There cannot a greater Judgment befal a Country than such a dreadful Spirit of Division as rends a Government into two distinct People, and makes them greater Strangers and more averse to one another, than if they were actually two different Nations…. A furious Party Spirit, when it rages in its full Violence, exerts itself in Civil War and Bloodshed; and when it is under its greatest Restraints naturally breaks out in Falsehood, Detraction, Calumny, and a partial Administration of Justice. In a Word, it fills a Nation with Spleen and Rancour, and extinguishes all the Seeds of Good-Nature, Compassion, and Humanity.

—Joseph Addison,

the Spectator, July 24, 1711

I don’t find the word “hyperpartisanship” in any dictionary. It’s not in the Oxford English Dictionary (last updated in 2015) or even in the online Merriam-Webster Unabridged, usually nimbler with neologisms. But dictionaries, as usual, lag behind usage. A Nexis-Uni search finds the earliest attested use of the term in 1992, and an explosion in its use after 2000. Given the state of U.S. politics since 2000 that is not surprising. Yet one is tempted also to correlate the monstrous coinage with the decline in knowledge of languages other than English among journalists and public intellectuals. The word is technically a barbarism, half Greek and half Italian. “Hyper-” is a Greek prefix. “Partisan” is from partigiano, first attested in the 15th century, via the French partisan, first attested in the 17th; both derive from partes, the Latin for political factions. “Superpartisanship” would have been a less barbarous coinage but also less pretentious, and therefore less attractive to the half-educated. “Hyperstasis” would be a sound coinage but incomprehensible as well as pretentious. But let there be barbarous names for barbarous things.

Diagnosing the Disease

We historians know that new words are signals of wider changes in the world of thought. Something is going on in the culture and new words are needed to describe it. Angelo Codevilla’s apt phrase “the Cold Civil War,” only recently applied to U.S. politics, points in the same direction. Partisanship is normal; hyperpartisanship is not. We’ve had partisanship from the very beginning of our republic. The U.S. Constitution was designed in part to restrain its destructive tendencies, though the founders knew that the republican form of government could not subsist without some degree of partisanship. They well understood the lessons of Western political thought. The writers of The Federalist well knew that the “spirit of party” had only been stilled for a moment by the unified sense of purpose that, driven by necessity, had brought to life the American Constitution. Aristotle in antiquity already showed that partisanship is inseparable from free political life. You can have monarchy, a single decision-maker, or you can have power shared among the few or the many. If power is shared, you are going to have parties, groups of men struggling to decide who gets to decide for everyone. The challenge for statesmen is to limit partisan passions or channel them in benign ways.

Partisanship is even more inescapable in modern democratic republics. What matters is how parties and partisans behave. In her 2008 study On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship, the Harvard political theorist Nancy Rosenblum defended political partisanship against its critics. She argued that partisanship should be accepted and even celebrated as a good thing, a necessary condition of democratic pluralism. Publicly recognized electoral parties are desirable if democratic politics are going to represent multiple points of view and be accountable. Parties propose policies, and voters get to decide which policies they want. If parties fail to deliver, they can be voted out at the next election. When democratic partisanship is working well, administrations change but the system remains stable. Partisanship is a feature, not a bug, of successful democracies. “Anti-partyism,” on the other hand, is typically a product of what the late Kenneth Minogue called “one-right-order” societies, premodern societies like imperial China or the medieval West with shared, holistic visions of public order. Such societies inevitably read all partisanship as immoral and seditious. Alternatively, anti-partyism springs from a belief, like that of the early Progressives, that political struggle is an outdated relic of the past and should be replaced by the rule of scientific experts.

Hyperpartisanship, however, differs from the ordinary partisan politics of democracies. It is something abnormal, a political disease. History warns us that extremes of partisanship are the antechamber to tyranny. Just think of the late Roman republic, the demise of the popular commune in medieval Italy, the career of Savonarola in Renaissance Florence, the “Protectorate” of Oliver Cromwell that brought an end to the English civil wars, or the rise of Napoleon. A healthy democracy requires a degree of partisanship, a loyal opposition. Hyperpartisanship makes republics—lawful power-sharing arrangements directed to the common good—ungovernable. It destroys their legitimacy and ultimately forces a change of regime.

Hyperpartisanship can be distinguished from normal democratic partisanship by certain features. Hyperpartisans live in bubbles, cut off from rival claimants to public authority by mutual incomprehension and mutual revulsion. They are dogmatic, intolerant, unable to sympathize with alien points of view. Opponents are demonized, their reputations destroyed by all means possible. Democratic deliberation becomes impossible and political deal-making—the normal business of interest-group politics in pluralist societies—is despised as an intolerable violation of principle. Politics turns into a battle between non-negotiable demands. Compromise is impossible; the enemy must be crushed.

