Books Reviewed

In January 2002, a former student of Appalachian Law School in Virginia, who had flunked out the year before, returned to discuss his academic suspension. Unable to achieve reinstatement, he went into the office of the school’s dean and shot him fatally with a .380 semiautomatic handgun from point-blank range. He then did the same to one of the school’s professors. On his way out he shot four female students, killing one and wounding the others in the abdomen, the throat, and the chest. The carnage ended, according to nearly all the news accounts, when several students tackled the offender as he exited the building. According to John Lott, however, 204 of 208 news stories on the incident somehow failed to mention a telling fact about the offender’s apprehension: two male students ran to their cars to get their guns, and by brandishing one at him forced the killer to drop his weapon. Then they tackled him.

The reporters (and perhaps their editors) failed to mention this dramatic use of guns for self-defense despite the fact that one of the student heroes had explained in detail, to more than 50 reporters, how he and his friend had ended the rampage. When Lott called the Washington Post to find out why its story hadn’t mentioned the guns, the reporter, who had written only of the students “pouncing” on the offender, confirmed that both the armed students had told her the same story but that she didn’t focus on the “details” of the incident; also, “space constraints” were a factor. Even more striking, the Associated Press media relations manager, while denying any intention to downplay the defensive use of guns, expressed his shock at the students’ actions. As he told the Kansas City Star, “I thought, my God, they’re putting into jeopardy even more people by bringing out these guns.”

If the American people don’t realize how often guns are used for self-defense, they are hardly to blame; the media, especially the national media, don’t often tell them. Lott offers another example. Five years before the attack at Appalachian Law School, 16-year-old Luke Woodham made national headlines when, after stabbing his mother to death at home, he took a rifle to his high school in Pearl, Mississippi, and shot nine of his classmates, killing two, including his girlfriend. Scarcely reported at the time was that an assistant principal apprehended Woodham only after running to his pickup to retrieve his .45 caliber pistol (parked far enough from the school to avoid violating the 1,000 foot “gun-free zone” required by federal law). “I had my pistol’s sights on him,” the school official explained later. He ordered Woodham to lie on the ground: “I put my foot on his back area and pointed my pistol at him.”

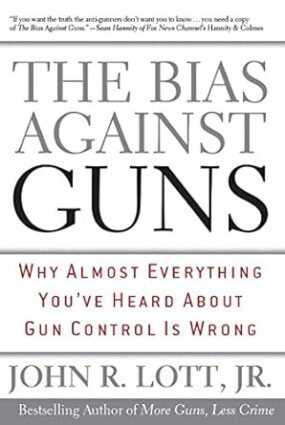

Why such underreporting of the use of firearms for self-defense? Lott suggests two broad reasons. First, according to survey data, about 95 percent of the time that guns are used in self-defense, they are merely brandished by the potential victim. Because no one is actually shot or killed, the incident is not deemed truly “newsworthy.” The more troubling explanation, however, is that too few people in the media are willing to recognize “the positive effects of guns: that they often save innocent lives.” Guns, Lott argues, have both benefits and costs. The task of empirical analysis is to determine “which of these two effects is greater.” Building upon research he first presented in his seminal 1997 article, “Crime, Deterrence, and Right-to-Carry Concealed Handguns” (with David Mustard) and in his controversial 1998 book, More Guns, Less Crime, Lott concludes in The Bias Against Guns that there is “compelling evidence indicating that guns make us safer.”

Readers of Lott’s previous book who may have found daunting the task of working through his detailed and often complex statistical analyses will be pleased to learn that the current volume is much more accessible to a broad audience. Here Lott has done an outstanding job of presenting statistical results in a way non-experts can understand. Yet the technical nature of the underlying methodologies will once again generate in the criminology and economics journals substantial debate over his findings. If the past is any guide, Lott will relish the opportunity to defend those findings. (He sometimes brings his laptop to panels at professional meetings and conducts analyses as needed, on the spot.)

The Bias Against Guns also covers a wider range of gun-control issues than his previous book, which focused mainly on state laws regulating the right to carry concealed weapons. Among the issues analyzed here are the impact of gun control laws on multiple public shootings; the effects of “safe storage” laws on crime rates, gun accidents, and suicides; and the impact on crime rates of waiting periods, gun show regulations, and assault weapons bans. Drawing upon his own analyses and occasionally the work of others, Lott presents an impressive array of findings:

- defensive uses of guns in the United States number about two million per year (dwarfing the number of gun crimes);

- accidental gun deaths of children are quite rare (less frequent, for example, than the death of children in adult beds by being “wedged between the mattress and adjoining wall or the headboard”);

- the prevalence of concealed handguns in Israel (carried by up to ten percent of the adult population) virtually ended terrorism by machine gun, previously preferred to bombings;

- the virtual banning of the private ownership of handguns in the United Kingdom and Australia resulted in an explosion of violent and gun-related crime in those two countries and explains why most burglaries in Britain occur while the dwelling is occupied, compared to just 13 percent of burglaries in the United States, where would-be burglars face a non-trivial chance of being shot;

- right-to-carry concealed handgun laws (now the rule in 33 states) significantly reduced the number and severity of public shootings;

- safe-storage laws (requiring guns to be locked up, fitted with trigger locks, or stored unloaded) have no effect on accidental gun deaths or total suicide rates, but do result in more crime (apparently by making self-defense more difficult);

- none of the other popular gun control measures—such as waiting periods (Brady Law), gun show regulations, and assault weapons bans—reduce crime, and may even increase it.

