Books Reviewed

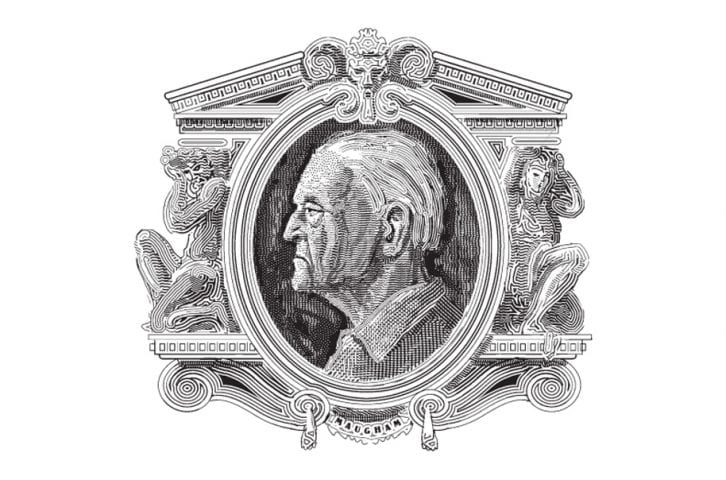

A review of The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham: A Biography , by Selina Hastings.

, by Selina Hastings.

To judge from the fate of William Somerset Maugham, a writer who wants to escape the attention of biographers cannot do worse than to ask his friends to burn his letters. Before his death in 1965, Maugham, then one of the most famous writers in the world, burned every scrap of personal correspondence he came upon and publicly entreated his friends to do the same. No fools, they ignored his requests, and the letters—several thousand of them—were tucked away to be sold later to the highest bidder.

That Maugham's letters were once a valuable commodity would puzzle most readers today. Yet he wrote some of the 20th century's most beloved novels (Of Human Bondage, Cakes and Ale), several popular light comedies for London's West End (The Circle, The Constant Wife), a fine philosophical memoir (The Summing Up), remarkably lucid and unpretentious criticism (The Writer's Notebook), and some of the best short stories in the English language ("The Alien Corn," "The Book-bag," "The Lotus Eater"). If this were not enough, Maugham was an innovator in two genres: spy fiction (Ashenden: or The British Agent) and travel writing (The Gentleman in the Parlour, On a Chinese Screen). At the height of his fame, he was required reading for nearly every aspiring writer, and influenced no less than George Orwell, Theodore Dreiser, Anthony Burgess, John Le Carré, and Gore Vidal, among others.

Of course, Maugham still has his champions, particularly (and perhaps fittingly) professional writers and literary journalists, among them Michael Dirda, Terry Teachout, and Joseph Epstein. But since his death in 1965, the main critical focus has been on Maughm's colorful and well-documented life. His feckless nephew Robin hardly waited until his uncle had been buried before scandalizing the public with tales of his sexual proclivities, while toxic friend Beverley Nichols dissected Maugham's unhappy marriage to Syrie Wellcome in a torrid 1966 memoir, A Case of Human Bondage. More disinterested biographies have appeared. The latest offering, The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham is by Selina Hastings, a British journalist who has made something of a cottage industry out of Maugham's bookish coterie, having published well-reviewed lives of Nancy Mitford, Rosamond Lehmann, and Evelyn Waugh.

This is rather select company, but even by such high standards of lives fully lived, The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham does not disappoint. For sheer worldly glamor, Maugham's story can't be beat. His was a life of fabulous personal wealth, international celebrity, and globe-trotting through exotic locales. There's ample romance in just the names of the people and places he frequented and wrote about: Ceylon, Noël Coward, Siam, Grace Kelly, Shanghai, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, the Windsors. And the list goes on. As the diarist Chips Channon enviously observed, Maugham "has been everywhere, met everybody, tasted everything."

* * *

Maugham's epicurean life began in 1874 in a prosperous English household on the Champs-Élysées. His father, Robert, was a respected solicitor who handled the British Embassy's business, and his mother, Edith, a beautiful young socialite who had grown up in India. Maugham was the youngest of four brothers, but they had been sent away to English boarding schools, so he was raised as a much loved and much indulged only child.

This happy beginning soon came to an end. When Maugham was eight years old, Edith suddenly succumbed to tuberculosis, and Robert died two years later of stomach cancer. "Few misfortunes can befall a boy which bring worse consequences than to have a really affectionate mother," he would ruefully remark in one of his notebooks. The loss of his mother was the defining tragedy of his life, and it was during this period of intense grief that Maugham developed his famous stammer.

