Books Reviewed

A review of The CONSERVATIVE FOUNDATIONS OF THE LIBERAL ORDER: Defending Democracy against Its Modern Enemies and Immoderate Friends  , by Daniel J. Mahoney

, by Daniel J. Mahoney

This brief, approachable book, intended by its author "to be a learned essay that is accessible to citizens as such," contains sharp historical insights and intelligent comments and interesting biographical details on the writers it discusses. Its basic argument is that modern, liberal democracy cannot survive without "pre-liberal" and "extra-liberal" political and cultural traditions, which are under siege. A liberal democracy without these "conservative foundations of the liberal order" would not be a durable "order," for liberty without its "conservative" foundations—which means respectable and respected hierarchies that withstand the urge to democratize everything—is (by definition, I suppose) bound to fail.

In the preface, Daniel Mahoney, a professor of political science at Assumption College and CRB contributor, summarizes his central concern:

Democracy is prone to corruption when its principle—the liberty and equality of human beings—becomes an unreflective dogma eroding the traditions, authoritative institutions, and spiritual presuppositions that allow human beings to live free, civilized, and decent lives.

He states this concern more bluntly and clearly in a recent interview about his book in The University Bookman (Winter 2011):

It is a great illusion to think that liberty is identical with unencumbered choice and a reckless disregard for the wisdom of the past. The book is a reminder that democratic liberty can only flourish when it freely acknowledges the "continuity" of civilization—the debt of liberty in the modern world to classical and Christian presuppositions that we are increasingly tempted to disregard. I am in no way an enemy of the liberal order. But I hope to make my contemporaries more aware of the dependence of what is most valuable in liberal democracy on "conservative foundations" that it doesn't sufficiently acknowledge and sometimes actively undermines.

Mahoney defends liberal democracy against its modern totalitarian enemies on the Left and the Right, but also—and more urgently and passionately—against its wrongheaded friends: those who unwisely try to undermine modern democracy's foundations in Western political and cultural (particularly religious) traditions. These more insidious enemies are dedicated to freeing us from the constraints of those traditions, and are all the more dangerous because they can plausibly present themselves as democracy's more consistent defenders. In fact, Mahoney himself accepts that they are indeed more consistent.

These "immoderate" (and false) friends define democracy and democratization as the maximum increase in individual emancipation and autonomy, and they apply this abstract theory of democracy in a destructively demanding way. Although Mahoney sees this destructive theory flourishing throughout the West since the cultural revolution that began in the 1960s, he also finds an unhealthy abstraction from political and cultural inheritances in liberal thinkers going back as far as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. (For Mahoney, as for Edmund Burke, abstract theory is generally bad theory.)

* * *

Part one of the book—its "theoretical core"—is called "The Art of Loving Democracy Moderately." To love democracy "moderately" is the contemporary French political thinker Pierre Manent's characterization of Alexis de Tocqueville's advice to liberal democrats. Those who love liberty passionately (that seems to be permitted) but wisely will love democracy only moderately. They will be "chastened liberals." Mahoney follows Tocqueville's (and Manent's) advice to adopt "a sober and qualified appreciation of democracy." This means recognizing "the threats that unbridled democracy" poses to "the freedom and integrity of human beings"; "never losing sight of the fact that the recognition of the equality of human beings can never substitute for the cultivation of the ‘grandeur,' ‘independence,' and ‘quality' of the human soul"; and being deeply concerned with the maintenance of the "pre- or extraliberal traditions and habits" that are essential to the health of liberal democracy, but are endangered by the mistaken belief in the self-sufficiency and self-sovereignty of individuals, a belief that democracies are irresistibly tempted to adopt.

It is from this position that Mahoney would have us confront the destructive "radical" or "abstract" theory of democracy that is currently advocated by many intellectuals (up to now, more effectively in Europe than in the U.S.), who succumb to what Mahoney calls in part three of his book "The False Allure of ‘Pure Democracy.'" This "corruption or radicalization of democracy" became prominent in the 1960s with the New Left's challenges to liberal democracy sensibly understood. Today's partisans of "pure democracy" (another expression that Mahoney takes from Manent) are the "immoderate friends" (actually the "worst enemies") of democracy.

The defining moment for these advocates of "pure democracy" was 1968. Yet this moment did not coincide with the widespread protests against liberal democracies' unjust hierarchies and political actions, for these protests had little deep practical impact at the time, and some well-founded objections to and corrections of the rigidities of the traditional social order had appeared before 1968.The real turning point in 1968 arose from the excessive and paradoxically authoritarian way these objections and corrections were pursued thereafter, and in the radicalization of democratic theory that justified these practical excesses. "Nineteen sixty-eight was the moment when democracy became self-consciously humanitarian and postpolitical and therefore broke with the continuity of Western civilization." The civic equality that is "at the heart of democratic political life" has become "the unchallenged model for all human relations." Moreover, "a laudable respect for the accomplishments of different cultures has given way to an absolute relativism that denies the very idea of universal moral judgments and a universal human nature."

Before 1968, the new and old dispensations—liberal democracy and "older moral traditions and affirmations"—had "coexisted without too much (practical) difficulty." But a profound theoretical conflict existed nonetheless, papered over by a temporary alliance of liberals and conservatives. Opposition to 20th-century totalitarianisms had enlarged the common ground of liberals (who "rediscovered the moral law at the heart of Western civilization") and conservatives ("churchmen discovered the virtues of liberal constitutionalism"). But "1968 shattered this anti-totalitarian consensus and gave birth to "postmodern democracy." More precisely: "Nineteen sixty-eight played a central role, as both cause and effect," in the "reduction of a capacious tradition of liberty to an idea of democracy committed to a single principle: the maximization of individual autonomy and consent." Mahoney concludes from this that one important lesson of 1968 is that "the idea of democracy is never sufficient unto itself," and that as "pure abstraction or ideology, democracy risks becoming a deadly enemy of self-government,…human liberty and dignity."

