“If an American president loses more Americans over the course of six weeks than died in the entirety of the Vietnam War, does he deserve to be reelected?” Olivia Nuzzi, a New York magazine writer, put this question to President Trump in late April. She was referring, of course, to deaths resulting from COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus that began to infect and afflict humans in late 2019, triggering a global pandemic in 2020.

The president answered that while even one death is too many, his administration has “made a lot of really good decisions,” which rendered the virus less widespread and lethal than the most dire projections had foreseen. Though not directly engaging Nuzzi’s question about reelection, his implication was clear: he and his appointees had responded to a sudden, severe public health crisis as well as any reasonable person could expect. If a giant meteor were to strike midtown Manhattan, only the most partisan hack would assert that the incumbent president had, through unspecified errors of omission and commission, “lost” thousands of Americans in a single day.

A key factor determining the outcome of this year’s presidential election will be whether voters use Nuzzi’s or Trump’s framework to comprehend the coronavirus pandemic. The president’s challenge is daunting. The number of U.S. deaths officially attributed to COVID has now risen beyond 140,000, beyond the total of American lives lost in all U.S. military actions since the end of World War II: Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, Afghanistan, Iraq, plus a score of smaller engagements. At the same time, millions of Americans—through some combination of government decree and personal preference—stayed home from work, school, and shopping to avoid catching and spreading the virus. As a result, the nation’s unemployment rate soared from 3.5% in February to 14.7% in April, the highest level since the 1930s.

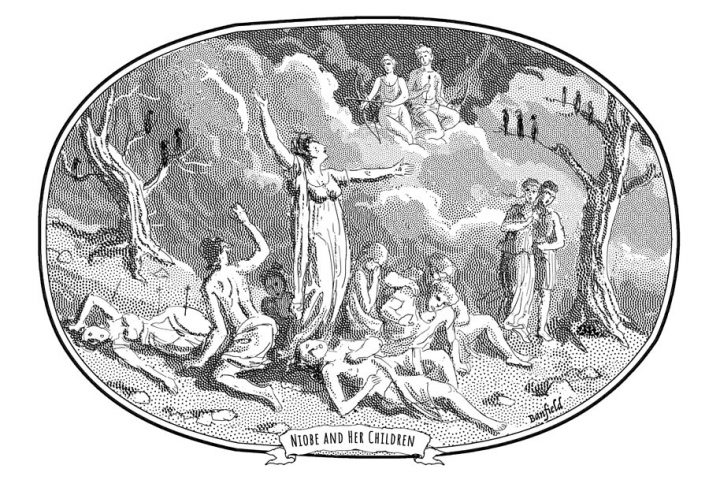

For Trump, Plan A had been to seek reelection as the candidate of peace and prosperity. Widespread disease and economic privation will now require a Plan B, but its particulars and prospects are unclear. The epidemic has been a jarring demonstration that despite modern medicine’s triumphs, we are physiologically similar to the humans who succumbed to devastating plagues centuries ago. Republicans fear, and Democrats hope, that we are also psychologically similar to our remote ancestors who occasionally sacrificed a king in hope the gods would end a series of bad harvests.

We won’t know until November how voters will judge Trump and the coronavirus pandemic. In the meantime, it is useful to explore a separate question: how should they assess our government’s response to this emergency? Three sudden, shocking crises in two decades—9/11, the Great Recession, and COVID-19—indicate that black swans glide by more frequently than formerly supposed. If we are to be increasingly reliant on government’s ability to anticipate and react to such challenges, we need to consider how our system acquits itself. In other words, what is the baseline by which the response of an administration to the pandemic of 2020 should be judged? What constitutes a passing grade?

This would be a hard question in any case, but is especially so in an election that will be, above all, a referendum on this particular president. As you may have heard, Donald Trump rubs some people the wrong way. (When they complain, he rubs harder.) Political discord would have been increasing at this point in the electoral cycle even without a public health crisis. With it, the president’s antagonists have been especially strident in accusing him of lethal ineptitude. Trump will get worse as the pandemic does, writes New York’s Andrew Sullivan. “I used to be disgusted by him. I am now incandescent with rage at him and the cult that enables his abuse of all of us.” Similarly, the Atlantic’s George Packer charges that the coronavirus revealed America to be a “failed state,” a country with “shoddy infrastructure and a dysfunctional government whose leaders were too corrupt or stupid to head off mass suffering.” While his administration “squandered two irretrievable months to prepare,” President Trump offered only “willful blindness, scapegoating, boasts, and lies.”

