Books Reviewed

If you like Wal-Mart, you might just love Steven Malanga’s The New New Left. If political principle or social snobbery leads you to shun that cornucopia of consumer bargains, then you will probably put down this short, well-written book rather quickly. Its premise is that competitive markets, low taxes, and entrepreneurial spirit are far better at lifting people out of poverty than are government programs, however well intentioned. For Malanga, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, Wal-Mart exemplifies the wonders of capitalism; and the Left’s attack on it illustrates the cynicism of those who speak of social justice but deny the poor an opportunity to save money, find entry-level jobs, and revitalize their neighborhoods.

Malanga constructs a series of appealing stories around this central narrative line, but he is unlikely to convince those not already converted. He simply doesn’t provide much evidence to support his premise, although he does offer some telling glimpses of the New York City Council’s buffoonery, the modern university’s intellectual corruption, organized interests’ disturbing influence in politics, and the decline of local political parties.

Like most journalists, Malanga is inclined toward a Manichean view of the political world. Typically, journalists assume that greedy corporate executives are in cahoots with cynical politicians, and that brave correspondents must uncover the truth to protect the little guy. For Malanga, however, power-hungry union leaders are in cahoots with cynical politicians, and brave correspondents must uncover the truth to protect taxpayers and business entrepreneurs. “Politics in America today,” he holds, is a “faceoff” between taxpayers and “tax eaters.” He warns that “the vast expansion of the public sector is finally reaching a tipping point, giving tax eaters the upper hand, especially in America’s cities.”

The most prominent element of the “tax eater” coalition—the one to which Malanga devotes most attention—is the government-employee union. Nearly as important but often overlooked by journalists and political scientists are the “social services groups created by the War on Poverty” with their ever-growing number of “quasi-public workers.” He notes that health care jobs, for instance, have grown from less than 4% of the work force in 1965 to almost 10% today. Most of the funding comes from Medicare, Medicaid, and highly regulated insurance plans.

Malanga argues that the venal motives of public-employee union and social service group leaders are cleverly disguised by another member of the “new new left,” political activists with cushy university jobs. He may exaggerate the influence of those individuals (one hesitates to call them academics) working in “labor studies” programs in public universities, yet the stories he tells show how deeply some institutions of higher learning have sunk into the swamp of unabashed partisanship.

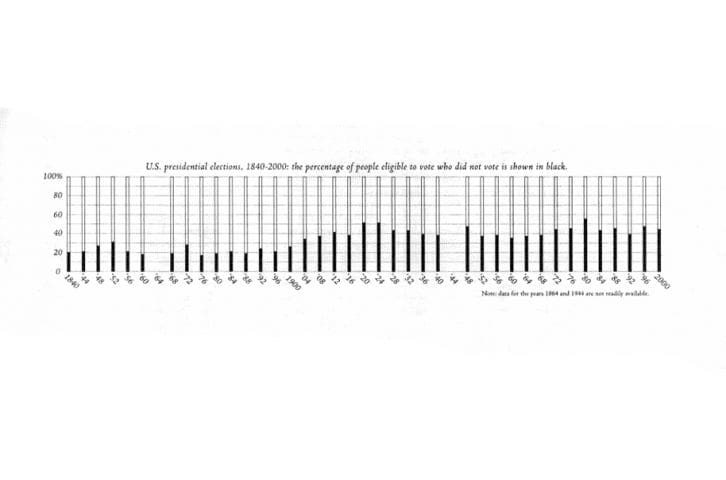

At a time when we are bombarded with newspaper articles and expert analysis about the overwhelming power of conservatives, businessmen, and the Religious Right, it is useful to be reminded that the welfare state’s supporters continue to wield substantial political clout. This helps explain why a quarter of a century after the Reagan Revolution, and a decade since the Gingrich Revolution, the public sector is bigger than ever. Although many beneficiaries of government programs are not organized, those who provide government services are. Not only do they vote, but they can help mobilize all those beneficiaries who would be threatened by retrenchment of the welfare state.

