Books Reviewed

In the Middle East, the past bears upon the present with special intensity. Sixty years on, the Arab-Israeli war of 1948—which Palestinians call al-nakba, or the catastrophe, and Israelis call the War of Independence—still nourishes irreconcilable interpretations of the conflict it inaugurated. However one reads the story of that confrontation—as stirring national liberation or as deliberate ethnic cleansing, as immaculate conception or original sin—this first chapter in an ongoing drama determines how one regards Israel itself. A new book, the most comprehensive so far on the subject, pairs this most contentious war with Israel’s most contentious historian.

In the turbulent wake of his much-discussed 1988 book, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, Benny Morris, a kibbutz-born, Cambridge-educated professor of history at Ben-Gurion University, surfaced as the most influential of Israel’s revisionist New Historians. Aided by newly opened Israeli archives, this group of younger scholars, including Avi Shlaim, Tom Segev, and Ilan Pappe, called into question the country’s cherished founding myths, and the assumptions of its collective memory.

Much to the delight of Israel’s post-Zionist intelligentsia, Morris claimed that a policy advocating “transfer” of Palestinians was built into Zionism, which he described in Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–2001 (2001), as “a colonizing and expansionist ideology and movement…intent on politically, or even physically, dispossessing and supplanting the Arabs.” In blaming Israel—and its first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, whom he painted in Machiavellian shades—for the mass exodus of Palestinian refugees, Morris sought to expose a darker side of the story of 1948.

For this unmasking, Morris earned much praise from the Left. Edward Said, for instance, lauded him for showing “that it was a sequence of Zionist terror and Israeli expulsion that were behind the birth of the Palestinian refugee problem.” Just as predictably, Morris drew fire from mainstream Israeli historians like Shabtai Teveth, who dismissed Morris and the New Historians as peddling a “farrago of distortions, omissions, tendentious readings, and outright falsifications.”

After the failed Camp David summit in 2000, however, when Yasser Arafat turned down Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak’s offer of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and launched a second, bloodier intifada of suicide bombings, Morris abruptly revised his revisionism. He began to acknowledge a long thread of obduracy, folly, and rejection that ran through the entire history of Palestinian nationalism—”a rejection, to the point of absurdity, of the history of the Jewish link to the land of Israel; a rejection of the legitimacy of Jewish claims to Palestine; a rejection of the right of the Jewish state to exist.” The Palestinian leaders, he now saw, sticking fast to their vision of a Greater Palestine, rejected every compromise offered them, from the Peel Commission partition proposal of 1937 and the U.N. Partition Plan of 1947 to the peace proposals offered by Yitzhak Rabin at Oslo and Barak at Camp David.

Morris himself still advocated a Palestinian state, and considered the Israeli settlement movement misguided. But if in the 1990s he believed that the Palestinians had finally accepted the need for a compromise to achieve a two-state solution, by following the thread of their tenacious rejection of negotiated accommodation he now reluctantly concluded that they had all along ultimately sought Israel’s destruction. Morris became, in other words, a symbol of the Israeli Left’s disillusionment.

Morris’s about-face did not find favor in the eyes of his erstwhile colleagues. “Morris flipped out as a result of three years of terrorism,” Segev said. Pappe denounced Morris’s “abominable racist views,” declaring that he “was never a proper historian” but a “charlatan.”

* * *

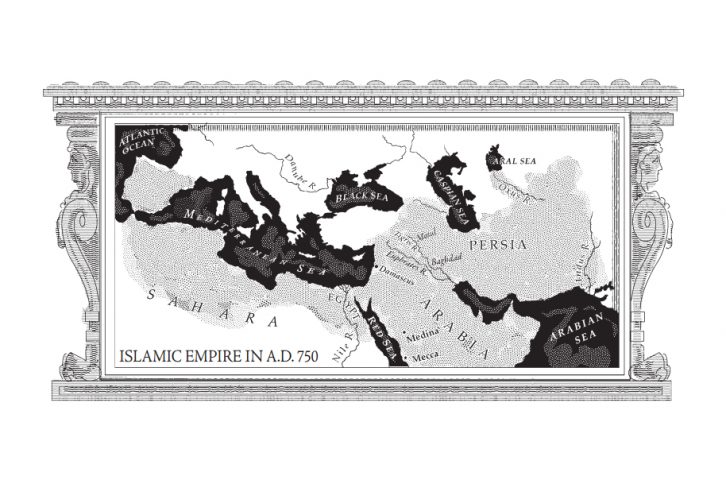

With its meticulous scholarship, Morris’s latest book refutes that charge. The story he tells hinges on three points. The first is that from the Arabs’ perspective the war of 1948 was not merely a territorial dispute, but a battlefront in the struggle between Islam and the West. Well before 1948, Arabs both inside and outside Palestine came to see the Jewish community there not only as an infidel presence in the heart of the Middle East, but as a beachhead of Western imperialism, embodying all the sins they imputed to the West. (The same view, two decades later, informed the Palestine Liberation Organization Covenant, which accused Israel of being “a geographic base for world imperialism placed strategically in the midst of the Arab homeland.”)

