Dnieper [where the Red Army had launched a successful offensive to push German troops from Ukraine] and among the ruins of the German cities [due to Allied bombing]…. No proof is as convincing, aseducating, as the demonstration ad oculos: once the greatest German blockheads, impervious to any rational argument and to any feeling of mercy, will have seen with their own eyes that no brutality however cunning, no cruelty however shameless can dispense them from the necessity of relying on their victims' pity—once they have seen this, the decisive part of the re-educational process will have come to a successful conclusion [original emphasis].

So it might seem entirely reasonable for a state to offer apologies—and mean them—when it seeks to reassure neighbors (or perhaps its own citizens) that some fundamental lessons have been learned. Much of Germany's postwar pursuit of "ritual apologies" seems to have been motivated by understandable concern to reassure its neighbors, rather than satisfy victims, per se.

But Celermajer wants something more fundamental. She wants public rituals where "we redeem ourselves by treating [past victims] respectfully now (the apology) and therefore we experience and show ourselves restored to our ideal normative identity." Or, as she says later on, rituals of apology "give birth to a movement beyond the justice we already have" by "opening to the perspective of the other." I am not clear on what she means—or whether she is at all clear, herself, on what she means. But she seems to be seeking a kind of spiritual transformation, akin to those sought by sinners who (as she describes earlier in the book) offered animal sacrifices in biblical Jerusalem to atone for sins or participated in communal rituals of "reconciliation" in the early Church.

Surely it is asking too much of modern states to provide such absolution and transcendence. It was asking too much of ancient and medieval states, as was recognized at the time: religious rituals of atonement were understood as something quite different from enforcement of criminal penalties by rulers. The ultimate reconciliation sought in these rituals was reconciliation with God, the ultimate judge and ultimate redeemer of sinful humans. It is not reasonable to think that victims can provide anything like that sort of absolution.

But perhaps the victims are not really central to these rituals. Celermajer acknowledges that recent "ritual" apologies have not actually scripted a role for victims to say "we forgive you" at the end. But she does not want to fall back on praying for divine mercy: "religions' commitment to the Absolute, or a set of transcendent principles beyond the reach of actual living and changing people" would be "completely incompatible with…the democratic idea that political communities must be the source of their own norms and must be permitted to change those norms." But, she concludes, "orientation around the absolute has not fallen away entirely in the contemporary practice. Now, however, we do not call it God, but rather international law, or peremptory norms, or even the constitution."

It is hard to grasp how, after replacing God with "international law," we would promote "moral responsibility." First we invent our own standards (and never mind natural law or God's law); then we condemn ourselves (or better still, we condemn preceding generations who perhaps did not get to know our version of international law); then we can congratulate ourselves for having the moral refinement to engage in such "ritual apologies." As everyone finds some reason to embrace such rituals, we lose any sense of distinction between the regrettable, the deplorable, and the truly inhuman.

After enough such rituals, today's Germany presents itself as the natural guardian of international morality. It was the loudest Western critic of Anglo-American efforts in Iraq (even in 1991—when bombing "put innocent civilians at risk!"). The Bundestag was more emphatic than any Western parliament in protesting Israel's efforts to stop smuggling of weapons into Gaza (since enforcing a blockade with force "risks putting innocent bystanders at risk!"). The fine lines between remorse, pity, and self-pity are easily crossed, after which one reaps the congenial reward of self-approbation and self-righteousness.

I remain with my British friend: Good Heavens, no!