Occasionally, Malanga’s description of the new New Left’s power is marred by his astonishment that it at times employs the very tactics corporate executives use to slip loopholes into the tax code. For example, he decries the success of the Association of Community Organizers for Reform Now (ACORN) in putting a “living wage” question on the ballot in Detroit before the business community had understood its significance. This is clever politics, not dirty tricks. GM and Ford should have enough political smarts to cope with such things.

More telling is Malanga’s point that the new New Left’s influence has grown at the state and local level at the same time that it has declined at the national level. An odd but crucial feature of American government over the past 50 years is that the number of federal civilian employees has remained constant despite the enormous expansion of the federal government’s role. This is because most federal programs are carried out by state and local employees, whose numbers have grown by leaps and bounds since the 1960s. This peculiarity of our government bureaucracy reduces the power of public-employee unions at the national level, but magnifies it at the state and local level.

Malanga warns that the “tax eaters” will demand more and more of the golden goose known as the taxpayer, especially in cities like New York and San Francisco. Here it is useful to remember that anything that “can’t go on like this forever” won’t. From the perspective of a New York City resident (like Malanga), the gravest danger is that the new New Left will drive productive businesses (i.e., employers) out of the Big Apple. But this exit option, a vital part of our federal system, is precisely what puts the brakes on the expansion of state and local governments. Federalism both creates pockets of political support for big government, and limits the ability of these regions to finance their projects.

* * *

One of the best chapters in the book is Malanga’s critique of Richard Florida’s popular book, The Rise of the Creative Class (2002). Florida argued that cities prosper not by keeping their tax rates low to please business leaders, but by investing in amenities (theaters, bike trails, extensive social services) and by encouraging social tolerance and diversity to attract a highly educated workforce. According to Malanga, this political “equivalent of an eat-all-you-want-and-still-lose-weight diet” offered the new New Left a “way to talk economic-development talk while walking the familiar big-spending walk.” He shows that during the 1990s “creative” cities like New York, San Francisco, Austin, and San Diego barely managed to keep up with the national average in job creation—despite the fact that they were among the major beneficiaries of the high-tech bubble. Once the bubble burst, Richard Florida’s supposed “talent magnets” began to lose not just jobs, but population.

The idea that public projects such as highways, schools, and even museums attract employers and highly trained employees is hardly a crazy one. One of federalism’s greatest advantages is that states and cities can offer a variety of services and tax packages. They can experiment; they can find a mix that reflects voters’ preferences. (Malanga reports that the capital of Texas adopted the economic development theme “Keep Austin Weird.”) Competitive federalism will not work, though, if the competing units can persuade higher levels of government to subsidize their endeavors. Not only does this hide the cost of providing public services, but it leads everyone else to demand the same subsidy—lest citizens get stuck paying the bill without receiving anything in return.

Competitive pressures—often misleadingly called the “race to the bottom”—place severe limits on the new New Left’s influence. That is why the coalition described by Malanga searches so assiduously for ways to export the costs of its initiatives. He notes that New York City’s “living wage” ordinance “zeroed in on health-care workers because many of them worked in state-funded programs.” Similarly, Detroit’s living wage law applied to “contracts that the city simply administered but that were paid for by federal agencies.” The new New Left’s adversaries at the state and national level have an opportunity to thwart these efforts—provided they understand what is at stake.

One local issue surprisingly absent from Malanga’s story is education, which is in many respects the preeminent civil rights issue of our time. This may be the policy area in which government-employee unions are strongest—and the divergence between the interests of the unions and disadvantaged residents of large cities most substantial. Many cities clearly are doing a terrible job of educating poor minority children. All too often teachers’ unions have stood in the way of experimentation and reform. The Manhattan Institute has played a prominent role in calling attention to this problem and identifying unorthodox solutions. Given Malanga’s journalistic talents and knowledge of New York politics, this would be an apt topic for his next exposé.