Books Reviewed

A review of Jews and Power, by Ruth R. Wisse

Clear your mind of cant." has anyone who writes today about the political dimension of Jewish experience ever taken this motto of Samuel Johnson's to heart more than Ruth Wisse? Has any contemporary voice laid siege more effectively to the barricades of stale cliché and bad logic that obscure the "Jewish problem"?

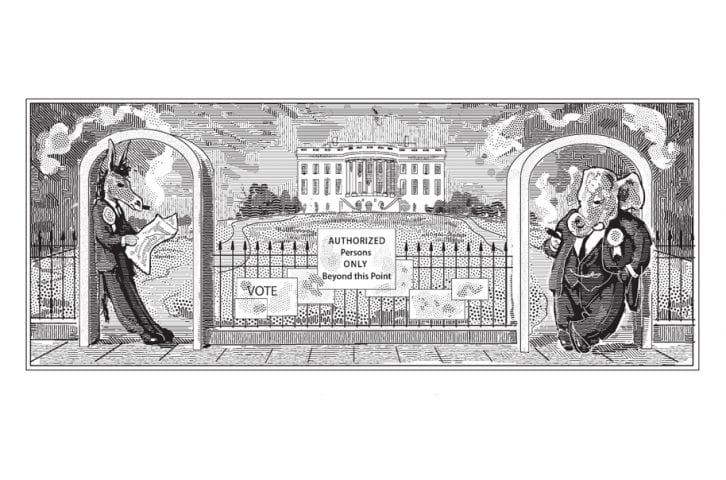

You may have heard that Jews are an intransigent minority responsible for Communism in capitalist countries, capitalism in Communist countries, cosmopolitanism in nationalistic countries, and, in the minds of "realist" foreign-policy experts, every evil on the globe except avian flu. In fact, Wisse shows, the Jewish problem is really the problem of nations that must blame their dysfunction on Jews. Perhaps you have been told that Jews are too powerful ("98% control," according to Noam Chomsky). On the contrary, "in the real world, Jews have too little power and influence…[and] too little self-confidence about defending themselves." Do you believe, as did isolationist foes of American entry into World War II or the current war against terror, that Franklin D. Roosevelt and George W. Bush caved in to Jewish demands that damaged genuine American interests? On the contrary, these leaders went to war not to save Jews but to defeat Nazism and Islamic fascism, which also (not accidentally) were anti-Jewish. Do you believe that the creation of Israel solved the problem of the Jews' relation to political power? You are mistaken: the permanent state of siege in which the Jewish state exists reproduces the constant burden of peril and political imbalance of the Diaspora. Do you think that moral superiority over their enemies is the chief desideratum for Jews, as when Golda Meir told Egypt's Anwar Sadat she could forgive him for killing "our sons" but not for "making us kill yours"? Think again, urges Wisse: remember that your enemies' designs upon you are a more urgent concern than your children's decency. To be decent, you need to be alive.

Although Wisse has spent her professional life as a teacher and scholar of Yiddish literature and language at Harvard, she approaches these questions without the prejudices common among her colleagues. In 1954 Irving Howe praised Yiddish literature and the culture it reflected for the very characteristics that made the opposing camp of secular Jews, the Zionists, spurn it: "The virtue of powerlessness, the power of helplessness, the company of the dispossessed, the sanctity of the insulted and the injured…." Though in later years Howe and Wisse became friends and literary collaborators, he strongly disapproved of her forays into political writing and considered her view of Jewish history and politics incompatible with Yiddish tradition.

Wisse has always taken a very different view. In Jews and Power, she argues that when Jews were vanquished and sent into exile from their homeland they decided (unlike other conquered peoples of the ancient Near East-Jebusites, Hittites, Girgashites) to remain faithful to their God and covenant; they were convinced that they had been exiled because of their sins and not because their God had proved powerless to protect them. Jews recognized that the price of such loyalty might be poverty and powerlessness, yet this was a price they were willing to pay. "But," insists Wisse, "when Jews then take that a step further and say that to be a Jew is to be weak and powerless—this is…romanticization, because Jews never wanted to be weak or poor. And until recently they certainly never made a virtue of it."

