Book Reviewed

Night after night, Fox primetime host Tucker Carlson roasts America’s failed bipartisan establishment, exposes corporate and government malfeasance, and reassures millions of Americans that, no, they haven’t lost their minds—it’s elites who are gaslighting them: the generals who fret about “white rage” while abandoning top-shelf military equipment to the Taliban; the epidemiologists who ban outdoor religious gatherings while practically requiring attendance at Black Lives Matter riots; the tech moguls who censor lawmakers for daring to suggest that “Admiral” “Rachel” Levine isn’t a woman; the woke gazillionaire whose delivery drivers are forced to relieve themselves in bottles for lack of breaks; the “conservative” editors and think-tankers who haven’t conserved a single thing.

Carlson keeps them honest and the rest of us sane. He reports seriously and thinks deeply. His monologues are superbly crafted. And he is genuinely funny. Viewers wondering how Carlson came to be such a talent should look no further than The Long Slide, a new anthology of his magazine journalism spanning the late-1990s to the dawn of the Trump era. The upshot: Carlson’s success as a broadcast man is at least partly rooted in his talent as a print writer.

* * *

The book is worth the price of Carlson’s new introduction alone, in which he takes his own publisher, Simon & Schuster, to task for its political bias. As he relates, the pieces collected here are relics of a bygone age of magazine journalism: a time not too long ago when the nation’s leading magazines, including liberal ones, were prepared to give a hearing to anyone offering fresh facts, sound arguments, and limpid prose—even Tucker Carlson, whose magazine work offered all three in spades. He got his start as a fact-checker for Policy Review and then worked as an opinion writer for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, before landing a job as a staff writer with the Weekly Standard when it was founded in 1995. From there he worked as a columnist for New York magazine and Reader’s Digest. As recently as 2016, Carlson was placing essays and reportage in the likes of Politico, Esquire, and the old New Republic, outlets that would never publish him today, as he admits. Which is their loss. Because these articles radiate the same sense of humor, concern for the underdog, and disdain for elite bull-pucky that are hallmarks of his TV show—but the nature of the print medium allows him to go much deeper.

Consider the opening essay, a 2003 dispatch from Africa for Esquire magazine. Carlson’s travel companions: the Reverend Al Sharpton, Cornel West, and a coterie of black nationalists, launching an inspired if cockamamie plan to end the civil war in Liberia. The setup is priceless, of course, but a less capable writer would have leaned too heavily either in the direction of satire or African civil war pathos. Carlson largely takes an understated show-don’t-tell approach. His humor is subtle. “It struck me as a fine idea,” he recalls, as Sharpton forms a prayer circle five minutes after Carlson is briefed on the dismal state of Ghana Airways’ fleet; elsewhere, he observes, “I didn’t meet anyone affiliated with [the militant group Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy] who didn’t look as if he’d just returned from a long but enjoyable day of summary executions.”

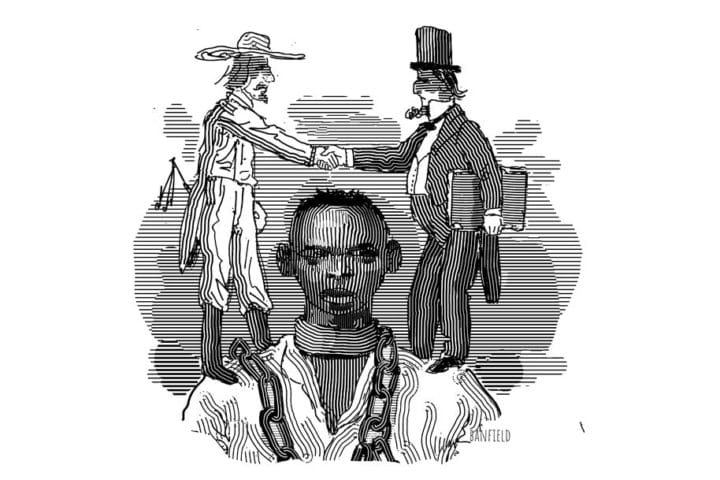

The pathos, meanwhile, builds gently before overflowing. One of the black activists in the group keeps needling Carlson throughout the trip, pressing him to atone for the sins of his white ancestors. Ahead of a visit to a slavery museum, he warns Carlson, “I’ll be watching you when we get there. I want to see if you even cry.” After days of such taunting, Carlson yearns to smash the guy in the face. “The idea that I’d be responsible for the sins”—or the glories—“of dead people who happened to share my skin tone has always confused me.” In the event, the visit to the slavery museum—a converted dungeon once used to hold Americas-bound slaves—turns out to be cathartic and healing, though Carlson’s tear ducts remain dry. At the end, his erstwhile tormenter tells him, “I love you, man.”

* * *

Although most of the essays predate Donald Trump’s rise to power, they contain revealing hints as to why Carlson, once a “mainstream” conservative, would come to embrace Trumpian populism. A New Republic profile of Ron Paul is notable for Carlson’s sympathetic portrait of the left-behind Americans drawn to the libertarian representative’s gold-buggery (sorry, couldn’t resist). Writing amid the Great Recession of 2008-09, Carlson wonders, “If the gold standard is crazy, is it really any crazier than hedge funds?”

Then there’s his barnburner of a January 2016 Politico essay that successfully predicted Trump’s staying power in the GOP primaries (this, while many other right-of-center pundits tried desperately to wish-cast The Donald away). It deserves quoting at some length, because it foreshadowed many of the intra-Right hostilities—er, debates—that would dominate the Trump and post-Trump eras. Of the conservative think-tank-industrial complex, Carlson writes,

Over the past 40 years, how much donated money have all those think tanks and foundations consumed? Billions, certainly…. Has America become more conservative over that same period? Come on. Most of that cash went to self-perpetuation: Salaries, bonuses, retirement funds, medical, dental, lunches, car service, leases on high-end office space, retreats in Mexico, more fundraising. Unless you were the direct beneficiary of any of that, you’d have to consider it wasted.

Likewise, Carlson gets to the heart of still-flaming tensions between Republican elites and the GOP’s increasingly working-class base. Here he is—again, writing in early 2016—on the Never Trumpers’ moral henpecking of the base:

The people doing the scolding? They’re the ones who’ve been advocating for open borders, and nation-building in countries whose populations hate us, and trade deals that eliminated jobs while enriching their donors, all while implicitly mocking the base for its worries about abortion and gay marriage and the pace of demographic change. Now they’re telling their voters to shut up and obey, and if they don’t, they [the voters] are liberal.

The Long Slide is, above all, a reminder that Carlson is a good writer—a damned good writer. Here’s the lede that opens a profile of Mike Forbes, a standard-issue-conservative congressman from Long Island best remembered for his quixotic decision to become a Democrat in 1999, the year Carlson wrote about him for the Weekly Standard: “Mike Forbes likes soup. But he doesn’t like corn. So when Forbes…found corn in his dehydrated soup-in-a-cup, he had a member of his congressional staff remove every kernel.”

Tucker is an American original. May he keep going from strength to strength.