In late June, Braver Angels, a citizens’ movement seeking to mitigate partisan hatred at the grassroots, held its annual convention in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Of the 57,000 Americans who have participated in Braver Angels workshops nationwide, 750 attended the convention. On the first night, June 27, they gathered in the chapel of Carthage College to watch the televised debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. The response among both “red-leaning” and “blue-leaning” members was dismay—directed not at each other (that would have violated the spirit of the occasion) but at the grim déjà vu of having to choose between the same two faces as four years before.

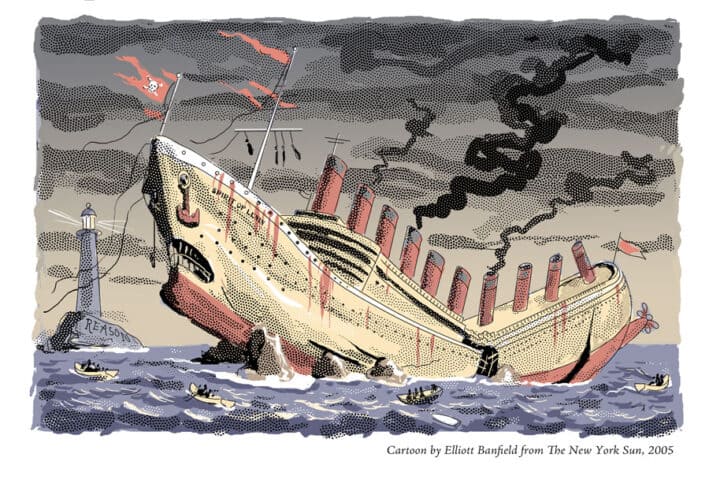

Shortly thereafter, one face got replaced, and the election, of course, proved decisive in favor of the other. To some Americans this portends a bright future; to others it augurs the end of civilization. So, partisan hatred is not likely to abate, and recent polls show a fair number of Americans think the country is on a path to civil war.

On the second night of the Braver Angels conference, there was a screening of the movie Civil War, which was still being discussed two months after its April release. As of today, the film has made $126 million at the box office. And it will doubtless make more through streaming. Not bad against a production budget of $50 million. It’s worth noting that 46% of that box office revenue was earned in 69 other countries, including Russia and China. A couple of years ago, a Chinese visitor to my university, who despite her Fulbright grant was clearly a CCP apparatchik, asked me to predict when, not whether, America would descend into civil war. She would probably see this film as the answer.

To judge by the reactions of the Braver Angels audience, they did not see it that way. Most of the people I talked to found Civil War frustratingly incoherent, not least because it offers no explanation of how and why the civil war got started. There are a few hints in the opening scene, in which a nameless president (played by Nick Offerman) declares that the “United States military” has just defeated the “illegal secessionist” states of Texas and California (known as the “Western Front”) and foiled an attempt by the “Florida Alliance” to force “the Carolinas into joining the insurrection.” Soon “the final pockets of resistance” will be eliminated, he says, and God will bless America again.

These hints suggest that the president is a latter-day Abraham Lincoln restoring the Union. Others make him out to be a proto-fascist gutting the Constitution and ordering protestors and journalists shot on sight. Equally unclear is who the hell the secessionists are. Texas and California? Florida and the Carolinas? At one point another faction, “f—in’ heartland Maoists,” is mentioned by a cynical journalist who then dismisses them as “all the same.”

Sizzle Posing as Steak

I urge the reader not to waste his or her precious time trying to figure out any of this. It is impossible to decipher whether the president turned fascist because the states seceded or whether the states seceded because the president turned fascist. This is because Alex Garland, the British filmmaker who wrote and directed Civil War, has zero interest in providing a coherent casus belli. And that goes double for A24, the New York-based production company that backed it.

Why make the film, then? The easy answer is that a lot of movies get made without anyone straining his brain about what larger meaning they might have. Because I admire some of Garland’s previous work, notably Ex Machina (2014) and Never Let Me Go (2010), I hesitate to put him in this category. But about A24, I hesitate less. Some (not all) of that company’s productions seem more heavily influenced by marketers (assisted perhaps by A.I.) than by artists with imagination. That would partly explain why, instead of a serious film about the legacy of the 1860s Civil War, or one arising from the fault lines dividing the country today, Garland and A24 have given us poll-tested sizzle posing as steak.

They also boosted the buzz. Shortly after Civil War was released, The Hollywood Reporter ran an article claiming that “[p]recisely 50 percent of ticket buyers identified as conservative and the other 50 percent as liberal.” The source for these remarkable figures was an exit poll taken on the film’s opening weekend by (surprise) A24. The writer did add that this bipartisan fandom was confirmed by anonymous “rival studio execs,” but she didn’t name any. Without doubting her integrity, I do think the article would have been more convincing if A24 had skewed the numbers slightly, and one of the editors at The Hollywood Reporter had cut the word “precisely.”