Accordingly, Morris paints the backdrop to the war by drawing from the palette of the jihadi rhetoric that preceded it. Imams across the Arab world, he says, alluded to the hadith (oral tradition) which teaches that “the day of resurrection does not come until Muslims fight against Jews, until the Jews hide behind trees and stones, and until the trees and stones shout out, ‘O Muslim, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.'” Undeterred by the fact that in 12 centuries of Muslim rule Palestine had never been treated as a distinct political territory by its rulers, they now pressed the Crusader analogy into service, invoking Saladin’s liberation of Palestine from the Christians.

As early as 1899, the mufti of Jerusalem proposed that all Jews who had come after 1891, the “new Crusaders,” be expelled or harassed into emigrating. In 1920, the pan-Arabist Awni Abdel Hadi vowed to fight “until Palestine is either placed under a free Arab government or becomes a graveyard for all the Jews in the country.” In 1929, that kind of rhetoric bore fruit: rioting Arabs killed about 130 Jews—a massacre that would be repeated during the Arab revolt of 1936-39.

As war loomed nearer, the belligerent rhetoric intensified. In 1946, a Baghdad newspaper called on Arabs to “annihilate all European Jews in Palestine.” “We will sweep them into the sea,” Arab League Secretary-General ‘Abd al-Rahman Azzam announced just before the invasion. The mufti of Egypt proclaimed jihad in Palestine as the duty of all Muslims, and King Abdullah of Jordan pledged to rescue Islamic holy sites.

Morris’s portrait of the Arab politics of hatred brings us to the second point that gives his narrative its inexorable motion: Arab rejectionism. In 1937, after governing Palestine since the end of the First World War, Britain convened the Peel Commission, which noted “the general beneficent effect of Jewish immigration on Arab welfare,” and recommended a partition of Palestine, granting Jews 20%, and Arabs more than 70%. Arab leaders rejected the proposal, insisting on all of Palestine. So too with Britain’s 1939 White Paper, which severely curtailed Jewish immigration, and promised Palestinian statehood within ten years. The Arabs demanded instead immediate independence and complete cessation of Jewish immigration.

In early 1947, the British had at last had enough, and resolved to withdraw their 100,000 troops and officials. This prompted United Nations Resolution 181, which once more proposed partition, with Jerusalem and Bethlehem under international control. Although Zionist leaders welcomed the new proposal, the Arab leaders opposed it, and threatened war should the resolution pass.

When on November 29, 1947, two-thirds of the General Assembly voted to approve partition, and thereby a Jewish state, the Arab delegations declared the resolution invalid. In response, anti-Jewish mobs took to the streets in Cairo, Damascus, and Bahrain. Seventy-five Jews were killed in pogroms in Aden, Yemen. Ten synagogues were torched in Aleppo, Syria. The Jews of Palestine, on the other hand, listened in ecstasy to the broadcast from Flushing Meadows. In his diary, Ben-Gurion wrote: “I looked at them so happy dancing and I could only think that they were all going to war.”

* * *

Circumstances proved Ben-Gurion right, though perhaps sooner than he expected. The war that broke out the next day unfolded in two phases. The first stage, lasting from November 30, 1947, to May 14, 1948, amounted to a civil war marked not by pitched battles but by small-scale guerrilla fighting that pitted Palestine’s 630,000 Jews against its 1.3 million Arabs.

When the fighting began, Palestine’s Jews could field two or three tanks, no combat aircraft, and almost no artillery. Yet although outmanned and outgunned, their fledgling army—many of its soldiers survivors of the Holocaust—fought fiercely. During the British Mandate, they had raised a 35,000-member-strong militia, the Haganah, which evolved into the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in June 1948. With the aid of the Palmach, its commando strike force (including the young Yitzhak Rabin), the Haganah defended Jewish communities, freed illegal Jewish immigrants from British prisons, blew up railway tracks and bridges, and ran secret arms factories. “It must be emphasized,” a Haganah directive declared, “that our aim is defense and not worsening the relations with that part of the Arab community that wants peace with us.” The Haganah competed with two more militant underground paramilitary groups, both condemned by the mainstream Zionists: Ezel, the military arm of the Revisionist party, with its 2,000-3,000 members under the command of Menachem Begin; and the Lechi (“the Stern gang”), a tiny group of fewer than 500 fighters.

