Discussed in this essay:

The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D'oh! of Homer, edited by William Irwin, Mark T. Conrad, and Aeon J. Skoble.

Created By: Inside the Minds of TV's Top Show Creators, by Steven Priggé.

The Showrunners: A Season Inside the Billion-Dollar, Death-Defying, Madcap World of Television's Real Stars, by David Wild.

Dialectic of Enlightenment, by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, translated by Edmund Jephcott.

"How to Look at Television," in The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture, by Theodor Adorno.

Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, by Henry Jenkins.

Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture, by Henry Jenkins.

Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera, by Jennifer Hayward.

If you can tear yourself away from your favorite television shows long enough to wander down to your local bookstore, you will be amazed at all the books you'll find these days—about your favorite television shows. The medium that was supposed to be the archenemy of the book is now giving an unexpected—and welcome—boost to the publishing industry. It is well known that for the genre of literary criticism, publishers are extremely reluctant to bring out what are called monographs—books devoted to a single author or a single work (unless that single author is Shakespeare or the single work is Hamlet). Those works of literary criticism that are published often come out in print runs that number in the hundreds. By contrast, a book devoted to a single television show, The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D'oh! of Homer(2001, published by Open Court and edited by William Irwin, Mark T. Conard, and Aeon J. Skoble), has reached its 22nd printing and its sales number in the hundreds of thousands.

Partly inspired by the success of The Simpsons volume, three serious publishing houses—Open Court, Blackwell, and University Press of Kentucky—currently have series on philosophy and popular culture, with volumes devoted to such TV shows as Seinfeld, The X-Files, The Sopranos, South Park, Battlestar Galactica, Family Guy, and 24. These volumes use moments in the shows to illustrate complicated issues in ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology. Books from other serious publishers analyze the shows themselves, often using sophisticated critical methodologies originally developed in literary theory.

TV Grows Up

This publishing phenomenon has been little noted; what are we to make of the surprising synergy that has been developing between television and the book? The answer is that the proliferation of serious books about television is a clear sign that the medium has grown up and its fans have grown up with it. Many of the publications in question are guidebooks to individual shows, containing episode-by-episode plot summaries, cast lists, critical commentaries, and other scholarly apparatus, including explanations of recondite cultural references and allusions in the programs. No one ever needed a guidebook to I Love Lucy. If you couldn't tell Fred Mertz from Ricky Ricardo, you probably couldn't read in the first place. But with contemporary shows such as Lost, even devoted fans find themselves bewildered by Byzantine plot twists, abrupt character reversals, and dark thematic developments. Accordingly, they welcome whole books that try to sort out what is happening in their favorite shows and to explain what it all means. The fact that we now need books to explain our favorite TV shows suggests that the best products of the medium have developed the aesthetic virtues we traditionally associate with books—complex and large-scale narratives, depth of characterization, seriousness of themes, and richness of language.

I am not insisting that the general artistic level of television has risen; only that, like any mature medium, it has reached the point where it can serve as the vehicle for some true artists to express themselves. Even so, for those who have not been watching television lately and may be understandably skeptical of my claim, I need to explain what has changed in the medium to make it more sophisticated than it used to be, at least in its best cases. A lot of the change has been driven by technological developments. Whereas in its initial decades television programming was largely controlled by the Big Three networks, CBS, NBC, and ABC, the development of cable and satellite transmission has made hundreds of channels available, and vastly increased the chances of innovative and experimental programming reaching an audience. To be sure, the hundreds of channels now spew out a greater amount of mindless entertainment than ever before, and often end up recycling the garbage of earlier seasons. But the move from broadcasting to narrowcasting—the targeting of ever more specific audience segments—has allowed TV producers to aim an increasing number of programs at an educated, intelligent, and discriminating audience, with predictably positive results in terms of artistic quality.

During the same period, the development of VCRs and then DVRs, as well as videocassette and DVD rentals and sales, has freed television producers from earlier limits on the complexity of their programs. In roughly the first three decades of television history, if viewers missed a show in its initial broadcast slot, they had little chance of seeing it again; at best they had to wait months for a summer rerun. As a result, producers tended to make every episode of an ongoing series as self-contained and as easily digestible as possible. But the proliferation of forms of video recording has made what is known as "time-shifting" possible. Viewers can now watch a show whenever they want and can easily catch up with any episodes they have missed (a survey in TV Guide revealed that 22% of Lost viewers now watch the show on DVR within seven days of its original air date). Some viewers have chosen to skip television broadcasting entirely and to watch shows only when they come out on DVD, a procedure that facilitates a much more concentrated experience of the unfolding of plot and character. Thus producers are now much freer to introduce elements of complexity into their shows, including elaborate plot arcs that may span an entire season—with confidence that viewers can handle such complications. With the advent of DVDs, television shows can now be "read" and "re-read" just like books—one reason why academic writing about television has suddenly flourished. What cheap paperbacks once were to literary scholarship, the DVD now is to television scholarship.

