Books Reviewed

More than a decade after the 2008 financial crisis, proclamations of the death of neoliberalism have become cliché, despite—or perhaps because of—the fact that neoliberalism remains the dominant mode of political economy in the West. Neoliberalism, to offer a simple definition, seeks to maximize the free movement of capital, goods, and labor, and prefers the insulation of economic institutions from political influence or direction. Although there has been a modest reversal of globalization and a revived focus on securing supply chains in recent years, the neoliberal paradigms of the 1990s and 2000s still shape our world. Neoliberalism is not dead, merely disliked. And even if few on the Left or Right embrace the neoliberal label or its policy legacy today, there is no agreed-upon replacement.

Two new books seek to make sense of this confusing situation. The first, J. Bradford DeLong’s Slouching Towards Utopia, is a progressive neoliberal’s attempt to grapple with the economic policy failures of recent decades without abandoning the underlying neoliberal framework. The second, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order by Gary Gerstle, a left-wing critic of neoliberalism, emphasizes the historical contingencies that drove both the rise and fall of the New Deal political economy and the trajectory of its neoliberal successor. Gerstle’s book, in particular, contains many valuable insights, yet both stumble when explaining the present political-economic impasse, and neither offers a way out of it.

***

A better title for Delong’s book would be Slouching Towards an Argument. His 600-page tome covers everything from Clinton White House gossip to the battlefield tactics of the Wehrmacht. These disparate parts do not always add up to a whole but, with some interpretive effort, a few recurring leitmotifs can be identified.

DeLong underscores the continuities of economic history. “History does not repeat itself,” he writes, “but it does rhyme.” As if to both reinforce and contradict this claim, DeLong repeats the phrase verbatim, and ad nauseam, throughout the book. The “long twentieth century,” which he identifies as 1870 to 2010, however, stands out as uniquely successful in escaping Malthusian scarcity, thanks to the combination of globalization, innovation, and social democracy (generous welfare programs along with inclusive democratic representation). His book’s narrative drama is provided by the philosophical conflict between economists Friedrich Hayek and Karl Polanyi, whom DeLong uses as avatars of the eternal antagonism between market dynamism and communal solidarity. The moral of the story is that “professional economists” like DeLong are needed to moderate this undergraduate-level debate and find the proper balance required for peace and prosperity. The post-World War II “shotgun marriage of Friedrich von Hayek and Karl Polanyi, blessed by John Maynard Keynes,” was “as good as we have so far gotten,” he writes.

DeLong’s own intellectual journey figures into his chapters covering recent decades. In his early career, which included a stint as deputy assistant secretary of the treasury in the Clinton Administration, DeLong acquired a reputation as a leading neoliberal Democrat. More recently, he has repudiated some of these commitments. Slouching Towards Utopia contains DeLong’s accounting of the policy errors underwritten by neoliberal thought, and his regret that more progressive alternatives were not pursued. But it is precisely in his criticism of neoliberalism that DeLong reveals his fundamental attachment to its basic conceptual framework—and shows why it has been so difficult for the centrist establishment to break from failed policy models.

***

For Delong, moving away from neoliberalism means adopting a bit more welfare and regulation—a little more “Polanyi” and a little less “Hayek.” But these abstractions obscure essential questions: Is the Hayekian market the sole source of innovation and growth? Is the Polanyian political community merely something one must make occasional concessions to in order to avoid extremist backlash? Do the market and state function as opposites in a simplistic binary? DeLong seems to think the only important debate is over the size and scope of welfare and regulatory programs. Yet what if the state’s role is not confined to wealth redistribution; what if it is also critical to technological advance and economic growth?

These questions point toward the glaring contradiction at the heart of DeLong’s worldview. He sees globalization, innovation, and social democracy as the keys to success in the long 20th century and beyond. But he never really reflects on the inherent conflicts between them.

