Books Reviewed

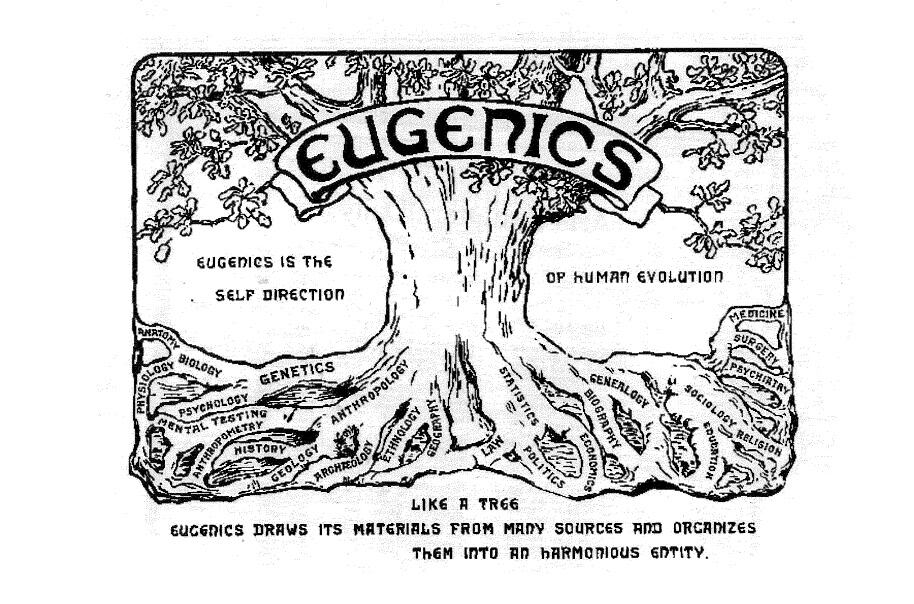

For early 20th-century American elites in the full flush of the Progressive movement, regulating reproduction through eugenics offered a promising solution to the multiplying social problems of the modern age. That man was an evolutionary being they had no doubt. But he had now progressed to the point where he could take charge of his own evolution, both political and biological, and replace the wasteful methods of natural selection with the efficient and ethical method of science. For the sake of the race’s improvement, particularly the part of it in their own country, the eugenicists advocated a broad, high-minded program that included state-sponsored sterilization, immigration restriction, birth control, and restrictive marriage laws.

All this is in the history books, of course, even if carefully kept from full view. What Christine Rosen, a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, brings to the table in her well-researched and engaging study, Preaching Eugenics, is the eager participation of many religiously-minded Americans in the eugenics project. “During the first few decades of the twentieth century,” she writes,

Eugenics flourished in the liberal Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish mainstream; clerics, rabbis, and lay leaders wrote books and articles about eugenics, joined eugenics organizations, and lobbied for eugenics legislation. They grafted elements of the eugenics message onto their own efforts to pursue religious-based charity in their churches and adopted eugenic solutions to the social problems that beset their communities. They explored the eugenic implications of the biblical Ten Commandments and investigated the hereditary lessons embedded in the parables of Jesus.

Rosen presents ample evidence of cooperation between religious and secular eugenicists. In 1926, the American Eugenics Society conducted the first “eugenic sermon contest.” The minister, priest, or rabbi who best addressed the topic “Religion and Eugenics: Does the church have any responsibility for improving the human stock?” brought home $500. During the 1920s, Eugenics magazine published a special “preachers issue.” Rev. Kenneth C. MacArthur contributed an article that linked eugenics with the Kingdom of God. Eugenics, MacArthur reasoned, would improve “the very material from which to recruit the citizenry of the commonwealth of Christ among men.” “The more fully [eugenic proposals] are adopted,” he concluded, “the more rapidly will the ends for which the church exists be furthered.” MacArthur subsequently landed a monthly column in the magazine.

Clergymen regularly enrolled their households in “Fitter Family” contests sponsored across the country by the American Eugenics Society to promote “a feeling of family and racial consciousness and responsibility.” Rev. Henry Apel’s family earned top prize at a Kansas state fair, where the winning clan earned a customary victory lap in an automobile decorated with a banner celebrating “Kansas’ Best Crop.” And clergymen eagerly filled positions in eugenics organizations. Rev. Newell Dwight Hillis advised the Eugenics Record Office—the movement’s de facto headquarters, located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York—and organized the Race Betterment Conference of 1914. Within the American Eugenics Society, the Committee of Cooperation with Clergymen was one of the largest and best-funded branches.

Rather than avoiding religion, eugenics organizations sought to add theological force to their arguments. To provide the “eugenic faith” with an “accessible credo,” the American Eugenics Society published a Eugenics Catechism. (“Q: What is the most precious thing in the world? A: The human germplasm.”) Not to be outdone, Albert Edward Wiggam, a nationally known eugenicist, handed down “Wiggam’s Ten Commandments.”