A Writer's Medium

The various changes in the way people watch television have made the medium much more attractive to creative talent. At the same time, Hollywood executives have discovered that what makes a TV series succeed from season to season is above all good scripts. As a result, in Hollywood circles, television is now known as a writer's medium. In movies, the director generally calls the shots, largely determining what finally appears on screen. That is why we know the names of individual motion picture directors, but are seldom aware of the screenwriters, even at Oscar time. The situation is just the reverse in television, where almost nobody knows who directs individual episodes of a series, but the writer-creators become famous—such as Chris Carter (The X-Files), Joss Whedon (Buffy the Vampire Slayer), and David Chase (The Sopranos). This situation is admittedly complicated by the fact that some television writers occasionally direct episodes of their shows themselves. Nevertheless, in television the way to have a lasting and creative impact is fundamentally as a writer, and Hollywood has come to value good TV writers accordingly. In an interview in the Los Angeles Times last April, Sue Naegle, the new chief of HBO Entertainment, said: "Development by committee or by patching together multiple people's ideas isn't the way to get great television. I think it starts with the writer. Somebody who's very passionate and has a clear idea about what they'd like to do and the kind of show they'd like to produce."

A writer who creates a show often becomes what is called in Hollywood a "showrunner"—the one who puts together all the elements needed to bring the vision of a series to the screen. (For accounts of the role of showrunners, two useful books are Steven Priggé's Created By: Inside the Minds of TV's Top Show Creators, 2005, and David Wild's The Showrunners, 1999.) A good showrunner becomes responsible for the artistic integrity of his work in a way that no motion picture screenwriter can ever hope for. The TV showrunner has become the true auteur in the entertainment business, to use the favorite term of fancy French film theory.

As a result, creative writers are increasingly migrating to television, and it is attracting a higher level of talent than ever before. Today's TV writers are routinely college-educated and often have higher degrees in television writing from schools like USC and UCLA. The writing staff of The Simpsons has a high concentration of Harvard graduates, as witness all the jokes in the series at the expense of Yale. An excellent example of the new level of academic credentials of showrunners is David Milch, who served as writer-producer on Hill Street Blues and NYPD Blue and created a genuine television masterpiece in Deadwood. Milch graduated summa cum laude from Yale as an undergraduate, went on to get an MFA from Iowa, became a creative writing instructor at Yale, and even worked with Robert Penn Warren revising a literary anthology. In his book Deadwood: Stories of the Black Hills, Milch cites an impressive literary pedigree for his Western series:

The number of characters in Deadwood does not frighten me. The serial form of the nineteenth century novel is close to what I'm doing. The writers who are alive to me, whom I consider my contemporaries, are writers who lived in another time—Dickens and Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and Twain.

If academics are now finding material worth studying in television shows, one reason is that writers like Milch are putting it there.

Germany vs. Hollywood

The growing sophistication of television illustrates a general principle of media development. Every medium has a history, no medium has ever emerged full-blown at its origin, all media develop over time, and they only gradually realize their potential. For some of the traditional media, their origins are mercifully shrouded in the mists of time. The earliest Greek tragedies we have are by Aeschylus, and they are magnificent works of art indeed. But they by no means represent the primitive stages in the growth of the form. If we did have the very first tentative steps toward Greek tragedy, we might be appalled at their crudeness and finally understand why this genre we respect so much bears a name that means in Greek nothing more than "goat song." By contrast, television had the great historical misfortune of being born and growing up right before our eyes, and many intellectuals have never forgiven the medium its birth pangs.

