Books Reviewed

On February 19, 1942, almost two and a half months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. Citing the need to protect against espionage and sabotage, the order authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders designated by him “to prescribe military areas…from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate military commander may impose in his discretion.”

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson promptly named Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, headquartered at the Presidio of San Francisco, as the military commander to implement the order. Within two weeks DeWitt established military zones covering Washington state, Oregon, California, and southern Arizona from which “such persons or classes of persons as the situation may require” would subsequently be excluded. Further orders resulted in the exclusion of approximately 112,000 people from the designated areas. Meanwhile, on March 21, 1942, Congress passed Public Law 503, criminalizing knowing violations of such orders. Most of the excluded population spent time in detention camps.

But this skeletal account obviously leaves out a key detail: practically all of the people thus “relocated” (or “evacuated”) were of Japanese ancestry. About a third were Japanese immigrants (the Issei), who were aliens ineligible for citizenship under the naturalization law of the period, but the rest were American-born (mostly Nisei, or second-generation) and hence citizens. In the actual event, however, this further detail of citizenship proved no barrier to removal, nor did it condemn the program constitutionally in the eyes of the United States Supreme Court. Upholding first an initial curfew on the coast, in Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), and then the exclusion itself, in Korematsu v. United States (1944), the wartime Court essentially deferred to what it portrayed as the judgments of military commanders about military necessity “made without the benefit of hindsight.” (In another case, Ex parte Endo, the Court ducked the issue of whether loyal citizens could constitutionally be detained. It gave Ms. Endo her freedom through a disingenuously narrow reading of Executive Order 9066 and Public Law 503 as not authorizing her continued detention.)

By contrast, from World War II down to the present, few scholars have had anything good to say about the relocation. Some solid, objective studies have nonetheless appeared. Particularly useful is Stetson Conn’s careful reconstruction of the relocation decision itself. Conn, a civilian historian with the Army’s Office of Military History, concluded that “the only responsible commander who backed the War Department’s [mass evacuation] plan as a measure required by military necessity was the President himself, as Commander in Chief.” Yet Roosevelt gave the issue little attention. Until mid-February, General DeWitt himself had opposed removing citizens, but then developed his own comprehensive plan. Narrower in geographic focus than the War Department’s subsequent plan, this proposed sweeping in 25,000 Japanese aliens and 44,000 citizens of Japanese descent, along with 64,000 German and Italian aliens.

So whence came the war department’s plan? Conn linked it especially to Major (and soon Lieutenant Colonel) Karl Bendetsen, a mobilized reserve lawyer in the Provost Marshal General’s office. Shuttling back and forth between Washington, D.C., and San Francisco, Bendetsen in effect took every opportunity to ratchet upward the sweep of the proposed evacuation. In late January and early February 1942, Secretary Stimson and Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy themselves edged toward selective removal of citizens from high-risk areas. When the War and Justice Departments reached an impasse on handling citizens, Stimson and McCloy took the issue to FDR on February 11. Reporting the results to Bendetsen, McCloy stated, “We have carte blanche to do what we want to as far as the President’s concerned.” This produced the final rounds of consultations and planning, during which Stimson and McCloy shifted to favor mass removal. Executive Order 9066 followed, along with the orders from Stimson to DeWitt to remove Issei and Nisei alike.

All of which brings us to Michelle Malkin’s In Defense of Internment. Aiming “to provoke a debate on a sacrosanct subject that has remained undebatable for far too long,” Malkin “challenges the religiously held belief that internment of enemy aliens and the West Coast evacuation and relocation of ethnic Japanese were primarily the result of ‘wartime hysteria’ and ‘race prejudice.'” Her “central thesis…is that the national security measures taken during World War II were justifiable, given what was known and not known at the time” (her emphasis).

Besides wanting to set straight the record on the relocation program, she is worried that nowadays “[n]o defensive wartime measure that takes into account race, ethnicity, or nationality can be contemplated, let alone implemented, without government officials being likened to the ‘racist’ overseers of America’s World War II ‘concentration camps.'” In approaching her task, she is “not a professor whose tenure relies on regurgitating academic orthodoxy about this episode in American history.” Instead, she describes herself as possessing the credentials of “an open mind, a willingness to reject political correctness as a substitute for thought, and the ability to view the writing of history as something other than a therapeutic indulgence.”