When the results of democratic procedures such as elections go against hyperpartisans, they will question their legitimacy. Instead of transactional politics, hyperpartisans engage in “resistance,” a word linked historically to the struggle of partisans against fascists in World War II. Anti-fascist partisans see any government under the control of their opponents as an enemy occupation. They themselves constitute the true government, a government in exile. Members of resistance groups don’t accept electoral results but engage in coups and conspiracies and encourage violence. They debauch justice, corrupt journalism, and instrumentalize academic research in their scramble for power. History turns into partisan storytelling—no longer critical, fair, or conscious of anachronism. The result is that journalism, scientific research, court proceedings, and historical writing are distrusted by those outside the hyperpartisan bubble that produces them. Rational means for settling disputes between contrasting beliefs become discredited. Hyperpartisanship thus blocks every avenue to settling political disputes in a harmonious way, which is why, sooner or later, it leads to tyranny. The pattern of tyrants since the time of Pisistratus, the 6th-century-B.C. tyrant of Athens, is to crush partisanship—and with it, constitutional governance—using military force.

Stunted Outlook

The lineaments of hyperpartisanship are all too easily recognizable by those who live in periods such as ours. Much less obvious is the damage done to conscience and to powers of moral reasoning. Believing themselves actuated by the purest virtue and benevolence, hyperpartisans fail to perceive the injustice of their own actions. They become blind to the evil done by their own side and refuse to see the good done by the other. Their blindness stunts their faculties of moral analysis and judgment. They become morally desensitized. The hyperpartisan is always excusing evils done by her own party, using a utilitarian calculus to suppress natural responses of shame and guilt. The best moral training, as Aristotle taught, teaches the young to seek honor and feel shame about the right things. But when evil acts are constantly being done to advance a cause—lying, committing fraud, dehumanizing opponents, condoning hate and violence—a kind of moral numbness results. The hyperpartisan is surrounded by people who approve of her actions, and any internal voice of conscience she might possess is drowned out by the applause of her fellow partisans. As Voltaire observed, “People are never ashamed of what they do in groups.” Groups of partisans are too ready to overlook the poor character of people allied to their cause. The effect is to discount the need for good character in politics. Hyperpartisanship destroys not only civility but common standards of right and wrong. The hyperpartisan loses all appreciation for moral beauty—what the Greeks called to kalon, the good act that is beautiful because it is good. Seneca advised the angry man to look in the mirror and see how ugly his face becomes when angry. Hyperpartisans never look in the mirror. They are unaware of their own moral ugliness, how the rest of us see them.

Moral maturity requires engagement with people who think differently. The person who aspires to excellence of mind and character must make an effort to understand why other people think differently about ethical and political questions. The struggle to form a good character gives the morally mature person self-awareness, a proper pride and a proper humility. The self-aware man will realize that another person may have experiences or knowledge that make that person’s beliefs, however different from his own, still worthy of respect. He knows that at the root of all serious disagreements are things of value to which each party clings, often for very good reasons. The key to civil compromise is the ability to recognize the value of what others value. To lack that ability is to lack humanity. But the hyperpartisan dismisses as stupid or evil persons who don’t share her agendas, and takes as worthless the things they value. She substitutes name-calling for moral reasoning. People who don’t agree with her are racists, sexists, fascists, or white supremacists. Name-calling takes the place of moral reasoning and face-to-face engagement with persons whose opinions may contain elements worthy of respect and serious debate. Hyperpartisanship gives you a shallow, stunted moral outlook; you passively absorb the moral strengths and weaknesses of the people around you.

It also makes you stupid. Hyperpartisans cannot understand why their values are not universally shared. Unwilling to understand or consider analytically opposing points of view, they come to believe that the triumph of their own unquestioned and unquestionable beliefs demands the forcible suppression of the rival beliefs they abhor. Incapable of rigorous moral reasoning, their worldview becomes populated with inconsistencies, contradictions, and absurdities. To anaesthetize the cognitive dissonance in their minds, they invent or embrace an ideology, like an oyster surrounding an irritant with mother-of-pearl. Ideologies are not philosophies, and ideologists, the manufacturers of ideologies, are not philosophers. They are militants who exert discipline over their cadres, and their job is to erase doubt. Doubts arise from nuance, exceptions, reservations, qualifications, counter-cases, and any empirical data which might undermine the ideologist’s narrative. They have to be discouraged or excluded, and practical reason along with them.

A Mind That Is Not Free

Ideology is therefore the enemy of reason. By definition an ideology is a system of ideas accepted for reasons other than the intrinsic validity of its claims. One embraces it because one finds it “comfortable”; it suits one’s prejudices, socioeconomic status, gender, race, or tribe. It constitutes a ready-made, holistic worldview, resistant to empirical refutation, that justifies groups in advancing their bid for power over others. Embracing a philosophy, on the other hand, is by definition the act of an individual, a free mind. To stick to a philosophical truth at odds with one’s own interests and background can be supremely uncomfortable. It requires moral strength and a deep commitment to reason. It disables partisanship, but also makes it harder for the philosopher to defend his interests in a political way.