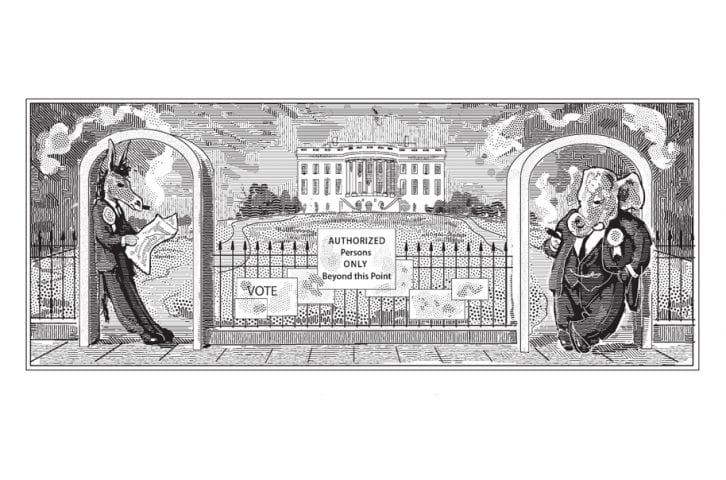

Television's problem with its reputation was compounded by the fact that it was the new kid on the media block at just the moment when Cultural Studies in its modern sense was hitting its stride and gearing up to criticize the American entertainment industry. It found its perfect whipping boy in television. I am talking about the Frankfurt School and its chief representative in America: Theodor Adorno. In 1947, he published, along with his colleague Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, which contains a chapter called "The Culture Industry"—perhaps the single most influential essay in Cultural Studies of the 20th century. It epitomized, established, and helped promulgate the tradition of studying pop culture as a debased and debasing mass medium. In this chapter, Horkheimer and Adorno write primarily about the motion picture industry, which they, as German émigrés living in the Los Angeles area during World War II, had a chance to observe firsthand. In terms that have become familiar and that reflect their left-wing biases, they present Hollywood as a dream factory, serving up images of desire that provide substitute gratifications for Americans exploited by the capitalist system, and thereby working to reconcile them to their sorry lot.

In 1954, Adorno published on his own an essay entitled: "How to Look at Television" in The Quarterly of Film, Radio, and Television, which extends the Frankfurt School analysis of the culture industry to the new medium. Adorno may well be the first major intellectual figure to have written about television and to this day I know of no one of comparable stature who has dealt with the medium. His essay set the standard and the tone for much of subsequent analysis of television and remains influential.

As always with Adorno, his television essay is in many respects intelligent and perceptive. He does an especially good job of analyzing the ideological work accomplished by various television shows in getting Americans to accept the dull routine of their daily lives. But Adorno shows little awareness that he is dealing with a medium in its earliest stages, that it might develop into something more sophisticated and genuinely artistic in the future. Admittedly, at the end he speaks of the "far-reaching potentialities" of television, but he expects it to improve only because of critics like him, not because of any developmental logic internal to the medium. He hopes that through his essay "the public at large may be sensitized to the nefarious effect" of television, presumably so that government regulation can do something about it. He would not dream that the commercial pressures on an entertainment medium could by themselves improve its quality.

When Adorno was writing in 1954, broadcast television was less than a decade old as a commercial enterprise and still groping toward a distinct identity. As with any new medium, it remained in thrall to its predecessors, following what turned out in many ways to be inappropriate models. In particular, early television modeled itself on radio, structuring itself into national broadcasting networks (in several cases derived directly from existing radio networks) and reproducing radio formats and genres—the game show, the quiz show, the soap opera, the talk show, the variety program, the mystery, and so on. Some of the most successful of the early television shows, such as Gunsmoke, were simply adapted from radio precursors.

The Cultural Pyramid

Thus at several points in the essay Adorno stigmatizes television for features that turn out to have merely reflected its growing pains. For example, he condemns television for creating programs of only 15 or 30 minutes duration, which he correctly views as inadequate for proper dramatic development but incorrectly views as somehow an inherent limitation of the medium. He had no idea that television was soon to move on to one— and even two-hour dramatic formats, and that it eventually was to develop shows like The X-Files or Lost with a full season arc of episodes—some of the largest scale artistic productions ever created in any medium, comparable to Victorian novels in scope.

Elsewhere Adorno dogmatically proclaims: "Every spectator of a television mystery knows with absolute certainty how it is going to end." This may have been true when Adorno was writing (personally I doubt it), but try telling it to fans of the aptly named Lost today. They are not just mystified about how the series is going to end way off in the future; they are not even sure what is going on in the present. Or consider the recent furor over the final episode of the final season ofThe Sopranos. For weeks media pundits speculated about how the series was going to end, but they all proved wrong, and everybody was shocked by a kind of abrupt conclusion that was unprecedented in television history. This surprising turn in The Sopranos is exactly what one would expect at a later stage of a medium, when producers, for both artistic and commercial reasons, deliberately thwart their audience's expectations in order to generate interest. Amazingly, for a sophisticated Marxist, Adorno does not appear to grasp that media have histories.

