Books Reviewed

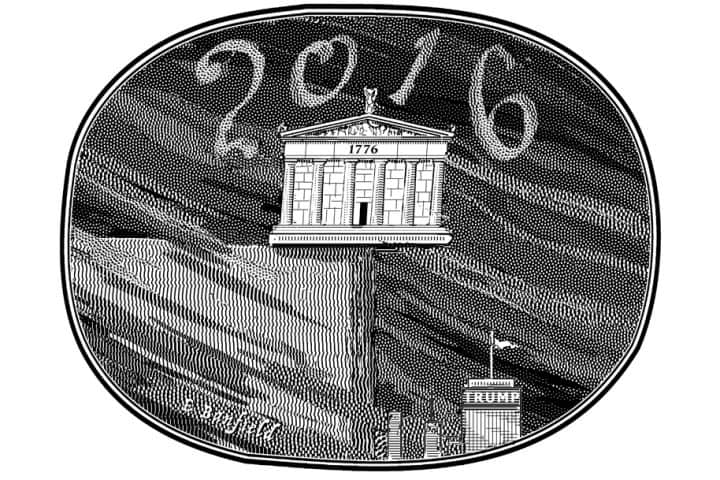

George Thomas’s The Founders and the Idea of a National University is much more than a historical narrative. It is a work of civic art. The title is unassuming: one expects a historical study of the (failed) attempts to establish a national university in the United States—and the expectation is not disappointed—but the author’s concern is decidedly broader and much more ambitious. Thomas’s book is about American identity and the character of the nation and its people, and it offers a troubling prognosis for the political health of the country.

How did the founders envision the nation and constitutional order they established? What did they believe was required to support and preserve it? Is our current generation sufficiently engaged in the civic work required to secure our future freedom and happiness?

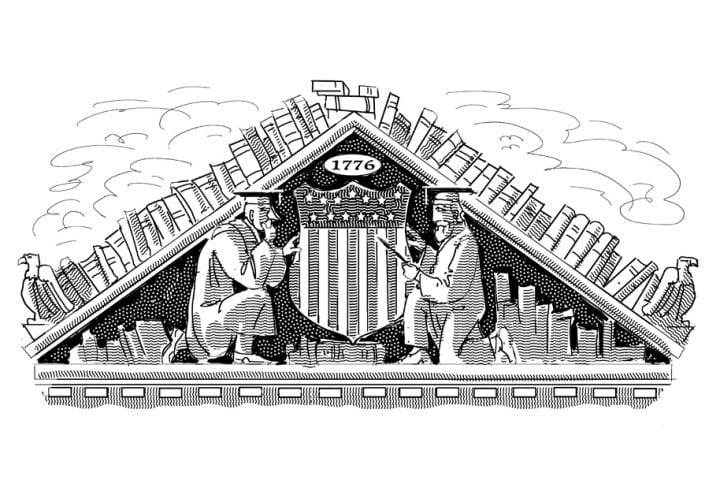

A professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, Thomas begins to answer these questions by recounting the efforts of American presidents and other statesmen to establish a national university. Many iconic figures tried—George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Benjamin Rush, Noah Webster, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Quincy Adams, Ulysses S. Grant, even Rutherford B. Hayes and James A. Garfield—and none succeeded. Thomas is interested in the serious political purpose behind these failed efforts. A “national university project speaks to something…foundational,” he writes. “[I]t speaks, at root, to the understandings presupposed by the Constitution that must be thought and lived” by the American people.

At root, those included such notions of federalism as whether a national university would help cement the Union—could seal national consciousness by means of a sort of West Point for statesmen. In short order, Thomas expands the focus, looking beyond our constitutional arrangements to the cultural, intellectual, and ethical beliefs and habits that are necessary to make American constitutional politics work. Quoting from the University of Virginia political scientist James Ceaser, he argues that political culture can only be

understood ultimately by reference to the ideas that govern how people see the world and formulate their opinions. The task of maintaining a political culture of liberty requires the search for a set of philosophic ideas, capable of being embodied in the mental habits of citizens, that can provide people with the means and the will to maintain their freedom.

