In his 1888 essay, “Why Great Men are Not Chosen Presidents,” Britain’s James Bryce wrote that “the ordinary American voter does not object to mediocrity.” Yet by the time of Bryce’s writing, less than one score removed from Abraham Lincoln’s day, America had already produced eight presidents who Bryce said were “statesmen in the European sense” or who “belong to the history of the world.” If Bryce could see the dearth of presidents over the past half-century fitting either of those descriptions, he might recalibrate his assessment of earlier voters’ expectations.

In recent voters’ defense, however, they can hardly help pulling the lever (or licking the stamp) for mediocrity when our current presidential selection process serves up little else. It’s hardly surprising, moreover, that this process was designed (to the extent it was designed at all) by the left wing of the Democratic Party. Republicans then adopted it without much debate. Nor should it be surprising that this ill-advised system hurts Republicans more than Democrats.

The current process is an outgrowth of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The New Left was frustrated because, though Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy and New York Senator Robert Kennedy battled closely in the primaries, Lyndon Johnson’s vice president Hubert Humphrey sat out those contests yet walked away with the nomination. He was the last nominee of either party to win the honor without entering a single presidential primary. Those dissatisfied with Humphrey’s independence or moderation successfully pushed for a post-election review of party rules led by Senator George McGovern and Representative Donald Fraser. The McGovern-Fraser Commission sought to replace the old process for selecting presidential nominees, in which Democratic party leaders would decide on a nominee at the convention. Primary elections, previously regarded as non-binding recommendations to the convention from the electorate, became the deciding factor in choosing candidates. To the delight of party radicals and the dismay of party regulars, the first great success of the new rules was the nomination of McGovern in 1972, who went on to win one state and the District of Columbia. Republicans, not wishing to be seen as insufficiently “democratic,” had already obligingly decided to follow suit.

Backing a Loser

The resulting system of direct primaries and caucuses was supposed to empower voters, but things haven’t played out quite as expected. Political science professors Marty Cohen, David Karol, Hans Noel, and John Zaller write in The Party Decides (2008) that “elected officials, top fundraisers, interest group leaders, campaign organizers, and ordinary activists” work to “scrutinize and winnow the field before voters get involved.” This winnowing is sometimes called, somewhat delicately, the election before the election; sometimes more plainly the “money primary.” These power brokers unite “behind a single preferred candidate, and sway voters to ratify their choice.” Their “control of campaign resources (money, knowledge, labor)” usually seals the deal, especially on the Republican side. The new system also greatly empowers the press, which decides how to portray candidates, what issues to amplify or mute, and when to assign momentum. As Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick observed in Dismantling the Parties (1978), written just a few years after the new system replaced the old,

Advocates of the direct primary intended to wrest control from the bosses and return it to the people; presumably they did not intend to vest power in Walter Cronkite and other media moguls or to speed the development of a personalist politics with standards and practices more relevant to entertainment than to public affairs.”

Increased media control hardly affects the two parties equally. Perhaps, then, it is not a coincidence that the system has prompted them to act in different ways. Republicans have shown a maddening tendency to default to the “next in line” candidate—the candidate they rejected the last time. Over the past 50 years of open primary battles (those without an incumbent president from the party in question), Republicans have gone with their next-in-line candidate—i.e., the runner-up in the popular vote during their most recent primary cycle not featuring an elected GOP incumbent—five out of seven times (71%). Over that same span, Democrats have gone with their next-in-line candidate just one out of nine times (11%).

On the flip side, four Democrats over the past half-century have basically come out of nowhere to win their party’s nomination. As Gallup observed in the summer of 2007, Bill Clinton, Michael Dukakis, and Jimmy Carter “were all virtual unknowns who rose from obscurity to take their party’s nomination.” The next year, Barack Obama beat Hillary Clinton after serving just half a Senate term. Meanwhile, the only Republican who has come out of nowhere in the past 50 years—though he was hardly an unknown—was Donald Trump.

Four of the five out-of-nowhere nominees became president (only Dukakis lost), while only two of the six next-in-line nominees did so—with none winning since the 1980s. Suffice it to say that regularly elevating last time’s loser over new blood hasn’t served Republicans well. Nor has this merely been a product of conservatives’ inherent discomfort with change. It wasn’t the conservatives who picked Bob Dole, John McCain, and Mitt Romney. They were the picks of the donors, the consultants, the establishment—and the press corps.