Insisting that television is inferior to earlier examples of popular culture, Adorno contrasts 18th-century English novels favorably with the TV shows he was watching in the early 1950s. But his examples of the popular novel are all drawn from the work of Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding—the three greatest English novelists of the 18th century. And Adorno compares them to the most mindless sitcoms and game shows he can find in the earliest days of American TV. Too many intellectuals like Adorno score points against television by comparing the apex of achievement in earlier media with the nadir of quality in television. Television is a voracious medium. It now requires filling up hundreds of channels 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The result is that television does show a lot of junk. But inconsistency in quality has always been the bane of any popular medium. For every one of Shakespeare's masterpieces, the Elizabethan theater turned out dozens of potboilers that share all the faults of the worst television fare (gratuitous sex and violence, stereotyped characters, clichés of plot and dialogue). For every one of Dickens's great works, the Victorian Age produced hundreds of penny dreadfuls, trash novels that have been justly condemned to the dustbin of history. A living culture always resembles a pyramid, with a narrow pinnacle of aesthetic mastery resting on a broad base of artistic mediocrity.

Adorno's contempt for American television leads him to treat it in an unscholarly manner. He does not even bother to name the particular shows he is discussing because evidently they all pretty much looked the same to him. One of his examples must be a sitcom I remember called Our Miss Brooks. Here is Adorno's capsule description: "the heroine of an extremely light comedy of pranks is a young schoolteacher who is not only underpaid but is incessantly fined by the caricature of a pompous and authoritarian school principal." I have trouble recognizing the show I remember with some fondness in Adorno's characterization: "The supposedly funny situations consist mostly of her trying to hustle a meal from various acquaintances, but regularly without success." One begins to suspect that Adorno's readings of American television are telling us as much about him as they do about television. I hate to think that the great anti-fascist intellectual had an authoritarian personality himself, but he seems to be suspiciously unnerved by the typically American negative attitude toward authority figures, especially when he sees it displayed by women. Could it be that when Adorno looked at Principal Osgood Conklin of Our Miss Brooks, he was having flashbacks to Professor Immanuel Rath of The Blue Angel, and couldn't bear the image of academic authority humiliated by underlings and students? After all, Germans have always respected their teachers much more than Americans do. One shudders to think what Adorno would have made of Bart Simpson's treatment of Principal Seymour Skinner.

Strange Customs of an Alien Tribe

As one reads Adorno on American television, one gradually begins to realize that he is writing about the subject as a foreigner. Indeed, he resembles an anthropologist trying to describe what are for him the strange customs of an alien tribe. All the symptoms of cultural displacement are there—he doesn't find the local jokes funny, differing cultural products look alike to him, he claims to understand the artifacts better than do the people who create and use them, and so on. Standing far above the cultural phenomena he is analyzing, he is quite eager to criticize them and unwilling to appreciate them in their own terms. He does not think of television programs as the product of individual creators and thus has no interest in their distinct identities. In rejecting what would normally be congenial to him—a Freudian analysis of television—Adorno writes: "To study television shows in terms of the psychology of the authors would almost be tantamount to studying Ford cars in terms of the psychoanalysis of the late Mr. Ford." With his conception of the culture industry, Adorno regards television shows as mass-produced and thus completely without any individuality or distinct identity—in short, without a name.

Adorno ignores the promising developments that would have been evident to any sympathetic observer in his day. Sid Caesar, along with writers of the caliber of Mel Brooks and Neil Simon, was already creating some of the most inventive comedy ever to appear on television. And waiting in the wings in the 1950s was the first authentic genius of the medium, Ernie Kovacs. He pioneered many of the camera techniques that have become standard on television, and later was the first person to realize the potential of videotape for special effects, particularly in comedy. One of Kovacs's greatest television achievements was to create what would today be called a video to the music of Bela Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra. With Adorno's love of modernist music, here was a television moment he might have appreciated, although I'm afraid he would have dismissed it as just another cheap popularization of classical music, like the American performances of the Budapest String Quartet, which he scorned as too slickly commercial. Adorno condemned even as great a conductor as Arturo Toscanini because he worked for the National Broadcasting Corporation.