Even apart from such furious critics, the default answer to the question of how the government should have responded to this public health crisis remains injurious to Trump’s cause. We tend to judge an actual government’s actual performance by imagining “an omnicompetent government authority,” in the words of Christopher DeMuth, that “could have nipped the crisis in the bud.” Pretending that this governance fantasy camp is applicable to the real world, he argues, “elides the profound problems of uncertainty and conflicting information and interpretation that precede every catastrophe.”

Knowing

An omnicompetent government would effortlessly surmount three kinds of problems that beset real officials. First, as DeMuth indicates, it’s hard to know things, to determine what’s true and what’s important in the midst of a crisis. Carl von Clausewitz described war as the province of uncertainty and chance, where the combatant “constantly finds things different from his expectations.” Those who must contend with other sudden, encompassing emergencies face the same quandary: facts are fragmentary, disputed, unreliable, contradictory…and crucial.

An epidemic’s distinctive informational problems are especially severe. Even when we have good reason to know a fact, we may well struggle to believe it. “Normalcy bias” strongly disposes us to think that what we’ve grown accustomed to in the past is the best guide to what we’ll encounter in the future. As a result, “Anything you say in advance of a pandemic seems alarmist,” according to Michael Leavitt, secretary of Health and Human Services from 2005 to 2009. But it is often the case that anything you do “after it starts is inadequate.” The challenge posed by SARS-CoV-2 has been especially difficult to gauge. Science magazine reported in April that the newly discovered virus “acts like no pathogen humanity has ever seen.”

President Trump said several things about SARS-CoV-2 that his enemies cherish and his advisors regret. These include claims in February 2020 that the virus would weaken in the warmer weather of April or, more generally, “One day it’s like a miracle—it will disappear.” But he was hardly alone in underestimating the virus’s danger. In January Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and also the Trump Administration’s most prominent medical expert, spoke more guardedly than Trump, but still indicated that the danger was modest and manageable. This “is not a major threat to the people of the United States,” he told one interviewer, and “not something that the citizens of the United States right now should be worried about.” He said to another, “It’s a very, very low risk to the United States, but it’s something we, as public health officials, need to take very seriously.” Subsequently, the government moved over the course of five weeks from saying that it served no purpose for people (other than those working in the medical profession) to wear face masks, to recommending such masks for anyone spending time in a public place. Fauci recently admitted that the initial advice against masks was deliberate disinformation: officials worried about limited quantities of protective equipment did not want civilians acquiring so many masks that doctors and nurses would be forced to work without them.

Vox, the self-designated online source of explanatory journalism, tweeted on January 31, “Is this going to be a deadly pandemic? No.” On March 24 it deleted the tweet with an oblique formulation that admitted no error: the older tweet “no longer reflects the current reality of the coronavirus story.” Similarly, the New York Times ran an article in April strongly implying that a 74-year-old man died of COVID-19 because he took a trip abroad after Fox News coverage convinced him that the coronavirus was not particularly dangerous. It was later discovered that the Times reporter who wrote the story had tweeted on February 27, “I fundamentally don’t understand the panic: incidence of the disease is declining in China. Virus is not deadly in vast majority of cases.”

Those who now appear to have been complacent about COVID-19 go beyond public officials and writers spouting off. The S&P 500 stood at 3,386 on February 19, 2020, the best close in its history. In other words, the consensus in the fiercely competitive investment field, where people make fortunes if their predictions are correct and lose them if their predictions are wrong, was that economic prospects had never been better.

Yet by February 20, China had already recorded 2,118 deaths from COVID-19. Wuhan, the city of 11 million people where the disease originated, had been locked down, and there were cases reported in 26 other countries—throughout Asia, in Europe, Canada, and the U.S. Eleven people outside China had died of it. Media coverage of the virus’s spread had been exhaustive; no one on Wall Street can claim that they were taken by surprise. As the pandemic worsened, the S&P 500 fell to 2,237 on March 23, a decline of 33.9%. The exceedingly thoughtful Slate Star Codex blog reviewed the scorecard of our “best predictive institutions” and concluded that “predicting the scale of coronavirus in mid-February—the time when we could have done something about it—was really hard.”

The fundamental explanation for this kind of error, in the words of Paul Slovic, a psychologist who studies how humans comprehend and respond to risk, is that “[o]ur feelings don’t do arithmetic very well.” We do especially badly, he says, when the equation involves events that are highly unlikely but terribly consequential if they do occur. Either we under-react by treating a very small probability as a virtual impossibility, or we over-react by treating it as the apocalypse. Over the course of five weeks in February and March, Wall Street gave both wrong answers.

