Ask Americans to name a charity and most will mention their church, a local food bank, the community theater, or, at Christmastime, the Salvation Army. Indeed, these organizations, devoted to providing spiritual and material sustenance, account for the vast majority of charitable groups operating in the U.S. Tax policies encouraging their work have reflected a consensus in favor of civic engagement and strengthening the bonds of civil society through voluntary private efforts rather than government programs.

Over the past 40 years, however, another segment of the nonprofit sector has emerged: organizations devoted to reshaping public policies and our political life. Behind such innocuous names as Arabella or Tides, networks engage in partisan politics, overt lobbying, and support for disruptive movements on college campuses and elsewhere. Tax-deductible contributions are almost always their key source of financial support.

One of these entities, the People’s Forum, received millions of dollars in anonymous money from Goldman Sachs Charities. The funds were used to advise and support disruptive, anti-Israel demonstrators at Columbia University, New York University, and elsewhere. In 2020, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative financially assisted election officials in locations essential for Democratic victories. Rockefeller Brothers Fund and other endowed institutions undertook a successful lobbying effort to convince President Biden to cap the development and export of natural gas. George Soros, the most famous source of financial support for leftist causes, was involved in all three events, but the phenomenon is larger than one man or one philanthropy.

It is not just activists on the left who have stretched our notion of being “charitable.” By most counts, however, conservatives give less money for election-adjacent initiatives. Progressives have weaponized a small but powerful part of the nonprofit world, with impacts that include diminished tax revenues and dubious public policies.

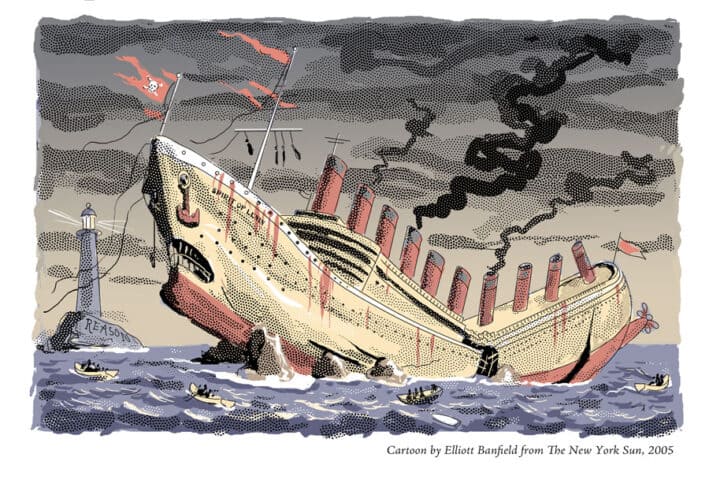

How did a sector long known for social services, education, and culture become one where some groups pursue, with little scrutiny, agendas at the far edge of our ideological and political spectrum? Gradually, then suddenly, as Ernest Hemingway once wrote. Laws and regulations designed to separate charity and politics have been twisted and stretched by smart lawyers, clever tax advisors, and ambitious political operatives.

Political Charity

Since robber barons created the first great foundations in the early 1900s, the public and Congress have been dubious about wealthy men’s claims to be altruistic. Rockefeller, Carnegie, Mellon, and others of that generation were suspected of using their generosity for devious purposes, including partisan politics.

The real story, however, begins in 1954, when Texas senator Lyndon Johnson was subjected to vicious attacks by a nonprofit group set up especially for that purpose. In response, he sponsored legislation that prohibited nonprofits from endorsing or opposing political candidates.

By the 1960s, wealthy individuals, their foundations, and the charities they funded became increasingly involved in social movements and efforts to empower minority citizens. Using foundations for self-interested purposes, like protecting the donor’s company from hostile takeovers or employing his feckless namesake as a highly paid chief executive, was among the concerns. But the big issue became partisan politics: how, specifically, charitable money and organizations were to be used in campaigns.

