At least since the Viennese art historian Alois Riegl coined the term Kunstwollen or “will-to-form” over a century ago, scholars and curators have been increasingly inclined to evaluate works of art in period terms, without regard to aesthetic norms or standards of technical competence transcending particular historical contexts. For Riegl (1858–1905), each age must generate its own notions of beauty and truth in art; otherwise the age could not express itself. Since his time, art history has put the emphasis decisively on history, understood as an ongoing process of changing artistic intentions.

The orthodoxy Riegl helped establish knocked the classical tradition, itself based on the imitation of nature through objective forms and standards, off its pedestal, making room for the fulsome appreciation of art once regarded as bad or inferior—for example, that of late antiquity, which happened to be a specialty of Riegl himself; or the primitive art of aboriginal cultures. But recent exhibitions at New York’s Frick Collection and Washington’s National Gallery of Art suggest how impoverished art history has become in the absence of abiding standards of achievement. These important exhibitions included a lone sculptural masterpiece from the Capitoline Museum in Rome, the Dying Gaul; a panoply of Byzantine art from Greece; and drawings by the young Picasso, both during and after his formal training in Spain.

Art Unsurpassed

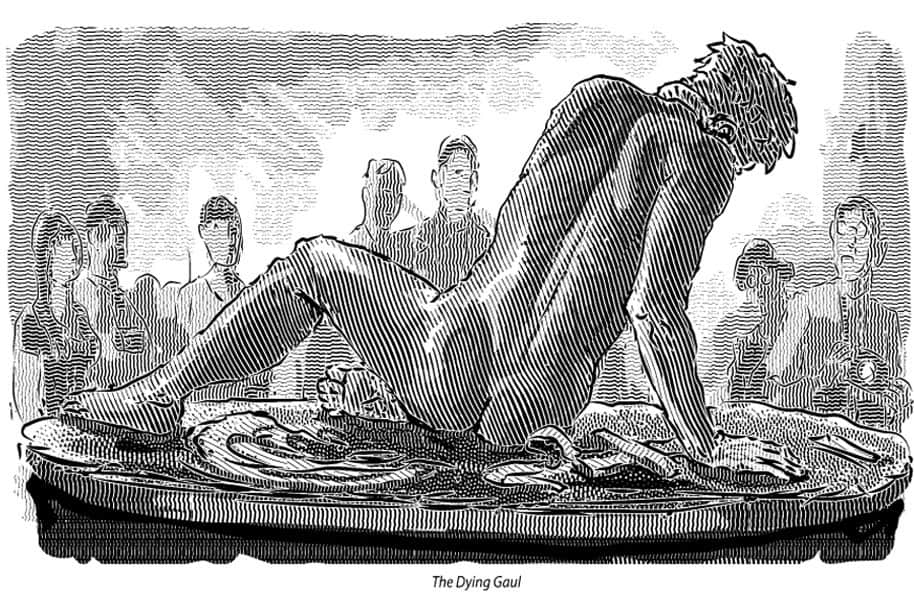

The Dying Gaul was on view in the National Gallery’s West Building rotunda throughout the past winter. A superb ancient marble copy of a lost Hellenistic bronze dating to around 200 B.C., it portrays a fallen nude warrior with a mortal wound in his flank, propping himself up on one arm, his other arm extended forward with the hand perched on his thigh, his head bent toward the ground. This life-size, subtly torsional sculpture’s brilliance lies in the way it seemingly unwinds into our perceptual space while drawing us towards it like a magnet. Nothing about the Celtic warrior seems static, for energy visibly suffuses his lithe body even though he is breathing his last. The arrangement of his bent arms and legs creates divergent planes projecting out from the torso so as to compel the spectator to take him in from different angles. The sculptor masterfully calibrated the geometry and proportions of the anatomical forms so that the Gaul conveys a sense of organic wholeness, but without compromising on the articulation of the human body’s structural complexity. The resulting topography leads the eye in countless trajectories around the figure, thus reinforcing its spatial presence. This sculpture’s powerful aesthetic effect is essentially unpictorial and involves what we might call the geometric conquest of its environment.

