Books Reviewed

Kenyans appear to be very, very good at running long distances. In 1988, Kenya’s Ibrahim Hussein won the Boston Marathon, making him that competition’s first men’s champion from Africa. Kenyans have gone on to win 21 of the 31 races since Hussein’s breakthrough while also dominating the women’s competition, winning 12 of this century’s 20 races.

And it’s not just Boston. Kenyan men have finished first in 15 of the past 21 Berlin Marathons. Kenyans have also won seven of the 24 Olympic medals awarded in the men’s marathon since 1988, and five of those for the women’s marathon.

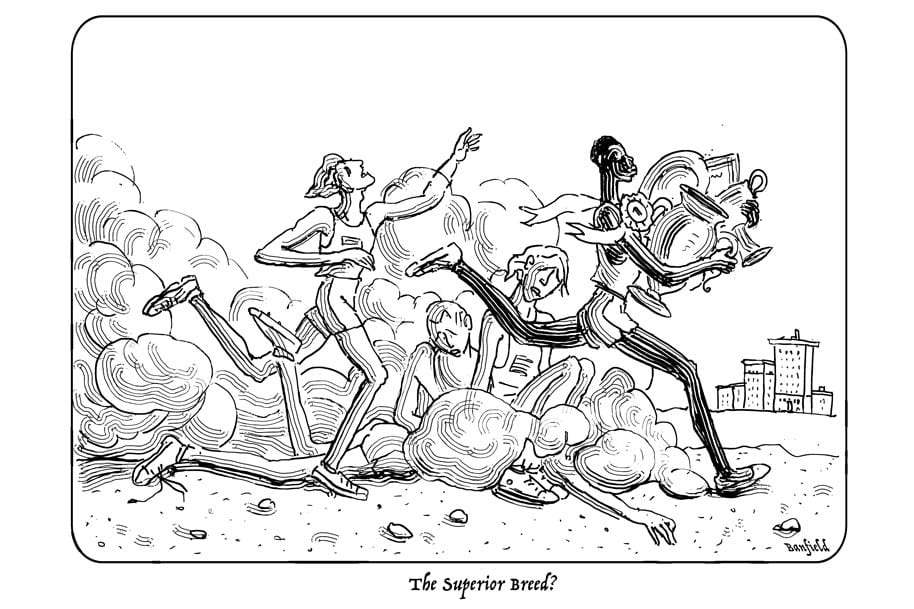

In other words, a country comprising two-thirds of 1% of the world’s population has come to dominate marathon racing in the 30 years since getting serious about international competition. Nor is this talent confined to a handful of exceptional athletes. Ambrose “Amby” Burfoot, an American who won the 1968 Boston Marathon, wrote in Runner’s World in 1992 about Bengt Saltin, a Swedish physiologist who traveled to Kenya with “a half-dozen national-class Swedish runners.” Saltin held competitions in the Rift Valley, home of the Kalenjin tribe that produces most of Kenya’s best runners despite accounting for less than one eighth of its population. The results saw “the Swedish 800-meter to 10,000-meter specialists…soundly beaten by hundreds of 15- to 17-year-old Kenyan boys.”

For Burfoot and Saltin, Kenyan supremacy in long-distance running represents the “perfect combination of genetic endowment with environmental and cultural influences.” Kalenjin culture emphasizes stoicism and aggression, Burfoot writes, qualities that help runners train and compete. The Kalenjin inhabit a part of Kenya more than a mile above sea level. This thin atmosphere develops the body’s ability to use oxygen efficiently, an enormous advantage when running distances.

But, Burfoot points out, the Himalayas and Andes are also elevated, yet Tibetans and Peruvians don’t dominate marathon races. Part of the Kalenjin advantage appears to be innate. In The Sports Gene (2013), David Epstein accounts for this advantage in terms of body structure. Scientists’ examinations have shown that, as a group, the Kalenjin have unusually long, slender legs. The pendulum effect of running with thick calves and ankles is particularly disadvantageous over long distances. By contrast, the “running economy” enjoyed by those with slim lower legs is optimal for taking faster, longer strides than other runners do when using the same amount of oxygen.