Republican nominations follow a predictable pattern. As analyst Henry Olsen observed in 2014 (“The Four Faces of the Republican Party,” The National Interest March-April issue), Republican voters consist of four “remarkably stable” groups: moderates or liberals (many of whom aren’t even Republicans but vote in open primaries); “somewhat” conservatives; very conservative Evangelicals (plus some members of other religious groups who focus on social issues); and very conservative limited-government voters. The latter two groups make up the movement conservatives, but even combined they constitute only about a third of all voters in Republican primaries. In comparison, nearly half of the Republican electorate is made up of the “somewhat” conservatives—who, Olsen writes, “always back the winner.”

That was true even in 2016, when Ted Cruz won both parts of the movement conservative vote, but Trump beat Cruz among less conservative voters. Trump may have gone on to govern as the most conservative president since Ronald Reagan, and he certainly provided a welcome rebuke to a complacent, incompetent establishment. But even as an outsider, he won in the same manner as all prior nominees in recent decades—by winning among “somewhat” conservatives. He did so when the establishment failed to unite behind a single candidate in an inordinately large field, suggesting that his victory probably didn’t mark a sea change in how Republicans select presidents. Rather, it was an aberration (an outsider victory by a non-politician) that nevertheless followed familiar patterns in terms of which voters cast the deciding votes. Those patterns are likely to continue.

Battle of the Unemployed

Although Trump and Romney are opposites in most respects, both, like McCain before them, were non-consensus (i.e., non-majority) picks. Trump won just 40% of the votes cast before Cruz dropped out, Romney 40% before Rick Santorum dropped out, and McCain 38% before Romney dropped out. About the only thing that McCain, Romney, and Trump have in common—aside from having effectively secured the nomination with far less than majority support, before Republicans in many states even got to vote—is that it’s hard to find a Republican who likes all three of them.

By repeatedly nominating non-consensus candidates, Republicans reveal not only divisions in the party but also profound weaknesses in the current process. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln trailed badly on the first ballot at the GOP convention but picked up steam in subsequent votes as it became clear he was more of a consensus choice than the first-ballot winner, his eventual secretary of state William Seward. But the current process is effectively a one-ballot process—although rather than being put forward for consideration by party leaders, candidates must now zealously put themselves forward over a two-year span.

This keeps many potentially strong candidates from running. To cite just a few examples: Representative Jack Kemp sat out the 1996 race because he didn’t want to spend two years raising money. Representative Paul Ryan sat out the 2012 race, despite being Obamacare’s most prominent opponent, partly because he trailed others in pulling together a campaign organization (thereby ceding the field to the man who launched the Obamacare prototype). And Senator Tom Cotton is sitting out 2024 because he doesn’t want to engage in the two-year slog. Whether these men would have won or not, the campaign and party almost surely would have benefited from their articulate contributions to debates.

John F. Kennedy announced his candidacy on January 2, 1960, ten months before the election. Trump announced his latest candidacy on November 15, 2022, almost 24 months before the next election. This ever-lengthening process has had the strange effect of restricting the race mostly to candidates who are jobless—at least in a political sense. Over the past 30 years, of all candidates receiving even 1% of the Republican primary vote in open primary battles, 61% (14 of 23) didn’t hold political office during the year of the election. Of the 39% who did hold office, almost all (seven of nine) were senators or House members—the next best thing to not having a job. Even though being a governor is arguably the best preparation for being president, only two sitting governors in the past 50 years have gotten even 1% of the GOP primary vote (George W. Bush and John Kasich). Over that span, no sitting cabinet secretary has reached the 1% mark. It’s hard to run for president under the current system if you have real work to do.

Even governors who do run generally don’t fare well, probably for the same reason they often don’t run. Scott Walker, who successfully took on Wisconsin’s public-sector unions in a high-profile battle that gained national attention, was out of the 2016 presidential race by September of 2015. If Florida governor Ron DeSantis enters the 2024 race and does well, as it certainly appears he will, it will be because he overcame the challenges that this flawed system poses to anyone with a meaningful day job.