* * *

On Malkin’s telling, what was known at the time consisted partly of very public events. She relates how a Japanese pilot, returning from the Pearl Harbor attack with a punctured fuel tank, crash-landed on Niihau, a small island northwest of Honolulu, and received succor from a Japanese-American couple and a laborer born in Japan—even after they learned of the Pearl Harbor attack. The husband and wife went so far as to terrorize their fellow islanders and assist the downed pilot in an unsuccessful attempt to make radio contact with Japanese forces. Finally, a native Hawaiian couple, “[i]n their own ‘Let’s Roll’ moment of heroism,” overpowered and killed the pilot. The Japanese-American husband then committed suicide. According to naval intelligence officers in late January 1942, the episode revealed the potential for further collaboration, in the event of an invasion, between ethnic Japanese in the islands, both citizens and aliens, and Japanese forces.

Malkin’s focus then broadens to the whole Pacific theater. After describing the shelling of oil fields near Santa Barbara by a Japanese submarine on February 23, 1942, she shifts back to early December. “[T]here were many phony rumors of sabotage and erroneous reports of attacks,” she notes, but “for every false alarm, there were many more real and unsettling forays along our shores that, when added to Japan’s shocking military triumphs abroad, rightfully heightened America’s anxiety.” Japanese submarine activity off Hawaii and along the West Coast reinforced the shocked reactions to Pearl Harbor itself and to Japan’s successes against American, British, and Dutch forces and possessions in the western Pacific. An opinion piece by Walter Lippmann, “the most influential columnist and preeminent liberal intellectual of the day,” raised concern about “the enemy alien problem on the Pacific Coast, or much more accurately, the fifth column problem,” as Lippmann described it. Malkin also relates the efforts of Japan to use schools and patriotic societies in Hawaii and on the West Coast to retain the loyalties of both Issei and Nisei.

More important still for the decision-makers were intelligence reports. These disclosed a spy ring operating out of the Japanese consulate in Honolulu and another on the West Coast, each seeking to draw in Issei and Nisei as eyes and ears. In the aftermath of the December attack, moreover, naval and army intelligence agents stressed that spy networks were still in place. While doubting that the bulk of the Nisei were disloyal, the same agents as well as civilian investigators operating under FDR’s orders suggested several thousand of them did pose threats. In late January 1942, the commission under Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, appointed to investigate the Pearl Harbor disaster, reported that Japanese spies in Hawaii had aided the attack. What gave still greater impetus was the Army’s decrypting effort, code-named magic, which broke the Japanese diplomatic codes. Army and Navy cryptologists were able to read the communiqués sent via commercial cable companies to and from Japan’s embassy in Washington and its consulates in key cities. The magic reports themselves were highly classified with only a few direct recipients, among whom were Roosevelt himself, Secretary of War Stimson, and Assistant Secretary McCloy, but not General DeWitt, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, or Attorney General Francis Biddle. The information contained in the reports nonetheless went to a broader group in sanitized form to disguise the source. (Public acknowledgement of magic occurred just after World War II; declassification of the full set of documents began in the 1970s.)

Malkin finds evidence within both the magic intercepts and their sanitized versions confirming the field agents’ reports on Japanese espionage efforts within the continental United States and Hawaii, including the successful targeting of some Issei and Nisei. While it is true that magic reports on domestic espionage ceased once Japan’s diplomatic and consular operations in the United States closed at the outbreak of war, magic had already lent credence to the threat. Specifically, she argues, pre-war magic reports about spying help explain the early evacuations from Terminal Island in Los Angeles Harbor (about which more below) and Bainbridge Island in Puget Sound, near the Bremerton Naval Shipyard. In addition, the puzzling extension of the exclusion area to include southern Arizona becomes understandable, for magic had indicated that in case of war Japan would use Mexico as a base for its American intelligence operations.

Moving into an examination of the “internment” program in operation, Malkin provides useful clarifications. Strictly speaking, the “internment” label itself applied only to the detention of enemy aliens. Within days of the Pearl Harbor attack, federal officers, mainly in the Justice Department, began picking up German, Italian, and Japanese aliens already identified by intelligence sources as risks. Within a week, 2,451 were in custody nationwide, and by the end of the war 26,655 (11,229 of them Japanese) had been detained at one time or another, in 46 well-guarded camps around the country. Existing legislation, including the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, served as the basis for these detentions.

