Books Reviewed

he New Yorker food critic Calvin Trillin once called Memphis “a serious barbecue town long before barbecue sauce began being displayed in Eastern gourmet stores next to extra-virgin olive oil and balsamic vinegar.” But mostly the city impressed him as “a place where an extra ion of American ingenuity might be hanging in the air.” He offered as proof four 20th-century institutions that each became indispensable, meeting a demand that didn’t exist until something was created to satisfy it: the supermarket (Piggly–Wiggly), the express delivery system (Federal Express), the modern motel (Holiday Inn), and Elvis Presley.

he New Yorker food critic Calvin Trillin once called Memphis “a serious barbecue town long before barbecue sauce began being displayed in Eastern gourmet stores next to extra-virgin olive oil and balsamic vinegar.” But mostly the city impressed him as “a place where an extra ion of American ingenuity might be hanging in the air.” He offered as proof four 20th-century institutions that each became indispensable, meeting a demand that didn’t exist until something was created to satisfy it: the supermarket (Piggly–Wiggly), the express delivery system (Federal Express), the modern motel (Holiday Inn), and Elvis Presley.

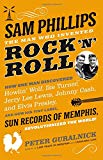

Clarence Saunders, whose Piggly-Wiggly replaced the aproned storekeeper behind the counter, and Fred Smith, who invented long-distance overnight delivery, are not mentioned in Peter Guralnick’s new, extravagantly subtitled Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll—How One Man Discovered Howlin’ Wolf, Ike Turner, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley and How His Tiny Label, Sun Records of Memphis, Revolutionized the World!. But Elvis and the others are characters in the book, along with B.B. King, Roy Orbison, and Rufus Thomas. So is Kemmons Wilson, the young entrepreneur who hated taking driving vacations with a carload of five boys and finding that the “tourist cabins” lining the nation’s highways in the early 1950s were dirty, made you pump in quarters if you wanted to watch television, and charged an extra $2 per day for each kid. In 1952 he opened, in Memphis, the first Holiday Inn. The common denominators shared by all these characters are Memphis and Sam Phillips.

Memphis sits on four bluffs above the Mississippi River at the northern crown of the Mississippi Delta. Located squarely at the juxtaposition of three states—Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi—it is, for most practical purposes, the largest city in each of them. Throughout its history, the city has been a magnet for Arkansans, Mississippians, and west Tennesseans from the countryside.

Phillips, raised in a small town in nearby northern Alabama, grew up dreaming of the big city. When he was 16 he arranged a car trip with his brother and some friends, purportedly to hear an evangelist in Dallas, but really to stop en route in Memphis and gawk at Beale Street. “We arrived at four or five o’clock in the morning in pouring down rain, but I’m telling you, Broadway never looked that busy,” Phillips told Guralnick. “It was like a beehive, a microcosm of humanity—you had a lot of sober people there, you had a lot of people having a good time. You had old black men from the Delta and young cats dressed to kill. . . . And I knew I was going to live in Memphis some day.”

Phillips worked his way from Alabama to Memphis through a series of jobs at small radio stations, but his real ambition was to open a recording studio where he could capture the music of “all these people of little education and even less social standing, who had so much to say but were prohibited from saying it.” In 1949 he found a $75 per month, hole-in-the-wall storefront at 706 Union Avenue with room for an 18 by 30 foot studio, and began putting out records on the new Sun label.

After scrambling to pay the bills by recording weddings and church services—the sign in the window read: “WE RECORD ANYTHING—ANYWHERE—ANYTIME”—Phillips opened his studio’s door one day to find young Riley King of Indianola, Mississippi, known variously as the Singing Black Boy, the Singing Blues Boy, and then, permanently, as B.B. King. In his wake came another blues singer from rural Mississippi, Chester Arthur Bennett, better known as Howlin’ Wolf—the howl influenced by the “blue yodel” of Jimmie Rodgers, the Father of Country Music.

That was the point: to record black blues that was influenced by white country music and—eventually and more profitably—to record white country music inflected with black rhythm and blues. “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel,” Phillips said, “I could make a billion dollars!” As if on cue, on June 26, 1954, a 19-year-old “good-looking boy with acne on his neck, long sideburns, and long, greasy hair combed in a ducktail that he had to keep patting down” came into the studio: Elvis Presley. After a few frustrating sessions of pop songs, spirituals, and “just a few words of [anything] I remember . . . ,” Elvis later said, “I started kidding around” with “That’s All Right, Mama,” an old blues number by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. “The rest of the session went as if suddenly they had all been caught up in a fever dream,” Guralnick writes. Phillips was ecstatic: he had his white boy and black sound.

