Books Reviewed

Is Conservatism compatible with capitalism? Theorists such as Joseph Schumpeter thought (as did Marx) that the central process of capitalism was “creative destruction.” Too much destruction, and there isn’t much left to conserve. The conclusion would have to be that capitalism drives out conservatism, but for the last half century, America has been developing a dramatic refutation of this abstract thesis.

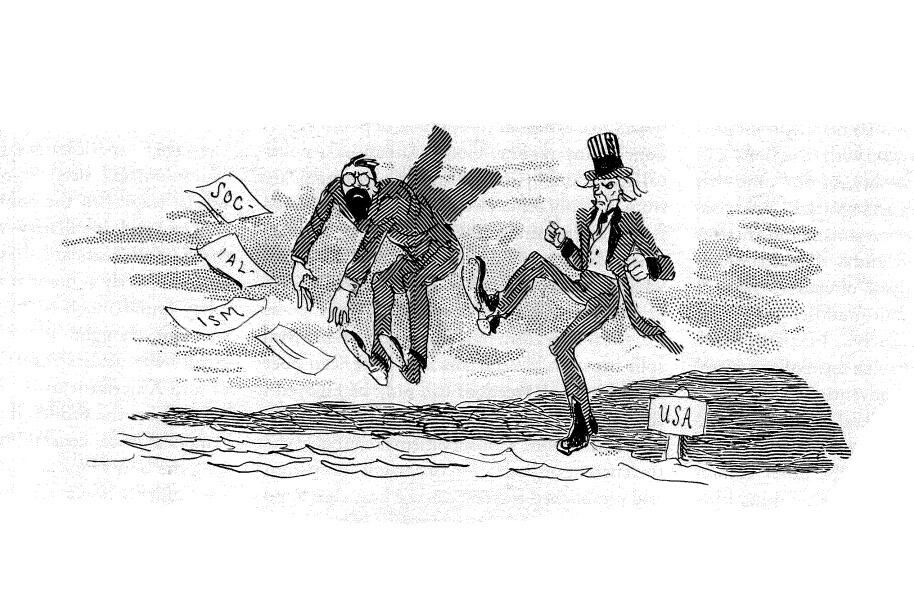

It is a development that would have astonished students of American culture in the middle of the 20th century. In those days, Louis Hartz declared that America was a liberal society lacking both conservatism and socialism because it had no aristocracy to sustain conservatives, and no real working class to play the role of a Marxist proletariat. Political scientists regarded American political parties as relatively loose alliances of political convenience, substituting rhetorical flourishes for ideological conviction. Democrats were constrained by Southern conservatives, and Republicans had “Rockefeller Republicans” to demonstrate that they weren’t just a gang of plutocrats. The result was that up until the 1960s, anything recognizable as “conservative” in the United States exhibited either eccentric Tory nostalgia or took the form of a few rather paranoid fringe groups who might make the odd splash (like McCarthyism) until the basic liberal common sense of the American tradition slapped them down.

Yet in the last half century, America has undergone a regime change that is analyzed in The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge, two British journalists working for The Economist. Like all political movements, conservative America needs a legend about its origins, and the authors have given a splendidly lively account of it. The legend begins with disaster, in the form of “the conservative rout” from 1952 to 1964, culminating in the disastrous presidential bid made by Barry Goldwater in 1964. Similar genesis accounts can be found in related political movements—that of the Mount Pelerin Society, for example, which begins with F.A. Hayek calling together a saving remnant of free-market liberals in 1947, or Margaret Thatcher’s conversion to the free market and her involvement with the London Institute of Economic Affairs after 1976. Few things are more inspiring than triumph arising from times of pure despair.