Saltin’s research, as summarized by Burfoot, showed these same forces operating at the cellular level as well. Compared to Swedish runners, for example, Kenyans’ quadriceps had “more blood-carrying capillaries surrounding the muscle fibers and more mitochondria within the fibers (the mitochondria are the energy-producing ‘engine’ of the muscle).” These attributes gave the Kenyan runners Saltin tested the ability to burn oxygen with “incredible efficiency,” along with “high fatigue resistance.”

Knowing all this, we can only be puzzled by one reviewer’s judgment that Skin Deep: Journeys in the Divisive Science of Race “demolishes the idea of genetic explanations for any region’s sporting achievements.” The review scoffs: “Some have speculated that Kenyans might have, on average, longer, thinner legs than other people, or differences in heart and muscle function.” To the contrary, Skin Deep’s author Gavin Evans shows that “Such claims for athletic prowess are lazy biological essentialism, heavily doped with racism.”

The review, which appeared in the July 2019 issue of Nature magazine, was written by Angela Saini, author of another recent book on the same subject: Superior: The Return of Race Science. Both writers are journalists based in England. Saini’s enthusiastic review reflects the belief that Skin Deep buttresses her book’s thesis, which is that there are no important biological differences among sub-groups of the human race, however defined, and that those who think such differences do or might exist are either saps or bigots.

Strangely, Saini’s brief book review makes her purposes clearer than they become at any point in the pages of Superior. “Racist ‘science’ [is just] a way of rationalizing long-standing prejudices, to prop up a particular vision of society as racists would like it to be,” she writes in Nature. “Racists don’t care if their data are weak and theories shoddy. They need only the thinnest veneer of scientific respectability to convince the unwitting.” A world “in thrall to far-right politics and ethnic nationalism demands vigilance,” the sort of vigilance animated by books like Skin Deep (and, implicitly, Superior), which can help the public “become less susceptible to manipulation by hardened racists with political agendas.” Therefore, “We must guard science against abuse and reinforce the essential unity of the human species.”

Unfortunately, the “essential unity of the human species,” noble concept though it may be, is a cosmic or moral axiom rather than a scientific principle. Guarding science against abuse begins with making empirical observations accurately and reporting them scrupulously, even when the data cast doubt on our most cherished beliefs and aspirations. No intellectually honest writer would say, “Some have speculated that Kenyans might have, on average, longer, thinner legs than other people,” any more than she would say, “Some have speculated that Pygmies might be, on average, shorter than other people.” These are verifiable facts, not tendentious conjecture.

Inconvenient Truths

It’s a fair indication of Saini’s reliability that she cannot even be trusted to summarize an ally accurately. Evans’s “demolition” of the proposition that innate differences play a role in Kenyans’ running success is, in fact, a grudging acknowledgment that the idea is almost certainly true, so that the only remaining question concerns the importance of inherited biological factors relative to other causes. For example, Skin Deep offers one scientist’s opinion that we can “say with reasonable confidence that social and economic factors are the primary factors driving the success of Kenyan distance running” (emphasis added). Evans subsequently stipulates that his argument “doesn’t imply that genetics plays no role at the population level.”

Slow-twitch muscle fibres, longer legs and lighter bones provide a significant advantage, and these are in higher supply in Kenya, Ethiopia and Morocco than in, say, Samoa, Nigeria and Jamaica. And when these long legs and light bones combine with high altitude and a running-to-school lifestyle, potential kicks in.

For most of the millennia during which homo sapiens have existed as a distinct species, inheritable capacities related to physical strength and endurance were crucial to whether individuals survived and social groups flourished. But over recent centuries, humans’ cognitive abilities have grown more important, relative to physical ones, for individual and group success. Accordingly, Skin Deep and Superior are concerned with thinking, not running. Both books’ overriding purpose is to discredit and denounce all suggestions that heritable cognitive abilities and psychological dispositions are distributed across the human race in any way other than evenly or randomly.

