Books Reviewed

Americans have embraced many religions over the years, but religious liberty was part of almost all of them —and so too (naturally enough) was devotion to the First Amendment’s guarantees thereof. This enduring consensus could be illustrated by countless testimonials of mainstream political and religious figures, from John Adams and John Witherspoon to Bill Clinton and Billy Graham. A more cogent demonstration, however, might be to canvas the attitudes of America’s religious outsiders.

Catholics, for example, long suffered Protestants’ suspicions of dual loyalty. Even so, one would search in vain among the Church’s bishops for a prelate who had any doubts about the First Amendment. New York’s antebellum (and Irish-born) Archbishop John Hughes was a muscular opponent of Protestants’ claims to possess the religious key to being truly American. But Hughes never wavered in his devotion to America’s religious freedom. He relished his public debates with leading Protestants about how Catholicism was a better fit with our institutions of religious liberty than, say, Presbyterianism.

Or consider Mormons, harassed during the second quarter of the 19th century wherever they settled. Yet Latter Day Saints founder Joseph Smith ran for president in 1844 as a champion of the Constitution. Mormons now embrace patriotism and law-abidingness as nearly sacred duties, and among religious groups may be unsurpassed in their devotion to the Constitution.

Notwithstanding their disparate ethnic identities and varied appropriations of Judaism, America’s Jews have always embraced the First Amendment. Whereas in 1916 President Woodrow Wilson’s nomination of the non-observant Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court touched off a spasm of anti-Semitism and a bruising four-month confirmation battle, by 1946 American Jews were a dominant force in the Court’s substantial renovation of Religion Clause doctrine along secularized lines.

Examples of such “outsider” embraces could be multiplied. Indeed, when it comes to religious liberty, almost everyone has been an “insider.” Religious liberty was a strategic linchpin of the whole experiment in free government. Americans believed that their experiment in liberty depended in some essential way on the people’s virtue, especially on piety and the foundation given to morality by religion. But in a free society government could do little directly to inculcate those virtues. Thus, Americans’ security and prosperity depended heavily on the effects of religion and the exertions of religious institutions. The resulting joint ventures included government-assisted religious schools, hospitals, and charities—all the mediating structures that populate civil society.

* * *

Religious freedom, then, was central to American political discourse and law for more than two centuries. It attracted Pilgrims and the world’s “teeming masses” to our shores, then cemented their allegiance once they arrived. From the moment they stepped off Ellis Island, immigrants could feel America’s gravitational pull through its promise of religious liberty. Though often imperfectly realized, religious liberty was a centripetal, defining force in the American polity, a salve especially for those whose rights were not fully secured.

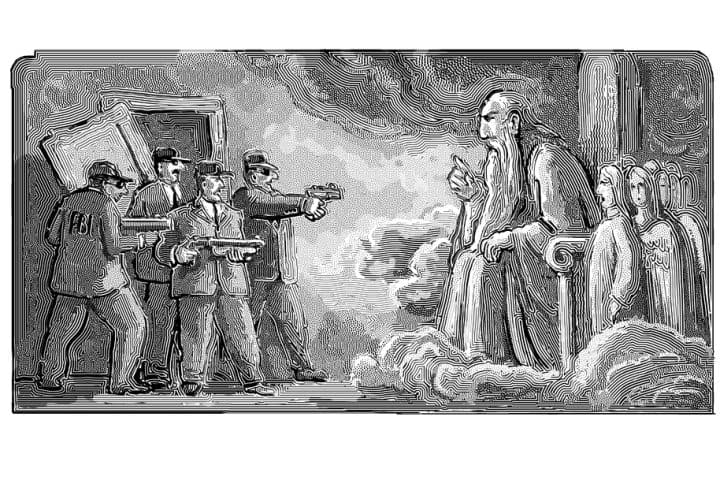

Now? Not so much. Religious liberty is scare-quoted in mainstream media as rhetorical cover for bigotry and hate. Huge swaths of the business community have soured on it. Academics deconstruct it, and our politicians are mostly afraid to talk about it. Just 23 years ago a unanimous House and nearly unanimous Senate passed, and President Clinton signed, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. After it was the basis of the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision in 2014, however, the American Civil Liberties Union was one of many voices demanding the law be narrowed or even repealed.