The history of the attempts to establish an American national university is a kind of prologue to Thomas’s inquiry into the challenges of creating and maintaining a common civic commitment in America.

* * *

One of these challenges is the complex relationship between religion and politics. Categorizing the United States as the preeminent political order built on “liberal or modern constitutionalism,” Thomas argues that men like Jefferson and Madison sought to “moderate religious beliefs” to reconcile them with secular liberalism. The national university was intended to play a role in this momentous socio-political transformation.

But what sort of religious belief can accord with Jefferson’s and Madison’s liberal constitutionalism? Does the moderation of religious belief mean that it is subordinated to secular liberal principles? Is this the American Founders’ conception of religious liberty? Or is there somehow a place reserved for the sanctity of conscience and priority of faith in modern liberal America? Thomas raises all these questions and invites his reader to answer them.

The famous American solution to the tension between religion and politics is the protection of religious freedom—“the great separation” between the civil sphere and religious authority. But a political order built on religious liberty, Thomas argues, is especially in need of civic education. Religious freedom and the welcoming of immigrants with different customs and traditions result in a diverse citizenry with powerful centrifugal tendencies. A “shared constitutional mind-set” is needed that can counteract these tendencies and unite citizens’ sentiments and views. How can a civic education in the common principles of the nation be accomplished? Thomas cites James Madison, who argued that a national university,

By enlightening the opinions, by expanding the patriotism; and by assimilating the principles, the sentiments and the manners of those who might resort to this Temple of Science, to be redistributed in due time, through every part of the community; sources of jealousy and prejudice would be diminished, the features of national character would be multiplied, and the greater extent given to Social harmony. But above all, a well constituted Seminary, in the center of the nation, is recommended by the consideration, that the additional instruction emanating from it, would contribute not less to strengthen the foundations, than to adorn the structure, of our free and happy system of Government.

According to Madison, the very purpose of a national university was to form a national character and make Americans one people.

The thought that higher education and civic education could go hand in hand in this way has all but vanished in contemporary America. The dominant view in academia today is that liberal education must be grounded in “neutrality” toward substantive principles of justice. Thomas’s book raises the question whether a free people can remain free—or indeed, can be “a people” in any genuine sense—in the absence of a common, substantive conception of justice. Beyond such “neutrality” and mere careerism, Thomas sees, as does anyone with eyes to see, the anti-national—even anti-American—sentiment that is cultivated in our institutions of higher learning. None of the top-ranked colleges and universities in the United States requires a course in American government, thought, or culture, for example, but some do require students to take a course on “Global Citizenship.”

* * *

If the founders were correct that liberty cannot be maintained without a well-informed citizenry, then the contemporary view and practice of liberal education will be catastrophic for the American experiment. Is there an alternative? What if today’s institutions of higher learning were tasked with the responsibility of teaching the principles of liberty and self-government? Or if a national university were formed by bringing together professors from America’s most elite universities to instill these principles in the minds and hearts of future American statesmen and stateswomen? Thomas does not say so, but he seems to imply that this might be akin to what we might call the Educators’ Dilemma: “Who will educate the educators?” Those who do not believe in the principles upon which the nation was founded are precisely the ones to whom we would naturally look to educate future generations in these principles.

George Thomas’s book shows us eloquently that the American experiment is not self-sustaining. Our Constitution and way of life were set in motion by an earlier generation that understood that institutions and laws do not make a people. The future of America depends—as it has always depended—on the hard work of citizenship, and citizenship in a self-governing nation requires education in, and dedication to, the principles that instill vigor and spirit into the life of the nation. That education is what proponents of a national university sought to offer, and in whatever form we may get it, this study powerfully reminds us that we need that education now more than ever.