For much of the 20th century The Man with the Golden Helmet was esteemed one of Rembrandt’s greatest paintings. The brilliant play of light on the gilded helmet, the subject’s shadowed face and pensive, down-turned eyes, and the secondary glint off the metal of the gorget seemed to most viewers a bravura display of the master’s technique. But by the 1960s some scholars had begun to question whether Rembrandt had in fact painted it; and two decades later, after extensive analysis, a scholarly consensus arose that it had probably been done by one of Rembrandt’s students.

What are we to make of this? Is the painting still a masterpiece? Did we set too high a value on it when we mistakenly thought it a Rembrandt? It is still the same picture: do we get less pleasure from it now that we strongly suspect it to be by a lesser hand? Why did we love it in the first place: because it was a brilliant artistic achievement, or because (as we thought at the time) it was by Rembrandt? These questions have no simple answers. They are all related to the intractable problem of taste.

Judgments and Standards

Taste is the faculty by which we make judgments about art. The term of course has broader social uses: a gift, a comment, any form of public display may, depending on the circumstances, be thought in either good or bad taste. Yet even in our social interactions, things are rarely straightforward. Who is to say that an act is in bad taste? One person might ignore certain social conventions, thinking them out-of-date, while another, more finicky sort might judge that behavior a violation of good manners.

Such conflicts are inevitable: the very notion of taste contains within itself two ideas in constant tension. First, taste is always personal: a judgment, but one’s own judgment. The idea derives from our physical sense of taste. It takes no great powers of observation to notice that different people prefer different foods. I like cilantro, you do not. As the Latin tag has it, de gustibus non est disputandum—there is no disputing about tastes.

And yet, however much we have a right to our own likes and dislikes, such judgments are often measured against a standard. For instance, the man who refuses to eat spinach or asparagus is unlikely to be considered a discerning judge of fine food. These two principles—the autonomy of the individual taste and the existence of some broader principle of excellence—are perpetually at odds. Each of us navigates between them, sometimes vindicating our own preferences, other times yielding to (and perhaps learning from) the taste of others.

Taste in the arts adds another level of complexity. Even when we are talking of the physical senses, we recognize that all people are not the same. Most of us know someone with a more delicate palate or a more sensitive nose than we have. Your eye doctor can even test your ability to see the full spectrum of colors. We find similar variety in people’s sensitivity to art. Some are more attuned to the play of words, others to the visual arts, still others to music. And within each category, the difference in responsiveness is enormous.

Alan Bennett makes this point in his play A Question of Attribution; his speaker is Anthony Blunt, the art critic and Cambridge spy: “Kenneth Clark was saying the other day…that people who look at old masters fall into three groups: those who see what it is without being told; those who see it when you tell them; and those who can’t see it whatever you do.” This remark, cold and hard as it is, seems largely correct. Ask anyone who has taught literature or art history at the college level: the professor will recognize these three groups—the sensitive, the teachable, and the dull. It is not necessarily a matter of intellect. I once heard a brilliant economist talk about a novel: he noticed everything in it but the art. It is a matter of taste.

Before I go any further, let me add a few caveats. I intend to draw most examples from the visual arts. My arguments will apply just as well to literature and music, but the terrain is too vast to stick one’s nose into every hollow or fissure and hunt about for illustrative specimens. On top of that, having spent my academic career teaching literature, I hope to escape the dead hand of professionalism by working in the spirit of the amateur. Finally, I want to avoid—at least until the end—any contentious disputes between high and low taste, between Mozart and Mötley Crüe. For the purposes of this essay, there is such a thing as great art.