It is no small part of the flavor of these stories that the triumphs they celebrate confounded a complacent mistake among their opponents, namely, that the world was moving inexorably towards a sane and moral consensus that would leave the anachronism of conservatism behind. As Micklethwait and Wooldridge tell us, Columbia University’s famous Richard Hofstadter, who had written about the “paranoid style” of politics in America, was reduced to rhetorical spluttering by the Goldwater candidacy: “When, in all our history, has anyone with ideas so bizarre, so archaic, so self-confounding, so remote from the basic American consensus, ever got so far?” Many American coastal dwellers still feel pretty much the same way (as do the vast majority of Europeans), and they focus their antipathy on George W. Bush.

The authors have a terrific story to tell, and they tell it with immense verve and wit. This is journalism with pace, covering a lot of Tocquevillian territory, even if it is Tocqueville lite. I can forgive anything in a book so sensitive to the witty froth of politics, and I don’t think that heavy lashings of empirical political science would have added a great deal to our understanding. Two points seem to me worth looking at in a little detail. The first is to ask what we might mean by calling the diverse political enthusiasms that have transformed American life “conservative,” and the second is to observe how much this book reveals to a British reader about the way in which America has become a civilization fundamentally distinct from its European roots.

* * *

The very term “conservatism” has a timid sound about it, as Hayek once argued in explaining why he rejected it. Few countries outside Britain and Canada have parties proclaiming themselves “conservative” and the American triumph, of course, flew the flag of the Republican Party. It is odd, however, that a name so redolent of passive obedience to the past should have become so explicitly the dominant doctrine of such a dynamic capitalism as that of the United States. The basic point, no doubt, is that countries with conservative regimes are in fact more enterprising and dynamic than countries that make a fuss about their revolutionary credentials, just as any country that has the word “democratic” in its title can be confidently marked down as a corrupt autocracy. The conservative British at the end of the 18th century were creating a whole new industrial civilization at a time when the revolutionaries in France were merely churning society and succumbing to military adventurism. So there is no problem about associating conservatism with dynamism, but the name itself remains odd.

The explanation might be found in the other “dimensional” term in the title of the book: the “right” nation. To be “right-wing” is to be identified by contrast with “the Left,” but it is a feature of the rhetoric of our time that “the Right” suffers the ambiguity of being associated both with libertarianism and the free market on the one hand, and with fascist movements on the other. Again, of course, the reality belies this popular but muddled judgment: collectivist movements such as Nazism (which explicitly pronounced itself a form of socialism) are essentially left-wing adventures in managerialism. Yet in much of liberal America, “right-wing” is associated with brutal indifference to human suffering. This was the point George W. Bush was repudiating in proclaiming himself a “compassionate conservative.”

There was thus in the mood music of the conservative movement an element of defiance, of cutting against the grain, of reclaiming a besmirched vocabulary from undeserved disdain. What could better tweak the noses of the pompous Left than setting up branches of the Second Amendment Sisters (in favor of guns) at women’s colleges, or protesting to the university authorities that left-wing professors were cancelling classes to go on anti-war protests? In modern culture, a posture of oppositionality is an affectation even of the most established elites, and the conservatives did not hesitate to exploit it. They had to face down most of the media. They had to face down the universities dominated by complacent progressives. And they had to face down Hollywood. But they had in their favor the one move that in America can be a decisive trump: patriotism. Conservatives were not only happy in their skins; they were happy in their country. They were able to strike out at a kind of false consciousness. “It is not possible to have a debate, a discussion with someone who at their root…hates everything this country stands for” as one enthusiast put it, “but doesn’t hate it enough to leave.” Many liberals were thus hoist by the old embarrassment that Communists and champagne socialists could never avoid: hypocrisy.

The “right nation” came to dominate the United States from a remarkable confluence of different movements and enthusiasms: evangelical Christians exercised by the abortion issue, libertarian exponents of tax-cutting, intellectuals disillusioned with Marxism (and some influenced by Leo Strauss and Ayn Rand), Southern conservatives dedicated to states rights, and a miscellany of people alienated by the wilder shores of 1960s’ liberation movements. All very difficult to hold together, and nearly all of it couched in the idiom of revivalism.