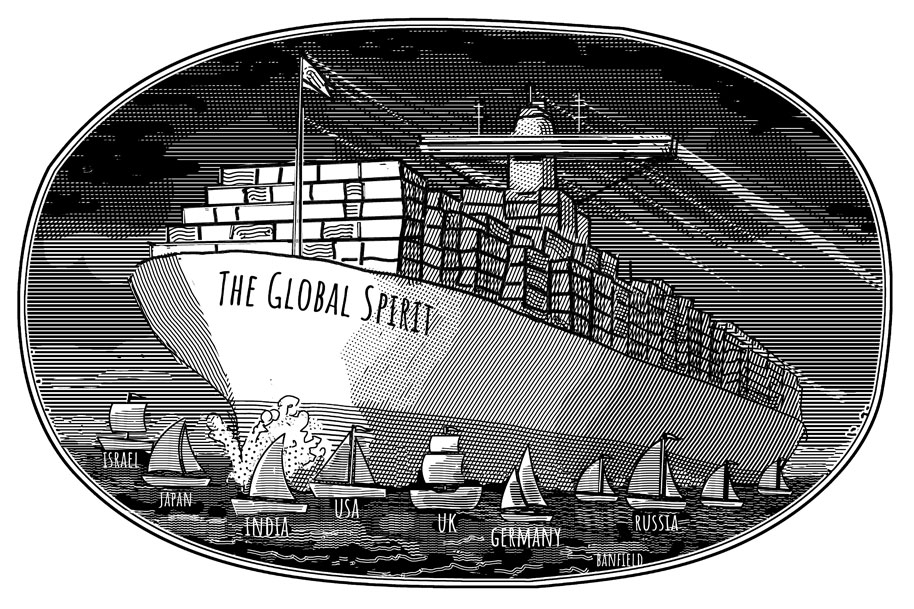

The tensions between globalization and social democracy have received more attention in recent years (see, inter alia, the work of Michael Lind, Wolfgang Streeck, Michael Pettis, and Thomas Fazi) as they have become increasingly obvious. The further globalization proceeds, the greater the ability of multinational corporations and finance to undercut labor through offshoring, trade, and immigration, as well as to avoid taxation and to undermine social contracts generally. DeLong, however, does not seriously engage with these issues. He sees contemporary globalization as a fait accompli brought about by container shipping and internet communications, and he blames the decline of Western welfare states on bad-faith Republicans and well-meaning Democrats. But regarding how to build or sustain a robust social democracy amid the race-to-the-bottom pressures of globalization, DeLong has nothing to say.

***

A less discussed, though perhaps more significant, tension exists between globalization and innovation. Peter Thiel offered the most succinct articulation of this conflict in his book Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future (2014), in which he posited globalization (going from 1 to n) and innovation (going from 0 to 1) as opposites. Sociologist Liah Greenfeld provided a more academic treatment in The Spirit of Capitalism: Nationalism and Economic Growth (2001), which explored the interconnections between capitalist development and nationalist rivalry from the early modern period through the 20th century. A more recent scholarly literature (see, for example, the work of Mariana Mazzucato and Robyn Klingler-Vidra) has shown how national innovation efforts—often motivated by geopolitical exigencies—have been central to technological breakthroughs and the formation of high-tech industries, as in the cases of Israel, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, and China, not to mention America’s Manhattan Project, Apollo space program, and early Silicon Valley.

DeLong, by contrast, struggles to explain why the magic of globalization has consistently failed to lift all boats, particularly countries in the Global South. He blames overly strong states, corruption, and lack of democracy. Yet China’s remarkable rise (to take only the most prominent counterexample) has occurred under an authoritarian state with no shortage of corruption. A less ideological analysis would acknowledge the importance of state-led national development strategies and the centrality of industrialization. Countries with the state capacity and political will to pursue such strategies (such as the “Four Asian Tigers”) have succeeded in joining the developed world. Those which cannot, which rely on liberal economists to find the perfect balance between Hayek and Polanyi—employing the state only to redistribute wealth—have fared much worse.