In Skin Deep, Evans pivots from one chapter on athletic ability, which judges it to be somewhat heritable, to nine chapters on intellectual ability. In them, he argues that intelligence is much harder to define and measure than physical ability, and that no evidence has yet emerged proving the existence of significant innate cognitive differences among racial or ethnic groups. Ultimately, while conceding that such evidence may yet be discovered, Evans aligns himself with what he considers the “clear majority of geneticists and other scientists” who believe “that the evolutionary factors acting against population differences in cognition are far stronger than those favouring them.”

As shown by her review’s misrepresentation of Skin Deep’s argument, Saini is more reluctant than Evans to acknowledge any inherited differences among population groups. If there really are some genetically transmitted differences among ethnic or regional subsets of the human race, then there might be others. Her response is to deny everything rather than concede anything. But when this strategy culminates in ascribing awareness of Kenyans’ running prowess to “lazy biological essentialism,” Saini inadvertently affirms one of Superior’s targets, blogger Steve Sailer, who says that the definition of racism has expanded to include the “high crime of Noticing Things.”

Like all books with a clear agenda, Superior works to convince readers that the author’s point of view is correct. The book’s most interesting, awkward, and melodramatic passages, however, find Saini struggling to convince herself. In the book, unlike in her review of Skin Deep, she yields some ground, acknowledging that there are “superficial” biological differences among population groups. Superior offers examples—skin color, and susceptibility or imperviousness to certain diseases—but never defines what makes a trait superficial, or what differentiates traits in that category from significant ones.

Yet even this modest, vague concession ends up distressing Saini. She notes that the Bajau people of Southeast Asia have “evolved an extraordinary ability to hold their breath underwater for long periods of time” after centuries of diving to hunt fish. The Bajaus’ unusually large spleens, which help sustain the blood’s oxygen levels, appear to be “a measurable genetic difference between them and others, sharpened over many generations by living in an unusual environment.”

That thought occasions an interior monologue, raising “a question we don’t like to ask out loud.” Is it possible, she wonders, “for a group of people, isolated enough by time, space, or culture, to adapt to their particular environment or circumstances in different ways? That they could evolve certain characteristics or abilities, that they might differ in their innate capacities?” Seeking reassurance, Saini interviews “India’s leading population geneticist,” Kumarasamy Thangaraj. “‘Could there be psychological differences between population groups?’ I asked Thangaraj, tentatively. I go further. ‘Differences in cognitive abilities?’” The scientist does not allay her fears. “‘That kind of thing is not known yet,’ he replied. ‘But I’m sure that everything has [a] genetic basis.’”

She is even more distressed by her interview with another prominent geneticist, Harvard Medical School’s David Reich. “I know that Reich is not a racist,” she writes, which only makes it harder for her to believe what he tells her: after 70,000 years apart from one another, adapting to very different environments, Europeans and Africans may turn out to have (in Saini’s summary of Reich’s views) “more than superficial average differences,…possibly even cognitive and psychological ones.” Such thoughts, she writes, are ones “I never expected to hear from a respected mainstream geneticist.”

Saini, like Evans, has to account for Reich due to his widely discussed book, written for laymen, Who We Are and How We Got Here (2018). What she lauds as the essential unity of the human species, Reich describes as “an orthodoxy that the biological differences among human populations are so modest that they should in practice be ignored.” This consensus, forged by 20th-century anthropologists and geneticists, came to regard race as a pernicious concept, integral to eugenics and Nazism, but also a meaningless one. No one, that is, could identify the boundaries between racial groups, and scientists asserted with increasing confidence that the genetic variation within any given group was much greater than the variation between groups. It is common in these circles to eschew the term “race” altogether in favor of the more clinical “population group.”