The more tightly you embrace an ideology, the more you cease to be a free moral being. Serious thinkers, people who have coherent philosophical opinions of their own, do not receive them unexamined from groups of persons with an agenda. They read philosophers and scientists, and decide which claims or arguments they can accept. They do this by struggling with the thought of great minds, reconciling it (or not) with their own positions and their own experience and convictions. They know how to restate the opinions they are being expected to embrace as arguments, and to ask whether the premises are true and whether the conclusions follow from the premises. They also study history. They want to know how the beliefs they are tempted to embrace have worked out in practice in the past. They think through the consequences of holding beliefs and in the process find out whether their beliefs align with prudence or practical wisdom, phronesis. They tend to be eclectic. Even if they accept for a while some maître à penser or teacher, that person ultimately shows them how to think, not what to think. He sets them free to choose the true and the good.

Partisan ideologues do the opposite. Their mental processes are tribal. Their minds repose in their ideologies like a child in the arms of its mother. They resist being challenged. The manufacturers of ideology bid them show their loyalty by believing three impossible things before breakfast, and they will believe six. They are incapable of the independence of mind and strong character needed for philosophy, but that does not make them prepared to engage in a healthy democratic politics instead. The hyperpartisan has contempt for the type of sound politics in which citizens confront the beliefs and needs of others and find compromises or solutions that respect the common good. They are unaware of, or deny, the selfish interests driving their own embrace of political ideals, and so are incapable of taking part in political transactions.

Hyperpartisan logic demands a rigorous application of the law of the excluded middle. All immigrants must be allowed in, or all kept out. Immigrants are either holy victims it is our duty to revere, or the criminal refuse of failed societies. Enforcement of immigration law is either genocide or the sacrament of our nationhood. Hyperpartisans don’t like the study of history either, since historical knowledge is the foundation of practical wisdom and the enemy of dogmatic political prescriptions. Politics for hyperpartisans is rather a conspiracy against the unenlightened, those who fail to share their vision for the future. They realize that an honest search for solutions to real political problems might force them to compromise with their dogmas. Thus the hyperpartisan mode of politics atrophies and enchains the intellect. Hyperpartisans cook up brilliant schemes to win power, but are incapable of reflecting freely on the right ends of power. Their reasoning is purely instrumental; they are strangers to the contemplative life and lack any vision of the good, for Plato the highest achievement of human rationality.

Changing Hands

Is there a way out for polities infected by the disease of hyperpartisanship? History, sadly, does not give us a great deal of encouragement. The usual way that polities exit from periods of hyperpartisanship is via war, revolution, or tyranny. Any student of history can immediately remember examples. The worst period of hyperpartisanship in classical Athens led to oligarchic coups and defeat in the Peloponnesian War; the hyperpartisan divisions of late republican Rome led to the autocracy of the Caesars; most of the popular communes of medieval Italy were driven by extreme factionalism into the arms of tyrants; the bitter ideological polarization of the late Romanov period was shut down by the Soviet totalitarian state; the collapse of the liberal Weimar Republic into violent partisan struggle led to Hitler’s dictatorship. Yet there are also cases, less familiar, where hyperpartisan passions subsided and normal, transactional politics were resumed in their place. How and why this happens deserves much more study. A historian may think of the reforms of Cleisthenes in Athens after the Pisistratids, Florence after the Ciompi uprising of 1378, England after the defeat of the Stuart cause, or France after the Paris Commune of 1871. In all these cases, near breakdown of the social and political order forced political elites to find more civil ways to manage partisan differences. Indeed, in the case of democratic Athens, Renaissance Florence, the early British empire, and the French Third Republic, more harmonious forms of civil order led to long periods of relative stability and flourishing.

The key to success in all these cases seems to have been the discovery of modes of balancing interests and sharing power, thus creating incentives for cooperation while reducing ideological passions. In particular, statesmen in these polities created institutions and practices that preserve what Italians call alternanza: the ability for power to change hands via strictly political means. (In Italy they have a lot of experience changing governments.) The principle of alternanza requires civil procedures and shared norms that prevent the political party in power from turning the organs of government into a fortress protecting its own position—from trying to remain permanently in power. A political party in power will not abuse public authority to weaken its opponents out of power. It will not use its powers to booby-trap the state so that opposing parties, when they come to power, are unable to implement their policies. Balancing interests and alternanza require that such partisan acts are recognized and publicly stigmatized as a form of political corruption. They must be seen to be every bit as corrupt as enriching oneself in public office or sexually exploiting subordinates—what Americans today typically understand as corruption. The integrity of law and constitutional government must be acknowledged as a thing higher than the transient goals of mere politics. Unstated is a negative, political version of the Golden Rule: don’t do unto others now lest they do the same unto you later. That is the principle that underlay the Senate’s filibuster rules, until recently.