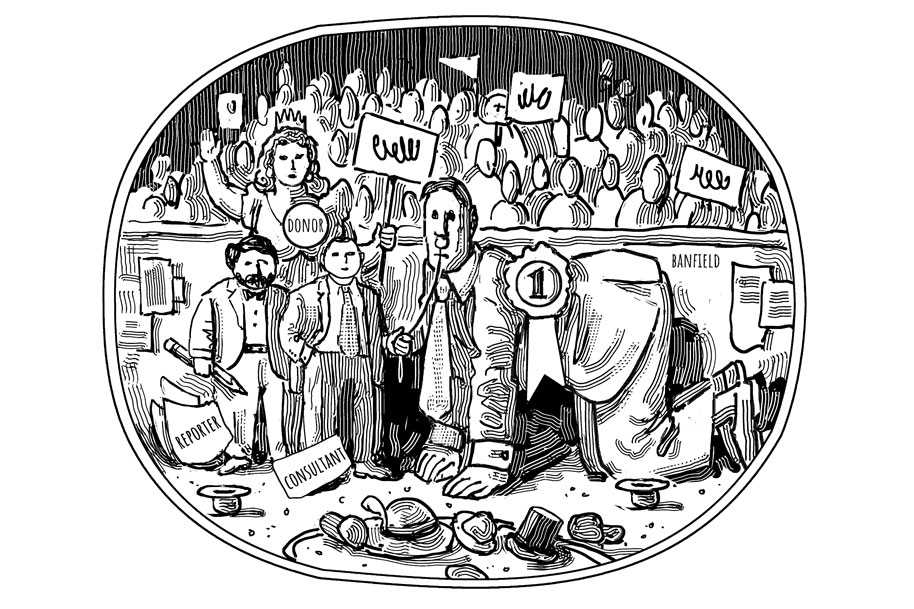

In short, Republicans are basically playing by the Democrats’ rules, to their detriment. They are using a system that elevates donors, consultants, and reporters, while marginalizing the party’s grassroots base. As a result, Republicans routinely end up with about the worst type of candidate: a non-consensus establishment moderate.

Back to the Grassroots

General election voters are typically no more impressed with such candidates than rank-and-file Republicans are. Since Ronald Reagan left office in 1989, Republicans’ average performance in the electoral vote has been to lose, 312-225. Over that roughly 30-year span, the Democrats’ average performance (winning 312 electoral votes) has beaten the Republicans’ best performance (Trump’s 304 in 2016). Meanwhile, the GOP has won the popular vote just once over that period (when George W. Bush managed 50.7% in 2004). It turns out that spending two years successfully courting Republican donors and “somewhat conservative” voters isn’t a good predictor of general election prowess.

The old adage says that “the office should seek the man, not the man the office.” Yet the current system fosters the opposite tendency, elevating the showman over the statesman. In Presidential Selection (1979), one of the best books on American politics in the past half-century, political scientist James Ceaser laments “the failure of the selection system to offer any restraint or provide a moderating influence on the pursuit and exercise of power.” Alas, the direct primary is here to stay—and it is not without its merits. The challenge, in Ceaser’s words, is how “to reestablish the political party as a restraining and moderating force on political power, but in such a way that it can pass the test of modern standards of republican legitimacy.”

Are Republicans really capable of establishing a nomination system based on reflection and choice? Or will they remain forever dependent upon accident and afterthought? None of the problems with the current nomination system can be solved by changing the order in which states vote, shrinking or expanding the calendar, or any of the other modest alterations intermittently floated. What is needed is a holistic overhaul. The new system must allow grassroots Republicans, rather than marginally conservative Upper East Side millionaires, to winnow the field. It must retain the primaries as the ultimate decider, but reinstate a meaningful convention; encourage consensus rather than mere centrism; and focus on nominating the most electable statesman who can do the job of preserving our constitutional forms and our American way of life.

In 2013, Jay Cost and I proposed in National Affairs (“A Republican Nomination Process,” summer issue) that Republicans adopt a new nomination system based on how the Constitution was ratified. Such a system would combine the best of old and new. It would empower the Republican base and in the process revitalize the party, both as an electoral force and as a Tocquevillian civil association—which would strengthen it, in turn, as an electoral force. Taking into account the changes of circumstance that have occurred over the past decade, what follows is an updated, somewhat modified, and more practical version of our proposal.

On September 17, 1787, the Constitutional Convention delegates passed a resolution asking Congress to submit their proposed charter of government “to a Convention of Delegates, chosen in each State by the People thereof” to decide its fate. In Ratifying the Constitution (1989), Allen Gillespie and Michael Lienesch write that “more than seventeen hundred delegates, chosen in town meetings and local elections by tens of thousands of voters throughout the land, came together” in their respective states “to debate the new federal government.”

