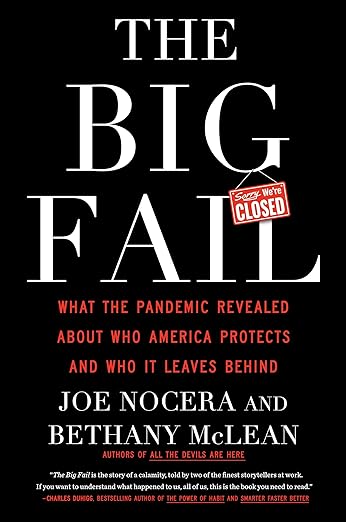

Books Reviewed

It’s still hard to believe that Americans recently lived through a period in which executive officials, with no legislative involvement, ordered churches, shops, and schools to be closed, forced Americans to hide their faces behind masks, and even demanded that they be fired for not taking experimental vaccines. Yet that was life in America—at least in many states—throughout much of 2020, 2021, and even 2022.

Now, an Olympiad removed from the arrival of the apparently human-enhanced Wuhan virus on our shores, it seems clear that the lockdown and mask regime that took root in response to the virus was among the worst public policy debacles on record. How did we let it happen, and how do we keep it from happening again?

Journalists Joe Nocera and Bethany McLean, authors of The Big Fail: What the Pandemic Revealed About Who America Protects and Who It Leaves Behind, are critical of the lockdowns—largely because of their unequal effects on rich and poor, Zoom workers and blue-collar workers. They rightly warn that when “the public health establishment” reflects on the pandemic from today’s vantage point, it thinks, “If only we had masked up more and earlier. If only we had locked down harder and longer.” In other words, if such people are in charge again the next time there’s a pandemic, or even during a worse-than-usual seasonal virus, their authoritarian and data-denying impulses will be back on full display. One lesson learned must be that we should not leave them in charge.

The approach that the public health establishment championed was truly radical. “Prior to the Wuhan outbreak,” write Nocera and McLean, “no country in history had attempted to fight a pathogen by locking down its citizens for months at a time.” Then China locked down Wuhan. Following the Communists’ example, the Italian government locked down Italy. This thrilled Neil Ferguson, head of the infectious disease department at Imperial College London, whose faulty model helped spur panic over COVID-19. Ferguson had never thought lockdowns would fly outside of authoritarian regimes. “And then Italy did it,” he said, “and we realized we could.” The land of the free and the home of the brave, sadly, would prove to be no exception.

Ferguson was soon found to be prioritizing a tryst with a married (not to him) female climate activist over obeying the lockdown rules he had helped bring about, write The Big Fail’s authors, thereby breeding “the same kind of resentment toward all the we-know-what’s-good-for-you elites that gave Britain Brexit and America Donald Trump.” This and other examples of hypocrisy, however, didn’t stop the lockdowns on either side of the Atlantic. Nocera and McLean write that the lockdowns were “a giant experiment” that wrought “devastating social and economic consequences.”

***

Nocera, a former op-ed columnist for The New York Times, and McLean, a contributing editor for Vanity Fair, are hardly coming at these matters from a movement-conservative perspective. With their favoring of left-leaning sources; criticism of elites, globalization, and private-equity firms; and willingness to question the general leftist narrative, they come across as independent-minded liberals. In tandem, they sound like a vax-enthusiast version of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. While not without its blind spots—especially on masks—The Big Fail is a readable and relatively thorough account of our disastrous refusal to adhere to science, common sense, law, and all prior precedent when confronted with the worst pandemic in a century.

Although Nocera and McLean recognize that the public health establishment repeatedly failed to look at hard evidence or consider the costs of its lockdown agenda, the authors aren’t quite willing to recognize just how politicized such “experts” were. They quote a Trump-skeptical doctor as asking in the early days of the pandemic, “Is what I’m reading actually coming from the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], or is it politically motivated?” The answer, likely, was yes—it was from the politically motivated CDC.