The principles of balance and alternanza carry lessons for modern American politics. It is notorious that for more than a generation the two principal parties, at the federal level at least, have been so finely balanced in their political support that victory in national elections can hang on voter swings of a few percentage points. The balance of political power in the judiciary is also now more equal than in previous generations. Pundits often take this rough equality in electoral and judicial power to be a cause of hyperpartisanship, but in practice it does as much or more to limit it, since each party out of power hopes it will soon be back in power. The defeated party, or at least its most pragmatic members, do not want the equipment of government to be damaged or its authority rendered illegitimate when it takes over the reins again. All this was anticipated to an extent by the founders, who designed the Constitution to calm partisan storms, contain sectional rivalries, and prevent factions—even majority factions—from damaging the stability of federal institutions.

Leviathan’s Rise

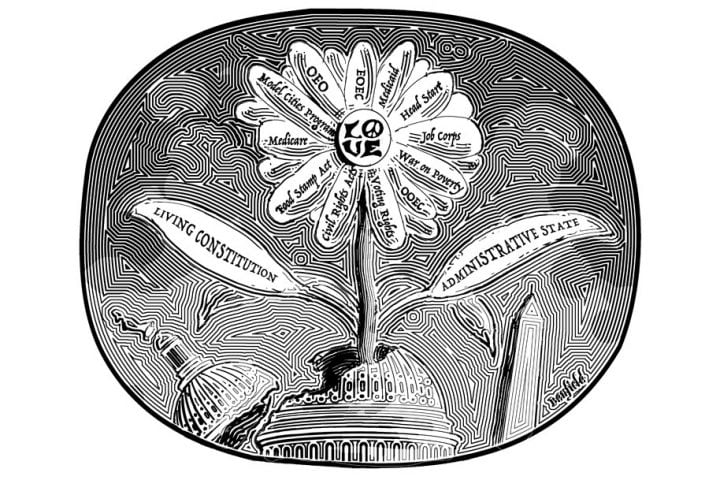

What the founders didn’t anticipate, of course, was the hypertrophy of the federal government in modern times, and the aggrandizement of its powers at the expense of state governments and private freedoms. This is surely the principal cause of hyperpartisanship today. The more the federal government gets control over economic activity and the natural environment, the more it restricts private freedoms—especially the free exercise of religion—and the more slyly it tries to nudge us into compliance with alien social norms, the more grounds will exist for partisan grievance, and the more fiercely partisans on both sides will fight to proselytize or preserve whatever gospel truths they hold. Politics inevitably becomes less calmly transactional and more like religious civil war. The obvious solution to this problem, reducing the size and scope of the federal government, however attractive to conservatives, does not seem destined to occur before the Greek kalends—or (more likely) before complete financial collapse. If the latter happens we shall have even bigger troubles than hyperpartisanship. Pragmatic solutions to hyperpartisanship in the short term, while Great Leviathan rises in his glory, must be found elsewhere.

The new kind of hyperpartisan political world, where every aspect of one’s life can be touched by the party in power, was not anticipated by the founders. They took steps to guarantee alternanza in politics, but politics today is about far more than who holds elective office and distributes a few crumbs of government patronage. Though the major political parties in federal elections are roughly equal in electoral power, in other arenas where political matters are contested they are vastly unequal.

There are two battlefields in particular where conservatives are mightily outgunned by progressives: in the administrative state and in educational and cultural institutions. The experience of the current presidency has made it clearer than ever that the administrative state is staffed by individuals of a deeply partisan bent who are often in a position to, and often inclined to, continue and preserve policies at odds with those of elected officials. As public-choice theory has long argued, a large bureaucracy can never be neutral between interests but is itself an interest, and its chief interest is to become ever larger and more powerful. If a political party opposes its aggrandizement, the bureaucracy will oppose that party. In addition, it has been obvious for decades that progressives are overwhelmingly dominant in the public realms of culture: K-12 education, teaching colleges, universities, journalism, charitable foundations, the arts, cinema, and popular music. In recent times even some large corporations, with their vast powers of patronage and the siren voices of their advertising, have joined the cultural battalions arrayed against conservatives. The incentives that once existed in capitalist society for companies to refrain from ideological messaging have weakened. No doubt this is another effect of the hypertrophy of state power and the consequent embrace of statism by social elites (and would-be social elites).

My point is not that this situation is deplorable (though it is), but that the imbalance in administrative and cultural power between progressives and non-progressives is among the major preconditions that allow hyperpartisanship to flourish. If there is to be any hope of restoring healthy, democratic parties in American political life, the existing correlation of forces will have to come back into some kind of balance, enough to force the dominant and the subaltern parties in government bureaucracies and in cultural institutions to treat the other party with respect and to negotiate with reason and humanity instead of contempt and mutual aggression. To put this in more personal terms, if all your colleagues in a non-political institution are progressive (or political radicals of any stripe), the temptation to politicize the institution, to use its power to achieve political goals unrelated to its formal purpose, becomes irresistible. An institution is far more likely to remain politically neutral, supra partes, when the political commitments of its leadership and staff represent a broad range of beliefs. It is also the case that institutions with specific functions, such as education, entertainment, or producing goods and services, best perform those functions when they are not being weaponized for political ends. But that is a separate issue.

