Books Reviewed

A review of Heloise & Abelard: A New Biography, by James Burge

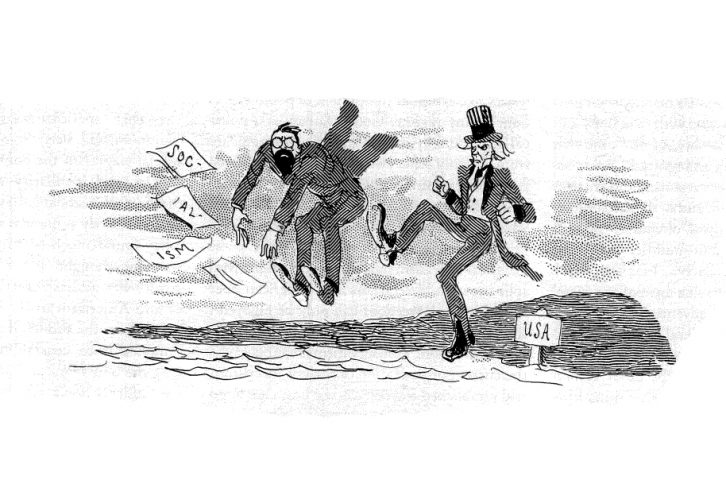

Fleshly love, philosophers have taught, coexists uneasily with love of truth. Arch-idealist Plato explicated this thesis most fully, but perhaps unique among philosophic theories, it has also found empirical confirmation in the lives of the philosophers themselves. Take a roll call of the great philosophers and you find that nearly all of them—Plato, St. Augustine, Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Kant, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, to name a few—were bachelors.

Yet the history of philosophy does furnish at least one great earthly love affair: Peter Abelard and Heloise. Abelard found in Heloise a woman whose dialectic talents equaled and quite possibly even surpassed his own. He discovered in a more than metaphorical sense that Truth, as Nietzsche once sardonically put it, is a woman. In Abelard and Heloise, mind and body could meet at last.

Popular imagination has raised Abelard and Heloise to the empyrean heights of Western literature's great lovers. Their names stand alongside Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra, Dante and Beatrice, and Dido and Aeneas as matchless examples of erotic love. No mere fabulist could produce a more fascinating and sometimes shocking union. Even philosophers—nay, especially philosophers—will find their story illuminating.

The plot goes like this: Abelard, having attained a reputation as a great logician and enfant terrible, arrives in Paris to claim the exalted post of master of the school of Notre Dame. The year is 1114, and Abelard is in his thirties. He boards with Fulbert, a church canon, who employs him to tutor his niece Heloise, a woman of fantastic learning and, we find out, appetite. When they're not discussing the Universals, the two are making love—or, for all we know, doing both at once.

Alas, for them the world of brute experience intrudes in the form of pregnancy. Abelard removes Heloise to his family in Brittany, and, to placate her uncle, agrees to marry her secretly. (Were news of the marriage to leak out, his career would be ruined.) Heloise vehemently opposes the marriage—their love should not bow to convention, and besides, "Who can concentrate on scripture and philosophy and be able to endure babies crying, nurses soothing them with lullabies, and all the noisy coming and going of men and women about the house?" Yet she consents.

When rumors of their marriage spread, Heloise denies them. An enraged Fulbert dispatches henchmen who seize Abelard at night and castrate him. (This is not a story for the faint of heart.)

Following this humiliation, Abelard convinces Heloise—again, she is opposed—that they should both enter religious orders. Heloise becomes a famous and celebrated abbess, though we know from her letters that she remained unapologetically loyal first to Abelard and the love they shared, and only second to God. Abelard becomes a monk but continues his philosophical pursuits. Ultimately, Rome condemns Abelard for heresy, and he throws himself on the limitless mercy of Peter the Venerable, abbot of the great monastic empire of Cluny.

* * *

And so the union of mind and body in this tale, unlike that of Ovid's Cupid and Psyche, ends in tragedy. Nonetheless, while it lasted, their lovemaking reached such heights as to become a fleshly representation of Plato's communion with the forms. To tell their story well requires deep literary gifts; happily, James Burge's engaging and sprightly new biography does them justice.