In this first stage of the war, the Haganah battled local militias and the Arab Liberation Army (ALA), comprising volunteers from Palestine, Syria, and Iraq who were trained in Syria and commanded by the Iraqi general Ismail Safwat. The ALA’s symbol was a dagger dripping with blood, thrust into a Star of David. Aided by the likes of Fawzi al-Kutub, who learned bomb-making from the Nazi SS during World War II, the Arabs ambushed Jewish transports, attacked civilians, and assaulted Jewish quarters of cities throughout the country.

As Morris shows, early ALA successes caused a sense of despair to grip the Jewish community, especially in besieged Jerusalem. The first victories also impeded international support for Jewish statehood. Secretary of State George Marshall, for instance, reportedly said that the U.S. may have erred in supporting partition. Warren Austin, the American representative to the U.N., delivered an anti-partition speech at the Security Council.

Desperate to persuade the world of the viability of a future Jewish state, the Haganah shifted to an offensive stance; it started acting less like a ragtag underground militia and more like a disciplined army. As winter gave way to spring, the Haganah secured roads—especially on the western approach to Jerusalem—took villages which Arab militias had used as forward bases, and conquered Arab neighborhoods in Haifa, Tiberias, Jaffa, and West Jerusalem.

On May 14, after five and a half months of guerrilla fighting, High Commissioner Alan Cunningham left Jerusalem, bringing the British Mandate to its formal close. That afternoon, Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of the state of Israel. Minutes later, President Harry Truman granted de facto recognition to the new country.

The second, full-scale stage of the war began the next day. Some 20,000 combat troops—Egyptians, Syrians, Iraqis, and Arab Legionnaires from Jordan (led by experienced British officers)—poured into Israel, bent on strangling the state at its birth. On the one hand, the invaders enjoyed the initiative, the high ground, disproportionate economic resources, and overwhelming advantages in heavy weapons and firepower. (An August 1947 CIA report had predicted that if war broke out, the Arab forces would triumph.)

On the other hand, the Arab armies were hampered by incompetence, inadequate training, and disunity. Their war plan, Morris writes, amounted to nothing more than a “multilateral land grab” on the part of Arab leaders who gave no thought to Palestinian Arab aspirations, and assigned them no role in the invasion. Jordan’s King Abdullah, for one, had no interest in a Palestinian state on his doorstep.

In the next few weeks, more Arab brigades rushed to battle. Jordanian troops took the West Bank unopposed, beat back Israeli attempts to take Latrun (which controlled access to Jerusalem), indiscriminately shelled West Jerusalem, and captured the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. (When Israel recaptured the Old City from Jordan in 1967, all but one of the quarter’s dozens of synagogues were found destroyed.) The Egyptians began their campaign with air raids on Tel Aviv (including an attack on the central bus station that killed 42 civilians). But the momentum of their ground assault from the south was halted by settlements like Kibbutz Nirim—where 45 Haganah defenders, armed only with light weapons, staved off an assault by nearly 500 infantry backed by artillery and armor—and Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, named after Mordechai Anielewicz, hero of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. The Egyptians were eventually halted 18 miles short of Tel Aviv. The Iraqi force, meanwhile, the largest in Palestine, took Samaria, and routed the Jewish opposition in Jenin. (The Syrians fared worse: they thrust south of the Sea of Galilee, but were defeated so badly that the Syrian defense minister and chief of staff resigned within days.)

In mid-June, after a month of all-out fighting, a truce brokered by Swedish aristocrat Count Folke Bernadotte, the U.N.’s special mediator, came into effect. Two weeks later, the Israelis agreed to a month-long extension of the truce; the Arab League unanimously rejected it. When fighting resumed in July, it became clear the IDF had taken better advantage of the respite. “We spent the [truce] days as though we were in our barracks in Cairo,” an Egyptian officer named Gamal Abdel Nasser reported. “Our laughter filled the trenches.” Ten days later, a second truce halted hostilities until October.

The war ended in armistice, not in peace. Beginning in October, the IDF won decisive victories over the Egyptian forces in the south, chasing them out of all Palestine except the Gaza Strip. In the end, it added some 2,000 square miles to the 6,000 allocated by the U.N. Partition Plan. To save its army, Cairo signed an armistice in February. Jordan and Syria soon followed. These agreements would govern Israel’s borders until the 1967 Six-Day War. In the 1948 war’s aftermath, the defeated Arab leaders were not merely vilified. Egyptian prime minister Nuqrashi and Jordan’s King Abdullah were assassinated, and King Farouk was overthrown.