I won’t comment here on the project of taming the administrative state and forcing it to be more responsive to political leadership. It is surely a potent cause of hyperpartisanship when elections fail to produce results and the promises of political leaders prove fraudulent or inoperative, frustrated by corruption or the ideological resistance of bureaucracies. Conventional wisdom preaches that ineffective government breeds apathy, but the opposite is more often the case. The failure of political movements to produce the desired changes, even after they have been victorious in elections, more often produces the symptoms of hyperpartisanship: alienation, anger, paranoia, and conspiracy theories. Stark demonstrations that political power is unaccountable to the people, such as the open sabotage of Brexit lately attempted in the British Parliament, produce toxic levels of partisanship. In this country, the obvious countermeasure—making it easier to fire or discipline civil servants for insubordination—has often been proposed, and public-choice theorists and conservative legal scholars have advanced various other remedies. Conservative activists have only recently addressed the issue of how to train public servants so that they do not automatically embrace statist and progressive values. Nevertheless, ideological balance and hence the restoration of an ethic of non-partisanship among administrators in their serried ranks will be a long time in coming.

In the remainder of this essay I will focus instead on the imbalance of politico-cultural power in our polity—a subject that has been far less productive of theoretical reflection among conservatives—and outline some strategies for overcoming it.

Achieving a Balance

The mere thought of conservatives entering into a discussion of increasing their cultural power in America generates a pleasing frisson of irony, indeed multiple ironies. A first irony is that such a discussion requires some minimum of theoretical language. As it happens, the most sophisticated theoretical languages for discussing issues of cultural dominance were created by Marxists during the 1930s: by Antonio Gramsci, a founder of the Italian Communist Party; by the Frankfurt School with its Critical Theory; and by Mao Zedong, who put his theories into action in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution. These languages have been elaborated and refined by later Marxists in the course of the last half-century, above all in the flourishing field of post-colonial studies (known as “poco theory” in academic slang). Activists on the Left have been following the praxis outlined by these Marxist theorists for decades.

A second irony, more delicious than the first, is that in any realistic analysis of cultural power in America today it will be the progressives who play the part of the colonial oppressors. Like pukka sahibs swaggering around their colonial tea plantations, progressive administrators strive to stamp out the indigenous culture of “whiteness” and subject the natives to the empire of wokeness. White is the new black and the new brown. It is the progressives in education, the media, the arts, the woke corporation, and Foundationland who use their economic and political power to deprive “subaltern” deplorables of agency, silence their voices, and deny them the resources to foster independent thought. They thus commit constant acts of “epistemic violence,” in Michel Foucault’s expression, similar to those so harshly condemned by poco theorists. Progressive cultural monitors seek to place conservative ways of thought and speaking outside the norms of the “hegemonic discourse,” whose authority is reinforced by speech codes, Title IX coordinators, bias response teams, and other apparatus for stigmatizing and excluding those who fail to conform to the dominant ideology.

University and corporate “diversity and inclusion” bureaucracies play the part of colonial police forces, plying their truncheons on any natives who defy the hegemon, and rewarding spies and collaborators. They commit the colonialist crime of presenting humanity as divided into separate and unequal cultures, labelling subalterns with reductionist terms such as “racist,” “sexist,” and “white supremacist,” thus “essentializing” and dehumanizing them. They also characterize them as “backward,” “stagnant,” and “primitive,” adopting the same terms of disapprobation used by colonial powers to describe the native and indigenous cultures they conquered and erased. They use their power in the world of fashion and glamour to form systems of social exclusion that make the language, dress, and behavior of conservatives barriers to upward mobility. Conservatives who wish to succeed in progressive institutions are compelled to don masks designed by their masters, an act which, as Frantz Fanon wrote of Algerian blacks, forces upon them a servile mentality and deprives them of authentic agency, even sanity. The dominant media image of non-progressives is reshaped by negative exclusions, “othering” them in a “discourse of difference.” This discourse is designed, as the radical cultural theorist Stuart Hall wrote of European orientalizing discourses, to cast the conservative as a moral, cultural, and intellectual inferior in need of ideological cleansing and reeducation.

A third irony arising from any conservative project of equalizing cultural power is this: that conservatives too can make use of the very strategies for fighting colonial oppression developed by Marxist theorists since Mao and Gramsci—at least up to a point. Indeed, conservatives already, and for a long time, have been using certain strategies that (presumably unconsciously) mimic the ones poco theorists have championed to protect native cultures “erased” by Western imperialists. Gramsci himself praised activists who set up “counter-hegemonic” institutions like labor unions, leftist book clubs, workers’ cooperatives, and newspapers that could counter the dominant ideology and build pockets of resistance to bourgeois cultural hegemony. This is what Gramsci called the “war of position.” By raising the consciousness of the proletariat, counter-hegemonic institutions led by “organic intellectuals”—intellectuals who represent excluded interests in capitalist society—could fight against the control of culture by “traditional intellectuals.” The latter structured intellectual discourse in such a way as to render impossible any criticism of capitalism or colonialism. Once counter-hegemonic forces had fought a war of position, they would have the power to begin a “war of maneuver,” the “long march through the institutions” as it was later called, which would destroy capitalist culture and replace it with revolutionary socialism.