* * *

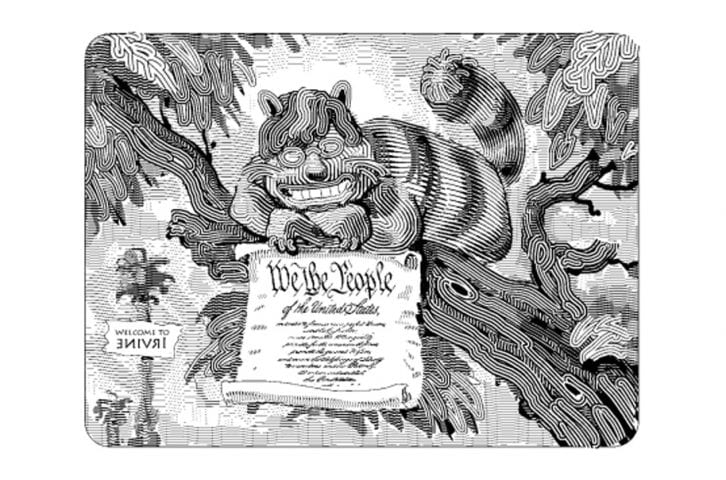

Mahoney calls on many European thinkers and statesmen and a few American ones to help him define, and defend, modern liberal democracy. The book's front cover features portraits of four of his heroes: Burke, Winston S. Churchill, Alexis de Tocqueville, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Between the book's covers we encounter Burke's "defense of tradition and practical reason" against ideological abstractions, Churchill's thoughts on democracy's limitations and the dangers of mass society, Solzhenitsyn on the fragility of the Enlightenment principles of modern liberalism and the shortcomings of "anthropocentric humanism," Michael Burleigh on terrorism, Raymond Aron on totalitarianism and conservatism, and of course Tocqueville on practically everything.

When Mahoney briefly discusses the American Founders (in fewer than three pages), it is mainly to argue that they "built better than they knew," for their thinking "presupposed a ‘hodge-podge anthropology' [Mahoney is quoting Walker Percy] that drew unevenly upon classical and Christian wisdom, on the one hand, and Enlightenment propositions, on the other." Although this was a "fruitful tension," it was "also an unstable mixture that was likely to decay as time went on." It is not clear why.

He therefore argues that "the founders' practical achievement was in decisive respects better than their theory." Therefore, particularly when it comes to opposing "willful claims on behalf of human autonomy," Mahoney suggests we should "remain faithful to the ‘genius' of the founding while moving beyond the founders' somewhat constricted theoretical horizon." He complains that their endorsement of social-contract theory was inferior to Tocqueville's more historical—sociological approach, and conspicuously lacked the Frenchman's appreciation of the danger that this abstract theory would be harmfully applied to "every aspect of human life."

For Mahoney, the genius of the founders lay not so much in their political theory as in the practical wisdom that led them (unlike some of the French revolutionary leaders) to avoid starting from scratch, and to respect as a historical given "America's unwritten or ‘providential' constitution," i.e., "the habits and mores of the American people so eloquently described by John Jay in Federalist 2." So much for Publius's improved science of politics! Therefore—with help from Tocqueville and others—"it is up to us today to theorize [the founders'] practical wisdom and thus transcend the limits of some of their theoretical assumptions and presuppositions."

Why does Mahoney not find the founders' mixture of ancient and modern a commendable instance of the continuity of Western civilization, rather than an unstable hodgepodge? Perhaps it is because he fails fully to take into account the deep differences between radical, nihilistic moderns (with Hobbes, Rousseau, and Hegel at the cutting edge), and moderate moderns (e.g., Locke, Montesquieu, James Madison, and John Stuart Mill), who see far less opposition than radical moderns do between nature and good human lives. (For example, unlike the founders, Mahoney often refers to the political theories of Hobbes and Locke as if they taught fundamentally the same things.) And though Mahoney does notice that the Enlightenment was "more variegated" than Solzhenitsyn suggests—"not all of its currents succumbed to atheistic fanaticism"—the author's odd example of a "radical commitment to ‘liberation'" is Jefferson's denunciation of the "monkish ignorance and superstition" (Jefferson's words) that had been used to support oppressive governments. Or perhaps Mahoney does see the depth and importance of the distinction between radical and moderate moderns, but simply fears that the moderates are less viable than the radicals, and hence we need to boost the influence of traditional culture and religion, which to Mahoney means Christianity, in order to combat the power of the radicals' appeal.

* * *

However that may be, the downsides of democracy were hardly unknown to the founders, whose writings are full of warnings about them. Nor did recognition of the social and intellectual excesses of democracy—such as those referred to in Plato's dialogues and Aristophanes' plays—have to wait for Tocqueville's brilliant analyses.

As good moderate moderns, the founders would surely have agreed with Mahoney's fine statement about the most fundamental issue of liberal democratic politics: "The law cannot be fully ‘neutral' about the good life—about the ends and purposes of human life—without eventually subverting the idea of human nobility and the moral foundations of liberty itself." And the founding generation—and later generations even more—found in the modern emphasis on natural human equality (even though it is, as Abraham Lincoln observed, "an abstract truth") the basis of an ethics that respects respectable hierarchies, without needing so much recourse to the pre- or extra-liberal inheritances that Mahoney insists upon. That may help explain why, as he notices, hyper-democratization has affected Europe more than the United States—in spite of Europe having more old-regime survivals. Why should trying to boost pre-liberal or extra-democratic forces here at home be more effective than cultivating Americans' liberal democratic ethics, in theory and in practice?