With an equally jumped-up version of Bill Monroe’s bluegrass classic “Blue Moon of Kentucky” on the B-side, Elvis cracked the “POP—HILLBILLY—R & B” charts. “We knocked the shit out of the color line,” Phillips said. Soon, every young white singer in the Midsouth who, like Phillips and Elvis, wanted to infuse his music with the rhythm and raw feel of Saturday night at a roadside juke joint and the earnest abandon of Sunday morning in a black country church began banging on Sun’s door.

Among them were J.R. Cash (his given name) from Dyess, Arkansas, whose first hit with Sun was “Cry! Cry! Cry!”; Carl Perkins from Jackson, Tennessee (“Blue Suede Shoes”); and Jerry Lee Lewis from Ferriday, Louisiana. (“Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On”). Guralnick observes that Phillips demanded “a thoroughly professional recording that sounded as if it had been put together with a minimum of polish and a maximum of spontaneity.”

The casualties were Phillips’s roster of black musicians, whose records had seldom made him much money. He “discarded all of his black talent . . . when Elvis came along,” said Rufus Thomas—only a slight exaggeration. In this, Phillips missed a boat the size of an ocean liner. During the early 1960s, Memphis-based Stax Records created a massive crossover market for gritty, gutbucket rhythm and blues by the likes of Thomas, his daughter Carla, Sam and Dave, Isaac Hayes, Otis Redding, and Booker T and the M.G.s.

Nevertheless, Sun reached a musical apex on December 4, 1956. Lewis was playing piano at a Carl Perkins recording session when in walked Elvis, already a national sensation. With Cash also in the studio, Phillips had his “Million Dollar Quartet.” The four fooled around with various R & B and country numbers, including a version of “Don’t Be Cruel” copied from a black singer who Elvis heard in a Las Vegas nightclub and preferred to his own, million record hit. “But at the heart of the session, inevitably,” Guralnick writes, “are the spirituals on which they all grew up”—“Softly and Tenderly,” “Just a Little Talk with Jesus,” “I Can’t Make It by Myself,” “I Shall Not Be Moved,” “There’ll Be Peace in the Valley,” and others. Happily, Phillips let the tape keep running, and a recording of the session, available on CD from Snapper UK, inspired the 2010 hit Broadway musical Million Dollar Quartet, as well as a cable television series that is being filmed in Memphis and will air on CMT.

That December 1956 session was a swan song of sorts. The Elvis who stopped by Sun studio was no longer a Sun artist: he’d signed for bigger bucks with RCA in 1955. Over time, the other quartet members joined the migration from Sun to the major labels: Cash—rechristened as Johnny by Phillips—and Perkins to Columbia, Lewis to Mercury. Phillips’s last big discovery, Charlie Rich, joined Elvis at RCA.

It’s called the music business for a reason, and Phillips’s struggle to make records he loved while keeping his shoestring operation financially solvent was ceaseless. Phillips’s friend Kemmons Wilson, having hit a gusher with Holiday Inn, kept him afloat at various times by vouching for his creditworthiness with a local record presser, investing in his all-woman Memphis radio station (aptly, WHER), and hiring him to produce records for sale at his motels, the last of these a venture that went nowhere.

Phillips’s heyday passed, but not without leaving a long trail. “In 1997 Life magazine listed the discovery of Elvis Presley (and the birth of rock and roll) at number 99 in a special issue dedicated to ‘100 Incredible Discoveries, Cataclysmic Events, [and] Magnificent Moments of the Past 1,000 Years,’” Guralnick notes, “just ahead of ‘Fixing the Calendar, 1582.’” Time included it among “Great Events of the 20th Century.” Phillips was one of the 12 inaugural inductees to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986, along with Elvis and Jerry Lee, and was added to the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2001. He died in 2003 at age 80.

“Sam’s a guy pretty much like me,” Kemmons Wilson said. “He knew what he wanted, and he wanted to do it his way.” What Phillips wanted was to unlock the “wealth of talent out there just waiting to be discovered and”—as with Piggly-Wiggly, Holiday Inn, and FedEx—“a world just waiting to embrace it, even if that world had no idea what it was waiting for.”

Why was Memphis such a center of innovation during the middle decades of the twentieth century? Part of the explanation is particular to that city, which as a regional magnet for blacks migrating north and whites moving from farm to city enjoyed a healthy confluence of ambitious young people on the make. But part has to do with the general openness to new people and new ideas that comes from being off the Boston-to-New York-to-Washington axis of calcified institutions and old money. In a sense, Sam Phillips’s true descendants are people like Jeff Bezos of Seattle, Steve Jobs of Palo Alto, and Michael Dell of Austin.