Of course, it was the government leaders who let the public health establishment reign. President Trump initially tapped his political appointee, Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar, to lead the White House Coronavirus Task Force. After an HHS career employee contradicted the White House in late February 2020 by publicly predicting that COVID-19 would affect large portions of the population, Trump benched Azar as head of the Task Force and installed Vice President Mike Pence. Concurrently, the White House added longtime public health bureaucrat Deborah Birx to the Task Force as its coordinator.

***

Nocera and McLean claim that Birx—who’d known another high-ranking career public health bureaucrat, Anthony Fauci, since the 1980s—was “highly regarded” but unfortunately “had little or no power” on the Task Force, as “politics kept getting in the way.” But this contradicts the authors’ subsequent claim that less than three weeks after Birx’s arrival the White House announced “a series of federal guidelines, mostly the ones being advocated by Fauci and Birx.” These guidelines—to close schools and to avoid restaurants and gatherings of ten or more people—marked the beginning of the lockdowns in the United States. Just three days later, California governor Gavin Newsom transformed the guidelines into mandates, imposing the first statewide lockdown.

Nocera and McLean’s assertion that Birx was sidelined due to politics is even more strongly contradicted by Scott Atlas, whom Trump added to the Task Force in summer 2020. In A Plague Upon Our House (2021), Atlas maintains that Birx was completely in charge of providing medical input both to the Task Force and to Trump’s mostly “amateurish” communications team. Atlas’s book isn’t nearly as polished or well edited as The Big Fail (probably because major publishing houses wouldn’t accept a work from someone so opposed to the official narrative), but it’s full of gems afforded by his insider vantage point. Indeed, The Big Fail and A Plague Upon Our House complement each other nicely.

Fauci and Birx were allied on the Task Force with a Trump political appointee, CDC director Robert Redfield. This troika, says Atlas, “shared thought processes and views to an uncanny level,” never challenged one another, and “virtually always agreed.” He says none ever brought scientific publications into meetings, discussed COVID-19 research, showed familiarity with clinical medicine, or engaged in critical thinking, preferring instead to remain willfully ignorant.

***

Atlas observes that none of these three was a health policy scholar, which meant that “no one with a medical science background who also considered the impacts of the policies was advising the White House.” (Also, neither Fauci nor Birx was an epidemiologist, even though then-Fox News host Chris Wallace once exclaimed about Atlas, “He’s not an epidemiologist!… Follow the scientists! Listen to people like Anthony Fauci…[and] Deborah Birx!”) Fauci, Birx, and Redfield all had backgrounds in the AIDS world, which was a good training ground for learning how to deceive the public. Fauci had claimed that HIV/AIDS could be transmitted by “routine close contact, as within a family household,” after it was known that the virus was transmitted almost entirely via intravenous needles and unconventional sexual activity. Atlas writes that in the 1980s Birx had worked in Fauci’s lab, then been a research assistant for Redfield, then, decades later—when holding a high-level position under President Obama—helped funnel millions of dollars to Redfield’s lab. Atlas dryly observes, “This was not exactly a well-rounded team of independent, diverse voices for designing health policy for this pandemic.”

Atlas, who’d been the chief of neuroradiology at Stanford University Medical Center before becoming a health policy scholar at the Hoover Institution, was brought in to be a personal advisor to the president and a dissenting voice on the Task Force—likely because Trump had seen him on TV. The two got along well, and they parted after Election Day on good terms.