Glorification of powerlessness, she contends, is in fact antithetical to Judaism. Powerlessness does worse than corrupt, it eliminates: prior to Constantine's establishment of Christianity, Christianity and Judaism had almost equal numbers in Europe. The tendency to romanticize powerlessness and an abnormal political existence ought to have come to an end during World War I, when "an estimated half million Jews fought in the uniforms of the vying armies of Europe with no one to prevent the violence directed at them." For Wisse, the crucial link between the study of Yiddish literature and the study of Jewish politics is that the "Yiddish language, developed by European Jews over almost a thousand years, was practically erased along with them in a mere six, 1939-45. So studying Yiddish literature…concentrates the mind on Jewish political disabilities."

* * *

Jews and Power is a short but ambitious book, a critical history of the Jews' problematic relation to power from 70 C.E. through the Oslo Accords and their catastrophic aftermath. The prologue presents the book's defining anecdote, an incident in occupied Warsaw in 1939. After Nazi soldiers harassed a Jewish child, his mother picked up the bruised little boy and said: "Come inside the courtyard and za a mentsh." The mother was telling her son, in a well-known Yiddish expression, to become a decent human being. Although that term conveyed to many Yiddish-speaking Jews the essence of "Jewishness," and Wisse herself was taught to revere it in her Montreal Jewish school, she now calls it into question. For she had also learned from her school's principal what had happened to Jewish children in Europe. "If each of you," he told the children, "was to take a notebook and write on every line of every page the name of a different child, and if we collected all your notebooks, it still would not equal the number of Jewish boys and girls who were murdered by the Germans." The little boy in Warsaw could not have done as his mother urged, Wisse concludes, "because becoming fully human presupposed staying alive." An injunction to behave decently that disregards your enemy's intention to remove you from the world is "moral solipsism," a peculiarly Jewish affliction that Wisse in an earlier book defined as "the Jewish moral strut."

The book disputes the commonplace that Jewish politics ended when Jews left their ancient homeland. In fact, Wisse argues, they were just as politically active outside the land of Israel, despite the fact that in the Diaspora they were a nation without nationhood, land, central government, or means of self-defense, a people denied the dignity of being a people. But the abiding centrality of Jerusalem and of Hebrew in Jewish worship made them a dispersed rather than a dismembered people. Jews in the Diaspora tried to retain control over their national destiny by accepting responsibility for political failure. They devised a strategy of accommodation to defeat, and dependency on local rulers for protection. Jewish life outside of the ancient homeland would be determined by the best bargain that Jews could strike with Gentile rulers. It afforded them temporary advantages, but the greater the benefits Jews derived from those in power, the greater the power rulers had over them. When necessary, their erstwhile protectors would sacrifice them to mob violence. The longer Jews remained in exile, the more they acquired the reputation of being easy prey.

Emancipation in Europe had its unanticipated perils. Modern Jews were disappointed to find that the replacement of one-man autocracies and systems of state censorship by elected assemblies, the popular press, and other democratic institutions actually reduced Jewish influence and left them in many respects worse off than before. With kings toppled from their thrones, the new Hamans appealed to the citizenry, often with great success. Old-fashioned religious Jew-hatred evolved into "anti-Semitism," a term invented in 1879 by the German agitator Wilhelm Marr to distinguish the old hatred from its new manifestation grounded in race theory. Anti-Semitism, according to Sir Jonathan Sacks, Britain's current chief rabbi, "exists…whenever two contradictory factors appear in combination: the belief that Jews are so powerful that they are responsible for the evils of the world, and the knowledge that they are so powerless that they can be attacked with impunity."