DeLong is too polite to mention, or perhaps too ideologically blinkered to observe, that globalization is at bottom a euphemism for imperial expansion—though he comes close when he awkwardly pairs globalization with American exceptionalism at one point in the book. This was as true for ancient Rome and Siglo de Oro Spain as it was for Victorian Britain and the “end of history” United States. It is probably unfair to say that (neo)liberal economic thought itself is merely a justification of empire, but the fact that its popularity tends to follow imperial fortunes is not especially surprising. Despite liberalism’s rhetorical emphasis on dynamism, the belief that markets bring about perfect outcomes offers a convenient rationalization of the status quo. Yet as the economist Albert O. Hirschman recognized, faith in the invisible hand tends to be more debilitating for the hegemon than its challengers, as it prevents a response to the economic nationalist strategies of rising competitors which consciously exploit global market arrangements. Consequently, while the financial sector of the imperial center inflates, its underlying industrial and technological advantages erode. Such was the case for Great Britain vis-à-vis Germany and the United States in the early 20th century, and for the United States vis-à-vis China in the early 21st.

When “the scientific pretensions of these ideologies have been exploded,” James Burnham wrote in The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World (1941), they are revealed as “at best just temporary expressions of the interests and ideals of a particular class of men at a particular historical time.” So it is with Slouching Towards Utopia. DeLong’s book is not a serious work of political economy or a coherent history of the long 20th century. It is rather a long and rambling apologia for the “end of history,” on the one hand, and “professional economists,” on the other. It shows that even if the long 20th century has ended, the ideological chimeras of the long 1990s still survive, zombie-like, in the minds of neoliberal economists. The book’s combination of globalization, innovation, and social democracy is utopian because it can never be sustained, as its internal contradictions prove self-undermining. Today, those contradictions should be obvious. But whether or not history rhymes, DeLong seems doomed to continue repeating his mistakes.

***

While Delong traces the contours of the long 20th century, Gary Gerstle focuses on the short version extending from 1917 to 1991, the duration of the Soviet Union. Indeed, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order is primarily about the impacts of the rise and fall of the Soviet Union on U.S. domestic politics.

For Gerstle, the existence of a genuine alternative to Communism was essential to both the creation of the New Deal order and its unraveling. It was precisely the threat posed by Communism, in Gerstle’s account, that motivated capitalist nations to construct social democratic institutions and lay the foundations of postwar mass prosperity. In addition to industrial and technological rivalry, the Cold War featured an intense competition between capitalist and Communist societies over which could deliver a better standard of living for the common man, as exemplified by the 1959 “Kitchen Debate” between Vice President Richard Nixon and the USSR’s Nikita Khrushchev. Without such external pressure, Gerstle argues, the United States might never have left the Gilded Age political economy that characterized the pre-New Deal era and arose again soon after the Cold War.

At the same time, the effort to contain the Soviet Union abroad slowly weakened the foundations of U.S. economic power. In order to support its allies, America granted them privileged access to the U.S. consumer market while allowing countries like Germany and Japan to maintain high tariffs. Initially, when the U.S. industrial colossus towered over war-ravaged economies, these asymmetries had little domestic impact. But over time the resulting foreign industrial competition—combined with spending on both Vietnam and the Great Society, as well as the peaking of U.S. oil production—precipitated a balance of payments crisis and made the New Deal era’s high taxes and strong unions harder for the U.S. corporate sector to bear. Already in 1971, Gerstle recounts, “a blue-ribbon panel appointed by Nixon reported that ‘the nation’s economic superiority was gone.’” The breakdown in the 1970s of the Bretton-Woods currency regime established in 1944 would have massive implications, while Wall Street grew increasingly unhappy with a falling stock market, small business chafed at expanding regulatory intrusions, and consumers wearied of inflation and gas lines.

***

Gerstle’s analysis of the material factors behind the New Deal order’s decline is compelling, if not especially original. The book’s greatest insights, however, lie in its treatment of the multifaceted ideological motives behind the rise of neoliberalism. Countless leftist polemics, along with many hagiographies of Reagan, have presented neoliberalism as a decidedly right-wing affair, yet it always included left-wing currents. Gerstle is not the first author to explore Left neoliberalism, but his examination of it is perhaps the most penetrating and systematic, and his discussion of the convergence between Left and Right neoliberal frameworks is perhaps the most illuminating.