Choosing

The second problem confronting real governments, as opposed to imaginary omnicompetent ones, is that it’s hard for the officials who formulate and implement the response to a sudden crisis to choose things. In part, it’s hard to choose because it’s hard to compare: costs and benefits, risks and rewards, short-term and long-term outcomes. These high-stakes tradeoffs demand hard choices but invite easy moralizing. In a hearing on workplace protections against coronavirus transmission, Ohio’s Democratic senator Sherrod Brown demanded that Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin specify “how many workers should give their lives to increase our GDP by half a percent” or raise the “Dow Jones by a thousand points.” Similarly, the Atlantic’s Amanda Mull denounced Georgia’s decision to be one of the first states to lift its quarantine restrictions, calling it an “experiment in human sacrifice” that will determine “just how many individuals need to lose their job or their life for a state to work through a plague.”

Such imbecilic stridency is much older than the coronavirus pandemic. In 1995, for example, the federal government restored states’ ability to set highway speed limits above 55 miles per hour, the maximum imposed during the 1973-74 oil shortage. Citing a Department of Transportation study that predicted 6,400 additional driving fatalities per year as the result of the increased speed limits, Ralph Nader condemned legislators for passing, and President Clinton for signing, the bill: “History will never forgive him and his allies in Congress for this assault on the sanctity of human life.” In fact, motor vehicle fatalities declined after the law was changed. By 2018 they were 12.6% lower than in 1995, despite the U.S. population being 24.5% larger.

More importantly, Nader’s argument has emotional but not logical force. If the sanctity of human life were the sole consideration, we would mandate a nationwide speed limit of 20 miles per hour. Sensibly, America declined to convene a board of philosophers to ponder the morally optimal mix of highway speed and safety. Instead, a free, democratic people arrived at a rough-and-ready solution: the 55-mile-per-hour limit was widely disliked and disobeyed. After millions of people had voted against it with their accelerator pedals, Congress voted against it formally. There’s no record of any senator or representative losing an election or even facing political static for voting to legalize faster driving.

By the time Congress settled the question, the highway speed limit debate had rehashed the same arguments for two decades. Governance requiring trade-offs is more difficult in “the fog of war,” the uncertainty and confusion that descend on policymakers in a sudden crisis. The choices become harder because the range of possible results becomes wider. On May 12, 2020, Dr. Fauci warned Congress that “suffering and death” would result if states ended their quarantine policies prematurely. Ten days later, he told an interviewer that maintaining the stay-at-home orders for too long could end up causing “irreparable damage,” social and economic, presumably, rather than strictly medical. The statements pull in different directions, but there’s no reason both can’t be true. It’s bad for the government to do too little, too late…but also to do too much, either too soon or for too long. If there’s a sweet spot between these errors, it is especially hard to locate when the relevant information is scarce and dubious.

We can see how such choices are harrowing during an emergency, when they have to be made, by considering that they can remain contested many years later, long after hindsight is supposed to have rendered everything clear. In 1999, the world was apprehensive about “Y2K,” the prospect of unleashed chaos when computers freaked out trying to decide whether 01/01/00 designated the first day of 1900 or of 2000. “The Y2K Nightmare,” Vanity Fair warned, would reveal that “folly, greed and denial” had “muffled two decades of warnings from technology experts” about a “ticking global time bomb.” But January 1, 2000 came and went without power plants shutting down, bank balances vaporizing, or food supply-chains disintegrating. Either the bomb was a dud or it had been defused. We still don’t know which.

It is especially difficult for officials in a democracy, who necessarily think about the next election, to compare and choose. The incentives they face prohibit them from responding to a prospective crisis in the same way a life-tenured philosopher-king would. The latter’s far-sighted belief that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure doesn’t do the former much good. A democratic politician, no matter how responsible and well-intentioned, confronts a dilemma: the better you are at preventing some disaster, the more likely it is voters will conclude you overreacted to a non-event. The preventive measures’ costs and burdens are tangible, but the benefits of a disaster that did not occur—either because it really was prevented or because it never actually needed to be prevented—are conjectural. The elected official who makes risk-averse investments in preventive measures has the satisfaction of building robust protective systems that will make his successors’ lives easier, among the weakest inducements in politics.

Doing

The third problem facing governments that are not omnicompetent, a problem especially acute during a sudden crisis, is that even after you’ve learned as much as you can about the emergency and made the best choices the circumstance allows, it’s hard to do things. More precisely, it’s not that hard to do things in the sense of issuing orders, taking actions, or bustling about looking busy and concerned. It’s hard, rather, to get things done, to implement policies and accomplish intended results.

We fall naturally into speaking of the government as “a unitary, rational decisionmaker: centrally controlled, completely informed, and value maximizing,” Graham T. Allison wrote in his classic Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (1971). But generally, he reminds us, it is more accurate to view government as “a conglomerate of semi-feudal, loosely allied organizations, each with a substantial life of its own.” Elected leaders “sit…on top of this conglomerate,” but government’s actions happen “less as deliberate choices and more as outputs of large organizations functioning according to standard patterns of behavior” (emphasis in the original).