* * *

This upending is the subject of Mary Eberstadt’s It’s Dangerous to Believe. Her previous books Adam and Eve after the Pill (2012) and How the West Really Lost God (2013)—on the sexual revolution and secularism, respectively—showed Eberstadt to be one of America’s most discerning cultural critics. It’s Dangerous to Believe solidifies that ranking by showing that “the future of religious freedom…appears more clouded than at any time since the American founding.” The book is chiefly a chronicle of recent attacks upon the religious liberty of “traditionalist” believers, especially Christians. Eberstadt notes that just a “few years into the third millennium, in a transformation that has taken almost everyone by surprise, these believers have gone from being mainstays of Western culture to existential question marks within it.”

Some of the events Eberstadt relates will be familiar. The Obama Administration’s “contraception” mandate, for example—at issue in Hobby Lobby—required the vowed-to-chastity Little Sisters of the Poor to provide themselves and their employees with free birth control pills. Also featured is the Supreme Court’s 2015 same-sex marriage decision, Obergefell v. Hodges. Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion included a glib paragraph telling those worried about its implications for religious liberty…not to. The four dissenting opinions each rebuked this empty assurance. According to Justice Samuel Alito, those who “cling to old beliefs will be able to whisper their thoughts in the recesses of their own homes, but if they repeat those views in public, they will risk being labeled as bigots and treated as such by governments, employers, and schools.”

It’s Dangerous to Believe is much more, however, than a chronicle of intolerance. Eberstadt’s narrative provides shrewd analysis by offering historical perspective, from the Salem witch trials through and beyond McCarthyism. She drills beneath the surface turmoil to diagnose, prescribe, and even prophesy a bit. Her central questions are: “How can we get out of this punitive place?” and “Where will we go?”

One reply to the latter question Eberstadt mentions is the “Benedict Option.” Named for the founder of the Benedictine monastic order and popularized by journalist Rod Dreher, it counsels the faithful remnant to withdraw from the corrosive larger world, the better to preserve an integral Christian life through our new dark ages. (The Amish and Hasidim come to mind as parallels.)

Eberstadt sets this option aside. Eberstadt’s “we” is not that of the Benedictines, who wonder how to keep their way of life intact after concluding that the world is going to hell and there is really nothing they can do about it. Eberstadt retains hope; she means to resuscitate our country. The “we” of her book is neither traditionalists suffering under foot nor those stepping on them. It is all of us. The point is to call America home. It’s Dangerous to Believe is basically an open letter to the American people.

* * *

She writes that our “time of moral panic” is unprecedented, “driven by secularist rather than religious irrationalism.” We are in the grip of a fever induced by an overdose of gender theory and the elevation of sexual satisfaction to a moral right and duty. Panics, like fevers, are transitory and have cycles. Thus, we cannot indefinitely deny the reality of our embodied selves by entertaining dozens of gender options, or by subordinating the interests of every kid in a grade school to whether one “transgendered” eleven-year-old reports feeling uncomfortable in the restroom. And so we will not. Something closer to moral sanity will ultimately return to our society.

Secondly, Eberstadt writes, “The path to a more magnanimous place begins” with recognizing that we are living through “a contest of competing creeds, and competing first principles.” The new religion, “secularist irrationalism,” is not centered upon God. It is a “quasi-religious faith in the developing secularist catechism about the sexual revolution.” At the root of this faith is raw subjectivity, empowerment, experience, emotion—in short, irrationalism.

* * *

These “secular progressives,” Eberstadt’s term for the new sect, are oddly related to their apparent forebears, such as John Rawls in the academy and Justice William Brennan on the Supreme Court. These conventional liberals effectively protected sexual deviance by and through claims about the limits of the state’s coercive power, and the scope of tolerance and privacy in a pluralist society. Their approach to political life presumed a more or less traditional understanding of religion: that religions characteristically present an encompassing worldview, replete with what Rawls called “comprehensive doctrines” about the good. Central to these doctrines was an objective morality, which included moral norms held by believers to be true regarding sexual activity.