The orphaned boy was sent to England to live with his uncle, the vicar of Whitstable, and his wife. Long childless, the couple was ill-suited to caring for their shy, sensitive charge—particularly Maugham's uncle, whom he would skewer in his autobiographical novel, Of Human Bondage (1915), as "a weak and selfish man whose chief desire was to be saved trouble." A lackluster student, Maugham was soon able to convince his uncle to allow him to leave school to study German in Heidelberg, and from that time on, at age 16, he was his own master.

His brief time in Germany inspired a life-long wanderlust, but having only a small allowance he needed work first. He decided to train as a doctor at St. Thomas's Hospital in London, with the hope he could find a place on a ship. It would prove a turning point in his life. "I learned pretty well everything I know about human nature in the five years I spent at St Thomas's Hospital," Maugham recalled, and it was his harrowing experience tending to patients in the slums that gave him the subject for his first novel, the Zolaesque Liza Of Lambeth (1897), published when he was just 23. The book was a modest success, enabling him to travel to Spain, Italy, and France.

For ten years, Maugham struggled to establish himself as a writer. Then, in 1907, the Royal Court Theater accepted Lady Frederick, a lively drawing room comedy, as a last-minute stop-gap, and overnight he became a celebrated dramatist. Ever practical, he cashed in on his newfound fame by turning out a play almost every month. (As a rule, it took him a week to write an act, with a week to revise the whole.) By 1908, he had four plays running on the West End—a feat unmatched by any living playwright.

"I have never quite got over my astonishment at being a writer," Maugham wrote in The Summing Up (1938). "There seems no reason for my having become one except an irresistible inclination." This inclination kept him writing for over 60 years—throughout his famous travels in the Far East, his work as a spy during the world wars, a brief dalliance in Hollywood, countless unrequited love affairs, and a disastrous marriage and divorce, which Hastings calls, without exaggeration, "the longest, most miserable and most bitterly destructive relationship of his life." He made over a million dollars in royalties from just one short story, "Rain" (1921), enlarging a fortune that secured him a life of luxury and ease at his beloved Villa Mauresque on the French Riviera. He worked in numerous genres and was an acknowledged master in three during his lifetime, as novelist, playwright, and short-story writer. At the end of his life, he counted himself the author of almost 70 works: 31 plays, 19 novels, six volumes of short stories, four memoirs, and eight nonfiction works.

* * *

For all Maugham's incredible success, however, the story Hastings tells is a deeply sad one. At one point, she compares her subject to King Midas, the man with the golden touch who nonetheless gained nothing of value. "Every one of the few people who have ever got to know me well has ended up by hating me," Maugham wrote near the end of his life. Hastings titles this sordid last chapter, "Betrayal," and Maugham appears as much the betrayer as the betrayed. His nephew (and surrogate son) blackmailed him out of $500,000. Under the sway of his personal secretary and lover, Alan Searle, Maugham published a vindictive and ill-advised memoir, Looking Back (1962), about his life with Syrie, losing him the few friends he had left. ("A senile and scandalous work," Graham Greene called it.) He managed finally to estrange himself even from his loyal daughter, Liza, in a degrading battle over her inheritance. Publicly disgraced and despised, Maugham, on his deathbed, is said to have asked the philosopher A.J. Ayer to visit and reassure him there was no afterlife.

Hastings captures well both the glamour and the shabbiness of Maugham's life—not a small achievement. Like her subject, she enjoys entertaining yarns and gossip—for example, Maugham's introduction to Frank Sinatra. "Frank says, ‘Hiya, baby,' and Maugham replies, ‘Very well, indeed, but hardly a b-baby.'" Hastings also boasts a more serious purpose: to rehabilitate Maugham's literary reputation. At this, she is less successful, relying on plot summary in place of interpretation or close reading. To the critics' charges that Maugham's writing is commercial, middlebrow, superficial, and brittle, she musters little in the way of defense, settling for a less exalted place in the literary pantheon: "Somerset Maugham, the great teller of tales."

In fairness, Maugham is not much help. Never a critic's darling, he adopted an air of "humorous resignation" to his reviews, famously placing himself "in the very front row of the second rate." He openly deprecated his limited powers of imagination, the sparseness of his prose, his lack of originality. Having once been poor, he was not only vulgar enough to admit to writing for money (a cardinal sin among his silver-spoon, Bloomsbury contemporaries), he was spectacularly successful at it. Worse still, he made no pretense of despising his vast audience. Instead, he avowed the most terrible of middlebrow heresies, that books are, first and foremost, not for critics or other writers, but for readers. As such, he insisted that an author had a duty to those readers—to give them pleasure. Literature can edify and inform, but it must first aim to please: "Literature is an art. It is not philosophy, it is not science, it is not social economy, it is not politics; it is an art. And art is for delight."