Back to Alan Bennet, and one qualification about Kenneth Clark’s typology. Those who see what is going on in an Old Master painting “without being told” can do so only because they already know something about the form. Art is never transparent. There are no wholly intuitive responses to it, not even to the Old Masters. We assume, perhaps rightly, that anyone can enjoy the beauty of a sunset or the scent of peonies: the pleasures of nature must certainly be available to all. But the response to art is different. Art is not a part of the natural world; it is a human contrivance, and to appreciate it we must undergo some form of acculturation. Before Western music conquered the world, the shamisen (a three-stringed traditional instrument) would have sounded as natural to Japanese ears as the guitar does to our own. But nature had nothing to do with it: we hear a culture’s vibrations in the strings of each instrument. No one, in fact, is born a connoisseur of Old Master paintings, just as no one is born a reader of Alexander Pope or a devotee of Mozart. Our responses to art involve both nature and nurture, an inherent sensitivity shaped by experience. Taste must always be trained.

Current Trends

The idea of training one’s taste may seem alien, even repugnant. Perhaps beauty should be recognizable in any circumstances. But one’s own experience will generally tell against this claim. Consider the Byzantine icon. Those of us who have trained our taste on the Western tradition of religious art from Giotto to Guido Reni are likely, upon first encountering an icon, to find it static, distant, artistically unsatisfying. In trying to make sense of it, we might see it as a “precursor” of Cimabue or Duccio. But how can that be relevant? The work was never intended to aim toward something grander. Created in a tradition, it had had its own purposes and expressed a particular artistic idiom. Such works seem alien to those never exposed to that tradition. Whatever made them precious eludes us.

And yet, strange or unfamiliar art will sometimes break through our prejudices, upsetting our expectations and becoming a part of our own personal aesthetic. Japanese prints, for instance, had a marked influence on 19th-century European art, as did African masks in the early 20th century. An openness to such experience may in fact be a sign of a particularly responsive taste. We may still know nothing of the work’s original social and cultural meaning, but that does not matter, for we have fit it into our own aesthetic world and conferred our own meaning upon it.

In the process of learning to see art, we also learn to tell good from bad—and the best from the good. But where did this scale of values come from? Didn’t we say at the start that we are each autonomous in matters of taste? How did it come about that we are now to judge by someone else’s lights?

More than two centuries ago David Hume took up this problem in “Of the Standard of Taste.” All responses to art, Hume’s essay argues, are fundamentally personal, but not all are equally valid. Some people are more sensitive to beauty than others. Some, better at recognizing what makes a work artful, possess sounder judgment. In Hume’s view, the man of taste possessed both sensibility and sense.

Because we have no simple means of identifying these paragons, however, they must reveal themselves by a sort of test: declare themselves “critics” and offer their judgments to the public. If they can bring others to see things as they do, they shape the current taste. In this way, by trial and error, a standard emerges. If Hume is correct about this process, as I think he is, any standard must be provisional, for it rests on nothing more solid than received opinion.

And received opinion certainly does change over time. The church of San Luigi dei Francesi stands just off a street that connects the Pantheon with Piazza Navona in Rome. If you enter the church today, you are likely to see a small crowd of people at the top of the left-hand aisle, waiting for someone to pop a euro into a metal box that will illuminate, for a minute or two, Caravaggio’s three great paintings of the life of Saint Matthew. With the striking effects of his lighting and his use of crude Italian peasants to represent the Apostles and the Holy Family, Caravaggio is today considered one of the great painters of the Western tradition. It was not always so. A century after his death, the most important guidebooks for English travelers to Rome—Edward Wright’s Observations Made in Travelling through France [and] Italy (1730) and Thomas Nugent’s The Grand Tour (1749)—made no mention of these paintings. Readers who carried either book to San Luigi would find their attention directed elsewhere, mainly to the Saint Cecelia chapel frescoed by Domenichino. As far as received opinion was concerned, Caravaggio wasn’t worth a look.

Even in his own day, Caravaggio had been controversial. One of the three paintings he originally completed for San Luigi—Saint Matthew and the Angel—was rejected by the priests who had commissioned it. In that work the saint sits cross-legged with a book on his knee as an angel directs his hand in writing the Gospel. But the saint’s naked legs and feet—with one brilliantly foreshortened foot seeming almost to protrude from the canvas—struck the patrons as below the dignity of an evangelist. Luckily for all concerned, a nobleman accepted this picture and paid Caravaggio to paint another, more decorous version of the same subject, which hangs above the chapel’s altar today. (The original version of the painting, sad to say, was destroyed in Berlin during the war.)