The 1967 mayoral race in Cleveland was the most prominent of these cases. After the Ford Foundation made a significant grant to a local organization for voter registration and mobilization efforts in the black community, Carl Stokes won the election and became the city’s first black mayor. Ford’s involvement in this and other voter registration efforts prompted the House Ways and Means Committee to hold a series of hearings where McGeorge Bundy, the foundation’s president, was the star witness. By all accounts, Bundy was unapologetic and arrogant, two attributes that do not go down well in the halls of Congress.

The hearings led to the Tax Reform Act of 1969 (TRA), which created a framework for regulating donors and charitable groups that is still in place, albeit severely frayed in its effectiveness. TRA established a grand bargain where donors and charitable organizations, operating as 501(c)(3)s—that is, entities named after the section of the tax code that spelled out their special status and its requirements—were greatly limited in their ability to engage in lobbying and election-adjacent activities. In return, donors would continue to receive tax deductions for their contributions to their foundations or directly to active charities.

Voter registration was a special target of the legislation. Foundations were allowed to support an organization only if it operated in at least five states, and had activities in those states that spanned more than one election cycle. Nonprofits were allowed to engage in some lobbying, but it was restricted to a small portion of their overall budget. At the same time, another category of nonprofits, 501(c)(4)s, were given much more latitude in terms of lobbying and engaging in election-related activities. Its donors, however, would not receive a tax deduction, and foundations were greatly restricted in their ability to support such organizations.

Today, it is fashionable to ascribe TRA’s election-related limits to racism and a fear of minority voting power. Indeed, some of the most prominent promoters of this legislation were also skeptical of the civil rights movement. Almost every prominent liberal in Congress, however, including George McGovern, Walter Mondale, and Ted Kennedy, supported it.

For a time, this compromise worked. After McGeorge Bundy’s counterproductive testimony, most foundation leaders were cautious about supporting anything that looked like lobbying or voter registration. Because foundations were the primary potential source of money, most election-related groups, almost all on the left, tried hard to meet the requirements and, hence, were almost all long-term, regional organizations. Most were modest and had limited contact with actual political advisers.

A Shell Game

The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 marked the beginning of a new era. His promise of radical change in Washington galvanized the Left. Smart, well-paid lawyers, including a few who had written the original regulations for the Tax Act, started advising both funders and activists on how to expand support for voter registration and mobilization. At the same time, environmental and other progressive groups were receiving advice on how to maximize their capacities to lobby Congress and the administration.

By the time Bill Clinton was nominated in 1992, registration groups were setting up camp on the edges of the Democratic National Convention. Foundations have to adhere to the rules noted earlier, but individual donors are free to support election-related projects that are short-term and geographically focused.

Perversely, there is even a tax incentive for the very wealthy to give directly to these nonprofits rather than through a foundation. TRA made a distinction between donations that would be put to work immediately by a nonprofit, which are fully deductible, and donations to foundations that would only be spent over a long period of time, which are only partially deductible. By giving your money directly, you could not only target specific House and Senate races in a given year, but also reduce your tax bill.

The other big innovation in the 1990s was the practice of setting up a 501(c)(4) closely affiliated with a 501(c)(3). Most organizations in this new category are innocuous entities, like fraternal organizations. Their attraction to politics stems from the fact that c4 groups have much more latitude in elections and lobbying. Although donations to the c4 are not tax deductible, money given to the c3 affiliate can be transferred to the c4 as long as the money is used for work in line with the group’s core mission.

The result is a shell game where money is given to a charitable organization, so the donor gets the tax benefit, and then some or all of it is transferred to the affiliate to undertake politics and lobbying. There are restrictions on these transfers, but this money can be used to cover rent, salaries, and other expenses not directly linked to politics or lobbying. Furthermore, neither the c3 nor the c4 must divulge their donors to the public. The IRS receives a list of contributors, but the rest of us can only guess who is putting money into the most politicized organizations.