Each entity, Allison says, “acts in quasi-independence,” even though “few important issues fall exclusively” inside any particular one’s domain. As a result, “the” government response to any challenge “reflects the independent output of several organizations, partially coordinated by government leaders,” who can “substantially disturb, but not substantially control, the behavior of these organizations.” Harry Truman made the same point less clinically: “I sit here all day trying to persuade people to do the things they ought to have sense enough to do without my persuading them.” Such pleading, he lamented, is “all the powers of the president amount to.”

So, for example, the Communicable Disease Center, founded in 1946, acquired its current name, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 1992. (Its acronym has been CDC throughout.) A typical citizen contemplating a federal agency with 11,000 employees, a budget of $12 billion, and called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, might reasonably expect this to be the governmental body that…controls and prevents diseases. When 140,000 Americans die from a virus over a few months, that citizen is unlikely to applaud CDC for a mission accomplished.

That judgment may be correct, but needs to be qualified by understanding the situation’s complexity. However vigorously one might argue that CDC should have sole, primary, or even clear responsibility for preventing or mitigating an epidemic, the reality is that it does not. A different law, the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act of 2006, created a new HHS entity distinct from CDC: the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Response and Preparedness (ASPR). Its job, according to the most recent version of the law, is to “[p]rovide integrated policy coordination and strategic direction, before, during, and following public health emergencies, with respect to all matters related to Federal public health and medical preparedness.” In March Politico described CDC and ASPR as “two agencies that have spent years battling over which gets to be in charge of the nation’s emergency medical stockpile.” Meanwhile, according to yet another law, the Surgeon General has the authority to “make and enforce such regulations as in his judgment are necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases.”

CDC, ASPR, and the Surgeon General are all housed within the Department of Health and Human Services, alongside other bodies that play a role in responding to a contagion, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The HHS secretary has “statutory responsibility for preventing the introduction, transmission, and spread of communicable diseases in the United States,” according to CDC’s website. But it is not clear if this authority supersedes the statutory responsibility elsewhere given to ASPR and the Surgeon General, or if it requires the HHS secretary to respect those entities’ congressionally designated missions and capacities by weaving their work into a larger government response. In any case, HHS has no authority over the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), created by President Jimmy Carter’s executive order in 1979 and now part of the Department of Homeland Security. According to FEMA’s website, it “coordinates the federal government’s role in preparing for, preventing, mitigating the effects of, responding to, and recovering from all domestic disasters, whether natural or man-made.”

The dilemma of restraining government is often expressed by asking: who will guard the guardians? In modern government—well-meaning but often badly designed—hopes for governmental efficacy require the question: who will coordinate the coordinators? Across the numerous federal agencies that have some significant degree of responsibility for responding to an epidemic, there are “dozens of intelligent and accomplished individuals…who are supposed to lead in a crisis,” the Cicero Institute’s Judge Glock has written. “The problem is that those people have no clear lines of authority about who is supposed to coordinate them or be in charge, and no clear plan to follow even if such authority were provided.”

Glock’s article, “Why Two Decades of Pandemic Planning Failed,” describes how various government bodies have written pandemic response plans since 9/11. Innumerable, unreadable, and unread, they take up shelf and hard-drive space, but are harmful rather than simply useless. It would be better, that is, to have no plan and no one in charge when a disaster strikes than to have numerous plans on file and numerous officials more or less responsible. At least in the former situation you have the latitude that comes from drawing up your response on a blank sheet of paper, rather than being required to waste time settling questions about objectives, chain of command, and jurisdiction.

Even for those responsibilities that were clearly CDC’s alone, the pandemic of 2020 showed it to be poorly prepared. The New York Times reported, for example, that the agency’s “antiquated data systems, many of which rely on information assembled by or shared with local health officials through phone calls, faxes, and thousands of spreadsheets attached to emails,” quickly proved unable to provide reliable, current information. CDC’s systems, some of which relied on 1990s technology, “could not produce accurate counts of how many people were being tested, compile complete demographic information on confirmed cases, or even keep timely tallies of deaths.” A high-school kid in Mercer Island, Washington, launched a website last December, ncov2019.live, that ended up drawing millions of visitors as people became aware that it was providing better information, faster, than the coronavirus data available on CDC’s website.

Nor did CDC fare better when it was required to interact with other federal agencies. By January 20 it had developed a test to determine whether a person was infected with coronavirus, a real achievement. But public health labs around the country that used the test quickly began to report that it was yielding a significant number of false positives. The problem was in contaminated test kits sent from CDC labs, not in the test’s design, but this explanation did not become clear for three months.