Despite such controversies, during the 17th century painters all over Europe followed Caravaggio’s example. But by the 18th, new ideas of propriety, even more strict than those of Caravaggio’s clerical patrons, had come to dominate contemporary taste. Raphael and Guido Reni now set the standard. The typical tourist at San Luigi was unlikely even to look into the dark chapel that housed Caravaggio’s works. It would not be until the first half of the 20th century that the Italian art historian Roberto Longhi, playing the role of Hume’s taste-shaping critic, would resuscitate Caravaggio’s reputation. Times change, tastes change. That’s the way of the world.

Received Opinion

In fact, more often than not, our initial introduction to art is an unwitting exercise in absorbing received opinion. We are likely to know the names of important artists or hear the titles of famous paintings long before we have learned to look with any sensitivity at a work of art. Who hasn’t heard of the Mona Lisa? Who doesn’t know the names Michelangelo and Van Gogh? This naturally leads us to think in terms of hierarchies, even when we haven’t seen enough paintings to tell good from bad, let alone good from great.

It is only later that a family member or a teacher will help us look, perhaps pointing out some excellence in a favorite work or introducing us to an artist that we hadn’t known before, nudging us closer to a real aesthetic experience. It was Lincoln Kirstein’s remarkable good fortune to be guided, while still in his teens, through several art shows by John Maynard Keynes. When he balked at a Cézanne, Keynes told him, “Keep your eyes open, clean of received opinion and prejudice.” It was good advice, but not without its ironies: by admiring Cézanne in 1924, Keynes and his Bloomsbury friends showed their adventurous taste. A century later, Cézanne is the darling of received opinion.

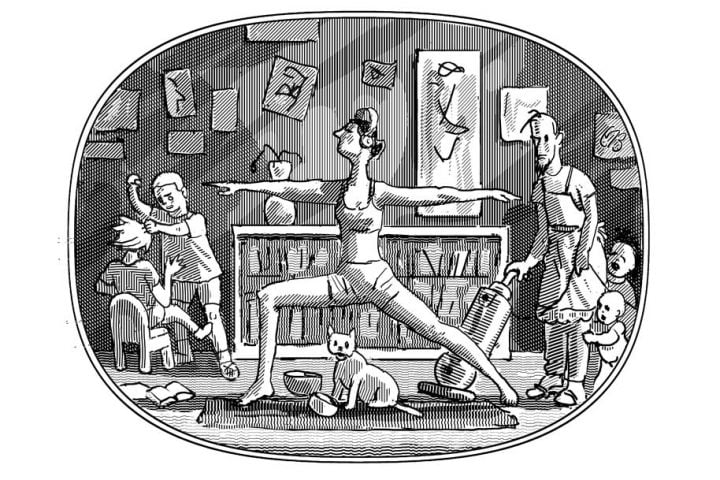

Few are so fortunate as to have a mentor like Keynes; the rest of us must be content with absorbing the taste of the time. There is no shame in that, however much we might prize independent thought, for the untrained taste is inevitably naïve. Consider a young person interested in the arts who particularly values the expression of “authentic” feeling. How is he to know what authenticity looks like in a sophisticated piece of art?

In our untutored state we are all given to what I.A. Richards called “stock responses,” the tendency to mistake commonplace but comfortable notions for real insight. In the end, even the sensitive student of art requires some direction to avoid being taken in by the flabby, the meretricious, or the merely sentimental. And if this is true of the receptive viewer, one with some affinity for the arts, what will be its effect on those with only a passing interest? At best we can hope that those who are teachable will assimilate the taste of their teachers, which in most cases will track with received opinion.