The Red Army of radical progressives and the intersectional victim-elites they champion are now nearing the end of their long march and have established dominance over many Western cultural institutions. They have come close to succeeding where Mao failed. They have nearly completed a Cultural Revolution in the West, and have become the new traditional intellectuals, able to dictate cultural values. Conservatives in the most prestigious cultural institutions have gradually been pushed out or silenced, reduced to subaltern status. They have thus been forced to fight their own war of position, establishing parallel, “counter-hegemonic” institutions to preserve their native, organic culture. These include think tanks, law schools, academic programs and honors colleges, non-profits, prizes, lecture series, and centers, as well as media outlets such as radio and television networks, news magazines, journals, websites, and blogs.

Electoral Victories Aren’t Enough

Yet, as poco theorists might have warned them, there are limits to any counter-hegemonic war of position within a dominant culture. The dominant culture through its very dominance generates a glamour of power and prestige that is difficult to challenge. Progressives keep such tight control over who gets to be a Hollywood star or a pop music icon, for instance, that progressive politics now seem indissolubly wedded to the very idea of fame. Conservatives can only succeed in these fields of endeavor by concealing their politics. Actors and musicians know they can advance their careers only by outdoing each other in professions of wokeness. Conservatives can found all the prizes they want, but they are never going to have the cachet of the Nobel Peace Prize, the MacArthur “genius grants,” the Pulitzer Prizes, or the Academy Awards. Hillsdale College may offer a better education than Harvard, but that will not keep the ambitious young from accepting Harvard’s offer first. All power is conservative, and the power of prestige is no exception. Without political control of the most prestigious media outlets, journals and reviews, prize juries, hiring and promotion committees, conservative ideas can never effectively challenge the hegemony of the cultural Left. They won’t be able to alter the dominant consciousness (or “common sense” as poco theorists call it) of most citizens. As one critical theorist at New York University put it, “You may be able to seize a factory or storm a palace, but unless this material power is backed up by a culture that reinforces the notion that what you are doing is good and beautiful and just and possible, then any gains on the economic, military and political fronts are likely to be short-lived.”

Victory in electoral politics alone, in other words, isn’t enough. It is true that political victory ordinarily reinforces cultural prestige, and part of the furious reaction of progressives to the 2016 presidential election revealed their panic that the glamor of power might accrue to deplorables, just as Ronald Reagan brought a new cachet to classical liberalism in the 1980s. In the event, they needn’t have worried. Progressive cultural power has so increased since Reagan’s time that public service in the current administration is accounted a disgrace in the dominant culture. Public servants are spat upon, shot at, harassed, and driven from restaurants. Cultural hegemony means that the hegemons get to define what counts as good or evil and what counts as valuable goals for society. Being subaltern, like conservatives, libertarians, traditionalists, and non-progressives of all varieties today, means that your beliefs and your work are not only devalued and “cancelled,” they are regarded as outcroppings of ignorance, even positively evil, dark obstructions in the shining path climbing up toward the utopian future.

Hence the need for conservatives in the culture war to shift from a war of position to a war of maneuver. Some beginnings of a kind of countermarch or reverse march through the institutions are already visible. Thanks mostly to the Federalist Society, conservatives have had some success at repopulating the federal and state judiciaries with voices from outside the progressive “mainstream,” potentially turning that mainstream into just one of several tributaries flowing toward a more balanced judicial culture, and one, therefore, more oriented to the common good.

In the groves of academe, too, there are a few gardeners determined to prune back the weeds of authoritarian progressive groupthink. The American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA), a non-profit, has used its resources to prevent intolerant ideologues from hardening the academy’s arteries. The Heterodox Academy, a virtual community under the leadership of NYU’s Jonathan Haidt, has created “a collaborative of academic insiders” to combat “motivated reasoning, confirmation bias, and tribalism” in our increasingly hyperpartisan academic culture. By calling for “viewpoint diversity,” Haidt has cleverly followed the advice of Gramsci to use the values of traditional intellectuals against them, exposing the contradictions that seethe in the shallows beneath the slick surfaces of university brochures. How far this will succeed is another question. Haidt is an eminent social scientist and a brilliant communicator of transparent sincerity and good will, but his opponents, entrenched in “diversity and inclusion” bureaucracies, have little incentive to cooperate in undermining their own power. Their commitment to the life of the mind is minimal, but they have a great deal of commitment to keeping their jobs. Their own acquisition of power is recent enough that they are not likely to fall in line with any reverse march through the institutions or allow themselves to be turned into useful idiots. The professoriate on the whole is more open-minded, more collegial, and friendlier toward balanced debate. But so long as most professors sympathize with the progressive goals of woke administrators or are afraid to oppose them, so long as most university presidents remain profiles in cowardice, the “diversity and inclusion” establishment, despite its contradictions and intellectual shallowness, will be hard to undermine.

