Books Reviewed

In 1794 president George Washington wrote to Vice President John Adams on the necessity of assimilating immigrants to the new American republic’s way of life. Presciently, Washington lamented the prospect of immigrant ghettos and, as Americans would say two centuries later, multiculturalism. Settling immigrants “in a body,” Washington wrote, meant that “they retain the Language, habits, and principles (good or bad) which they bring with them. Whereas by an intermixture with our people, they, or their descendants, get assimilated to our customs, measures and laws: in a word, soon become one people.”

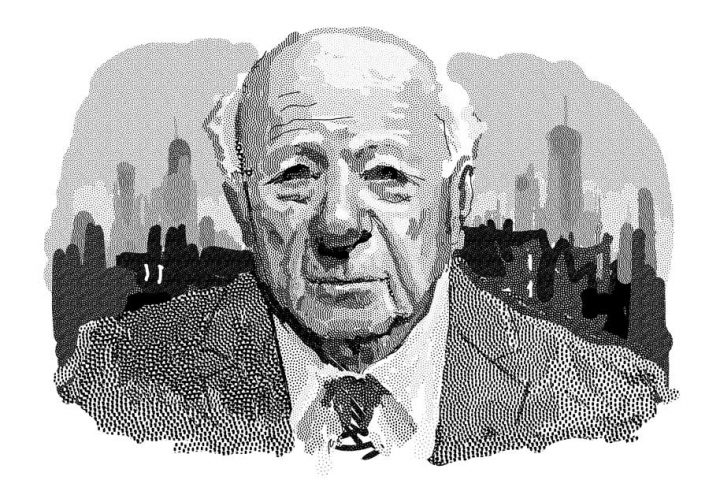

Two hundred twenty-four years later, a son of Bangladeshi immigrants makes a similar argument in the modulated language of social science. Reihan Salam’s Melting Pot or Civil War? is one of the best diagnoses of immigration policy in the past decade. The best prescription, however, remains Mark Krikorian’s The New Case against Immigration (2008), also published by Sentinel.

Drawing on high-quality and ideologically diverse research, Salam, a former executive editor of National Review who in February became the new president of the Manhattan Institute, presents an empirically grounded critique of our current immigration policy. “High levels of low-skill immigrants,” he states, “will make a middle-class melting pot impossible.” The current system fosters inequality, has increased the poverty rate, and keeps a large section of our economy in a “low-wage, low-productivity rut.” What most concerns him is whether low-skilled immigrants’ children will assimilate.

Salam says that the crucial question concerns the type of assimilation: “amalgamation” or “racialization”? Will the children of newcomers enter a new “melting pot” and adopt the “culture and folkways of the established population,” entering the fabric of America “through ties of friendship and kinship”? Or will they grow up in “immigrant enclaves,” socially distant from mainstream America and “relegated to second-class status.”

Unfortunately, “[n]ot everyone is assimilating into the same America.” Many “are being incorporated into disadvantaged groups” and “often feel alienated from the mainstream.” As a result, “We are entering such a dangerous moment.” The National Academy of Sciences (NAS), Salam reports, determined that 45.3% of immigrant-headed households with children relied on food stamps, compared to 30.6% of native-born households with children. The NAS study also declared that not only first-generation immigrants, but also their children and grandchildren, were “net fiscal burdens” for the nation.

From Salam’s well documented critique of how our immigration policy actually works, we can draw significant conclusions, ones that Melting Pot or Civil War? implies rather than explicates. First, the argument advanced by prominent Republicans as well as Democrats that the assimilation process is intact is deeply flawed. Today’s immigrants and their children, we are told, are assimilating as quickly and thoroughly as the previous waves of immigrants in the days of Ellis Island. Hence, we needn’t worry about a Balkanized America: the children of today’s Mexican and Central American immigrants will assimilate just like those who arrived more than a century ago from southern and eastern Europe.

* * *

Salam wryly notes that when Israel Zangwill’s play The Melting Pot was first performed in 1908 there “wasn’t much of a melting pot.” Instead, many immigrants lived in “flourishing ethnic enclaves, which were regularly replenished by new arrivals.” There they retained their own customs and languages in a social world disconnected from the American mainstream. Not until the “immigration restriction legislation of the 1920s” did the “melting really begin in earnest.”

In other words, restricting immigration promoted Ellis Island-era immigrants’ patriotic assimilation. Since the Italian and eastern European enclaves were not restocked by perpetual streams of new arrivals from the Old World, immigrants and their children eventually left the ethnic neighborhoods, married outside their ethnic group, and joined the middle class. In contrast, Mexican and Central American enclaves are continually reinforced by new immigrants, hindering the assimilation of newcomers and their offspring already in the United States. Salam notes that when his parents immigrated there were very few co-nationals from Bangladesh living in New York, precluding a childhood in an ethnic enclave that almost certainly would have put his professional and personal life on a very different course.

Another major difference between the 1920s and today is the nation’s economic structure. When low-skilled jobs were a significant part of the economy, the pay differential between immigrants and the native-born among the low-skilled was smaller than it is today. The problems connected to mass low-skilled immigration that Salam outlines have become more recognizable. Yet, many conservatives still advocate for more immigration and, in particular, more low-skilled workers. When he was Speaker of the House of Representatives, Paul Ryan declared that “I always look at [immigration] as an economic issue.”

But, we are a nation, not simply a market. This employer-first reflex by some on the Right disregards what is at stake in the entire immigration-assimilation issue. Most importantly, it fails to recognize how liberals use mass immigration accompanied by weak or multicultural “integration” to advance progressivism’s ultimate goal, the “fundamental transformation of the United States of America.” The combination of mass immigration and weak assimilation must be understood in terms of the broader conflict that Angelo Codevilla describes as a “cold civil war” being waged “against a majority of the American people and their way of life.” Indeed, more than 20 years ago, Norman Podhoretz envisioned an aggressive “liberationist” nation assaulting the culture of the “traditionalist” middle-class American nation.

