Books Reviewed

A review of In a Cardboard Belt!: Essays Personal, Literary, and Savage , by Joseph Epstein

, by Joseph Epstein

Joseph Epstein has chosen the Samuel Johnson route to literary renown, in which familiarity breeds affection, and in four decades of brilliant writing he has become his own Boswell. If you have delighted in any of his 19 books, a quarter of which are autobiographical, it's hard not to feel that you know the fellow. Faithful Epstein readers can tell you his opinions on life, literature, and man; what he eats, wears, and listens to; how many times a day he shaves; that he takes in a quick paragraph at red lights; how thin his hair and how thick his paunch; even a thing or two about his bathroom reading habits about which I'll speak no further.

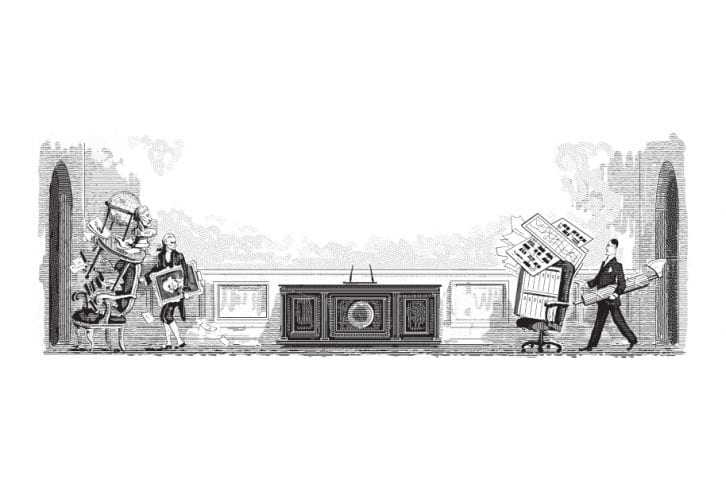

Epstein, retired in recent years as editor of the American Scholar and as lecturer in literature at Northwestern University, has published books on divorce, ambition, envy, snobbery, friendship, and Tocqueville, and two collections of short stories. But he is best loved for his essays; this is his tenth collection of them. Until In a Cardboard Belt! every collection was in theme either entirely literary or entirely personal. This book breaks that tradition. In it are essays on his father's passing, movies, travel, dining, editing, writer's block, and the strangely gratifying unhappiness of academics; there are moving appreciations of W.H. Auden, Marcel Proust, and John Keats, and fierce depreciations of Edmund Wilson, Mortimer Adler, and poetry prizes. The result is an unusually broad portrait of a thinking man doing his stuff.

Epstein is one of the handful of writers in America today whom one can pleasurably read both for substance and style. His writing sparkles with observation and humor: "I've had enough of [dinner] specials generally, and I have never met anyone who, when presented with more than four specials by a waiter, can recall the first two." "One of the problems with the world, I begin to discover, is that there are too many people in it just like me." He can be pithy—"Charm is the desire to delight, light-handedly executed"; "Writing cannot be taught, but it can be learned"—and even profound: "Jews need Chinese restaurants." His opinions are sharp, but never bitter; learned, but never pedantic. He can enjoy being whimsical, but you won't catch him meandering. The J. Epstein style remains thick orderly paragraphs in seamless succession, an elegant discursiveness and easy authority, and a polished conservative sensibility.

In his personal essays, as ever, Epstein reveals himself to readers to an astonishing degree. In "Talking to Oneself" he opens to us his journal, in which entries dating back nearly 40 years describe his gambling habits and insomnia, or show him brooding on whether posterity will publish his journal posthumously ("I have tried to drop as many names as possible in it, for a namey journal can be greatly amusing"). He has reached 70, and age has always been an Epstein preoccupation:

Seventy poses the problem of how to live out one's days…. I like the notion of the French philosopher Alain that, no matter what age one is, one should look forward to living for another decade but no more…. A year or so ago, my dentist told me that I would have to spend a few thousand dollars to replace some dental work, and I told him that I would get back to him on this once I had the results of a forthcoming physical. If I had been found to have cancer, I thought, at least I could let the dentistry, even the flossing, go. Turning seventy, such is the cast of one's thoughts.

Two themes run through the 32 essays collected here. The first is a sustained reflection on the coarsening of culture. Vulgarity has spread, the national culture of his youth has fragmented into subcultures, and celebrity is increasingly awarded to the undeserving. But the worst trend, whose baleful sweep he claims we have yet to measure, is the "triumph of youth culture." Epstein remembers "when the goal was to be adult as soon as possible, while today—the late 1960s is the watershed moment here—the goal has become to stay as young as possible for as long as possible." Longevity and prosperity mean that today "no one is required to depart adolescence until heavy dementia sets in." Yet Epstein possesses too much self-knowledge to be a curmudgeon:

If the game is to be played decently at seventy, one must hark back as little as possible to the (inevitably golden) days of one's youth, no matter how truly golden they seem…. Start talking about thenadays and one soon finds one's intellectual motor has shifted into full crank, with everything about nowadays dreary, third rate, and decline and fallish. A big mistake. The reason old people think that the world is going to hell, Santayana says, is because they believe that, without them in it, which will soon enough be the case, how good really can it be?

