Books Reviewed

A handful of presidents faced tough challenges for renomination in the 20th century. Twice, challengers drove their presidential opponents (Harry S. Truman and Lyndon B. Johnson) from the race altogether. Three times, the race that resulted was an epic struggle that rent the president’s party and deeply affected American politics. In one, Theodore Roosevelt stormed out of retirement and took the fight to his erstwhile friend, incumbent William Howard Taft. In another, Senator Edward Kennedy, Camelot’s remaining heir, waged a long and bitter struggle against Jimmy Carter.

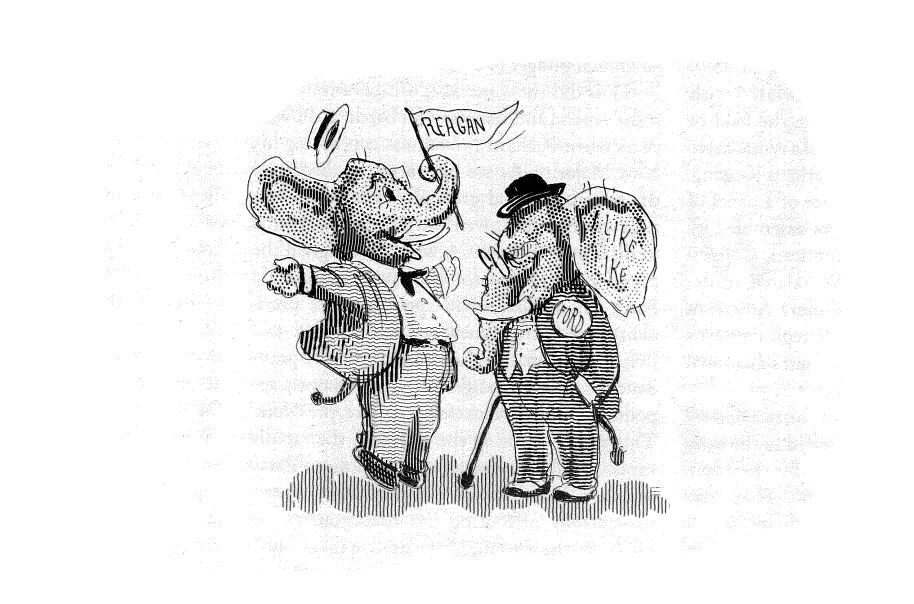

Conservative political consultant Craig Shirley examines the remaining, and perhaps the most important, case: Ronald Reagan’s 1976 challenge to (unelected) incumbent Gerald R. Ford. Shirley argues that the 1976 Reagan campaign, which is often given short shrift even by Reagan enthusiasts, laid the groundwork for 1980. In Shirley’s view, “1976 joined 1856, 1860, and 1964 as the most important Republican conventions in the party’s history, and one of the most important in American history.”

In 1976, Reagan pushed Ford to the limit. He won more caucus state delegates, and more votes in primaries than Ford. He lost the nomination by the barest of margins—1,187 delegates to 1,070—because a number of states had large blocks of uncommitted delegates under the control of pro-Ford party leaders. As Shirley argues, the nationwide Reagan organization, “Citizens for Reagan,” served as the foundation for Reagan’s activity for the next four years. His near-win against an incumbent gave him greater stature both within the party and beyond, turning him into the GOP front-runner in 1980. By appealing to conservatives in both parties (and repelling liberal Republicans), Reagan advanced the process of the parties’ ideological sorting-out. And Reagan’s impromptu but eloquent remarks at the national convention captured the party’s heart. As Reagan’s close friend, Nevada Senator Paul Laxalt argued, “Though we lost we really won.”

All in all, Shirley’s work has much to commend it. His book should be read by anyone interested in Reagan, the rise of conservatism in the Republican Party, or American politics in the mid-1970s. And although not his main focus, Shirley also offers many interesting insights into a presidential nomination process that has since faded into history.

His account is filled with meticulous detail grounded in dozens of interviews with participants in the 1976 race. He makes clear, for example, the importance for Reagan’s future of Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation in 1973. Agnew’s fall not only propelled Ford into the vice presidency and then the presidency, but removed Agnew himself as the presumptive front-runner for the 1976 GOP nomination. Similarly, Shirley examines Ford’s numerous slights to Reagan, the deal hatched between Reagan’s campaign manager John Sears and Ford’s Rogers Morton that froze Ford’s attacks on Reagan in the days leading up to the challenger’s crucial North Carolina primary win, and more generally the effect of human contingency on the course of history. (He even points out that the Watergate scandal was made possible because the uniformed policeman normally on the beat was drunk that night and unable to respond to the burglary call. In his place, three plains-clothes officers were sent in an unmarked car, and the burglars’ “spotter” was unable to send a warning.)

* * *

Reagan’s Revolution paints complex portraits of key figures in the contest. Reagan himself is shown to be mostly the same in private as he was in public, full of grace and good humor (though some around Reagan have disputed Shirley’s account of a few moments of great anger). On the Ford side, characters like Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld loom large, not unlike today. John Sears is presented as both brilliant and flawed, a spendthrift who never fully appreciated Reagan’s capacities, who made some important mistakes along the way, but who was also instrumental in persuading Reagan to run and in keeping the campaign alive at crucial moments. Richard Schweiker, the Pennsylvania Senator named by Reagan as his running mate in an unprecedented move weeks before the convention, is portrayed in a generally favorable light. While he was attacked by many conservatives as a liberal, Shirley contends: “he was from a heavily unionized state, and if his pro-union votes were removed from his record, Schweiker was fairly conservative. Schweiker was not a movement conservative. Still, he was solid on anti-Communism, solid on national defense, solid on the Second Amendment, anti-abortion, opposed to forced busing, and a leader in the Captive Nations issue.” The appraisals of Sears and Schweiker will undoubtedly strike some conservatives from that era as overly generous, but Shirley’s argument is reasoned.