Saini follows this convention, but worries that it won’t suffice. Even scientists who used the right language about population groups, and were clearly anti-racist, continued to pursue research that was “all about finding out how people differed.” Better that they should have treated the question as settled and closed: “the genetic variation between us was already known to be trivial.” Better still that they should have realized it was essential to “reinforce that we were all the same underneath.” Responsible scientists, aware of the history of racist thought and the existence of racist publicists who will seize any scrap of evidence to validate their malign project, will and must “resist the urge to group people at all.”

Sacrilege and Censorship

Gavin Evans trusts, basically, that honest, competent scientific investigation will vindicate the unity of the human species. Saini, less sanguine, can’t decide whether race science is intellectually bad or morally bad. If the former, its weak evidence and arguments will discredit its conclusions, which means race science is deplorable but ultimately too absurd to be a problem. But at some points in Superior, she’s less convinced that wisdom and decency are destined to triumph, and leans toward the position that scientists must simply stop asking questions whose answers might give comfort to racists opposing an ever more equal, inclusive world.

For Reich, the fact that such anti-intellectualism is well-intentioned—he, too, opposes what he calls “hateful ideas and old racist canards”—makes it more dangerous, not less. As an intellectual matter, Who We Are declares that the “indefensibility” of the orthodoxy about a genetically undifferentiated human race is becoming “obvious at almost every turn.” As scientists use the latest tools of genetic analysis more extensively, it becomes harder to “deny the existence of substantial average genetic differences across populations” or to assume that these differences cannot extend to “cognitive and behavioral traits.”

As a political matter, the “well-meaning people who deny the possibility of substantial biological differences among human populations are digging themselves into an indefensible position.” Scientists somewhere in the world will use the latest tools to pursue questions about group differences, however strongly defenders of the crumbling orthodoxy may object. When the answers further undermine that orthodoxy, supporters of racist canards will claim vindication—both as having been right, and as having been the only participants in the debate who honored the scientific imperative to follow the evidence where it leads.

Some who oppose scientific investigation of differences among population groups are not content to denounce; they want to suppress. Who We Are cites Northwestern University political scientist Jacqueline Stevens, who has called on the federal government’s National Institutes of Health to, in her words:

issue a regulation prohibiting its staff or grantees…from publishing in any form—including internal documents or citations to other studies—claims about genetics associated with variables of race, ethnicity, nationality, or any other category of population that is observed or imagined as heritable unless statistically significant disparities between groups exist and description of these will yield clear benefits for public health, as deemed by a standing committee to which these claims must be submitted and authorized.

If translated from bureaucratese into Latin, Stevens’s proposal would pair nicely with the Inquisition’s condemnation of Galileo for heresy.

Nor is she alone in opposing open inquiry. Linguist Noam Chomsky (of course) argued in Language and Problems of Knowledge (1987) that while “people differ in their biologically determined qualities…discovery of a correlation between some of these qualities is of no scientific interest and of no social significance, except to racists, sexists and the like.” Thus, investigating group differences is pointless and harmful, since it assumes that “the answer to the question makes a difference,” which it does not—except, again, “to racists, sexists and the like.”

Journalist John Horgan wrote in a 2013 article for Scientific American that research universities’ institutional review boards, which must approve projects involving human subjects, “should reject proposed research that will promote racial theories of intelligence, because the harm of such research—which fosters racism even if not motivated by racism—far outweighs any alleged benefits.” Horgan is enthused about research that discredits such theories, however. The only way to satisfy both imperatives would be for review boards to approve only those research projects that support the anti-racist cause, as he understands it, or for them to retroactively disapprove projects, and prevent the publication of their findings, if the results end up being inimical to that cause.