This combination of an enormous image (Christ-killers, bloated plutocrats, Zionist imperialists), with almost no political power proved irresistible to a new legion of predators. Anti-Semites called the Jews' talent for successful accommodation to unfavorable political circumstances a quest for domination. "The diabolical element in this accusation," observes Wisse, "was to have charged the Jews with seizing the political power they were unwilling to wield. Marr's attack on the Jews would succeed precisely because they lacked the will to political power of which he accused them." By the end of the 19th century the new anti-Semitism, culminating in the Dreyfus Affair, the dress rehearsal for the Nazi movement, had become "the most effective political ideology in Europe." It provided European politicians with a simple explanation for whatever was going wrong: revolution, psychoanalysis, pornography, moral turpitude. This pan-European campaign against the Jews as the cause of all misfortunes foreshadowed in several ways today's "new anti-Semitism" that fixates on Israel, not least in employing the scam which claims that Jewish responses to the campaign of defamation are proof of just how much power Jews do wield and how they use it to "stifle" all "criticism" of Israel.

Although Wisse does not explicitly reproach Jews for the political strategy they adopted during centuries of exile, she insists that by the end of the 19th century it was clear that they needed an alternative to a failing strategy. This alternative was Zionism, which even the sour Hannah Arendt called the "only political answer Jews have ever found to anti-Semitism and the only ideology in which they have ever taken seriously a hostility that would place them in the center of world events." The "Return to Zion" represented both a break with the old politics of adaptation and a continuation of it; a belated recognition of the need for self-defense and a persisting Jewish inability to see themselves through the eyes of their enemies; a rescue of the Jews from their status as a pariah people and a discovery that the pariah people has become the pariah nation. "Not until [Ze'ev] Jabotinsky thought of organizing Jewish military units in the British army," she writes, "did Zionist leadership begin to consider the possibility of a Jewish armed force that would fight under its own insignia and flag." Again the repudiation of "Yiddish" wisdom was required to see the obvious. Jabotinsky wrote that "this very normal idea [i.e., self-defense] would have occurred…to any normal person." The last phrase, rendered in colloquial usage by the Yiddish goyishe kop, expressed Jabotinsky's wish that Jews, forever preening themselves on their supposed cleverness, would become as commonsensical as the rest of the world.

* * *

But even those Zionist leaders who managed to acquire something of a goyishe kop, like Jabotinsky and David Ben-Gurion, could not foresee that the Arab and Muslim countries would make anti-Zionism into a way of life, and the Palestinian Arabs into a kind of anti-nation deriving their entire meaning and purpose from the goal of destroying Israel. Nor did they foresee that the Diaspora strategy of accommodation could take its deadliest form in Zion itself, in the strategy of yielding contiguous territory to enemies dedicated to Israel's destruction, financing and arming their forces in the hope of conciliating them and gaining security. No goyishe kop in the history of nations had ever come up with such a clever idea, the ultimate expression of "moral solipsism." Obviously the creation of Israel has not solved the problem of the Jews' relation to political power. Truly to be moral, Wisse argues, modern Jews, who are largely without faith in the power of the Almighty, must themselves supply the missing dimension of power; otherwise, they sign a suicide pact with each new enemy that comes along.

Wisse concludes by returning to a theme adumbrated in her introduction: the question of why Jews have figured and still figure so prominently in the politics of regimes that also threaten the rest of the world: Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, Iran, and the multitudinous troops of Islamic fascism. Although this is more bad news, it does have a positive dimension: namely, that the Jews' new political status, achieved by the existence of a Jewish state, has given them a new role as an ally, with something to offer America and the other democracies. She believes that America, at least, is learning the lesson that "thugs who get away with harassing Jewish citizens go on to torch the rest of the citizenry." Jews and Power is a powerful salvo in the war of ideas over the Jewish state, a war that Israel has been losing almost as steadily as she has, until recently, been winning on the battlefield.