Conventional liberals’ resulting strategy was to craft structures and defend principles that bracketed religion in political matters, thus blunting its alleged tendencies to impose an overarching account of the cosmos on everyone. They tried to privatize religion, speaking habitually of government neutrality about moral norms. The late Richard John Neuhaus demonstrated the dangerous implications of this project in The Naked Public Square (1984).

It is vitally important to recognize the truth of Eberstadt’s assertion that today’s postmodern progressives do not seek to limit the mischief of religion with fences and improvised political axioms. Theirs is not principally a political doctrine at all. Instead, they profess an encompassing view of sexual experience and identity, a “religion” they hold to be true. Its precepts include: a metaphysics about our bodies and our identity; an account of human flourishing to which regular sexual satisfaction is essential; and a set of moral norms about the subjectivity of sexual morality. They seek to make their version of the truth the operative principle of our law. To them, traditional sex ethics are not only false but they stunt and dehumanize their adherents. Traditionalism may have to be tolerated, but we are still saddled with yesterday’s vocabulary and rhetoric of neutrality, when in truth what Princeton’s Robert George calls a “clash of orthodoxies” rages about us.

Eberstadt’s key insight is that the lion shall have to lie down with the lamb. To traditionalists, she says:

[N]either the accused witches of Salem nor the objects of the Red Scare were able to end those moral panics on their own. Momentum for change had to come from the other side. The same is true of the present antagonism toward religious citizens.

Marginalized believers, in other words, need allies.

Eberstadt calls on progressives to acknowledge “that things have gone too far.” They must find “a way to coexist with affronts to [their] own orthodoxy, not suppress them.” The practical reason for doing so is that progressivism “faces insurmountable obstacles to its desire to impose its orthodoxy on everyone else.” Not only is there “too much heterodoxy afoot,” too many dissenters, but the casualties of the sexual revolution are too numerous. And, in case the number of lives broken by our sexual libertinism is not sufficiently compelling evidence, then perhaps their maldistribution might suffice. It’s Dangerous to Believe points to the inequality produced by this revolution, like so many before it. Extending the argument she made in Adam and Eve after the Pill, Eberstadt writes, “[T]he poor are the canaries in the coal mines of the sexual revolution.”

* * *

If the reigning order is unsustainable and indefensible, what exactly will the new normal be? Time is of the essence: the fever could last long enough to turn an entire generation of Americans against religious liberty. Quite possibly, a generation raised to disdain religious liberty will not know how to reconstitute it.

Furthermore, any once-and-for-all judgment about our prospects must attend to another social revolution. It has roots in 19th-century religious liberalism, Transcendentalism, and Romantic thought, all of which converged to make religion a matter of the heart. Secularist progressive orthodoxy is jealous of false gods. The subjectivism that deconstructed our understanding of sex has colonized our understanding of religion, too. And as religion goes, so goes religious liberty.

In our age, the foundation of value when it comes to religion is the same as that for any other aspect of personal identity. Neither a religion’s affirmation of realities seen and unseen, nor its truths about obligations to a greater-than-human source of meaning and value are important. Rather, the measure of worth is “authenticity,” which in turn is one’s own interpretation and narrative about one’s experience, emotions, viewpoint, and desires.

Vocabularies of self-definition and self-fulfillment stalk today’s believers. For many, religion is morphing into a gauzy spirituality, an aspect of the project encompassing individual self-invention and -presentation. That conception of religion already prevails in our law, in the academy, and in much of popular religion on the airwaves. It has found its way into our churches, even the more traditional ones. The cultural critic Philip Rieff wrote in 2005 that “the orthodox are in the miserable situation of being orthodox for therapeutic reasons.”

If this religion—subjective, non-rational, an aspect of individual identity—is what we have, then maybe we also have the religious liberty we deserve.