* * *

It is unimaginably distant from the conservative temperament advanced by such thinkers as Edmund Burke, which is in fact one essential component of political wisdom in any regime. Conservatism as a political attitude only makes sense as distinguished from the only other two genuinely political doctrines: liberalism, which insists on the primacy of freedom in modern states, and socialism, which revolves around the needs and interests of (in various senses of the word) “the poor.” Classical liberalism has, since John Stuart Mill, split between libertarians and American liberals, who think freedom can only be enjoyed if the state provides the supposed necessities for “self-realization.” Conservatism is the belief that the current organization of society, its customs and established interests, is the best clue to political reality, and that this living form of life should be disturbed by abstract ideals only in the most exceptional circumstances. Whereas American liberals and socialists live in a state of continuous excitement about problems to be solved by governmental action, conservative statesmen generally recommend the patience to allow problems to be “solved” (if solved they ever can be) by the more or less spontaneous responses of the people themselves. The supply of universal schooling in Britain and America, for example, came from churches and communities who valued education; it was only later that governments found reasons for taking it over, and in many respects, political intervention led to widespread decline. That is one of the reasons why the growth of the free-schooling movement is far from the least interesting among the episodes in the book.

Not much in conservatism, then, to fire the blood and stiffen the sinews. Enthusiasm generally makes the conservative heart sink. Yet the story of The Right Nation is that of a vast outpouring of enthusiasm. Where in all this can we find anything that might be called “conservative”? It comes, let me suggest, in the negative or skeptical side of the enthusiasm. Libertarians are skeptical of the wisdom of governments, intellectuals mistrust experts and judges, while the religious are easily persuaded that the latest scientific fad need not be regarded as truth itself. Again, conservatism is above all a movement concerned to trust the people—not necessarily on the basis of voting, but on the basis of how they actually live their lives, under law. The conservative tradition often may also incorporate an element of faith: faith particularly in inherited standards and beliefs, an element supplied in abundance by social conservatives and evangelical Christians. Add to this a touch of juvenile deviltry, a passion épater les bourgeois and you have something rich, strong, and virtually indefinable.

The emergence of this conservative movement over the last fifty years has a remarkable, and not entirely agreeable, flavor that will strike any foreign reader of The Right Nation. We all knew that America was different, that God and Mammon had been accommodated there in special ways. But the dominance of American culture, and familiarity with California and the Eastern seaboard, has long made foreigners feel entirely at home with the United States. They found much to admire, and even what was not thought admirable—the food, the guns—was at least exotic. The sudden burst of anti-Americanism in Europe over the Iraq war reflects the sudden discovery that “the real America” is not coastal but continental. Texas, long the butt of jokes about American absurdity, suddenly turns out to be direly typical.

The odd cause of European disillusion with America is that Europe itself has come to be dominated by a strange salvationist faith—even a kind of “fundamentalism,” though one that cannot speak its name. It is a faith largely shared with the liberalism of coastal America, and it is secular and internationalist. The internationalism has developed into a worship of transnational organizations along with the treaties of rights spawned by such bodies. A formula for a better and more peaceful epoch is being sold to the Third World not as Western culture but as the epitome of universal morality and decency. One element of this worship is that Western states must be exemplary in their obeisance to the new peaceful international standards of conduct even when corrupt states are not. The new America entirely lacks patience with this kind of self-restraint. The success of this leftist project depends entirely on convincing outsiders that it is reason incarnate rather than just Christianity for outside consumption. That is why the European Union rejected any reference to Christianity in its draft founding document. It is why European bien-pensants get so exercised about the political influence of the religious Right in America. And it is why Europeans have responded to the Islamic challenge by demonizing not Islamicists, but creatures called “fundamentalists.” For the pretense must be that we are all guilty, all struggling against the same threat of fanaticism.