Given the urgent situation, the clear need was for other labs to devise a reliable test. One might suppose that this work would have intensified when HHS Secretary Alex Azar declared a health emergency on January 31. At that point, the suspect CDC test was the only one that had received FDA approval. The perverse effect of the emergency declaration, however, was to decelerate the entire test-development process, since it formally required the Food and Drug Administration to apply exceptionally stringent evaluation criteria. Like most bureaucratic rules, this one had a rationale: inaccurate tests would be especially harmful during a public health emergency, and unscrupulous operators might profit from the panic by making bad tests available.

But, also like most rules, it was capable of being applied in an obtusely literal way. University, hospital, and research center scientists who worked to develop a test while having to contend with FDA rules were forced to endure the equivalent of a month-long trip to the Department of Motor Vehicles. A University of Washington virologist spent more than 100 hours filling out the forms and collecting the data necessary for his lab’s application to begin administering a new test. The FDA then responded that before the application could be considered, he was required to “digitally copy the electronic documents he had emailed to the FDA, burn the copies onto a disk and mail the hard disk to an office in suburban District of Columbia,” according to the Washington Post.

After a crucial month when (we now know) coronavirus was infecting growing numbers of Americans but testing to see who had contracted it was effectively halted, FDA changed course. It announced on February 29 that clinical laboratories could begin administering new tests they had developed, provided they simply notified the agency that testing was underway, after which they would have 15 days to submit the paperwork. The testing delay was a debacle because early and ample tests would have reduced the need for the widespread quarantines that began mid-March: a communicable disease cannot be communicated by a person who doesn’t have it. But if there’s no way to know whether someone has it, the risk-averse fallback is to treat everyone as a prospective Typhoid Mary, requiring mass lockdowns and the wearing of face masks.

Bureaucracy

How much blame does Donald Trump deserve for this tangled mess of responsibilities and missions, which led to the crucial agencies’ subsequent errors in responding to COVID-19? The pandemic happened on his watch and made clear how poorly prepared our government structures were to react to such an emergency. Few of his critics will see the need to inquire further: if Trump wanted to drain the swamp, he should have then built a state-of-the-art, fail-safe hydraulic system in its place. As Truman also said, famously: the buck stops here.

A more realistic assessment begins with political scientist James Q. Wilson’s observation in Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do and Why They Do It (1989): no president is going to spend much time, or devote much of his advisors’ time, to anything other than the biggest questions and the biggest departments that deal with them, such as Defense, State, and Treasury. “He is not likely,” Wilson wrote, “to be inclined toward nor rewarded for, fixing up the Park Service, redirecting the Securities and Exchange Commission, or improving the management of the Labor Department.”

Reforming an agency like CDC or FDA is especially thankless, since they are what Wilson called “procedural organizations,” ones where “managers can observe what their subordinates are doing but not the outcome (if any) that results from those efforts.” The CDC between epidemics is like the military between wars: “Every detail of training, equipment, and deployment is under the direct inspection of company commanders, ship captains, and squadron leaders. But none of these factors can be tested in the only way that counts, against a real enemy, except in wartime.”

Absent empirical evidence to evaluate how they’re performing, procedural organizations become especially committed to outputs rather than outcomes: processes and practices, as opposed to results. The FDA’s infuriating decision to impede rather than facilitate the development of coronavirus tests shows that such organizations are deeply committed to the bureaucrat’s maxim: never do anything for the first time. In the event that Bill Clinton actually reinvented government in the 1990s—leaving it nimble and responsive, alert to changing developments, constantly aware of the big picture—government appears to have de-invented itself with a vengeance.

The more likely explanation is that government reform cannot succeed unless it amasses forces that are stronger than the powerful ones that make government the way it is. “We ought not to be surprised that organizations resist innovation,” Wilson wrote. “They are supposed to resist it.”

The reason an organization is created is in large part to replace the uncertain expectations and haphazard activities of voluntary endeavors with the stability and routine of organized relationships. The standard operating procedure (SOP) is not the enemy of organization; it is the essence of organization.

There will be a certain symmetry if bureaucratic SOPs bring about the end of Donald Trump’s political career, since they were central to the beginning of it. By May 1986 New York City’s government had spent six years and $12.9 million attempting to reopen Wollman Rink, Central Park’s ice-skating venue, after its concrete floor buckled in 1980, closing the facility down. Trump, then a celebrity real estate developer, made an offer and subsequently struck a deal with the city: his contractors would finish the job in six months for $3 million. Trump would pay for any cost overruns and, in return, secure leases to operate the rink and an adjacent restaurant. Trump’s company finished the job in four months, some $750,000 under budget, and the rink was in use by November 1986. More than just a publicity coup, the Wollman Rink episode gave Trump a uniquely powerful claim to having validated the accusation that we are governed by idiots, which became central to his presidential campaign 30 years later.