Gerstle identifies two neoliberal outlooks—one he terms the “neo-Victorian,” and the other the “cosmopolitan”—which complement and conflict with each other at different points. Neo-Victorianism is the moral code of Right neoliberalism, emphasizing virtues like self-reliance, hard work, and “law and order,” as well as certain traditional expressions of civic and familial obligation. Gerstle mainly sees neo-Victorianism as a value system promoted by Right neoliberals in order to sustain the market—to ensure individuals remain fit for participation in it. But significantly, many conservative neoliberals argued that the market would also help sustain traditional values—William F. Buckley, Jr.’s fusionism in a nutshell. Cosmopolitanism, by contrast, is the left-wing variant of neoliberal morality. It emphasizes multiculturalism, self-expression, and choice—John Stuart Mill’s “experiments in living”—less market discipline and efficiency and more the fluidity of market society. Gerstle identifies figures like Michel Foucault and the 1960s New Left as its leading intellectual influences.

***

Gerstle deftly traces these dynamics across presidential administrations and intellectual movements. At times, Left and Right neoliberals participated in intentional collaborations, such as A New History of Leviathan: Essays on the Rise of the American Corporate State (1972), a volume coedited by Murray Rothbard and Ronald Radosh that featured prominent New Left and libertarian contributors. In other cases, the convergence was more coincidental: Robert Bork and Ralph Nader were both consumer welfare enthusiasts; diehard Reaganites and ex-hippies celebrated the Silicon Valley “new economy” and its ethos; Chicago school economists and radical feminists attacked traditional views of the family; Left and Right radicals despised bureaucracy. Another important example not mentioned is the marketization of electric utilities, a favored cause of both countercultural greens and libertarian economists (along with Enron). Amid this backdrop, the Carter, Reagan, Clinton, and both Bush administrations advanced overlapping neoliberal policies on trade, financial deregulation, immigration, antitrust, and beyond, even while cultural polarization between cosmopolitans and neo-Victorians intensified.

Gerstle identifies the George W. Bush Administration as the high point of neoliberalism. The disastrous economic and foreign policy choices of that period require no elaboration here, but Gerstle captures another important element of neoliberal politics: the total opposition to even the most basic forms of strategic planning. This tendency was evident in the administration’s economic policy—including the view that financial market participants would “self-regulate”—but it also manifested, catastrophically, in foreign policy. As Gerstle explains,

Bush ordered no one to develop a serious plan for reconstructing the Iraqi economy and society…. There was no need, in Bush’s eyes, for the U.S. government to undertake such a reconstruction. The market, once suitably activated, would do that work.

On this point, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order could have benefited from the insights of another recently published history, Fritz Bartel’s The Triumph of Broken Promises (2022). Bartel argues that neoliberalism provided a critical technocratic and “scientific” rationale for austerity in the 1970s and ’80s (one unavailable to the Eastern Bloc). The longer-term problem, however, is that the rationalizations for breaking imprudent campaign promises could also be used to excuse bad government and general incompetence. As economist Aaron Renn observed, if government is always the problem, never the solution, then why should politicians be held accountable for governance failures? Why should they even bother with basic elements of statesmanship, like sound planning and execution? Politics becomes a game of focus-grouped slogans and moralism; the heavy lifting is left to the invisible hand.

***

As brilliant as Gerstle’s account of the rise of neoliberalism is, his explanation of its fall is underwhelming. This is partly because neoliberalism hasn’t quite fallen, but Gerstle also gets bogged down in the personal psychologies of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, losing sight of larger political and economic forces.

The basic analytical framework Gerstle uses to explain the rise of neoliberalism, however, yields insights into today’s peculiar stasis. If reports of the death of neoliberalism are greatly exaggerated, it is often because they refer only to the decline of the right-wing variant. This shift is real enough, but it doesn’t encompass all of neoliberalism, as Gerstle outlines.