Since ancient times the Greek achievement in fine art has been taken to lie in its unprecedented naturalism. But as the Dying Gaul attests, naturalism is only part of the story. Of course the Greeks consciously sought a life-likeness lacking in the art of earlier civilizations, but they went far beyond this. Their archaic statues first evolved into life-like and, after that, spatially continuous figures. By “spatially continuous” I mean that they were designed to counteract, or override, the natural pictorial mechanism of human vision whereby we see the world around us not in three dimensions, but as a two-dimensional picture generated by the reflected light that the lens of the eye projects onto our retinal movie screen. Monumental Greek sculpture thus overcame nature the better to represent nature; it attained an intensified physical presence that distinguishes it from merely naturalistic, pictorially-oriented art. The British Museum’s majestic pedimental figures from the Parthenon epitomize this quest for a fully dimensional sculpture, as does the Dying Gaul.

Greek sculpture of the classical and Hellenistic periods set a standard that Western art has never surpassed. It also stands apart from the fine art of any non-Western civilization precisely because of its unpictorial character. High-quality classical sculpture, mainly in the form of copies, continued to be produced well into the Roman imperial period. But the elevated level of conceptual knowledge and manual skill it entailed couldn’t be sustained indefinitely, and by the time of Constantine the Great sculpture had regressed dramatically. Of course we’re not supposed to say that. Negative appraisal of another culture’s Kunstwollen is bad form. Among other things, it calls into question the relativism that governs contemporary art-historical scholarship.

Vestiges of Greatness

This brings us to Heaven & Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, which coincided with the Dying Gaul’s display at the National Gallery before moving on to the Getty Villa in Malibu, California. This vastly informative exhibition included a number of examples of sculpture from late antiquity—that is, the period preceding the Byzantine artistic canon’s emergence in the 6th century. The portrait bust of a young woman from Asia Minor, thought to date to around 400 A.D., was conceived in hapless emulation of classical form. The woman sports an elaborate headband with her braided hair laid up in horizontal tiers above it. But her smooth cheeks are misaligned, with one quite conspicuously recessed behind the other, and this causes a distorted alignment of the mouth. Her drapery is simplistically designed and there is not the slightest indication of breasts beneath it, so that her chest might as well be a boy’s. This is, at best, deeply flawed sculpture. Not even the exhibition catalogue, however, acknowledges this obvious fact. It is just not done.

In contrast, the more or less contemporaneous bust of a heavily bearded man of late middle age, draped with a toga, strikes a distinctly expressionistic tone. The man’s hair—neatly trimmed above the forehead, thick and tousled on the sides—could be a philosopher’s. The large, protruding ears and bird’s-beak nose verge on caricature, but what seizes one’s attention are the eyes popping out as though he were in a trance. In this bust we find none of the supple, complex modeling of facial shapes we see in Hellenistic portraiture. Instead the sculptor relies mainly on the play of light and shade on more or less vigorously incised patternizations of hair, beard, cheeks, eyebrows, eyes, drapery, and so on. Had the unknown Attic sculptor of this bust, who was presumably familiar with the Parthenon sculptures and other classical wonders, consciously adopted a new method in place of the one that had vanished? It’s entirely possible. What we can say with certainty (though art historians are quite unlikely to say it) is that, as in late-antique sculpture generally, a dimensionally-oriented method of representation had been supplanted by a much more simplistic, pictorially-oriented one, the artist’s natural tendency given the pictorial mechanism of human vision.

Unlike the partly pagan world of late antiquity, Byzantium was wholly Christian. At the same time, Byzantine imperial, clerical, and municipal elites were well-versed in classical literature, and the memory of an earlier age permitted the display of antique works in secular settings. Leaving aside Pheidias’s vanished freestanding gold-and-ivory statue of Athena, even the Parthenon’s sculptural decoration was left intact when it was converted into a church, probably in the late 5th century. Still, hardly any of the bronze cult statues that set the standard for classical and Hellenistic art have come down to us. Many an irreplaceable masterpiece surely met its end at the hands of Christians who considered the visceral sense of presence it conveyed demonic.