And yet, since it is only received opinion and not the art itself that one must master, even the dull can learn what to say about art without ever having been truly touched by it. Almost anyone who has taken a course in art appreciation, however insensitive, should be able to tell you of Piero’s quiet dignity or Monet’s ability to capture light. One need not truly see the paintings in order to know what to say about them. In two of his Idler essays, Samuel Johnson, a contemporary of Hume’s, gives us a humorous portrait of the fictional Dick Minim, who makes a name for himself as a literary critic by listening to the wits in the coffee houses and repeating their observations to his acquaintances. Minim knows nothing of literature, but he has learned what to say in order to be taken for a man of taste.

The same applies equally to the visual arts. Quite a few people, I am sure, have praised a Picasso or a de Kooning without having derived much pleasure from viewing it. Knowing what one is supposed to say of such works, they dutifully follow the script. Such feigning is the arty version of hypocrisy for those who want to be seen as having sophisticated taste.

The Tyranny of Experts

We are now ready to answer the questions posed at the beginning about The Man with the Golden Helmet. Before the painting was reattributed to one of Rembrandt’s students, received opinion had pronounced it a masterpiece, and those who followed the dominant taste would have agreed. These same people would likely have found it less compelling after its demotion. Those who relied on their own taste would probably reserve judgment until they could see the work again. Had they too judged more by name than by eye, they might wonder. (It is a fault hard to avoid.) Was the splendor of the helmet artful or merely showy?

Such a question, in its new context, is very difficult to answer. What one had considered genius in the master’s hand might be excess in his student’s. How is one to judge? There is no rule. One can only look, feel, and think for oneself.

The world, though, will rarely give us that leisure. We are beset by a related problem—the tyranny of experts. Let us return to the example of Caravaggio in the 18th century. The authors of the guidebooks had already determined what was worth seeing. If a visitor to San Luigi had peered into the dark chapel by chance and been deeply moved by Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, what would his contemporaries have thought? Was he a man of independent judgment or of degenerate taste? For most, I suspect, it would have been the latter.

Perhaps the most instructive example is the early history of the Impressionists. They had rejected the dominant, Academic style of painting’s formal polish and idealized subjects, searching instead for an art of greater immediacy. But their revolutionary techniques—the new, brighter palette, the loose application of paint, working en plein air—were all dismissed, even ridiculed, by contemporary critics, who largely excluded Impressionist works from the Academic salons. For decades, a Bouguereau would command a far greater price than a Monet.

Over time, however, a small group of dealers and collectors began to champion Impressionist works, giving rise to a new, dissident taste in art. The older style, which lavished its perfected technique on stale sentiment or decorative eroticism, seemed allied to the conventions and platitudes of bourgeois society. The Impressionists, on the other hand, offered vitality and novelty, the verve of the city and a countryside unencumbered with sentimentality or moral lessons—in other words, the Modern. Establishment critics now found themselves challenged by radicals and upstarts, the original avant-garde. Taste in art had become a barometer of one’s social opinions.

With a great shift in taste under way, the Impressionists had two qualities working in their favor: the paintings themselves were visually appealing, and the new aesthetic was easy to assimilate. One did not have to be a profound theorist to accept that our visual world is constructed from small blotches of color. And, once again, the paintings themselves were so pretty!

Things became more difficult, however, with Post-Impressionism and Cubism, which put new demands on the viewer. One was now expected to accept the painter’s expressionist caprice as the true source of art. If you found the work itself odd or ugly—well, whose fault was that? And with the advent of abstraction, the critics came fully into their own. Many art lovers who enjoyed the detail of a Dutch genre scene or admired a portrait by Ingres were more puzzled than moved by Jackson Pollock’s drips or Franz Kline’s swaths of black. What were they to make of such things?

A Decadent Age

Most, of course, were too intimidated to speak up for fear they would be dismissed as philistines and declared incapable of appreciating “true” or “difficult” art. The late 20th century, when the art that most pleased the experts left the typical viewer cold, was the great age of the aesthetic hypocrite. One could only wonder what someone meant when he said that he “liked” a piece of modern art. Did he find the arrangement of colors in that work, however random or chaotic, beautiful in itself? Perhaps. Was that Cubist disassembly of a female torso psychologically compelling? Maybe the first time one saw that sort of thing. Or was our viewer merely watching out for his reputation, in effect saying to himself, “Everyone knows that Matisse is a great artist, and by nodding approval I show myself a man of taste”? Our motives, of course, are often unclear even to ourselves; and who is any one of us, after all, to dispute received opinion?