Drawing upon that process, our plan calls for 3,000 delegates—an average of 60 per state and about one per county—to be chosen in town meetings and local elections by thousands if not millions of their fellow Republicans. Those 3,000 delegates, allocated based on the number of Republicans in each state and locality, would be chosen by rank-and-file Republicans and would meet at the inaugural Republican Nomination Convention. There, they would deliberate, debate, and decide which five candidates should be invited to compete for the Republican presidential nomination. A typical town of about 110,000 people would have a delegate, chosen in an election or town hall meeting conducted by a local chapter of the Republican Party. These 3,000 delegates would be supplemented by up to 600 additional delegates who would be party leaders or officials: governors, members of Congress, members of the Republican National Committee, and the like. More than 80% of the delegates would therefore be selected by their fellow citizens specifically for the purpose at hand.

A Real Contest

The convention would meet over a three-day period starting roughly five days after New Year’s. The delegates would convene and take a series of votes. During each vote, delegates would list up to five selections for their party’s nominee, with their choices ranked 1 through 5. The first choice would receive five points, the second four, on down to one point for the fifth. If a delegate listed only two people, they would receive five and four points, respectively, and no other points would be awarded. All votes from this simple and straightforward scoring system would be tallied within an hour or two, with results released publicly for the ten people with the highest scores.

The first vote would occur early on the first day. Several hours after the initial results were released, the delegates would cast a second vote in identical fashion. Those results would be released late on the first day or very early on the second. Midway through the second day, a third vote would be taken in the same manner. This time, the ten proposed candidates with the highest scores would be notified and asked to declare before the end of the second evening whether they would accept the invitation to compete for the nomination if offered. Should anyone turn down the opportunity, the eleventh-highest-scoring person would be asked, and so on. Midway through the third and final day, the delegates would cast their final and decisive votes, in the same manner as their earlier votes, from among the ten proposed candidates who had confirmed interest. The final scores would then be released, and those with the five highest scores would officially be invited to compete for the party’s nomination.

Two weeks later, those five candidates—and only those five—would participate in the first Republican presidential debate (held five months later than the first debate was held during the 2016 cycle). The five candidates would subsequently debate each other weekly until the nomination was decided. This would magnify the importance of the debates and correspondingly reduce the relevance of ads (and hence of consultants and donors). The debates would feature questions from conservative panelists: imagine, for example, a debate moderated by Brit Hume with questions posed by Ben Shapiro, Mollie Hemingway, and Victor Davis Hanson.

Based on the past two cycles, the first contest would take place in Iowa during the first week of February, following the first two debates. The New Hampshire primary would occur a week later, after a third debate. The Democrats are currently seeking to reorder the primary calendar and place South Carolina first, while President Biden has called for eliminating all caucuses—the events where citizens get most involved—on the grounds that they are “anti-worker.” The real motivation is that Biden did far worse in Iowa (fourth place) and New Hampshire (fifth place) than any prior nominee in the post-1968 era. But he won in South Carolina. It is by no means certain that Iowa and New Hampshire will be bumped from their customary spots, since Biden can’t unilaterally decree this change and faces opposition both from Democrats in those states and from their Republican-controlled state governments. For purposes of this proposal, it doesn’t really matter whether Iowa and New Hampshire go first, but voting shouldn’t start before February 1 (later would be fine).

Primary voting would decide the nominee as it does now. Delegates (selected as now) would go to the summertime, made-for-TV convention to make that choice official. The presidential nominee would pick the vice-presidential nominee from among the four other finalists for the presidential nomination—and only those four. This would restore the party’s role in ensuring that a desirable successor is waiting in the wings as necessary, thereby avoiding the kind of insider politicking that gave us Kamala Harris.

That’s how the process would play out if there weren’t an incumbent Republican president. If there were, the delegates’ first course of action would be to vote on whether to support the incumbent as the nominee. A three-fourths majority would be required—a threshold that would easily have been met by Reagan, George W. Bush, or Trump, but perhaps not by Gerald Ford or George H.W. Bush. If three-fourths support weren’t obtained, the usual process of selecting candidates would then play out with the following exception: after the results were released from the second vote on potential candidates, the delegates would vote one final time, during the morning of the second day, on the question of whether to support the incumbent. This time, a two-thirds majority would suffice to throw the weight of the convention behind the incumbent and obviate any further consideration of other candidates.