By contrast, persons evacuated under the War Department’s West Coast program were not internees (although several thousand Nisei became such after renouncing their American citizenship). The Army’s initial effort was to induce voluntary movement from the restricted military areas to locations further east. A variety of reasons, including limited individual resources and opposition from inland communities, made this approach unworkable, however, and mandatory removal followed. The evacuees went first into assembly centers up and down the coast, and then to ten relocation camps running from eastern California to Arkansas. These were run far more loosely than the internment camps for enemy aliens, and the civilian War Relocation Authority set up a program for screening the evacuees and granting leaves to those with acceptable records who could find employment outside the western states. By December 1944, when the mandatory program ended, about 35,500 had left the camps under these conditions. Another 4,300 college-age evacuees also received leaves, to study outside the West Coast.

How well does Malkin achieve her goals? Perhaps the first thing to note is that when In Defense of Internment appeared in August 2004, the ensuing exchanges in cyberspace proved she had succeeded in stimulating debate. Critics blogged on and on, for pages and pages, with Malkin giving as well as she took. The evacuation/relocation program of World War II clearly remains a hot-button issue, not least because of its salience in the debates accompanying our own war on terror, but also because it had truly unsavory aspects. On the latter front, Malkin quickly disclaimed arguing that racism played no role. She did not intend to write a comprehensive account that would re-plow much-tilled ground.

* * *

By my reading, Malkin offers a largely fair assessment of the relocation program in operation, once the underlying decision occurred. It is not an assessment that will please those who equate it with the Nazis’ death camps. To be sure, the relocation camps were “concentration camps,” but in the older military sense: camps for concentrating and controlling a particular population. Life in them was spartan, but the War Relocation Authority sought to turn them into self-contained and self-governing communities. In this regard, success varied somewhat from camp to camp, with the center at Tule Lake, California, posing a particular problem after malcontents from other camps, along with several thousand evacuees who refused to swear loyalty to the United States, were moved there in July 1943. Overall, Malkin agrees that the actual removal and detention remained something of a work-in-progress after the first orders came down, and on occasion the program was bungled.

Where Malkin goes astray in handling the actual evacuation and ensuing detention, I believe, is in comments that range from off-putting and irrelevant to needlessly inaccurate. In the off-putting and irrelevant category is her observation that the cramped, sometimes crude quarters in three of the assembly centers were subsequently used by military personnel. This recalls Justice Hugo Black’s majority opinion in the Korematsu case: “hardships are part of war, and war is an aggregation of hardships. All citizens alike, both in and out of uniform, feel the impact of war in greater or lesser measure.” But the issue is whether the people caught up in the relocation should have been subjected to the hardships in the first place.

Needlessly wrong is her assertion that “[i]n upholding the constitutionality of the exclusion orders, the U.S. Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States ruled that no one of Japanese ancestry was compelled ‘either in fact or by law’ to enter a relocation center.” What Justice Black actually wrote and meant was something quite different. He wrote that had Fred Korematsu complied with orders and reported to an assembly center (rather than remain at large in the military area, as he did), the Court could not “say either as a matter of fact or law, that his presence in that center would have resulted in his detention in a relocation center.” Black’s reasoning on the point was lawyerly: some who reported to assembly centers were “released upon condition that they remain outside the prohibited zone until the military orders were modified or lifted.” Hence there was a small chance that if Korematsu had complied, he would not have been involuntarily taken to and detained in a relocation camp. By this route, the Court in Korematsu avoided reaching the constitutional validity of the detention program itself. But Black also explained that a separate part of the overall program (not at issue in Korematsu) was to “go under military control to a relocation center[,] there to remain for an indeterminate period until released conditionally or unconditionally by the military authorities.” In short, Black conceded that “in fact” people were involuntarily detained in the relocation centers, and he carefully avoided stating that “by law” the program entailed no involuntary detention.

The brunt of criticism has fallen on Malkin’s claims about the relocation as a response to a military threat perceived as real at the time. Unfortunately, she does not carefully sort out what was known at the time from what was not. One of Malkin’s blogger critics quickly observed that the Japanese submarine’s shelling of the oil field near Santa Barbara on February 23, 1942, could hardly have been a factor in the key decisions of the preceding several weeks. In response, Malkin noted that she had linked the shelling to the speeded-up evacuation of Terminal Island on February 25. This comes about 80 pages later.