* * *

Before Preaching Eugenics, the conventional view had reduced the relationship between scientific and religious opinion in early 20th-century America to a single battle over evolution at the famous Scopes Monkey Trial (1925). On all hot-button issues, religion and science were supposedly at loggerheads. Rosen tears apart this mistaken assumption. The Scopes Trial notwithstanding, her book shows that religious and secular opinion shared much in common when it came to the era’s broader attempt to spur human evolution through eugenics.

Rosen offers several reasons for this long overlooked nexus between religious and secular eugenicists. As Rosen explains, both science and religion pay close attention to what lies inside human beings, and this fact had important consequences at the turn of the 20th century. Hereditary studies were then a new phenomenon, capturing much public attention: a famous account of the Jukes family detailed seven generations of degenerate behavior. These hereditary studies led to the conclusion that anti-social conduct was passed on genetically. To some religious thinkers, this merely affirmed Scripture’s repeated guarantees that a tree may be judged by its fruit. Rosen notes that Rev. Oscar McCulloch published one of the first eugenic family studies. Dismayed by what he saw as the “decaying stock” around him, the Indianapolis minister drafted and successfully lobbied for legislation that authorized state boards to “take charge of children of vicious or incompetent parents.” Indiana, McCulloch’s home state, would later become the first state to legalize eugenic sterilization.

In addition, the theology of the Social Gospel movement pervaded mainstream Protestant congregations, which helps to explain the eugenics movement’s popularity and cachet. Keen supporters of reform, Social Gospel adherents saw redemption as a matter for society as much as for the individual. By reforming Mammon, they believed that man could usher in the Kingdom of God on earth. Thus Social Gospel leaders took active roles in efforts to address the factors deemed responsible for social decay. They organized charities that sought to alleviate poverty and to improve public health, housing, and nutrition standards. Within the Social Gospel movement, however, some believed that targeting the environmental factors responsible for social decay was insufficient. Persuaded by the eugenic family studies he had conducted, Rev. McCulloch argued that charitable assistance encouraged recipients “in this idle, wandering life, and in the propagation of similarly disposed children.” Stronger measures were necessary.

Initially, eugenicists—both secular and religious—had adhered to a philosophy of “positive” eugenics, most famously articulated by Theodore Roosevelt, which emphasized increasing the reproduction rates of society’s good stock. By the early 20th century, “negative” eugenics, with its emphasis on limiting the population of those deemed less fit, gained the upper hand within the movement. This change coincided with the rise of an administrative elite, or what historian Christopher Lasch referred to as “helping professionals.” With scientific precision, these managerial experts could improve the commonweal by regulating the selfish impulses of defective individuals. Emboldened by advances in medical technology, negative eugenicists openly supported state-sponsored sterilization.

As Rosen shows, many religious leaders went along with the trend toward negative eugenics. At the 1927 Episcopal Church Congress, Rev. Henry Lewis defended the “sterilization of mental defectives.” Rt. Rev. Ernest W. Barnes explained that any objections to “repressive action” will vanish “[w]hen religious people realize that, in thus preventing the survival of the socially unfit, they are working in accordance with the plan by which God has brought humanity so far along the road.” Rev. George Reid Andrews, who left active ministry to serve as an official in the American Eugenics Society, proposed in one 1937 speech that the best way to prevent social malaise was to “get these people out of circulation,” referring to “idiots, imbeciles, and morons.”

Physicians, reformers, state lawmakers, and finally the U.S. Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell (1927) registered their support for eugenic sterilization. In the years immediately following Buck, 18 states introduced legislation authorizing eugenic sterilization, and in the next decade the number of men and women sterilized in state institutions quadrupled. On top of its moral repugnance, the Buck decision illustrates the hubris behind state-sponsored sterilization: that government experts could know which members of society were unfit to have children. Though Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.’s, quip in the majority opinion is notorious (“Three generations of imbeciles are enough”), few know that Vivian Bell, the supposedly feebleminded daughter of Carrie Buck, did well enough in her brief time at school to land on the honor roll.

Preaching Eugenics includes a chapter on the Catholic Church’s opposition to sterilization. American Catholic officials such as Msgr. John A. Ryan vociferously opposed eugenic sterilization, and Rome officially condemned the practice in the 1930 encyclical Casti Connubii. Interestingly, the Church’s position against sterilization relied upon more secular reasoning than did the practice’s many religious supporters. In Casti Connubii, Pope Pius XI drew on natural-rights philosophy to link the right of bodily integrity with the limits of state power: “Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects, therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason.”

Preaching Eugenics comes at a time when “religious” and “conservative” are taken as one and the same. Yet, as Rosen ably shows, one of the major Progressive-era efforts benefited from plenty of religious zeal. Preaching Eugenics is not simply revealing history, but an insightful commentary on contemporary debates, where it is not always clear which end of the political spectrum is the more dogmatic: the “secular” side that believes only fully conscious individuals deserve complete legal status, or the “religious” side that believes that a human body is enough to warrant human dignity.