Although neo-Victorian neoliberalism could be harsh, its justifications were straightforward: it promised superior economic performance and strong traditional values. Since around 2000, though, the U.S. economy has been mired in “secular stagnation”—if not “Brazilianization”—punctuated by speculative booms and busts, with most gains accruing to an ever-narrower set of large capital holders. Meanwhile, in an era of “woke capital,” ubiquitous pornography, pervasive drug use, and broken families, hardly anyone still believes that markets reliably uphold traditional values.

Contrary to innumerable leftist critiques, many on the Right do sincerely believe in traditional and patriotic virtues, and not just for the instrumental purpose of sustaining markets. In recent years, these social conservatives have led the Republican Party’s turn toward “populism” and occasional breaks from neoliberal orthodoxy. Nevertheless, social conservatives (in any politically meaningful sense of the term) are a distinct and embattled minority—among the populace and especially among the elite—in part because of neoliberalism’s corrosive effects. Thus, despite a growing disaffection with the market, they remain wary of a more effective state, which they fear would be used against them. The Left has given them little reason to think otherwise. Pessimistic about their ability to influence power—unable to wrest control of the Republican Party, yet unable to leave it—they default to what might be called a “neoliberalism of fear.” In the Reagan era, conservative neoliberalism had a positive justification; now, obstructionist efforts are often undertaken for their own sake.

***

Cosmopolitan or left neoliberalism was perhaps always destined to win out over neo-Victorianism, if only because its criteria are much easier to satisfy. One can be a multiculturalist and an entrepreneur of the self even in a stagnant economy, and the particulars of this morality are always in flux. Over time, the Democratic Party has moved away from the triangulating policies of the Clinton Administration, but the Left as a whole has only progressed deeper into cosmopolitan moralism. The radical Left’s egalitarian yearnings are not necessarily insincere, but its unyielding commitment to subjectivity and victimhood precludes any real social solidarity or state-building. Like the Right, the far Left now tends to define its goals in negative or oppositional terms: defund the police, abolish ICE, antifascism, antiracism. Today’s self-proclaimed socialists represent a sort of anarchic and moralistic “Left Communism,” which no less an authority than Vladimir Lenin called “an infantile disorder.”

Having rejected the masses as hopelessly racist and reactionary, and abandoned national states for globalism, the locus of Left activism has shifted toward multinational corporations, elite universities, independent “expert” bureaucracies, and major philanthropic foundations. Whatever its professed antipathy toward neoliberalism, the radical Left has come to depend primarily—if not entirely—upon these most neoliberal of institutions.

Hence, on both Right and Left today, the more radical the critics of neoliberal theory, the more they rely upon neoliberal institutions in practice. Neither can easily abandon neoliberalism’s antidemocratic funding and organizational models nor its limits on state action. Centrists, likewise, fearful of both extremes, default to a failing status quo, though they have recently taken some important steps with legislation like the CHIPS and Inflation Reduction Acts.

***

On the other hand, both Gary Gerstle and Brad DeLong, for different reasons, downplay the “statist” elements of neoliberalism. Neoliberals, in contrast to pure libertarians, consciously recognize a role for the state in creating and sustaining markets. Left-wing critiques tend to emphasize disciplinary functions like the “carceral state,” but another issue complicates the basic operation of the market mechanism itself: the contradiction between (neo)classical theory’s assumptions about the incentives of capitalism and the political interests of individual capitalists.

In theory, capitalism tends toward perfect competition; in practice, the capitalist desires monopoly. Theory prescribes laissez-faire; the capitalist desires government favors and public sector contracts. Thus, as the corporate sector becomes more powerful under neoliberalism, firms become more effective at lobbying for subsidies, bailouts, and government spending that can be subcontracted to the private sector, not to mention accommodative monetary policy experiments. In other words, capitalists themselves become the most powerful and motivated proponents of (self-serving) government intervention. Resisting this interventionist impulse would require some countervailing power intent on maintaining the conditions of perfect competition, along with a citizenry willing to endure economic pain in some cases (e.g., avoiding bailouts). Yet neoliberal policy undercuts any institutions that could resist corporate power, and neoliberal doctrine undermines the public spiritedness required to do so.