Sculpture in the round found no place in Byzantine sacred art, whose definitive creation is antique sculpture’s pictorial and spiritual antithesis, the icon: the schematic, frontally-posed image of Christ, Virgin, or saint, rendered in mosaic, fresco, or tempera and set off against a lustrous, often golden, background. Far from projecting majestically or demonically into the viewer’s perceptual world like a classical statue, the icon beckons from a heavenly sphere beyond space and time. Though its flesh and drapery folds are modeled to a degree with light and shade, its form is defined mainly through linear patterns. The icon was passed down from generation to generation as an unchanging hieratic type in a manner more characteristic of Egyptian art than Greco-Roman. It was deployed not only in architectural decoration but also in portable formats. Because it radiated a protective power from its heavenly realm, the icon might even be carried into battle like a banner.

Byzantine sacred art thus betrays less of the stylistic variety we encounter in late antique work. Nevertheless, classical formal traits, though vestigial, are not insignificant in Byzantine art. The drapery of a male saint in a mosaic composition might be elaborately designed to provide a volumetric sense of the body underneath, thus enabling the saint, however awkward his anatomical construction, to wear the drapery rather than vice-versa. And as time wore on, icons in the form of painted panels assumed greater pictorial complexity, with less static figures and more elaborate architectural or landscape settings, while still retaining much of their unnaturalistically schematic character.

The art of panel painting had largely disappeared in the West after the fall of the Roman Empire, while formally unsophisticated sculpture was profusely employed in the decoration of churches from the Romanesque period onward. But increasing commercial and cultural interaction with Byzantium eventually led to panel painting’s resurgence in Italy. Byzantine sacred art thus set the stage for early Renaissance masters like Cimabue and Giotto, providing a conceptual framework which their successors modified by incorporating more realistic modeling and perspective into their method. A parallel development in sculpture led to Donatello’s refined medieval realism.

Recovery and Continuity

But the greatest Renaissance artist of all—and arguably the greatest Christian artist of all—eschewed the pictorial orientation which the medieval art of both eastern and western Christendom had bequeathed to the Renaissance. It was the discovery, in Rome, of the superb Hellenistic torso, the Belvedere Torso, that inspired the supremely sculptural male nudes, or ignudi, arrayed on Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling. Along with his sculptural masterworks, such as his majestic Medici Chapel figures at San Lorenzo in Florence, that mural resulted from a direct re-engagement with antique principles of form. These principles, then, were not only relevant to sculpture. Nor were they narrowly prescriptive. They shaped the work of painters as divergent in style and sensibility as Rubens and Caravaggio.

So there is a vital continuity between the great works of antiquity and the modern age that dawned with the Renaissance. It is this continuity which art exhibitions too often fail to emphasize, mainly because our curators habitually relegate art to period pigeonholes. For example, in the same National Gallery rotunda where the Dying Gaul was displayed, a bronze Mercury derived from Giambologna’s original of about 1580 crowns a magnificent fountain. The nude, helmeted god dashes across space, his left foot poised on the sculpted breath emanating from the head of a putto, which faces straight up. The god’s supple musculature is modeled so that the eye dances around this serpentine figure. He points upward with his raised right hand while bearing his caduceus, or snake-entwined staff, in his left arm. This arm, somewhat pulled back from the torso, generates a subtle twist in the figure that is counteracted by the turn of the head in the opposite direction. The bent right leg and arms and even the extended forefinger and thumb of the raised hand generate divergent planes that, along with its torsional dynamic, reinforce the dimensionality of the slightly less-than-life-size sculpture and allow it to expand into the enveloping space. This Mercury belongs to a more stylized genre than the Dying Gaul, but it was quite obviously conceived along analogous lines. Which is not surprising, insofar as the Flemish-born Giambologna (1529–1608) migrated to Florence and was deeply influenced by both Hellenistic sculpture and Michelangelo, who instructed him to focus on the human figure’s inner structure rather than surface detail. But it is doubtful one National Gallery visitor in a thousand who saw the Dying Gaul noticed the very significant kinship between these two works.