An Idea Whose Time Has Come

This proposed system would offer numerous advantages both to Republicans and to the republic:

- It would shift control to the party’s grassroots. The current system presents everyday Republicans with a field of candidates they have little to no role in determining. A choice among undesirable options isn’t much of a choice. Since “somewhat” conservatives generally swing the process, it’s crucial for grassroots Republicans to have a strong say in winnowing the field. Right now, that winnowing process is controlled by donors, consultants, and the press, none of whom share the base’s goals. Returning power to the base would help the Republican Party in almost every conceivable way, starting by generating enthusiasm among its own voters.

- It would combine the best of old and new. The old convention system encouraged deliberation and the selection of a consensus nominee that most of the party could easily get behind. This proposal would reinstitute a meaningful and dynamic convention, encourage deliberation and consensus-building, and ultimately grant invitations to five candidates with strong appeal as finalists for the nomination—while preserving the right of voters ultimately to decide the outcome.

- It would bring better candidates into the process. Strong potential candidates, including many governors, cabinet secretaries, and even workhorse members of the Senate or House, often avoid the current two-year ordeal. The new process would only be about as long as that which JFK faced, rather than spanning half an Olympiad. Distinction and advancement would come from doing well in the debates, rather than from courting an army of high-powered donors and consultants in order to sustain a lengthy primary campaign. Sure, some candidates would continue to launch campaigns—some overtly, some discreetly—in advance of the nomination convention, in hopes of landing one of the five spots. That’s fine. This process would nevertheless ensure that the party could choose among its best and brightest, rather than having only the most ambitious candidates, in combination with the richest donors, decide the finalists on behalf of the party.

- It would produce more consensus nominees. This would occur in two ways. First, the five finalists would almost certainly be more widely favored picks than the five de facto finalists who emerge under the current system, because no one could become a finalist without either being the first choice of a great many delegates or having broad appeal. Second, if it became clear that the frontrunner wasn’t a consensus choice—as in the case of Seward versus Lincoln—it would be relatively easy for voters to unite behind a second- or third-place candidate who had more consensus appeal. This would make for a marked contrast to the present system, in which a lone establishment candidate is generally left vying against several flawed, albeit more conservative, challengers.

- It would allow more voters to have a meaningful say. Not only do most voters now have essentially no say in whom they get to choose from, many don’t get to choose at all until the race is effectively over. From 1972 onward, eleven of the 13 eventual Republican nominees have won in New Hampshire, while the other two have finished second there after winning in Iowa—in which case the race was effectively decided in South Carolina. Voters in the other 47 states were basically handed a done deal. But with five candidates all having emerged from the nomination convention buoyed by that vote of confidence, Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina would probably play out more like warmups than like the main events. In relation to the current system, each of the five finalists would already have won something and therefore wouldn’t be so dependent on donors’ whims, reporters’ tales of momentum, or the verdicts of initial small states.

- It would help revitalize the party. Republicans supposedly believe in the sort of civil associations celebrated by Alexis de Tocqueville, yet they’ve let their own party stop functioning much like one. This proposal would help revitalize the party’s state and local branches, as members would be actively involved in picking delegates to represent them at the nominating convention—and perhaps would even be under consideration to be such a delegate. Such revitalization, even on the margins, would help with get-out-the-vote efforts and would be an important end in itself.

- It would save money to be redirected toward better ends. The current process costs staggering sums, as large and small donors alike open their checkbooks for well over a year before even starting to focus on beating the Democratic nominee. For all of that money, the current process typically yields a non-consensus centrist nominee who isn’t ideally suited to win the election or govern if he does.

Nothing in this proposal is infeasible. If Republicans can’t hold local elections for delegates like the founding generation could, if they can’t stage a meaningful convention like prior generations did, if they can’t have debates designed for Republican audiences and reallocate money that’s now blown on a lengthy intraparty battle to beating the Democrats—then one must ask, why not?

It’s time to redesign the Republican nomination system in a way that draws upon the process used to ratify the Constitution, reinstitutes a meaningful and deliberative convention, and preserves the right of primary voters to have the final say. In short, it’s time for the Grand Old Party to embrace a presidential nomination system of its own design, rather than continuing to use a deeply flawed system designed by and for the Left.