Similar difficulties are explained away less easily. After describing the shelling episode, Malkin turns to Japanese operations in the Pacific immediately after Pearl Harbor and to Secretary Stimson’s fear of raids against the American mainland. The reader then learns that Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, a Japanese naval commander, had precisely this in mind. Relegated to a footnote is Malkin’s qualification that the source from which she drew the episode “states that other Japanese officers were unenthusiastic about Yamaguchi’s plan.” She does not mention at all that Yamaguchi presented his plan at a conference on February 20-23, 1942, on board a Japanese battleship. Did Yamaguchi’s plan help shape American thinking relating to the evacuation? Could it have? One suspects not. (Malkin covers herself, perhaps, by noting that similar ideas circulated in the Japanese media.)

Another problem of sequence emerges when the reader learns “[i]n the Philippines, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and statesman Carlos Romulo described massive Japanese espionage activity in the country prior to the war.” Malkin then provides several details. The source is a book by Romulo, one written and published following his arrival in the United States in June 1942. A bit further on, as added evidence for why Americans in late 1941 and early 1942 could reasonably have worried about the enemy in their midst, the reader learns that “Japan’s surrender in 1945 came as a traumatic blow to many Hawaiian Issei,” and that Tomoya Kawakita, a Nisei who served in Japan’s army, “tortured scores of American POW’s held in a Japanese prison camp.” The torture occurred during the war, of course, and Kawakita was exposed after the war once he returned to Los Angeles.

* * *

Malkin would have done better by redirecting her efforts into a more careful investigation of the true role of intelligence reports in the decision to relocate the Issei and Nisei. The episode on Niihau Island in Hawaii, involving the downed Japanese pilot returning from the Pearl Harbor raid, is one example. The behavior of the Japanese-American couple that aided the pilot was “shockingly disloyal,” as Malkin correctly labels it, and naval intelligence was right to take it seriously. Yet with respect to the naval intelligence reports on the episode that were filed in late January 1942, just after the release of the report by the Roberts Commission, Malkin only concludes that they “reinforc[ed] Roberts’s assertions and, presumably, further exacerbat[ed] concerns among military leaders about the so-called ‘Japanese situation'” (my emphasis). Did the Niihau reports from late January actually affect assessments of the situation on the West Coast? We don’t find out, or even learn who received them. But one may doubt whether they added much to the felt urgency of the situation in late January, as suggested by Malkin, because on January 7 the Roberts Commission itself had heard similar testimony about the Niihau incident from Lieutenant George P. Kimball, a naval intelligence officer in Hawaii. (Malkin does not mention Kimball’s testimony.)

As another example, Malkin writes, “Terminal Island in Los Angeles Harbor…had been singled out in magic messages [note the plural] as a hotbed of Japanese espionage activity” (my emphasis). But among the magic decrypts she references in the book, I find only one, from May 9, 1941, that bears on Terminal Island. She elsewhere quotes language from it twice. As far as I can determine, it is also the only magic message on the point that appears among the many included in the book’s ample appendices. The message, from Japan’s Los Angeles consulate, included the brief statement, “We have already established contacts with absolutely reliable Japanese in the San Pedro and San Diego area, who will keep a close watch on all shipments of airplanes and other war materials….” Does this remark reveal Terminal Island as “a hotbed of Japanese espionage”? In any case, Malkin’s “hotbed” comment itself, as quoted above, carries no footnote citation, but is followed by a discussion of a detailed report from naval intelligence about the Terminal Island population. The latter report established a good case for removing several hundred Kibei (Nisei who had spent time in Japan). Whether it supported a broader removal is less clear, for in a sentence not quoted by Malkin, it stated, “there do exist in this colony a great many known and trusted nisei…who are at present acting as observers and informers for the Naval Intelligence Service and the F.B.I.” Did magic tip the scales? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

A similar question arises from a comment by Malkin about magic’s impact on General DeWitt, whose own plan involved large-scale evacuation even though he opposed indiscriminate removal of the Nisei. Malkin writes, “It appears that DeWitt did not have clearance to magic in early 1942, but he did have access to intelligence reports that were derived from magic—reports that warned of Japanese-controlled espionage cells up and down the West Coast.” The magic and magic-derived reports undeniably testify to espionage activity, but did they disclose “Japanese-controlled espionage cells,” either to DeWitt or to his superiors in Washington who made the actual decision? From the evidence, this seems less certain.

