Books Reviewed

A review of Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding, by Steven K. Green

The American revolution is still being fought on many fronts, and the United States refounded several times each year, as new books explain the real sources and real meaning of America’s beginnings. In the past decade, dozens of scholarly—and not-so-scholarly—books have sought to explain, in particular, the place of religion in the American Founding. Popular writers and self-proclaimed historians generally claim that our fathers brought forth a Christian nation, while scholars and academic historians contend either for a strictly secular founding or for one with both religious and secular elements. Inventing a Christian America, by Willamette University law professor Steven Green, is the latest ambitious effort in this contentious field.

Green looks at a broad time frame (roughly 180 years) and a wide range of issues. What influence, if any, did early Puritan settlements a century before have on the founding? Can the founders’ views on religious liberty, republican government, and constitutionalism be traced to the Puritans’ idea of covenant? What effect, if any, did the Great Awakening in the early 1700s have on the founding? What role did clergymen play in inspiring, justifying, and promoting the American Revolution? What role did belief in divine Providence play in the founding? What religious beliefs can we discern in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution?

“Myth,” as Green uses that term in his subtitle and throughout the book, means simply “identity-creating narratives”; he insists that such myths are not necessarily untrue. He wants merely “to explain how the ideas of America’s religious founding and its status as a Christian nation became a leading narrative about the nation’s collective identity.” Nevertheless, Green treats every element of the “myth” as false throughout and tries to prove its falsehood at every turn.

* * *

The book’s treatment of the early colonial period is quite informative and well supported, emphasizing the “melding [of] theological and Enlightenment concepts” as “Puritan-Calvinist patterns and ideas informed revolutionary and constitutional ideology.” His discussion of the founders’ own religious beliefs starts with the same balance and nuance, arguing that the “portrayal of the founders as religion-despising deists is as inaccurate as the claim that they were all born-again Christians.” He even employs the term I use in The Religious Beliefs of America’s Founders (2012), “theistic rationalism,” and occasionally strengthens the “theism” element by making it the noun rather than the modifier. Green soon abandons any notion, however, that religious influence “melded” with Enlightenment thought or that Christianity “informed” the founders’ views. Suddenly, it’s all rationalism and no theism, with any reference to divine Providence—even in private writings—dismissed as political rhetoric. How does Green know the founders’ motives and intent? Is there a reason to doubt their sincerity? He gives none. Even if we are skeptical of public pronouncements, why wouldn’t private correspondence, diaries, and memoranda reliably convey a person’s beliefs? After warning against simply taking religious statements at face value and against isolating favorable quotes, Green does that very thing in support of his own position.

The author’s negligence only becomes worse in his discussion of the major founding documents. Although he admits that there were “few committed deists in America” (naming three minor characters who had nothing to do with any of the founding documents), Green claims that the Declaration of Independence is entirely deistic. The problem is that, in drafting the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson intentionally used “religiously ambiguous” language—as Green correctly calls it at one point—in order to garner maximum support for independence. Everyone, regardless of religious preference, can and does read his own beliefs into terms like “nature’s God” and “created equal.” Even today, Christians see Christianity and secularists see secularism. Green argues that the Declaration reflected “the thought of the day,” which, of course, is what Jefferson later maintained. But Green assumes without proving (contrary to what he argued earlier) that the thought of the day was exclusively a product of the Enlightenment. What of Protestant influence and the theism that he contends was central to the beliefs of those who wrote and approved the Declaration? What of Aristotle and Cicero, whom Jefferson listed among his influences?

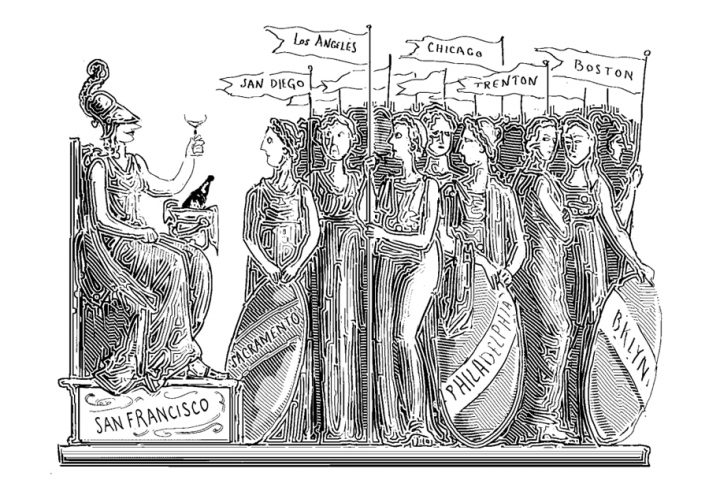

The book’s final chapter, “The Birth of a Myth,” is the most interesting and important contribution. Here, Green makes a plausible, well-argued case for the way the notion came about that America was established as a Christian nation from the start, and traces the myth’s growth and development from the early to the mid-1800s. In his telling, this narrative was “consciously…constructed by the second generation of Americans in their quest to forge a national identity.” At various critical moments, it was “dusted off” and embellished to meet the nation’s needs for unity and for a higher purpose. Green also identifies some of the myth’s key transmitters and embellishers, concluding with Alexis de Tocqueville. Although it isn’t fair to review the book I wish Green had written, I can’t help thinking that he should have focused on the myth’s creation, enhancement, and transmission, and carried that story to the present day. It is uncharted territory that needs to be, and could be, explored in a single volume of this size.

* * *

One other disappointing aspect of Inventing a Christian America is Green’s propensity to fall prey to some of the same faults he criticizes in others—the worst of which is his tendency to make broad, sweeping claims without substantiation or, at least, some qualification. For example, he claims that a “majority of the delegates [to the Constitutional Convention] professed rational or heterodox beliefs,” when scholars in fact hardly know anything about the beliefs of many of the delegates. He says that “a general consensus about the nation’s secular foundation existed during the founding period” and that “the Constitution was universally seen as a secular document,” but provides no evidence except endnotes directing readers to modern commentators, not writings of the time. On the strength of a few quotes from 18th-century ministers, he concludes that “people overwhelmingly viewed the national government as being founded on secular, rational principles, rather than on religious ones.” What evidence is there that these particular ministers represented an “overwhelming” majority of the “people”? What’s more, he asserts that “a majority” of “the founding generation” opposed using “government to promote [moral virtue] by financially supporting religion.” How could he possibly know what a majority of the entire generation thought about this issue? How would one even go about researching that?

Steven Green has written an ambitious book that, despite significant limitations, manages to break some new ground in the study of religion and the American Founding.