The film did find an audience, perhaps for the reason expressed by a young French woman I met at the Braver Angels screening. She was there taking pictures at the convention, and she shared with me how, as a photojournalist herself, she loved Civil War’s portrayal of the lead character, a battle-tested female photojournalist named Lee (Kirsten Dunst), mentoring a young female acolyte named Jessie (Cailee Spaeny). When I asked the French woman if she was bothered by the film’s lack of coherence, she shrugged and said she didn’t understand American politics.

This, of course, is the perspective of a great many elite-educated youth around the world. In the foreground are the concerns of identity: religion, nationality, race, and (especially) gender in all its proliferating permutations. In the background is everything else: history, politics, science, society, the arts—all those things that matter to old people but cannot be analyzed correctly except through the lens of identity.

Much as I reject this worldview, it helps explain Civil War. The entertainment industry has long been preoccupied with demographics, but identity politics turned that preoccupation into an obsession. Which made it more challenging than ever to appeal to a general audience. But with the shift toward streaming, that no longer seemed to matter, because theaters were dying anyway. Today, however, they are coming back to life and there is a growing market for films with broad appeal to show in them. This sounds like good news, but only if the industry can revive the forgotten art of pleasing most of the people most of the time.

I call this an art because it cannot be done by data. Civil War is a perfect example. The data’s prime directive is to appeal to youth, so the ambitious dreamer Jessie must be placed at the center of the story. The theatrical market skews toward young men, so there must be plenty of action, from ugly incidents in the hinterland to a massive World War II-style battle at the end. It is also imperative to attract women, so the tough, 40-ish woman Lee must be placed at the center as well. (Dunst takes full advantage of this; her performance almost makes the film worth watching.) Above all, fitting these disparate pieces together in a halfway plausible narrative requires keeping the civil war itself at such a remote and blurry distance that the audience will quit trying to understand it.

The Only Problem Is the People

The result is a film that begins with the aforementioned presidential speech, then shifts to a New York hotel room, where Lee is glumly watching him on TV. She takes a photo of his face on the screen, then looks out the window at a fiery explosion illuminating the skyline. The next morning, she and her colleague Joel (Wagner Moura) speed in a white van marked PRESS to a city neighborhood where panicked residents are demanding clean water. When the police respond by beating them, people start taking photos and videos. But for reasons not explained, this is a world without cellular service or internet. So, these are not “citizen journalists” using smartphones, they are professional photojournalists wielding Canons, Panasonics, Sony Alphas, and Nikons.

Chief among them is Lee, her face impassive as a death mask. Both she and Joel, a reporter addicted to adrenalin, are war correspondents conditioned by long experience to observe mayhem without stopping to intervene. But when a young woman is struck by a police baton, the plot requires Lee to rush uncharacteristically to her side. The young woman is Jessie, of course, and amid the chaos she touchingly calls Lee “my hero,” and Lee reciprocates by giving her a press vest. Moments later a suicide bomb explodes, and in the sinister silence that follows, Lee reverts to type, methodically seeking the best angle from which to photograph the freshly killed bodies on the pavement. Jessie is in a state of shock, but predictably she summons the moxie to raise her Leica and snap her hero snapping the dead.

The critics have compared Civil War to a group of 1980s films—The Year of Living Dangerously, Under Fire, The Killing Fields, Salvador—that follow the adventures of good-looking macho journalists dodging bullets in faraway places like Indonesia, Nicaragua, Cambodia, and El Salvador. True to that genre, the horrific scene of the suicide bombing is followed by a hilarious scene of reporters getting drunk in the bar of their hotel. But sitting apart are Lee, Joel, and Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson), a veteran reporter for “what’s left of the New York Times.” The president is lying through his teeth, Sammy says, because contrary to his claim of victory over the secessionists, the secessionists are in fact on the verge of seizing Washington. Time is short, so, determined to get the scoop on the president’s capture and likely execution, Lee, Joel, and Sammy set off the next morning for Washington, accompanied by Jessie.

To avoid the interstates, which have “vaporized,” and Philadelphia, which “you can’t get anywhere near,” our intrepid journalists head west toward Pittsburgh, then circle back through West Virginia toward D.C. This journey—which was filmed in DeKalb and Clayton Counties outside Atlanta, Georgia—takes up a big chunk of the film, which is odd, because most of the landscape appears untouched by the war. Indeed, the white van marked PRESS rolls through mile after mile of a calm and verdant swath of rural America. The only problem, it seems, is the people. At no point in their journey do our foursome meet the sort of decent, hardworking, family-loving folks whose praises are sung by politicians past and present. Instead, they find themselves in a sunshiny hell where everyone is pale, male, armed to the teeth, and not too bright or even right in the head.