Need for Standards

Apart from intellectual sea-changes in the 19th century, one technological innovation contributed very generously to classicism’s eclipse. This was the photograph, a mechanically-produced optical record of the visual world in which that world is reproduced in gradations of light and shade, with color eventually supplementing the record. The French academicians welcomed photography, which degraded their training and consummated the human figure’s transformation from a thing-in-itself of immense geometric complexity into an increasingly simplistic, pictorial byproduct of light and shade. As a result, Cézanne’s celebrated “modernist” advice to a younger painter to treat nature by means of rudimentary geometric forms—the cylinder, cone, and sphere—conformed to the academic practice of his day.

An exhibition of Picasso’s early drawings at the Frick and National Gallery in late 2011–early 2012, Picasso’s Drawings: 1890–1921, demonstrated Cézanne’s dictum in action—for instance, in Picasso’s charcoal drawing, while a 13- or 14-year-old Wunderkind at the Barcelona academy, of a plaster cast of the reclining Ilissus figure from the Parthenon’s west pediment. Picasso rendered this nude figure’s left shoulder—a magnificent, highly complex form—as a dumb, almost spherical shape. A widely disseminated, late-academic drawing primer from which he made a number of copies, the Cours de dessin (1868–1871), encouraged him to do precisely that. It is no coincidence that the academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme collaborated on the Cours: any number of his historical, mythological, and genre scenes are saturated with a photographic aura. The upshot is that a crucial thesis underlying the Frick-National Gallery exhibition—that the academic training Picasso underwent “had remained relatively unchanged since the Renaissance,” to quote the catalogue introduction—is simply false. Not surprisingly, the catalogue doesn’t even mention Picasso’s amply documented use of the Cours de dessin. The icing on the cake is that it puts Picasso on the same plane as Michelangelo by describing each as “one of the world’s greatest draftsmen.” The reality is that Picasso did not have access to truly classical training. And however extraordinary his native talent, he was an incompetent draftsman by comparison with Michelangelo. Picasso’s decidedly eclectic oeuvre thus amounts, like one of his Cubist paintings, to a collage of pictorial fragments.

Of course, by the time Picasso came of age at the turn of the last century, objective criteria of technical competence could not be permitted to undermine modernity’s, or the modernist artist’s, self-esteem. Riegl’s Hegelian Kunstwollen soon found its mythopoeic counterpart in a Nietzschean will-to-form that exalted the Promethean genius who forged a radically new art amidst the shattered remnants of tradition. Picasso himself thus became the object of a Nietzschean personality cult that endures to this day, while reaping enormous benefit from the relativist revision of art history by Riegl and his successors. That revision opened the door to highbrow appreciation of Picasso’s resort to crude stylizations evoking the “primitive.” The impetuous Spaniard would surely have found more inspiration in that expressionistic, exophthalmic male portrait bust from late antiquity than in a far more skillful portrait by a Hellenistic master, or by a modern master like Houdon.

The Frick and National Gallery exhibitions, like just about any exhibition you walk into these days, demonstrate that we no longer have a reliable scholarly gauge of artistic achievement or technical competence. We have dire need of a pedagogy, both art-historical and strictly artistic, divorced from that Romantic shibboleth, Kunstwollen. We need a pedagogy capable of situating the Byzantines’ very significant artistic achievement in its proper relation to the classical achievements that preceded and followed it. We need a pedagogy that enables us to see through the vulgar personality cult perpetuated by the Picasso’s Drawings exhibition and countless others like it. Finally, we need a pedagogy that challenges pupils to understand that classicism really does not conjugate as a style, but as a distinct way of seeing nature—and the human figure above all—that has manifested itself in a variety of styles and genres over a very long period of time, immeasurably enriching the cultural patrimony of mankind.

Classical discipline, properly understood, involves a grasp of form that is unnatural in terms of the way we are hardwired to see the world, and therefore conducive to representing nature in a way that transcends our ordinary experience of the world. This doesn’t mean human modes of perception are irrelevant to classical representation. Nothing could be further from the truth. The point is that the classical standard has its origins in the Greeks’ abiding awareness that what we see and what is are two different things. It originates, in other words, in reality.