Saini herself favors impeding the spread of harmful rhetoric and research through pressure on big internet firms. In 2019 she wrote, also in Scientific American, that because “racists exist at all levels of society, including in academia, science, media and politics,” the public must “recognize hatred dressed up as scholarship and learn how to marginalize it, and be assiduous in squeezing out pseudoscience from public debate.” She hastens to reassure that this obvious free speech issue “is not a free speech issue; it’s about improving the quality and accuracy of information that people see online, and thereby creating a fairer, kinder society.”

Keeping Our Heads

The anti-racist project’s epistemological rules are impossible to formulate in a way that renders them either coherent or benign. That the truth will set you free is a precept shared by the Gospel and the Enlightenment. But it’s a perverse distortion to conclude that any finding about how the world works that doesn’t set you free, that complicates or fails to advance your preferred political cause, is not and cannot be true.

By the same token, the standard that Proposition X must be false if Bad People endorse it is no way to run a laboratory. James Watson, a founder of modern genetics as co-discoverer of DNA’s role in transmitting biological information, has become a pariah in his old age (he’s 91) by blurting out views on group differences in abrasive ways. His greatest-hits album, compiled on the blog of computational biologist Lior Pachter, is distressingly robust. Watson accommodates modern sensibilities solely by virtue of being an equal-opportunity offender: “Whenever you interview fat people, you feel bad, because you know you’re not going to hire them.” “[The] historic curse of the Irish…is not alcohol, it’s not stupidity…it’s ignorance.” “Anyone who would hire an ecologist is out of his mind.”

Insult-comic persona aside, when edited by himself or others, Watson poses questions that should provoke thought, not anger. “There is no firm reason to anticipate that the intellectual capacities of peoples geographically separated in their evolution should prove to have evolved identically,” Watson wrote in his memoir, Avoid Boring People (2007). “Our wanting to reserve equal powers of reason as some universal heritage of humanity will not be enough to make it so.”

Though in a 2019 article for Stat, science journalist Sharon Begley lists this contention as just another of Watson’s “odious” views, a strident adjective is not a refutation. Nor does it dispatch Watson’s null hypothesis. “Writing now,” Reich says in Who We Are, “I shudder to think of Watson…behind my shoulder,” a prudent concern in light of how the older man’s career and reputation have crashed. Yet if there is a firm reason to think geographically isolated population groups have evolved identically, either by chance or necessity, Who We Are supplies nothing that reveals it and good reasons to doubt it.

In light of these considerations, we can make two observations about the “indefensible position,” as Reich calls it, being taken by those “who deny the possibility of substantial biological differences among human populations.” First, people who think they’re winning a debate rarely try to shut it down or keep it secret. Reich opposes the anti-racists’ anti-science defeatism, in part, on the grounds that it’s too early to assume that most, or any, of geneticists’ discoveries will prove inimical to the political hopes he shares with Saini and Evans.

In any case, it is clear that the question of whether population groups have inherited differences in cognitive ability would be hard to answer even if it were not politically incendiary. For one thing, to isolate inter-group differences based in biology from those caused by culture and circumstance is a formidable challenge. Furthermore, intelligence is harder to define, measure, and compare than, say, the ability to run 26.2 miles. Evans goes so far as to suggest that we stop using the word “intelligence” altogether, an innovative but not totally surprising way to criminalize noticing.

Second, even if anti-racists’ fears about future biological findings are realized, it’s an unforced error to catastrophize this prospect. “The logical consequence of insisting that IQ gaps between races are biologically determined is that nothing in human society can really be changed,” Saini writes, absurdly. An egalitarianism so frail that it can be shattered by persuasive evidence that population groups have inherited differences in socially consequential attributes is deeply flawed. It stood in need of revision long before scientists began examining group differences. As psychology professor Steven Pinker pointed out in The Blank Slate (2002), population groups’ essential similarity “is a factual question that could turn out one way or the other.” The mistake is to think that the discovery of significant dissimilarities would justify a caste system, as the most fanatical racists believe, or would render castes irresistible or immovable, as the most fanatical anti-racists think.