Their first stop is a rundown service station in the middle of nowhere (meaning western Pennsylvania), where Lee, the toughest of the lot, negotiates the price of gas with a trio of white locals cradling assault rifles, and Jessie ventures off in search of something she glimpsed from the road. One of the locals, a young dude sporting a backwards baseball cap, follows her. Lee brings up the rear as they approach two men, blood-drenched but still alive, hanging by their wrists in a half-demolished shed. Grinning, the young dude tells Jessie that the men are looters and that he and his buddies can’t decide whether to torture them some more or just finish them off. He asks Jessie to make the call, but she is frozen in horror. At that point Lee neutralizes the situation by asking the dude to pose with his victims so she can take his picture. Photojournalism to the rescue!

The foursome then drive through a devastated suburban shopping area and spend the night in an empty parking lot watching tracer projectiles fire in the distance. The next day they embed themselves in a brutal skirmish between casually dressed irregulars and uniformed soldiers that ends with the summary execution of four soldiers, followed by a gleeful strafing of their bodies by a long-haired gonzo in a plaid shirt. Which army the soldiers belong to, and who the irregulars are, is of no apparent interest to either Lee or Jessie. The reason for this, obvious but never articulated, is that they are seeking the Pulitzer for photos, not stories. As for the reporters, Sammy is too old to do anything but watch, and Joel is mainly in it for the “rush.” No one is writing or filing any reports, so why should we care?

The next day the foursome enter an inexplicably peaceful town and linger until they spot snipers on the roofs, poised to shoot anyone who is not peaceful. A few miles down the road they come upon a deserted golf course decked out with Christmas decorations and a loudspeaker playing “Jingle Bells,” where a dead body lies in the drive and a duo of heavily camouflaged men are exchanging fire with a sniper holed up in the clubhouse. To Joel’s questions, “Are you WF [Western Front]? Who’s giving you orders?”, one sighs, “No one’s giving us orders, man. Someone’s trying to kill us. We’re trying to kill them.”

After retreating from this mindless shootout, our foursome regain their animal spirits when a pair of fellow journalists in another car pulls alongside, and a rollicking high-speed reunion ensues. But things go from bad to worse when the other car makes a wrong turn and ends up in the clutches of a deranged local (Jesse Plemons), busy filling a mass grave with people who do not measure up to his standard of “100 percent” Americanness. In case we miss the point, this genocidal maniac is wearing bright red sunglasses. The fellow journalists, one Latino and the other Chinese from Hong Kong, do not survive this encounter. But thanks to Sammy (who happens to be African American), Lee, Joel, and Jessie do.

It’s So Much Fun to Blow Up Washington

Throughout this nightmare journey, the only respite is an overnight stay in a dilapidated sports stadium turned into an NGO-sponsored camp for refugees—all of whom are either people of color or visibly countercultural. So, when our foursome arrive in Washington, they (and we) are energized by the sight of two great armies massing to pulverize the nation’s capital. Now, at last, this looks like a war!

Garland and his crew clearly relished the planning and execution of the battle sequence, which is quite impressive, although at 15 minutes it is a whole lot shorter than, say, the Siege of Stalingrad. The live action was filmed in a replica of the buildings and streets surrounding the White House, painstakingly constructed in a parking lot in the tiny town of Stone Mountain, Georgia. In a long interview with a website called The Ringer, Garland’s production team waxed eloquent about the “aural nightmare” of the soundtrack, the live portions of which were so deafening that the local TV station ran a story about residents being kept awake for several nights running.

I could not help noticing the contrast between the production crew’s delight in the ear-bleeding noise they were making, and their reported rebuff of the residents’ complaints. According to the local TV station, the neighbors received notices that the “simulated gunfire” would continue between 7:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m. every weeknight from May 11 to May 20, and after registering their objections, the only reply they got was a notice extending the torment through June 7.

There is a civil war going on in America, but it looks nothing like the meaningless, big-budget battle that was so much fun to make. Instead, it looks like the recent election, which exposed a deepening fault line between Americans who live in cities and those who live out…where? Some say in rural America, but others say in the sticks, the boonies, flyover country, the middle of nowhere. This fault line is not racial. Stone Mountain, the town whose complaints were blown off by the film production crew, is majority black. And though the white population of rural America has its share of crazies, the film’s exclusive focus on gun-happy sadists and amateur Nazis is the worst kind of elite condescension. This civil war, the real one, is as mundane and insidious as the blind eyes and deaf ears that Americans now routinely turn toward each other. On the day when somebody releases a true-to-life movie about that, I will buy the first ticket.