* * *

Recently, Tom Klingenstein of the Claremont Institute explained the struggle between America, as the founders and Lincoln understood it, and an adversarial multiculturalism that seeks to replace the American regime with an entirely different, group-based system constructed on different political principles. (In much the same way, the Confederacy was built on different principles than those of the Declaration of Independence.) These are the stakes in setting immigration policies and an assimilation ethos. (Elsewhere in this issue, Klingenstein expands his argument to sketch a new political approach.)

In the progressive framework, immigrants are assimilated into an ethnic-linguistic-cultural subgroup within a broader multicultural system. This agenda was made explicit in Obama Administration policy documents that directed that English competency and assimilating to American culture should not be “prioritized” for the children of immigrants. Instead, the “maintenance” of their parents’ native (foreign) culture and language was emphasized. For example, one document recommended that Somali-American children should be “encouraged” to use their home language and that Islamic Somali culture should be maintained.

* * *

For salam, “diversity is not the problem.” Rather, “[w]hat is uniquely pernicious is extreme between-group inequality.” That said, I would assume that Salam would agree that the ideology of “diversity,” or what John Marini calls “a new kind of civil religion” is, indeed, intellectually dubious and socially detrimental.

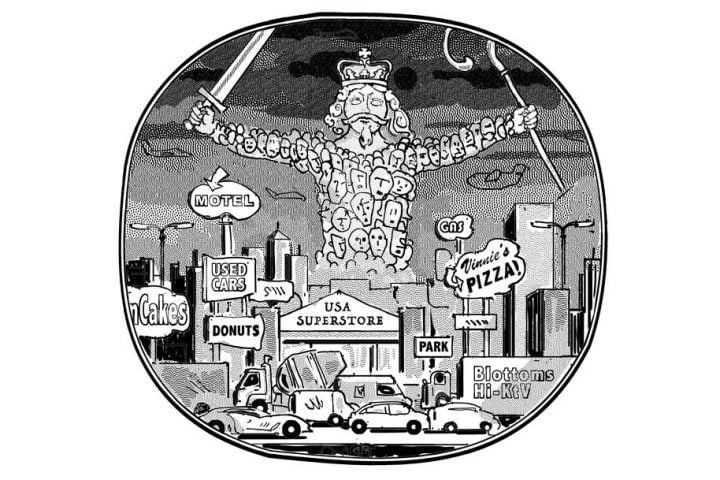

First, the diversity ideology tells us that what matters is not equal American citizenship, but the race, ethnicity, or gender into which one is born. Second, the diversity agenda pits so-called “marginalized” groups—ethnic, linguistic and social minorities, LGBT, immigrants, and women—against dominant groups: whites, males, and heterosexuals. Ironically, the diversity framework is not particularly diverse, multicultural, or “multi” anything. It is, instead, binary between two conflicting groups: the “oppressor” versus the “oppressed.”

Finally, the operationalization of “diversity” is in the hands of: unelected bureaucrats from the administrative state; partisan activist judges; and their ideological allies in America’s universities, corporations, churches, and media, driven by a mixture of ideology and careerism. Unlike the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, “diversity” is not a project that a majority of the American people ever embraced democratically.

As a political matter, mass immigration coupled with multicultural non-assimilation feeds the diversity machine and strengthens progressive liberalism. All this is apparently incomprehensible to the many conservatives who believe that the immigration debate is primarily about American employers’ perceived need for more cheap foreign labor.

Some of Salam’s policy recommendations are solid, others ambiguous. First and foremost, he argues that a point system like the ones used in Canada and Australia, which would rebalance immigration towards those with higher skills, should replace our current emphasis on bringing relatives—even remote ones—to the United States. He praises the excellent RAISE Act proposed by Tom Cotton and David Perdue (Republican senators from Arkansas and Georgia, respectively), which would base immigration on “points” gained by high employment skills, English fluency, and youthful high-wage potential. Salam also endorses mandatory E-Verify, the single most important method for employers to identify legal from illegal workers.

* * *

Salam favors a deal—amnesty for “unauthorized immigrants” (he never uses the term “illegal immigrants”) who have been in the U.S. for many years, accompanied by strict border enforcement. He supports amnesty for both civic reasons, holding out hope for assimilation, and the humanitarian one of reducing poverty. Once legalized, previously illegal immigrants would have full access to social safety net programs, thus alleviating poverty, particularly for their children.

He claims we have an “obligation” to pursue this course because we have “benefited from [their] labor.” On the contrary, many low-income Americans, our legal framework, and our democratic mores have not “benefited” from the lawlessness and crime that have too often accompanied mass illegal immigration. One has only to read Victor Davis Hanson’s reports from his home in California’s Central Valley to understand the havoc illegal immigration has wrought to the quality of life for the non-elite population of our country.

Moreover, Salam is murky about whether enforcement measures such as mandatory E-Verify would come before or after long-term illegal immigrants are granted legal status. He notes that combining a high-skilled immigration policy with reducing the number of immigrants is “defensible,” but he prefers focusing on rebalancing towards skills rather than embracing both options.

But both options are necessary. Cuts in legal immigration are as necessary today to achieve the patriotic assimilation of newcomers to our nation as they were when President Calvin Coolidge, for the same reasons, supported immigration reductions in 1924.

Those misgivings aside, Reihan Salam’s Melting Pot or Civil War? is essential reading for a thorough understanding of our immigration debate.