* * *

But a far more devastating result of the war, and the third hinge of Morris’s detailed account of it, remains the most contentious today: the 700,000 Palestinian refugees it displaced. The Palestinians’ flight began on the first day of the war, in November 1947; Morris estimates that during the civil-war stage 75,000 to 100,000 fled or were displaced. The first to flee were Arab notables, who escaped to Beirut, Damascus, and Amman; the Palestinians were deserted by their own elites. (Morris also discusses the other refugee problem: the 600,000 Jews expelled from Arab countries after the war began.)

The largest wave of refugees, however, took flight between April and June 1948. They fled for fear of getting caught up in the fighting, or of living under Jewish rule, or because of the soaring prices and unemployment brought about by the war. Others feared fellow Arabs who considered traitorous anyone who accepted Jewish sovereignty. Others were in effect driven away by their own leaders, or by the promises on Arab radio that residents could return home as victors after the imminent invasion by Arab countries.

In still other cases, Israeli soldiers, worried about a fifth column, encouraged Palestinians to flee, or expelled them. They razed some villages to prevent Arab forces from using them. But the Israeli policy was inconsistent and ad hoc. In Lydda and Ramla, the IDF expelled 50,000 residents (under orders issued by Rabin). In Isdud and Khirbet Khisas, the IDF ordered inhabitants who had not already fled to leave. At Majdal, by contrast, the IDF encouraged the villagers to stay, and even asked those who had already left to come back. In Haifa, Mayor Shabtai Levy pled with his city’s Arabs to stay. In Acre, many Arab residents did remain, and became Israeli citizens. The Galilee was left with substantial Arab populations. (Today, 20% of Israel’s citizens are Arabs.)

Morris doesn’t shrink from describing Israeli crimes—the looting of Arab houses; the execution of dozens in the village of Dawayima; massacres in the villages of Hule and Saliha along the Lebanon border; the atrocities committed in April 1948 by Ezel and Lechi fighters in the village of Deir Yassin, which included shooting unarmed prisoners.

Nor, for that matter, does Morris gloss over Arab massacres of Jews. He describes the cruel deaths of the inhabitants of the Etzion Bloc, south of Jerusalem, at the hands of the Arab Legionnaires to whom they had surrendered. And he tells how in revenge for Deir Yassin, Arabs ambushed a convoy of Jewish doctors, nurses, students, and academics on their way to Hebrew University, burning them alive. Seventy-eight died.

But Morris suggests that Arabs simply had fewer opportunities to commit atrocities; while Israelis captured hundreds of Arab villages and towns over the war’s course, the Arabs took fewer than a dozen Israeli settlements. Each of those, however, was destroyed. More to the point, Morris rejects the notion that the Haganah had a master plan for the expulsion of the country’s Arabs.

On the contrary, Zionist leaders took for granted the full equality of the Arab minority in the future Jewish state. In a letter to his son ten years before the war, Ben-Gurion wrote: “We do not wish and do not need to expel Arabs and take their place. All our aspiration is built on the assumption—proven throughout our activity—that there is enough room for ourselves and the Arabs in Palestine.” Ten years later, he declared hopefully:

If the Arab citizen will feel at home in our state…if the state will help him in a truthful and dedicated way to reach the economic, social, and cultural level of the Jewish community, then Arab distrust will accordingly subside and a bridge will be built to a Semitic, Jewish-Arab alliance.

“By contrast,” Morris concludes, “expulsionist thinking and, where it became possible, behavior, characterized the mainstream of the Palestinian national movement since its inception.”

Due to the availability of copious Israeli archival materials and the paucity of comparable Arab sources, Morris’s book suffers an inevitable foreshortening of perspective. It takes us inside Israeli cabinet meetings, for instance, but cannot shed much light on internal Arab deliberations. On the whole, however, 1948 is dispassionate in its tone, meticulous in its research, patient in its pace, and comprehensive in its scope. In presenting the first Arab-Israeli war as a culmination of Arab resistance to the Zionist enterprise, and in placing that war convincingly in the context of the still raging confrontation between Islamism and the West, Benny Morris’s history furnishes a compelling view of the origins of a conflict still very much with us. In ably following the thread of Arab rejectionism that wends its tragic way to the present, and in forcefully demonstrating that the Palestinian refugee problem was in large part created by a war the Arabs had initiated and lost, this book also offers an eloquent recovery of some political truths about the Middle East that have grown lamentably obscure.