Here Malkin could have done real service. By the time she wrote her book, critics had already roundly attacked claims by another author (David Lowman) about the warnings provided both by magic and by other intelligence reports on the dangers posed by the West Coast Issei and Nisei. Thus forewarned, Malkin might have carefully and systematically sorted out, as best the evidence allows, the actions of several groups that were or may have been involved in espionage activity: Japanese consular personnel, the disaffected whites and blacks whom Japan clearly hoped to recruit, sympathetic Issei, similarly-inclined Nisei within the civilian population, and Nisei in the armed forces (mentioned in one of the decrypts). She also might have systematically sifted information that Japanese consular officials derived from open sources—she mentions the Los Angeles Times—from what “presumably was based on surveillance or espionage by Japan’s agents.” One wonders, too, how many of the culprits had already been interned as enemy aliens.

Indeed, Malkin never quite brings together the argument that for the decision-makers in Washington, D.C., military necessity, as inferred from sources known at the time, was the reason for the indiscriminate mass evacuation that actually occurred. During congressional testimony in 1984, to be sure, Colonel Bendetsen and Assistant Secretary McCloy recalled that magic had influenced the removal decision over 40 years earlier, but the recollections of old men are suspect. Malkin simply does not examine in sufficient detail the shift in thinking during the key period of February 17-20, 1942, away from a more selective removal. And some evidence points elsewhere, away from military necessity. During this period, for example, Secretary Stimson had before him a letter from West Coast congressmen, one that FDR had forwarded to him on February 16 for a reply. The congressmen recommended evacuation of “all persons of Japanese lineage…from all strategic areas.” They also called for enlarging the areas to “encompass the entire strategic area of the states of California, Oregon and Washington, and [the] Territory of Alaska.” To what extent did political considerations tip the decision? Malkin avoids such issues.

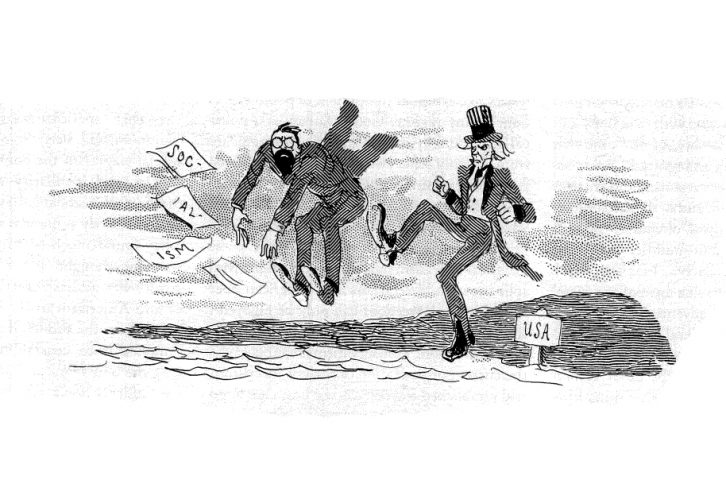

In the end, the removal took a particular course, one which swept up 112,000 people, many of them citizens, from a vast area. What does the experience teach post-9/11 America? Curiously, Malkin makes only a limited connection despite the implied linkage in the book’s title. (She devotes more attention to lambasting the critics of the relocation, who in the 1980s obtained an official apology from Congress as well as monetary compensation for surviving evacuees.) Although defending “racial profiling” in the aftermath of 9/11 on a variety of grounds, she does not use the World War II evacuation to argue for wholesale detention today.

What then is the moral for Malkin? This: don’t be misled by the pandering of “civil rights absolutists” intent on using “legends” about the World War II experience as “multicultural group therapy…to color and poison the current national security debate.” Are there specific lessons from the removal? Vigorously gather intelligence. Prevent people in suspect categories from holding sensitive civilian and military jobs. Avoid hard-to-win jury trials of subversives. Guard the secrets. As she recognizes, but without much recognition of the irony, the leading governmental opponents of mass relocation in 1942 said pretty much the same things.