I don't mean to berate Adorno for what he missed in the early days of television. He was after all a German émigré, whose command of English was no doubt shaky, particularly of the kind of colloquial idiom necessary to understand comedy in any medium. (I have noticed that Adorno never finds anything funny in American pop culture, not even Donald Duck.) Adorno was doing his best under difficult circumstances to understand phenomena that were profoundly alien to him. But the problem is that the work of this German émigré on American pop culture became the prototype of academic studies of television for decades, and we are still struggling to get out from under his influence. The idea that television is limited to stereotypes, that it is in its very nature as a medium artistically inauthentic, that it serves only the interests of a ruling elite, that it is ideologically reactionary—all these ideas are the intellectual legacy of Adorno, and they are still repeated by many critics of television today.

Taking the Fan's Perspective

Adorno's television essay is unfortunately typical of the way intellectuals have dealt with new media over the centuries. When a new medium comes along, intellectuals, trapped in modes of thinking conditioned by the old media, tend to dwell obsessively on the novelty of the medium itself, focusing on the ways in which it fails to measure up to the standards of the old media. Early talking films often seemed like badly staged plays, and early television shows often looked like anemic movies. Fortunately, as a medium matures, it seems to breed a new generation of critics who are able to appreciate and articulate its distinctive and novel contributions. That is what is happening in television criticism today.

As a turning point, I would cite particularly the work of MIT Professor Henry Jenkins in such books as Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (1992) and Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture (2006). Jenkins shows that it is not just the producers in television who can be creative, but the fans as well. Jenkins demolishes the great myth of the Frankfurt School—the myth of the passive consumer. For Adorno, television viewers sit captive in front of the screen, mesmerized by its images, allowing themselves to be shaped in their desires and their ideas by its overt and covert messages. He repeatedly compares American television to totalitarian propaganda. Unlike Adorno—who merely posits what the television viewer is like—Jenkins has studied and chronicled in detail how real people actually react to the television shows they watch. And what he has found is active, rather than passive consumers—fans of shows who take possession of them—his "textual poachers." They quarrel with producers over new story lines, come up with variations of a show's plots in their own self-published magazines, and develop the characters in directions their creators could never imagine. Jenkins persuasively argues in favor of taking the fan's perspective in analyzing television—and this is the cornerstone of the new turn in Cultural Studies. Academics are now writing about television shows because they admire them, not because they hate the medium. They write out of genuine knowledge of and sympathy for a particular show—they even call it by name.

One of the best books I know on participatory culture is Jennifer Hayward's Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera (1997). As her title indicates, in discussing the serial form as basic to modern culture, Hayward finds continuities between the serial publication of Victorian novels and the serial broadcasting of TV soap operas. She thus cuts across the conventional divide between high culture and popular culture that so many critics of television labor mightily to maintain. With painstaking scholarship and archival research, she demonstrates how serial forms make possible productive feedback loops between creators and their audience, thus driving a continual process of refinement and improvement in modern media.

There are of course potential pitfalls in adopting the fan's perspective in academic criticism—a loss of objectivity and the ever present danger of taking a show too seriously, and treating a passing fad as of lasting significance. But as we have seen, the Olympian stance of an Adorno has its problems too—he is so far removed from the phenomena he is analyzing that he ends up out of touch with them, unable to separate the wheat from the chaff. We never object when literary critics write about Shakespeare's plays as "fans." In fact we assume that a Shakespeare scholar admires the plays, and expect to broaden and deepen our own appreciation of them by reading Shakespeare criticism. In many ways, the new writers about television are performing a traditional critical function. They are trying to separate the outstanding from the ordinary, the creative from the banal.

As a result, some of the best "literary criticism" today is paradoxically being written about television. Many literary critics seem to have become bored with their traditional role as the interpreters of great literature, and now are as interested in tearing authors' reputations down as they once were in building them up. In the era of literary deconstruction, it can be refreshing to turn to television books and see critics who are still interested in reconstructing the meaning of the works they discuss. The readers of the new books on television will accept no less, since their reason for turning to these books is to help them better understand their favorite programs. At a time when literary critics often seem to be talking only to each other, the lively market for television books tells us something. The reading public is still interested in thoughtful intellectual conversation about what has always made for good narratives in any medium—complex plot lines, interesting characters, serious and even philosophical issues, and insights into the human condition.