Tactics and Strategy

Just as in the war of position, in short, libertarians, conservatives (a.k.a. classical liberals), traditionalists, and other non-progressives—whom I’ll call LCTOs to give them acronymic status—have grave disadvantages when it comes to a war of maneuver. These are both tactical and strategic. One tactical disadvantage is simply that progressives enjoy engaging in political activism while LCTOs do not. Progressives, especially in power, have a way of swarming the opposition by the sheer number, range, and ambition of their policies, programs, petitions, initiatives, and causes. They are always on the march, and the prospect of solving all the world’s problems—by next week at the latest—fills them with joy and vigor. It is said that on the Upper West Side of New York the young can only reproduce after signing petitions. Progressives are also gregarious and form naturally into herds. LCTOs do not similarly aspire to dry every tear. They tend to be individualists and want to preserve the private. They have other things to do with their time. They think that most of humanity’s real problems at ground level are private problems, and must be solved by private individuals helping each other. Politics for them is like the lower bodily functions: necessary but unsightly, a duty to be discharged as quickly and discreetly as possible.

A second tactical disadvantage is that LCTOs are less comfortable with “dirty hands” than progressives. As individualists they value integrity of character and do not happily blend into communities of disciplined groupthink. The party is not their highest good. To be an LCTO in a progressive institution means to operate silently behind enemy lines, using codes and disguises, and this involves uncomfortable compromises for persons of settled character. As the progressive Left is more and more demanding the functional equivalent of loyalty oaths—requiring employees to undergo “diversity training” or sign statements of “community values” as a condition of employment—any reverse march through the institutions may soon have to begin with lies and the sacrifice of personal integrity. Jesuitical “mental reservations” and the distinction between suppressio veri and suggestio falsi may soon become relevant again, as during the early modern Wars of Religion, the longest and most intense period of hyperpartisanship in Western history.

LCTOs also suffer from one huge strategic disadvantage: the war of maneuver is one they should not want to win. To win it would defeat their larger purpose. It would just exchange victor for vanquished, and leave the disease of hyperpartisanship to rage unchecked. If we are serious about achieving balance and alternanza in our cultural life, we don’t want any party to “control the discourse” the way the progressive Left now does in most universities and cultural institutions. Hegemonic discourse enslaves minds, but the philosophical statesman wants minds to be free. A free mind is one that has freed itself; despite Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in the realm of intellect we cannot be forced to be free. To be sure, some of the freest minds have existed under the most tyrannical ideological regimes, as the single example of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is enough to show. Nevertheless, a healthy society will promote and defend the conditions for intellectual freedom. What the philosophical statesman wants are multiple voices, a free flow of information, and arguments whose conclusions have not already been dictated by political ideologies. We want a country with people who, like Socrates, are willing to follow the argument wherever it leads. Just as in democratic politics, laws and the constitution need to be elevated above the objectives of partisan politics, so in a democratic culture the truth must be privileged above any particular beliefs.

That is the main reason why LCTOs should want to fight a defensive war of maneuver, a limited war, and not seek unconditional surrender. The other reason why they should want parity and balance in cultural as well as in political life is because that is the only way to depoliticize the culture. The most basic question in politics is what should count as political, and LCTOs, unlike the Left, want less of our lives to be political. For us, the personal is emphatically not the political and should not be. But cultural balance is the way to achieve this, not conquest and destruction of partisan enemies. We don’t really want to turn Harvard and Hollywood into smoking ruins; we want their denizens to rediscover their true purposes and flourish as educators and artists. We don’t want to weaponize religion, science, and sport the way the Left does, or would like to. Those who have observed the Left’s long march through the institutions in recent decades will understand all too well how hyperpartisanship corrupts institutional values. But when a corporate board room or a college department meeting or a prize committee is not of one mind in politics—and is known to be not of one mind—when there is balance among political points of view, the scheming of political partisans to dominate will be far less successful. Organizations with non-political goals will be compelled to turn their attention to their actual jobs, making products that people want to buy, entertaining as many people as possible, gathering all the news that’s fit to print, or teaching the disciplines they are paid to teach. Human beings are herding animals and under normal circumstances shun conflict with other members of the herd. In a balanced, free culture where it is possible to express diverse beliefs, unless an organization or institution is specifically concerned with politics in the public realm, it will avoid occasions of political conflict.

