Books Reviewed

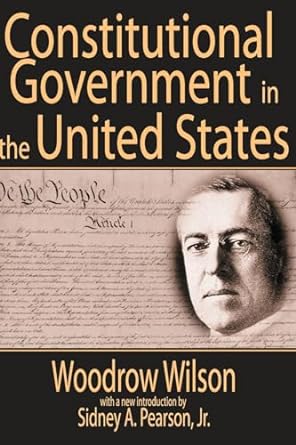

Given the importance of the Progressive movement to the direction of American politics in the 20th century, it is surprising that very little of the Progressives’ main political writings are available in print. Indeed, those of us who teach them are often forced to rely on distributing large photocopied collections of their out-of-print works. This is why the new reprint (in paperback) of Woodrow Wilson’s Constitutional Government in the United States is such a welcome development. Published by Transaction, with a new introduction by Sidney A. Pearson, Jr., Constitutional Government allows readers access to the constitutional thinking of one of Progressivism’s most important figures.

The book began life as a series of lectures at Columbia University in 1907, which Wilson was happy to deliver. He was then the president of Princeton University and in the thick of bitter campus controversy. Published in 1908, Constitutional Government would be his final book as what he called a “literary politician.” Two years later, he would be elected governor of New Jersey; two years after that, President of the United States. These lectures are the best guide to the political science he brought with him to the White House.

For Wilson, although the Constitution had been appropriate for the founding era, it needed now to be adapted to the demands of a new age. The problem was that the old constitutional order was standing in the way of progress. Its fixed, highly individualistic view of rights didn’t square with the realities of an interdependent, industrialized economy. And its checks-and-balances-ridden institutions could not accommodate the new programs and agencies needed to solve the country’s multiplying social problems. America had to shift, Wilson concluded, from a limited to a living constitution. It had to move from a “Newtonian” to a “Darwinian” understanding of politics. It had to replace government according to the Constitution with what he termed “constitutional government.”

Based upon his general objection to the founders’ understanding of government, Wilson proposed a series of “reforms” designed to undermine the separation of powers system at the heart of limited government. Among these were new theories of presidential leadership and party government, as well as a new-fangled separation of politics and administration.

Such fundamental changes in American constitutionalism are registered nicely in Pearson’s introduction to the new edition of Constitutional Government. His essay is well worth reading as a refreshing alternative to much of the standard scholarship on Wilson. Contrary to those who are taken in by Wilson’s claim that he is merely adapting the arguments of the founders to a new generation, Pearson, a political scientist at Radford University, appreciates the radical nature of Wilson’s argument. He rightly sees in Wilson “the foundation of the modern Liberal critique of the political science of the founders.” Pearson also explains how Wilson’s evolutionary interpretation of the Constitution had its roots in German idealism and historicism. In short, Pearson goes well beyond those interpreters who see the primary influence on Wilson as Walter Bagehot and other writers in the English Historical School. This edition of Constitutional Government therefore performs the dual service of returning to print a vital source of modern liberal thought in America, and providing a concise interpretation of Wilson’s role in the American tradition.