As a result, instead of textbook capitalism, neoliberal political economy tends toward a sort of corrupted corporatism—one with complex ties between the state and private sectors, as well as high industry concentration, yet no meaningful representation of the public interest. This corporate landscape is littered with companies that take advantage of lax antitrust and financial market incentives to become “too big to fail,” only to also become thoroughly financialized, stagnant, and sclerotic—deeply intertwined with the state if not largely dependent on government subsidies and contracts.

At the same time, the disappearance of the great public projects of previous eras is not accompanied by the shrinking of the state, but by what the pseudonymous Wallace S. Moyle calls the “libertarianoid style” of government intervention: inefficient and opaque efforts to direct government funds to private actors to carry out public programs, such as subsidizing the purchase of private health insurance. This, says Moyle, “allows Democrats to expand the reach of government without having to increase state capacity. It allows Republicans to proclaim at once their compassion for a program’s beneficiaries and their commitment to the free market. And it allows both parties to shower interest groups—from landlords to health insurers—with subsidies.”

***

Both Gerstle and Delong also underappreciate the significance of the rise of the virtual economy. Gerstle documents both Right and Left neoliberal cheerleading of internet technology, and the Democratic Party’s conscious efforts to win over Silicon Valley in the run-up to the 1996 Telecommunications Act. But neither author fully grasps the sea change effected by Silicon Valley’s ascendance.

As far back as the Nixon Administration, as indicated, policymakers began to recognize the waning of U.S. economic dominance. Early neoliberal reforms—as well as ongoing protectionist efforts like Reagan’s Plaza Accord and import restrictions—were aimed at solving these problems. Throughout the 1992 presidential campaign, including in the third-party challenge of Ross Perot, debates over America’s declining industrial base often took center stage. Indeed, up through the early Clinton Administration, these issues had powerful champions. It was only after the information technology revolution of the 1990s, and its visions of a “new economy,” that the political mainstream stopped worrying about the loss of key “old economy” industries. When the tech bubble collapsed in 2000, policy focused not on strengthening domestic industrial competitiveness but on inflating a real estate bubble and debt-fueled consumption. Business investment decisions, likewise, continued to be guided by the search for software-like returns and a focus on asset valuations over income growth.

Yet this political and economic consensus misunderstood key aspects of the internet revolution. Silicon Valley’s breakthroughs were not attributable solely to the magic of markets but also to the commercialization of the last wave of Cold War defense technology initiatives and the great discoveries of New Deal-era corporate labs (which would soon become a target of cost-cutting shareholder activists). Once Silicon Valley became primarily oriented around financial markets and private venture capital, it ceased delivering major productivity-enhancing technologies. Instead, it offered advertising-driven social media platforms and profitless “sharing economy” companies, or more recently levered crypto bets—often just naked attempts to secure monopolies through superior financial resources rather than technology, or to dress up, for example, commercial real estate rental firms as “tech companies.” Crucially, during this transition Silicon Valley largely stopped producing silicon hardware, as the “designed in California, made in China” model became more financially attractive. Today’s Silicon Valley is not simply a story of innovation but represents perhaps the most potent application of a longer-running neoliberal financial strategy aimed at separating intellectual property rents from the capital and labor costs of physical production.

Fundamentally, neoliberalism is an ideology of this virtual economy—both its unmoored financial speculation and the infinite proliferation of (online) identities. In this respect, it is not surprising that the disruptions caused by both COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine conflict—which have demonstrated the political importance and economic value of physical production—have accelerated an even greater shift away from neoliberal policy paradigms than the financial crisis did. The real economy requires the competent coordination of physical supply chains—and capital and labor more generally—in a way that the virtual economy does not. The most important question that will decide the future of our political economy is not how many intellectuals proclaim the death of neoliberalism, or other partisan and theoretical quarrels, but how profound and long-lasting this “reassertion of the real” proves to be.