As Wilson points out, however, every roadblock that kept the city from finishing in six years a job that Trump completed in four months had a history and a rationale. That is, “Every restraint and requirement originates in somebody’s demand for it.” Trump could pick his own general contractor, for example, who could pick his own subcontractors. The city’s Parks and Recreation department, by contrast, was forbidden by law—a law passed to combat cronyism—from hiring a general contractor. Instead, Wilson explains, the department was legally required “to put every part of the job out to bid and to accept the lowest without much regard to the reputation or prior performance of the lowest bidder.” Trump’s contractor for the Wollman Rink renovation, reflecting on his advantages vis-à-vis public sector officials taking on the same assignment, said, “The problem with government is that government can’t say ‘yes’…. There are fifteen or twenty people who have to agree.”

Surely, a global pandemic must qualify as an emergency that justifies “cutting the red tape”: setting aside standard operating procedures like the FDA’s requirements on the laboratories developing tests for the virus. But that’s not so simple, either. “[N]o rule can be promulgated that tells you when promulgating rules is a good idea,” Wilson observes. The corollary is that it is, at the least, very hard to devise a rule that specifies under what circumstances an agency should disregard its ordinary rules. Such a rule wouldn’t solve the problem so much as create a meta-problem: the rules exist in the first place because they reflect settled judgments about the areas where we don’t want officials making it up as they go along. If we give those officials wide latitude to ignore the rules when they believe the circumstances demand it, there’s little point to having the rules in the first place. But if the corrective for that problem is to write elaborate rules about when, and under just what circumstances, it is acceptable to disregard the rules, the complexity of the override procedure defeats the purpose. The FDA’s hybrid approach appears to have been reliance on an elaborate set of procedures for ordinary circumstances—to be set aside in favor of a different set of elaborate procedures during a public health emergency.

Think Globally

A fair objection to this inquiry is that it is less important to compare America’s COVID-19 response to some Platonic ideal of an omnicompetent government than to compare it with other countries around the world. Such comparisons show that some nations appear to have been affected more severely than America by SARS-CoV-2, but that it has been less devastating in a number of other countries. The Worldometer website, updated daily, shows that Belgium, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy all have COVID-19 death rates (deaths per million people in the national population) at least 34% higher than the U.S. rate. France’s rate is about 7% higher than America’s. (Death rates, though not wholly reliable, are more useful than comparing the number of people diagnosed as having contracted the virus. The latter figure is suspect because it is hard to know whether a high case rate reflects widespread infection or widespread testing.) On the other hand, Canada’s death rate is about 54% of America’s, Germany’s about 25%, and the death rate in Japan and South Korea is less than 2% of the U.S. rate.

Such figures make it possible to say that America’s coronavirus failure is simply the failure to respond the way governments did in countries where the pathogen took fewer lives. But matters are not so simple, and just emulating one of those nations would not have been so easy. Part of the problem is one already discussed, the difficulty of knowing things. It’s unclear why, or even to what extent, death rates are different in different countries. International comparisons aren’t reliable if different countries count COVID deaths using different criteria.

The hard question, which admits of various answers and approaches, is whether a person has died of the pathogen or with it. Belgium for example, has the highest COVID-19 death rate of any country in the world (except for the micro-polity of San Marino), a rate 96% higher than America’s. But it is not clear how much this rate owes to the disease’s virulence there, and how much to official decisions about recording data. One Belgian virologist all but boasted that juking the stats generated political pressure for more health care spending. “We do this because we want to save lives.” The result is that Belgium’s death statistics include many people, especially elderly people, who died with, and in some cases from, diabetes, heart disease, and other problems. One public health official said that, as a result, the first step in comparing Belgium’s data to that of other countries required dividing its official death statistics in half.

Beyond the problem of having limited confidence in how seriously the virus has affected different countries, there’s a further difficulty. It’s not clear how, and to what extent, anything governments did or failed to do affected these differences. Spain’s COVID-19 death rate, for example, is 3.7 times as high as Portugal’s, though there is no obvious explanation that would account for the virus having such different impacts on the Iberian Peninsula.

Similarly, several observers have argued that South Korea had many fewer infections and deaths than the U.S. because of its superior government response to the crisis. South Korea relied on testing early and widely. Armed with the resulting data, it then isolated people who tested positive while aggressively tracing everyone each infected person had had contact with, in order to quickly identify other people who might be transmitting the virus. As of this writing, South Korea’s COVID-19 death rate is six per each million residents, compared to America’s 431.