At the heart of the matter is the question of who determines what constitutes refined or sophisticated taste. For nearly a century we have ceded authority in such matters not to particularly sensitive viewers of art, Hume’s tastemakers, but to intellectuals. The latter judge as their theories or their politics require, with little concern for the actual experience of looking.

Ours, sad to say, is a decadent age, in which we have allowed the critics to argue us out of our senses. (Of all the arts, music has undoubtedly suffered the most from this deference to the intellect and denial of the sensual. Does anyone outside of music schools really enjoy the latest cacophony foisted upon restive but intimidated concertgoers as “modern” music?) And yet, once again, despite the failure of much modern art to convey anything either meaningful or pleasurable to most of us, there are still many who find abstract and conceptual art compelling and who derive real aesthetic pleasure from viewing it. So malleable is human consciousness in responding to the artifice of our fellow man, and such is the power of received opinion to shape those responses.

But the tyranny of critics is hardly the greatest obstacle to a rich experience of art today. For the past half-century, the very notion of a refined taste has come under attack as oppressive, just another means by which the privileged keep down the masses. The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued that a familiarity with the arts constituted a form of cultural capital that elites employed to exclude others from the inner circles of wealth and power. Historically, there was some truth to this, especially in Europe where the pretentions of social class rested largely on the distinction of one’s ancestors. In the descendants, these pretentions manifested themselves in an arrogant demeanor and an exquisite taste.

This way of thinking, though, never made much headway in America, where successful men often took pride in their humble origins. Some self-made men, it is true, married their daughters into the European aristocracy, but if we are to trust the imaginative insights of writers like Henry James, these young Americans were alternately attracted to and repelled by their new society’s high tone yet dubious morals. In any case, the American model has come to prevail against the European one. Today, wealth and power are far more closely tied to entrepreneurial success than to a love for Mozart or one’s family pride in owning a Rubens. If a refined taste still confers any social capital, it can do so only among the few nowadays who care about such things. When was the last time that a lack of taste prevented someone from becoming rich?

What We Make of It

After all these quibbles, hesitations, and uncertainties, what finally can we say about taste? It is simply the means by which we appreciate art, especially great art. Its importance rests on two assumptions. First, that art provides valuable experiences for human beings. And second, that some of those experiences are richer and more meaningful than others.

Take music. Its popular forms today, especially rock and rap, provide an incessant accompaniment to the lives of the young. The sound is rhythmic and sensual, its pleasures emotionally exuberant and rebellious, often Dionysiac. And those pleasures are real.

Nevertheless, some of us think them shallow, expending themselves in the endocrine system. Those who dissent from the popular taste will tell you that a Bach cantata, a Beethoven symphony, or a Wagner opera can not only stir our sensual nature but penetrate to the recesses of the human heart. Modern literary theorists and cultural critics sneer at such a claim, decrying it as a form of bourgeois sentimentality or just another attempt by the well-off to justify their “privilege.” Ultimately, the question is impervious to attempts at demonstration: either you have experienced the power of art or you haven’t.

Unfortunately, our contemporary Solons talk and write as if they have never had an aesthetic experience, which, if it is in fact the case, renders them unqualified to judge. No one doubts that Game of Thrones can entertain its audience, but it cannot move us as King Lear does. The one is an amusement, the other an exploration of human vanity, ignorance, cruelty, and desire.

History, of course, is littered with moral monsters who were themselves “men of taste.” One may indeed stand open-mouthed before a Velasquez, stay awake at the opera, and shudder at the murder of Desdemona without ever doing a kindness for one’s fellow man. But this reality merely reminds us of the crooked timber of which we are made.

To live a good life, taste is neither necessary nor sufficient. It can, though, enrich our experience and, perhaps, deepen our understanding of human life. What use we make of that enrichment and that deepening is up to us.