The Dutch historian Johan Huizinga warned in his famous study of the late Middle Ages that historians who rely on official documents rather than less reliable but more colorful personal chronicles fall into the "dangerous error" of forgetting "the fervent pathos of medieval life." Burge, a producer and director for the BBC and a columnist for The Independent, avoids this error by taking advantage of a newly-discovered trove of love letters which some scholars believe to be authored by Abelard and Heloise. The result is a personal and engaging tale, showing the two in high relief, and communicating to the reader the "fervent pathos" of their lives and times.

Until recently, scholars had only Abelard's philosophical treatises, his 20,000-word autobiographical "History of my Calamities," and a handful of letters between the lovers. But in 1999, after a decade of study, Australian scholar Constant Mews published translations of 113 new letters or parts of letters that he argued were authored by the two lovers. Not everyone agrees, and their authenticity will probably be disputed long into the future.

But that shouldn't stop us from having fun with them, and that is precisely what Burge does here. Exploring the human, intellectual, and political contours of this remarkable story, he draws on new and old sources and—perhaps too often, at least for my taste—his own speculation about what they and their fellows were thinking and feeling. (Burge goes overboard, for instance, when he attributes Fulbert's rage to his own sexual attraction to his niece. Isn't it enough that Abelard has deflowered Heloise and defiled Fulbert's house by carrying on a rather public love affair under his roof?)

Aside from that minor indulgence, however, Burge's account is enjoyable and enlightening. He savors the perennial modernism of these two lives, and obviously enjoys communicating it to the reader.

Abelard and Heloise inhabited a world that, like our own, was changing rapidly. They saw themselves and their times as modern. The 12th century, rather than a "middle" age between times of greater cultural achievement, was in fact a time of fantastic intellectual and cultural ferment.

"Abelard and Heloise saw the age in which they lived as almost bewilderingly modern," writes Burge, "a time when new ideas and new things were changing the world at a dizzying speed. They were at the beginning of something, not the middle." Indeed, there is no better proof of their awareness than the unusual name they chose for their son: Astralabe. The latest in scientific technology at the time, the astrolabe was used to follow the movements of the sun, moon, and stars. "They prided themselves on their rational understanding of the world," explains Burge. "Just as the astrolabe was a physical sign of the possibility of understanding through reason, the child was a physical expression of their love."

With so much possibility in the offing—only years after Abelard's death, the trickle of Greek scientific and philosophical texts into France on which he subsisted would grow to a veritable torrent—the authorities of the old order inevitably grew anxious. The sacred now faced serious competition from the profane, a rivalry that remains at the heart of the Western tradition.

Abelard didn't see the conflict in this way, however. Finding much truth in Greek philosophy, he civilized or Christianized it, arguing for instance that Plato was a proto-Christian. (The reader will recall that Dante placed the pagan philosophers Plato and Aristotle not in hell but in Limbo, the benign first circle.) Philosophy and religion share a common goal, he believed, and a religion that shied away from rational inquiry in favor of fideism was in danger of straying from Truth.

For this, and for treating the Scriptures and Church Fathers with the disinterested eye of the logician rather than the reverence of the believer (which he was), Abelard earned the enmity of some prominent Church leaders.

Many admirers idealize Abelard and Heloise's fearless flouting of convention. But surely the suffering they endured counsels a more modest moral to their story. Although we cannot know what befell them in the afterlife, they certainly didn't get away with their scandalous behavior—which included making love in a convent refectory—on this side of paradise. Heloise, it is true, was unrepentant to the end, but Abelard seems to have understood his "calamities" as just punishment for his sins.

Burge includes an appendix with excerpts from the newly-discovered letters. Tantalizing for all admirers of the two lovers, the letters belie the typical view of Latin as a dry and dead tongue. Observe the passion and sensitivity of these closing lines: The woman writes, "Vale, cor et corpus meum, et omnia dilectio mea" ("Farewell, my heart and body and my total love"); the man replies, "Vale dulcissima" ("Farewell, sweetest").

As 12th-century Christian philosophers go, Abelard hasn't fared too badly. Unlike Hugh of St. Victor and Roscelin, his name has not died, suggesting that if you go in for a school of philosophy that will be entirely ignored 900 years down the road, it's best to complement it with a steamy love life so that at least the literature departments will pay attention to you.

It's a good lesson, but one few philosophers will ever learn.