If the tone of his personal essays is comic, his literary essays are earnest. Literature, for Epstein, is serious business, and relentless clarity in intellectual matters is the book's second theme. He believes the critic's task is to elucidate and clarify, to champion the good and expose the false, to entice and illuminate rather than to dazzle and impress. He absolutely refuses to foist an obscure sentence on his small but loyal public. One of his favorite quotes, appearing in half of his books, is T.S. Eliot's remark on Henry James: "He had a mind so fine no idea could violate it." Epstein distrusts "ideas," if they entail replacing facts with concepts, and honest inquiry with bogus, cocksure systems. "His own mind operated above the level of ideas," Epstein says in praise of the French writer Paul Valéry. "You will find few words in Valéry that end in ism, and those that he does use he brings in only to mock. ‘It is impossible [wrote Valéry] to think seriously with such words as Classicism, Romanticism, Humanism, Realism, and the other -isms. You can't get drunk or quench your thirst with the labels on bottles.'"

* * *

Nowhere do abstraction and pomposity combine to more hateful effect than in the prose of our academics and intellectuals. Epstein calls them "little demons of ignorant subtlety," whiny, demoralized loudmouths distinguished by their false learning, surly politics, and mediocre minds—especially those so assiduously ruining the study of serious literature:

Now it almost seems as if the annual MLA meetings exist primarily for journalists to write comic pieces featuring the zany subjects of the papers given at each year's conference. At these meetings, in and out of the room the women come and go, speaking of fellatio, which, deep readers that they are, they can doubtless find in Jane Austen.

He writes of critic George Steiner: "Nearly every sentence he indites contains the title of a book, the name of the author, an -ism or an -ology, foreign phrases, and plenty of quotation marks to go around…. One finds little evidence in Steiner's writing that he knows either man or life, only ‘ideas.'" Yale professor Harold Bloom also "likes to roll around in his rich pollution of -isms." Bloom, says Epstein, in the book's most devastating and amusing attack,

is that most comic of unconscious comic figures: the academic Dionysian, calling for higher fires, more dancing girls, music, and wine, all from an endowed chair. His literary taste runs to the hot-blooded, long-winded, and apocalyptic: Blake, Whitman, Nietzsche, D.H. Lawrence, Norman Mailer are among the writers who light our aging professor's fire. Apart from Shakespeare, Bloom's great culture heroes are Emerson and Freud, who, in combination, yield a gasbag with a dirty mind.

Epstein's heroes, by contrast, exemplify the subtle, exquisite, sober, refined. In "Books Won't Furnish a Room," he recounts his decision to reduce his library from 2,000 volumes to 400. Five writers alone are preserved in their entirety: Henry James, Gibbon, Santayana, Proust, and Max Beerbohm. "Some people are born to lift heavy weights," wrote Beerbohm. "Some are born to juggle with golden balls." "The golden jugglers," writes Epstein,

are the ones with wit, the ability to pierce pretension, and the calm detachment to mock large ideas and salvationist schemes. They eschew anger and love small perfections. They go in for handsome gestures…have wide sympathies, and understand that a complex point of view is worth more than any number of opinions.

Epstein predicts that Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer will be the only modern writer still read in fifty years with the same interest, for his art was devoted to the study of "human nature, a subject on which, despite the best efforts of science and social science, we remain in the same centuries-long state of high ignorance." For Singer "every human being was an exception who proved no rule. That ought to be the credo of every artist." In "Is Reading Really At Risk?" Epstein furnishes as fine a statement of his faith in the power of literature as one will find:

Ours is an age of abstractions. ‘Create a concept,' Ortega y Gasset said, ‘and reality leaves the room.' Careful reading of great imaginative writing brings reality back into the room, by reminding us how much more varied, complicated, and rich it is than any social or political concept devised by human beings can hope to capture. Read Balzac and the belief in, say, reining in corporate greed through political reform becomes a joke; read Dickens and you'll know that no social class has any monopoly on noble behavior; read Henry James and you'll find the midlife crisis and other pop psychological constructs don't even qualify as stupid; read Dreiser and you'll be aware that the pleasures of power are rarely trumped by the advertised desire to do good.

At 70, Epstein's awe for the mystery of life is greater than ever; never has he been so confident that to its permanent questions we supply only impermanent answers. What remains then but to become an ironist, a comedian, an amused observer? Full of years and experience, content yet still curious, he feels "it is natural to begin to view the world from the sidelines, a glass of wine in hand, watching younger people do the dances of ambition, competition, lust, and the rest of it." But this book proves that America's finest essayist isn't ready to hit the showers just yet.