Although Lott rightly argues against policymaking by anecdote, especially since the anecdotes tend to come to us from a biased media, he wisely scatters his own telling anecdotes throughout his book. Perhaps none is more to the point than the following:

A building contractor, on his way home from work, picked up three young hitchhikers. He fixed them a steak dinner at his house and was preparing to offer them jobs. But two of the men grabbed his kitchen knives and started stabbing him in the back, head, and hands. The attackers only stopped when he told them that he could give them money. But instead of money, the contractor grabbed a pistol and shot one of the attackers. The contractor said, “If I’d had a trigger lock, I’d be dead. If my pistol had been in a gun safe, I’d be dead. If the bullets were stored separate, I’d be dead. They were going to kill me.”

Ignore the potential use of handguns in self-defense and it becomes easy to argue for trigger locks, gun safes, and storing bullets separately. Surely our children will be safer, proponents argue. To this Lott responds, however, that there is no empirical evidence that such restrictions have any positive effect on accidental gun deaths, and such restrictions may well render a weapon at home useless when most needed.

Now include the whole range of gun control measures designed to make us all safer: waiting periods, safety testing, bans on inexpensive handguns (so called “Saturday night specials”), requirements that private sales at gun shows employ background checks, etc. The cumulative effect of these measures is necessarily to increase the expense and the hassle of owning guns, especially handguns. Make an activity more costly and you are likely to get less of it. Thus, Lott’s fear: fewer responsible, law-abiding citizens will own and carry weapons. And if more guns result in less crime, then fewer guns will likely lead to more crime, as our British cousins appear to be learning.

Lott himself is persuaded that the disarming of America is the conscious intention of the leading handgun control groups and politicians, despite their protestations to the contrary. He quotes, for example, Pete Shields, the founder of Handgun Control, Inc. (now the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, run by Sarah and Jim Brady): “The first problem is to slow down the number of handguns being produced and sold in this country. The second problem is to get handguns registered. The final problem is to make possession of all handguns and all handgun ammunition—except for the military, police, licensed security guards, licensed sporting clubs, and licensed gun collectors—totally illegal.” Lott also tells of serving on a panel to debate the merits of cities’ suing gun makers and hearing Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell (now governor of Pennsylvania) deny that he wanted to take guns away from law-abiding citizens. Later, however, Rendell, not realizing that Lott was standing behind him, put his arm around an anti-gun activist and said, “I just can’t say publicly what we want to do, we have to take these things slowly.”

In documenting the many manifestations of the anti-gun “hysteria” in the United States, Lott tells the story of how he and his wife took their four sons to the Yale University Health Service for medical checkups in 1999. “Prominently displayed posters on the walls warned against keeping handguns in the home.” After the nurse practitioner took the children’s medical histories, “she asked us whether we owned guns and whether they were locked up or loaded.” As Lott responded with data to show that guns saved lives and “were much less of a risk than other common household items,” his wife, worried that he “was antagonizing our children’s health care providers, forcefully ground her heel into my foot to signal me to stop pursuing the issue.” For the past six years John Lott has been grinding his heel into the anti-gun establishment with sophisticated, comprehensive, and trenchant empirical analyses. Indeed, it is hard to think of a social scientist in recent years whose work has been so frequently cited in public policy debates.

Yet if pro-gun politicians are inclined to embrace Lott’s central thesis—more guns, less crime—and anti-gun politicians recoil in horror, the debate in the scholarly community continues at professional conferences and in the pages of leading academic journals, especially surrounding the significant technical issues involved in Lott’s statistical analyses. No one, however, defends his work more energetically than John Lott, whose two books on guns contain extensive responses to his critics. Even now a panel of the National Academy of Sciences is assessing current research on firearms violence. In The Bias Against Guns, Lott attacks the panel as “stacked” with anti-gun academics and researchers. Yet no less a figure than James Q. Wilson, a member of the panel, has publicly expressed his confidence that the panel will produce a balanced and apolitical report, which is expected within the next 12 months.

Unfortunately, The Bias Against Guns has not yet received the attention it deserves, with almost no reviews in the nation’s leading newspapers and journals of opinion. By rights, Lott’s new book ought to have a powerful effect on the gun control debate in the country. One fears, though, that the bias is so strong that it is impervious to facts. As Lott convincingly shows, the stakes in this debate are unusually high.