For his defense of pleasure and commercial success, Maugham was dismissed as a mere entertainer, shamelessly pandering to the public taste. (Edmund Wilson, while admitting he had read little of Maugham's work, famously denounced him in the New Yorker as "a half-trashy novelist who writes badly, but is patronized by half-serious readers, who do not care much about writing.") Maugham was unabashed about his desire to entertain, reminding his critics that such pleasure need not be unintelligent. "To a healthy understanding there is nothing disagreeable in the activity of the intellect," he wrote. "One of the signs of culture is that you are able to extract pleasure from objects or events to which the ignorant are indifferent." He was himself a man of erudition, whose idea of an enjoyable afternoon was to translate a play by Shakespeare into German. How many highbrows—then or now—could, as he did, speak Spanish, Italian, and Russian, in addition to French, German, and English?

Where he parted ways with them was in his belief that "ordinary people are as capable of enjoying great music, great paintings, and great literature as those others who have had ampler opportunities to form their taste and confirm their judgment." To that end, he compiled several anthologies and critical works celebrating his favorite authors: Maupassant, Chekhov, Conrad, Dickens, and Kipling, among others. As should be obvious from such a list, Maugham, while prizing unfashionable "readability" in his criticism, did not depreciate style or technique. It is "wholly comprehensible," he wrote, that critics would be most interested in stylistic innovations, like the new stream of consciousness, since they offered "a sort of freshness to well-worn material and were a fruitful matter of discussion." What he warned against was allowing style to become an end in itself, where "willful obscurity" masquerades as "aristocratic exclusiveness." Above all, he reminded his avant-garde contemporaries that "a work becomes a classic only because succeeding generations of people, ordinary readers…have found delight in reading it. It affords that because it appeals to the human emotions common to all of us and treats of the human problems that we are all confronted with."

* * *

Indeed, there is much to delight from in Maugham's expert craftsmanship, tight plotting, decisive endings, clarity of style, and economical, closely motivated characterization. If his criticism encouraged respect for the common reader, his fiction grappled with what he called "the infinite contrariety and the disordered richness of man." The two are related. As a young doctor and then a world traveler, Maugham compared himself to a naturalist "who comes into a country where the fauna are of an unimaginable variety." In listening to others' stories, he learned that even the most ordinary people are rarely "all of a piece," and will more often than not confound one's expectations.

How can the discordant elements of human nature nonetheless yield a "plausible harmony"? This is the question all his fiction seeks to unravel. His stories are mysteries of character, following the protagonist as he or she is about to commit an extreme and unexpected act. Each presents the reader with a conundrum: What drives this person? Who is he really? Why, in "The Lion's Skin" (1938), does Robert Forestier, a Mayfair car-washer living in disguise as an English gentlemen, run into a burning house to rescue his wife's dog? Why does Philip, the unhappy hero of Of Human Bondage, persist in his destructive attachment to the cruelly indifferent Mildred? Not for nothing was Maugham considered the inventor of the modern spy story, inspiring the works of Ian Fleming, Graham Greene, and John le Carré. His works are psychological thrillers, focused less on the glamour and adventure of espionage (in reality, "extremely monotonous") than on the darker corners of the human heart. The main drama of "The Traitor" (1928) is not the capture of the English turncoat, Grantley Caypor, but the ambivalence the British agent Ashenden feels towards the jovial, unwitting villain. How can such a good-natured man commit such cruel and treacherous acts? he wonders. "Was Caypor a good man who loved evil or a bad man who loved good? And how could such unreconcilable elements exist side by side and in harmony within the same heart?"

Maugham rightly offers no direct answers to these questions—evidence again of his high opinion of his readers. His critics might accuse him of placing plot above characterization, of caring only for externals, but he trusted his readers to come to their own conclusions. He recognized, as Anthony Daniels noted in the New Criterion, that it is far more effective to have the reader imagine a character's psychological state than to describe it explicitly.

Hastings argues that we are overdue for a Maugham revival, and she may be right. His plays are back in production. Drama critic Terry Teachout wrote the libretto for an opera based on his short story "The Letter." He remains the most filmed of all fiction writers, surpassing Sir Athur Conan Doyle for number of screen adaptations. Even high-brow types, like Pico Iyer who recently edited a volume of Maugham's travel writing, are beginning to rediscover his prose.

If readers flocked to Maugham (and may do so again), perhaps it is because he evinces a real respect for them in both his fiction and his criticism. Against the prevailing fashion of the day, he affirmed the universality of art, while still insisting on high standards. "I think a bookcase that held twenty books would be large enough to contain all the works of fiction that it would leave a man spiritually poorer not to have read," he once declared. (In that light, Maugham's claim to be in the very front row of the second rate no longer seems so modest.) Even lesser writers should strive to offer their readers "excellence of style, an insight into the multiplicity of human nature, and here and there food for reflection." And that is just what Maugham, at his best, provided.