Readers also meet the man who comes closest to being the villain of this story, Clarke Reed. Reed was the chairman of the Mississippi Republican Party, a Goldwater veteran who may have been more responsible than any other individual for making the GOP a viable institution in Mississippi. Having privately pledged his support to Reagan, Reed betrayed the Californian at the last minute. Mississippi’s reversal ended whatever hope Reagan may have had at the convention. Even here, Shirley treats his subject with some sympathy, though he makes no effort to exonerate or excuse Reed, who is shown as weak and pathetic rather than malicious. The sorry episode is but one historical example of many in which a great man is laid low by the egotism and petty intrigues of a much smaller man.

Reagan’s Revolution clearly demonstrates the central importance of foreign policy to the Reagan cause. It was only when Reagan turned to foreign policy—attacking détente, the Panama Canal negotiations, and the stewardship of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger—that he revived his flagging campaign in North Carolina and Texas. He capitalized on his North Carolina win by buying time for a 30 minute speech on foreign policy that was watched by 20% of American households and brought in $1.5 million dollars for the campaign.

For those interested in the processes of American presidential nominations, Shirley provides strong evidence that many of the reforms of the early 1970s were counterproductive. Those reforms were driven by a desire to make the parties more open to outsiders like Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern (and, presumably, Reagan). But Shirley explains how the campaign finance reforms of 1974 actually hurt Reagan. The Federal Election Commission, under the control of Ford appointees, took its time releasing the matching funds owed to Reagan at several key junctures. After the Supreme Court forced Congress to rewrite the legislation, Ford let the bill sit on his desk as long as possible, preventing the FEC from dispersing any funds. It should not have been difficult to predict that when government is given power over campaigns, those in government will use that power to harm their opponents. Yet somehow the lesson never seems to sink in. At the same time, Reagan may have been hurt by the post-1968 shift from caucuses to primaries. His strategists believed, probably correctly, that he could not have gotten off the ground without primaries. But in the end—like Goldwater in 1964—Reagan did better in caucus states, where money counts for less and organization counts for more.

Nevertheless, the reform process was not complete. The convention still mattered, and there were still large blocs of uncommitted delegates who could be swayed by state and local party leaders, making the 1976 presidential nominating system closer to the 1968 system than to today’s. Indeed, 1976 was the last convention that opened with no candidate claiming the allegiance of a majority of delegates.

* * *

Reagan’s Revolution has a few shortcomings. At times, for instance, it seems to contradict itself. Shirley describes Ford’s public standing as plummeting in late 1975; in another place, he gives poll results showing Ford leading Reagan and all Democrats in late 1975. Conservative congressman John Ashbrook is once described as having “stood by Reagan” in the anti-Schweiker backlash; three pages later Ashbrook describes himself as “a former supporter” of Reagan, due to the Schweiker decision. More generally, Shirley does not come down clearly on how much (or if) the Schweiker decision really hurt Reagan in the waning weeks of the contest, nor on how much (or if) his famous proposal for a $90 billion devolution of federal social programs to the states really hurt Reagan in New Hampshire. Perhaps it is impossible to render a definitive judgment on those questions, but Shirley simply offers conflicting information and leaves it to the reader to sort out.

He also occasionally indulges in questionable assertions, usually by taking a perfectly valid point and extending it too far. For example, the Republican Party is presented in 1974-75 as being in its “death throes.” Sure enough, Watergate and the 1974-75 recession had inflicted serious damage on the party, but Democrats were having plenty of problems too, despite their superficial strength in voter identification. In retrospect, the New Deal coalition broke apart in 1968 and was never really put back together. The South was unreliable, blue-collar workers were divided, and Catholics had voted for Nixon in 1972. Even the hapless Gerald Ford (as Shirley presents him) almost won against Jimmy Carter in 1976 at the nadir of Republican strength. And as Shirley himself points out, conservatives had been gaining strength in the GOP since 1964. Nevertheless, his general point is right: Without Reagan, the GOP would have been far less successful over the next quarter-century, and it would not have changed America and the world.

Still, the book overreaches when it claims: “It is unconscionable to think that any modern Republican would aggressively or gleefully embrace the growth of government or oppose the decentralization of power in Washington.” One is left to wonder where that leaves the No Child Left Behind Act and the prescription drug entitlement. Indeed, one of the open questions facing Republicans today is whether Reaganism will be the guiding philosophy of their party or a mere password, a cover for the return of domestic Nixonism.

It is impossible to know how history might have been different if Reagan had won the 1976 Republican nomination. As Shirley points out, the Reagan of 1976, though impressive, was not the fully formed Reagan of 1980. He had not yet adopted “supply-side” economics and had not fully incorporated the growing movement of social conservatives into his coalition. It may also have taken the disasters of the Carter years to finally prepare Americans to accept enough of the conservative critique to make possible a successful Reagan candidacy and presidency. But it is easier to estimate what would have happened had Reagan not run in 1976, or had run and been driven from the race after a few primaries. He would either not have run in 1980 at all (as Shirley thinks), or have started the 1980 campaign from a much weaker position. The world would be a very different place, and not for the better.