Egalitarianism Without Absurdism

We should make our theories—political and moral, as well as scientific—fit the facts, not demand that the facts fit our theories. People are equal in some ways and unequal in others, which means that any egalitarianism that we can both admire and implement will give sameness and difference the respect each deserves. Suppose that between two individuals, X is more intelligent (or musical, athletic, physically attractive, etc.) than Y. Suppose, further, that this inequality cannot be wholly explained by environmental differences such as upbringing or education, and might be reduced but cannot be eliminated by equalizing such factors.

Nothing in this scenario supports the conclusion that X and Y should be other than civic and moral equals. In a well-governed republic they will obey the same laws, enjoy the same rights, and shoulder the same obligations. As Thomas Jefferson wrote near the conclusion of his presidency, “Because Sir Isaac Newton was superior to others in understanding, he was not therefore lord of the person or property of others.” In a successful society animated by the republican spirit, X and Y will join fellow citizens who honor and encourage one another, each concerned that all others fulfill their potential. In his 1992 speech to the Republican National Convention, Ronald Reagan said, “[W]e are all equal in the eyes of God. But as Americans that is not enough; we must be equal in the eyes of each other.” Egalitarianism rightly understood does not object, however, if X but not Y becomes a geneticist (or a pianist, shortstop, or fashion model), provided that Y’s lesser talents were still given a fair opportunity to manifest themselves.

Suppose, similarly, that members of Group A turn out to be more likely than those in Group B to possess some socially consequential aptitude. Inquiries into the cause of the disparity make it increasingly clear that the origins are, to some significant extent, innate rather than environmental. Civic and social egalitarianism still demands that all members of A and B enjoy equal rights and respect, but also accepts that different proportions of A and B will end up as geneticists, shortstops, etc. “The right way to deal with the inevitable discovery of substantial differences across populations,” Reich counsels, is to accord “everyone equal rights despite differences that exist among individuals.” The important thing is to “celebrate every person and every population as an extraordinary realization of our human genius and to give each person every chance to succeed, regardless of the particular average combination of genetic propensities he or she happens to display.”

I once wrote a book that asked what it would mean for a nation’s welfare state to be a completed endeavor, to acquire all the resources and authority it could possibly use to achieve its objectives. The answer turned out to be that there is no answer, that the welfare state’s ultimate purpose is to facilitate (and necessitate) the welfare state’s perpetual expansion.

Now that identity politics has come to be the salient feature of modern American liberalism, it’s time to update my older question. What, exactly, are 21st-century identitarians trying to accomplish? What would it mean to achieve the equality they are demanding, and how will we know they’ve succeeded?

As with the welfare state, the goal’s only definable feature is that it recedes constantly. Ending racism requires “more equitable education and healthcare,” Saini writes, and a commitment “to end discrimination in work and institutions, to be a little more open with our hearts and maybe also with our borders.” But how much more would be enough more? Everything about the theory, practice, and spirit of modern egalitarianism tells us that Saini’s “little more” is going to end up being a great deal more, and for a very long time.

Along the same lines, what does ending discrimination consist of? Not the elimination of all disparities, we’ll be told, just the bad ones, the unfair ones. In practice, this means that any particular disparity is presumed guilty until proven innocent of resulting from discrimination, defined expansively to encompass such unspecifiable concepts as unconscious, implicit, and structural bias. Since, for example, racism informs the lazy biological essentialism that ascribes innate running ability to Kenyans, we cannot declare victory against discrimination until that golden day when Kenyans and Samoans are proportionally represented among marathon winners.

To spell out the implications of Saini’s anti-racism is to demonstrate that it’s as ominous as it is ludicrous—an egalitarianism that strangles liberty, fraternity, and fairness. The saner, safer path is the one laid out by David Reich: “If we aspire to treat all individuals with respect regardless of the extraordinary differences that exist among individuals within a population, it should not be so much more of an effort to accommodate the smaller but still significant average differences across populations.”