But Japan’s death rate, eight per million, is only slightly higher than South Korea’s, despite the fact that Japan reacted far more passively, and did so with one of the world’s oldest populations, which should have made the country especially vulnerable. Even as “nations were exhorted to ‘test, test, test,’” according to Bloomberg News, “Japan has tested just 0.2% of its population—one of the lowest rates among developed countries.”

Indonesia has a COVID-19 death rate of 15 per million, making it one of the “countries that should have been inundated [but] are not,” the New York Times reported, “leaving researchers scratching their heads.” One Indonesian expert complained, “we have a health minister who believes you can pray away COVID, and we have too little testing.” Perhaps, he speculated, the country is made up of so many islands that its geography limits transmission of the virus. “There’s nothing else we’re doing right.”

Even if one stipulates, for the sake of the argument, that America could have approximated South Korea’s coronavirus outcome if it had duplicated that country’s governmental response, it does not follow that this was ever a politically feasible path. A democratic nation’s policy options are limited to ones the citizenry considers understandable and justifiable. This means that no president or cabinet secretary has the ability to simply order up a policy response that the people will find inexplicable or intolerable. To paraphrase former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, you go into a pandemic with the nation you have, not the nation you might want or wish to have.

The proximate reason South Koreans were amenable to their government’s aggressive response to the latest threat was that the country had suffered from several recent contagious outbreaks: SARS in 2002, H1N1 in 2009, and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015. Canada also found itself afflicted with and unprepared for SARS, and changed its public health policies in response.

For whatever reason—luck being the leading candidate—these contagions affected the U.S. less severely, which meant that prior to 2020 most Americans had never before experienced a public health crisis as extensive, sudden, and frightening as COVID-19. Combine the experience of such good fortune with normalcy bias, and Americans were unlikely to have been receptive to any elected official’s demands for preventive measures that entailed high expenses and significant dislocations.

The South Korean public, by contrast, not only accepted but demanded changes meant to correct what were perceived as deficiencies during the MERS response. Among them: extensive testing, including the use of unapproved diagnostic tests in an emergency; giving health authorities “warrantless access to [closed-circuit television] footage and the geolocation data from the new patients’ phones,” in the words of the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson; and “new laws [that] required local governments to send prompt alerts, such as emergency texts, to disclose the recent whereabouts of new patients.”

Simply listing such practices conveys why they would have met political skepticism and opposition in the U.S., over and above the resistance caused by the absence of recent epidemics. Public opinion surveys, which showed in the 1950s and ’60s that a healthy majority of Americans trusted government, have found such trust to be a minority position for nearly 50 years. In 27 surveys taken from 2010 to 2019, the percentage of Americans who trusted government always or most of the time ranged from 10 to 29%. South Korea’s public health policy of “test, trace, and isolate” requires a high degree of voluntary cooperation, which means a high degree of citizens’ confidence in their government. There are reasons we might wish for Americans to revert to the attitudes they held 60 years ago, but no reason to think that an official today can simply ignore the fact that they haven’t.

Keith Humphreys, a Stanford professor who studies public health, contends that Americans’ “concerns about privacy and autonomy,” more acute than in other democracies, are a major impediment to test, trace, and isolate. Such policies’ effectiveness depends on “people being so compliant that they will stay home for 14 days because a health worker told them to.” But what if they don’t? “What do you do when millions of Americans refuse to take your tests? What do you do when many of the people you order to isolate, or to close their business, angrily refuse?”

It’s hard to imagine a more fundamental conflict. Humphreys says that like other democracies in the region, such as Taiwan and Singapore, South Korea has an “authoritarian residue.” By contrast, the feisty, distinctively American attitude is Don’t Tread on Me. As with the 55-mile-per-hour speed limit, Americans will probably work out an accommodation between freedom and safety—eventually. It should come as no surprise that we failed to do so immediately.

Act Federally

It is also the case that America went into the coronavirus pandemic with the Constitution it had, not a theoretical alternative that some might have wished it had. After three years of denouncing him as a dictator, Donald Trump’s critics pivoted adroitly to denouncing him for not being enough of one. In the New Yorker, Harvard Law professor Jeannie Suk Gersen described the COVID-19 emergency as “that rare crisis that is truly national, where the response of a state may ultimately be only as effective as the response of other states.” She lamented that Trump “has been strikingly uneager to wield federal executive power in this crisis,” before casting about for some—any—legal and constitutional basis for him to do so. But she did acknowledge that under the Constitution the states retain “the power to issue all manner of regulations related to people’s well-being, including public health and safety.” As a result, “there is currently no legal authority for Trump to control when or how states will ease their restrictions” on access to mass transit, shops, and other public spaces, which presumably means that there is currently no legal authority for Trump to require states to impose such restrictions.