Shell games become more effective, and insidious, as they grow more elaborate. Political Action Committees and similar entities, which exist solely to promote a candidate or a group of candidates, are organized under Section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code. Once linking c3 and c4 organizations was established, the next step was to create a 527 entity linked to the c4. Contributions are not tax deductible and money from the c3 cannot be transferred directly to the 527. However, the c4 is allowed to cover the fundraising and administrative costs of an affiliated 527. It is not hard to imagine how tax-deductible money entering the c3 group ends up helping a 527. Tax benefits, anonymity, and political clout are a powerful combination.

Within the past 15 years, the first of the subsequent innovations in tax-deductible political activity was the donor-advised fund (DAF). For many years, community foundations and similar charitable funds would establish accounts funded by a specific donor, who retained the right to advise the sponsoring community foundation concerning which charities his account would support. A DAF looks like a foundation, but contributions receive the full tax deduction. And, unlike a foundation, a DAF is not required to donate a minimum percentage of its assets each year. Though the community foundation must reveal the groups that receive money each year, these donations are not linked to a specific account.

Blurring the Lines

The revolution came when large financial institutions, like Goldman Sachs and Fidelity, created nonprofits to house DAFs and then undertook aggressive campaigns to promote the value and benefits of these giving vehicles. Billions have flowed into them in the 21st century. The companies have done well in the DAF business, but not without complications. Goldman Sachs has gone to great lengths to explain that “its” grant to the People’s Forum was not the company’s money, but rather funds from an undisclosed wealthy individual. In fact, several of these firms have now started to limit the freedom of donors to steer their money to any nonprofit and have blocked contributions to organizations that are involved in the current campus unrest.

A second development has been the creation of complex nonprofit entities that, in some cases, are a platform for DAFs and various c3 and c4 organizations. The Tides Foundation, along with its affiliates, is one of the most prominent examples. You can create a DAF there and use the money to support organizations that operate under the Tides banner (and its c3 tax status) or you can work with c3s and c4s in the Tides orbit on issues such as abortion, equity, Palestine, climate change, and, of course, “healthy democracy,” i.e., electing as many progressives as possible.

Arabella doesn’t host DAFs, but it does advise philanthropists on where their money will be most effectively applied. It also sponsors c3 and c4 organizations that it recommends to donors it advises. Arabella aggressively cultivates billionaire donors who want to influence politics and policy. One of its biggest donors, for example, is Hansjörg Wyss, a Swiss national with strong interests in American politics. Although it is illegal for foreign donors to support American political campaigns, contributions to c3s and c4s are allowed and can be given anonymously. Someone like Wyss can pour money into a c3 and watch it migrate to more aggressive political organizations without a trace.

Since 1969, we have gone from a system where there was a very sharp line between charity and politics to one where billions of donations can receive charitable tax benefits and then be moved around a very opaque network of politicized organizations. Regulators have largely given up on trying to trace the money and its uses. Even excellent investigative reporters, like Ken Vogel at The New York Times, are able only partially to outline where the money comes from, where it goes, and how it is ultimately used.

This blurring of the lines is not limited to George Soros and other left-wing donors. There are conservative entities, like the Marble Freedom Trust and Donors Trust, that mimic Arabella and Tides but on a smaller scale. As The New York Times reported in 2022, “15 of the most politically active nonprofit organizations that generally align with the Democratic Party spent more than $1.5 billion in 2020—compared to roughly $900 million spent by a comparable sample of 15 of the most politically active groups aligned with the G.O.P.”

By most indicators, that gap grew in 2020 when torrents of money poured into contested Senate races. In Georgia, Stacey Abrams put together the New Georgia Project which includes 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations as well as a 527 political action committee. Tax-deductible money going to the first group subsidized many of the activities of the latter two and did so with great effect as Democrats captured both contested Senate seats.

For the 2024 election, this trend has continued. The final numbers are not public but 140 foundations and individual donors agreed to make all or most of their “democracy” donations early in the election cycle. Pierre Omidiyar’s Democracy Fund has successfully pushed other left-of-center donors to speed up their contributions to voter registration, education, and mobilization projects. In addition, the Tides Foundation made a $200 million commitment to support voter mobilization among young people and communities of color. Over $1 billion was likely given to election-adjacent nonprofits.