Never Finally Defeated

Some will argue that a defensive war of maneuver, merely pushing enemies back to their natural borders, seeking to balance them, not defeat them, is an unrealistic strategy. Certain beliefs are too aggressive to be compatible with free cultural and intellectual life. They cannot be tolerated, only defeated. Marxism as a mode of thought, especially in its contemporary “cultural” form, is deeply unphilosophical. It no longer works by argument but by “recognition,” consciousness-raising, woking-up. It assumes there can be no common premises with persons inhabiting alien ideologies, which are by definition tools of oppression. There can only be conversion or unmasking of enemies, defeat and humiliation of incorrect thought. Contemporary Marxists argue by moral labeling and denunciation, which are not arguments. Life as critique means that there is no real possibility of solidarity beyond the party. Critical Theorists cannot compromise, they cannot participate peaceably in civil society on a basis of equality with other ways of thinking. Their style of politics does not permit of cost-benefit analyses or negotiation. For the Frankfurt School there is no state, there can be no state, even in a Utopian future, where there is no politics. Even death doesn’t put an end to politics since death only begins the struggle to control a person’s legacy.

For the Marxist Left, political struggle is the inescapable medium of all human life. Modern cultural Marxism, in short, is the opposite of Socratism. Antonio Gramsci is the anti-Socrates of the moderns. Cultural Marxism must therefore be defeated, according to some conservatives, before true freedom can emerge again in civil society. If our ultimate aim is to reverse the politicization of everything, we must start by erasing cultural Marxism. Écrasez l’infâme! If our purpose is to calm hyperpartisanship, we must defeat an ideology that seeks to turn every aspect of life, down to the choice of your favorite brand of ice cream, into a partisan issue. As students of Aristotle’s Politics know, to increase partisanship is part of the tyrant’s strategy of domination, and free men and women must oppose tyranny.

But again, the goal of the philosophical statesman cannot be the defeat of particular ideologies, but restoring pluralism in culture, bringing an end to the present woke-progressive monoculture. The philosophical statesman understands that the human proclivities underlying the progressive pursuit of dominance are permanent features of pluralist societies. They can be suppressed but never finally defeated. This is a principle that Niccolò Machiavelli well understood. He criticized Florentine popular statesmen who naïvely believed they could defeat the aristocrats and restore equality by banning specific noble families from politics. Machiavelli saw that the two fundamental political humors—those who wanted to dominate and those who wanted not to be dominated—would always exist in republican politics. If you exiled certain arrogant noblemen as incapable of participating in civil life, others would simply take their place. If you exiled all the nobles, a new elite of commoners would form itself into a new power-seeking humor. In the constitution he designed for the Medici in 1520 Machiavelli proposed a system of balancing the two humors so that each would have a permanent voice in government. In his view, the best and strongest republic was one whose “modes and orders” enabled, but also constrained within limits, the natural conflicts between the two humors.

So the philosophical statesman will understand that his goal is not to abolish one humor in politics but to balance it with the other. We should be laying out the lists as fairly as possible, not charging into the melee. If we start from the position that Francofurtum delendum est we are going to defeat our real purpose. A strategy of seeking total victory over cultural Marxism, in any case, gives it too much credit. It overlooks how intellectually feeble it already is. Cultural Marxism is able to flourish today precisely because of hyperpartisanship. It appears strong only because it is a weapon clasped in the fist of ideological tyranny. In a more pluralist culture, it would have to defend itself against critics who do not share its premises, and it would soon find itself at a serious disadvantage. Cultural Marxists are good at policing their own ranks for unorthodoxy and exposing the hidden power-relations that sustain (as they wrongly think) all non-Marxist structures of thought. They are not good at finding common premises with non-Marxists, and therefore at constructing arguments with universal validity. But in politics, constructing arguments with universal validity is what we call seeking the common good.

Cultural Marxists are also not good at being understood by laymen. Their jargon is rebarbative and easily mocked, ill concealing their poverty of thought. Their forte is activist scheming, not persuading independent minds. Their mode of politics is to sow anger, hate, and division, with the goal of making all of life political. Such a mode can never have wide, democratic appeal. Another tactic of cultural Marxists (who are many fewer in number than they seem) is to force a stampede of others who like to think of themselves as “on the Left” and are afraid to be marginalized and stigmatized. It seems likely that in any balanced, open culture committed to respectful debate of contrary views, cultural Marxists would soon be exposed for what they are: power-hungry, embittered, intellectually second-rate, and few.

Martin Luther once said that humanity is a like a man who gets up on a horse, falls off one side, then gets up again and falls off the other. Extremes beget opposing extremes. The excesses of the Enlightenment, its intolerant tolerance, led to the ideological tyrannies of the 20th century, from which we have not yet escaped. The opposite of extremism is moderation, and moderation requires balance and alternanza. Balance is difficult and requires more than merely institutional guiderails. Alternanza in politics is supported by a specific moral disposition, what the ancients called the ability to rule and be ruled in turn. To encourage such a disposition in the citizen body was for Aristotle the highest achievement of political education. Classical political philosophy never imagined the modern sort of partisan tyranny that seeks to dominate the soul with all the tools of science and bureaucratic oppression, but its lessons, nevertheless, remain pertinent and its ideals of political health remain sound. A healthy polity, one that creates the conditions for happiness, must be based on rationality, sociability, and respectful cooperation among its citizens. True statecraft begins with soulcraft.