Thus, Suk Gerson reluctantly endorses the view of another law professor, John Yoo of the University of California, Berkeley, that the federal government “has only limited powers to respond to a pandemic.” The constitutional constraints have begotten practical ones: the states possess the resources to respond to a public health crisis, but the federal government does not. “The New York City Police Department,” Yoo points out, “has more sworn officers than the FBI’s entire workforce.”

In fact, it appears that COVID-19’s lethal impact in America is largely a function of the way it ravaged the New York metropolitan area. This is so for two reasons, statistical and epidemiological. The Worldometer data shows that the three states (Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York) whose population totals are dominated by New York City’s five boroughs and hundreds of suburbs account for just under 10% of the national population but more than 36% of America’s COVID deaths. If those three states were a separate nation, its COVID death rate would be more than 1,650 per million, a figure far above anything even Belgium’s creative data manipulation could attain. Conversely, the other separate country created by those states’ secession, America Lite, would be left with a COVID death rate of 302 per million—30% lower than America’s current rate, some 82% less than the collective figure for the three states, and about 29% more than Canada’s rate.

Furthermore, it appears that America Lite would have even lower numbers of coronavirus infections and deaths if it had cut itself off from Greater NewYorkistan economically and socially as well as politically. The New York Times reported in May on a study that used “signature mutations of the virus, travel histories of infected people, and models of the outbreak by infectious disease experts” to conclude that New York City “became the primary source of new infections in the United States…as thousands of infected people traveled from the city and seeded outbreaks around the country.” In this light, the single most effective step that President Trump could have taken against the spread of coronavirus would have been to shut down travel in and out of New York: airports, trains, and highways. He raised the possibility in March, but never followed through. Yoo states flatly that the federal government has the authority to “bar those who might have the coronavirus from…traveling across interstate borders,” while Suk Gerson limits herself to noting New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s assertion that cutting his state off from the rest of the country would be “a federal declaration of war on states.”

Reasonable Doubt

Politico’s founding editor, John F. Harris, recently invited readers to “make the case that Trump’s pandemic performance has been satisfactory.” What I’ve outlined here criticizes that challenge rather than responds to it. Since the burden of proof in trials is on the prosecution, not the defense, the better question is whether Trump’s many critics have proven beyond a reasonable doubt that his administration’s response to the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 has been unsatisfactory.

I submit that there are too many reasons to doubt this proposition for an open-minded juror to vote for conviction. Any real government, as opposed to an imaginary omnicompetent one, would have faced the same constraints American government did under Trump this year: acquiring and interpreting crucial data, making hard choices involving tradeoffs between competing imperatives, and inducing the vast, unwieldly government apparatus to respond flexibly and forcefully to a sudden crisis.

Any president would have gone into the pandemic with the federal bureaucracy he had, not the one he wished he had. Even if, improbably, Trump had made it his highest priority upon taking office in 2017 to reform it, that work would have been far from completion by 2020. One lesson of the pandemic is that many of the federal agencies on which Americans depend are deeply flawed, by virtue of vague, overlapping missions, as well as operational capacities ill-suited to their discharging their responsibilities. It is also clear, however, that they are so deeply flawed that redirecting these bureaucracies from their present course is work that, if it is to happen at all, a series of presidents will have to make a high priority, with the cooperation of a series of congressional leaders.

Actual governments around the world did respond to the COVID-19 crisis, with widely varying outcomes. There’s no clear reason to believe, however, that the severity of the pandemic in any particular country is solely or even primarily a function of how its government acted. It is especially prudent to refrain from issuing final grades to national governments until more time passes and more information becomes available about the course of the disease. If there are future waves of infections, countries may fare very differently than they have so far.

There is no prospect that Trump’s enemies will qualify their criticism of him in light of these mitigating circumstances. The outrage appears, to say the least, selective. Many would clearly prefer France’s comprehensive welfare state to America’s, and a technocratic president like Emmanuel Macron to a bombastic one like Trump. But even though COVID-19 has been a bigger, more lethal problem in France than in America, none of Trump’s American critics appears to be incandescent with rage at Macron, or to scorn him as the corrupt, stupid leader of a failed state.

However the voters assess Trump in November, the politicians who go to work after the election will have to make our federal and state governments better prepared for the next public health crisis than they were for this one. Unfortunately, lack of preparation is a venerable American tradition. Harris points out that America’s army was smaller than Portugal’s prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor. In 1941 we had the time and distance to recover. Today’s smaller, interconnected world is far less forgiving.