The grand bargain of 1969 has broken down. Nonprofits say the right things to avoid being accused of partisan behavior, then undertake blatantly political work. One popular website, Blue Tent, has the goal of returning the House to Democratic control. It helps donors understand how to give charitable money to serve that end. It would be nice to say that this platform is a rare exception, but it is only one of many such sites that turn tax deductible money into political cash.

Our Broken System

What should be done about this situation? One obvious solution to this problem would be more rigorous enforcement of existing laws and regulations by the IRS and attorney generals at the state level. Advocates on both ends of the political spectrum, however, are reluctant to endorse this approach for different reasons. For progressives, any mention of greater scrutiny and enforcement is seen as a threat to civil rights and the empowerment of “least represented voters.” In other words, they know they have a good thing going and do not want to upset it. Conservatives fear politicized enforcement and believe it occurred during the Obama Administration. The responsible IRS official, Lois Lerner, was absolved of the charges that she denied conservative groups tax-exempt status, but her name is still a rallying cry against any attempt to bolster federal enforcement.

Another approach would be to exclude nonprofits involved in influencing policy and politics from the tax exemption. Politically, this is difficult for the obvious reason that the most politicized groups are the natural allies of politicians who count on them to promote their favored legislation and to help turn out the vote for their reelection. It would also create complicated definitional issues. Are think tanks policy advocates or simply the purveyors of ideas? If they house former elected officials who may one day run for office again, are they serving as a political launching pad?

Churches provide another challenge to cracking down on political behavior. Even though most donations to religious groups are not itemized and not deductible, churches are a third rail when policing nonprofit political activity. Black churches that host largely Democratic candidates and evangelical churches that invite largely Republican candidates all oppose any attempt to limit their political voices.

A simpler measure would require nonprofits engaged in politically adjacent work to disclose their major donors. Political candidates must disclose their donors because the public has a right to know who might influence elected officials, and to whom those officials are obligated. Donor transparency, an extension of this approach, would allow journalists and other watchdogs to scrutinize the money supporting elaborate voter registration and education efforts, as well as aggressive lobbying on important issues.

Here again, the Right and Left are united in their absolute opposition to greater transparency, fearing that donors to controversial groups could be targeted by opponents. This principle was established in the 1950s when the NAACP went to court to prevent public disclosure of its funders. Today, the loudest supporter of donor privacy is a trade association for conservative donors, which has pushed national and state legislation to prohibit public disclosure.

Without the political interest and will to address a broken and dysfunctional system, we can expect increasing amounts of money going through charitable channels to support political and lobbying activities. For many years, conservatives showed little interest in voter registration and mobilization on the grounds that low-turnout elections favored their candidates. This view is now changing, and conservative platforms modeled on Arabella Advisors and the Tides Foundation are now being formed to move money into nonprofits designed to support election-related activities.

While it may be positive that conservatives are finally waking up to the challenge posed by politicized nonprofits, one should be skeptical that this move will be successful. The record of American billionaires’ personal and foundation donations makes it hard to believe that even a rough parity between progressive and conservative nonprofits will ever be realized.

Is there any hope for reform? Some politicians, like J.D. Vance, have shown an interest in pushing for major reforms of foundations, endowments, and the larger nonprofit sector. His criticisms have been dismissed as rank populism by conservative groups and as purely partisan and ideological by the liberals. Nonetheless, his attacks on big foundations, like Gates and Ford, and his questioning of why Harvard and Yale are allowed to amass huge investment portfolios, have gathered attention by reform-minded critics on the left and right.

Other politicians, including Bernie Sanders, recognize how wasteful and corrupting the current system is and may be willing to work with Vance to achieve the type of overall reform that occurred in 1969. Then, the successful political coalition was diverse and complicated, but united in wanting to curb philanthropy’s ability to engage in elections and policymaking. The legitimacy of our charitable sector and the integrity of our political system may well hinge on a recognition that the current system is fundamentally flawed and broken.