Atlas expresses frustration, however, over Trump’s refusal to take charge. He describes a remarkable level of buck-passing in the White House, to the benefit of the career bureaucrats. Atlas writes that when he tried to convince the president to overrule Fauci and Birx—whose lockdown policies were being “implemented in almost every state”—Trump replied, “You’ll have to convince my son-in-law.” When Atlas approached Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner implausibly claimed that Birx is “100-percent MAGA” and said, “Talk to the vice president; he runs the Task Force.” As for Pence, Birx “knew the VP had her back, often echoing her words.” In one Task Force meeting, Atlas argued against Birx’s proposal for more mass testing, maintaining that this approach was pointless, counterproductive, and demoralizing, and that it detracted from protecting the truly vulnerable and letting others get on with their lives. Pence politely let Atlas finish, proceeded to the next agenda item, and at the end of the meeting said, “So we will make sure we increase the testing.”

***

Atlas sums up this unfortunate state of affairs by explaining that “the administration had elevated a couple of government public health bureaucrats to effectively be in charge of public policy” and then “failed to correct that mistake.” The result was “one of the greatest public health failures in history.”

This failure of leadership would prove very costly to the country—and to Trump’s reelection prospects. One wonders how things would have played out had Trump periodically given the sort of sober yet reassuring speeches from behind the Oval Office desk that Ronald Reagan, John F. Kennedy, or Franklin Roosevelt would have relished giving in Trump’s circumstances. Such speeches could have focused on telling Americans what we knew, what we didn’t know, and where we were going—while emphasizing that most people got mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19, that natural immunity was real, and that life should go on as usual aside from the need to be diligent about protecting the most vulnerable. Instead, Fauci was permitted to appear on television ad nauseam conveying an entirely different message—even as the Trump Administration barred many other officials from giving TV interviews—while the troika of Birx, Fauci, and Redfield kept steering the country toward masking and lockdowns and cultivating fear. In one Task Force meeting, perhaps six months into the pandemic, Atlas asked Fauci, “So you think people aren’t frightened enough?” Fauci replied, “Yes, they need to be more afraid.”

The anti-Fauci was Donald A. Henderson, an epidemiologist who was the director of the World Health Organization’s successful efforts in the 1960s and ’70s to eradicate smallpox. Nocera and McLean observe that Henderson counseled humility and an appreciation of society’s complexity in the face of a public health crisis. A decade before his death in 2016, Henderson and three colleagues wrote, “Experience has shown that communities faced with epidemics or other adverse events respond best and with the least anxiety when the normal social functioning of the community is least disrupted.”

During COVID, America profoundly departed from this tried-and-true approach. But why? As Nocera and McLean wondered, was the goal to “flatten the curve,” or to wipe out the disease? “Even if the lockdown did slow the disease’s progression,” they ask, “what would happen when the lockdown was lifted? In other words, what was the endgame?” As is also true with most of our post-World War II military interventions, that answer was never really provided.

***

Highlighting studies suggesting that the lockdowns did not reduce excess mortality, Nocera and McLean note many of the reasons why: “increased opioid use, a surge of alcoholism, a higher murder rate, and deaths related to the difficulty of getting hospital care for anything other than COVID-19.” But though it’s not at all clear that lockdowns saved lives, it’s quite clear that they severely compromised people’s quality of life, especially for those outside of the Zoom and Uber Eats class. By fall 2020, even the World Health Organization’s special envoy on COVID-19, David Nabarro, was saying, “We…do not advocate lockdowns as a primary means of control of this virus.” Thanks to lockdowns, he said, “we may have a doubling of poverty.” Yet the lockdowns continued.

Independent shops and restaurants took a particular beating. Nocera and McLean write that Governor Newsom’s lockdown policies in California “seemed almost intentionally designed to hurt small businesses.” They report that by fall 2020, when Newsom imposed his second wave of lockdowns—which didn’t prevent him from dining at the posh French Laundry restaurant, sending his own children to an in-person private school, and keeping his own winery open—the number of business closures in California had risen from 19,000 in the early summer to 40,000, with half of those being permanent. In Los Angeles County alone, they write, 15,000 businesses closed. In New York City, where Mayor Bill de Blasio shared Newsom’s fondness for tyrannical mandates, more than 6,000 stores and restaurants permanently closed—an astounding number. Meanwhile, many big businesses and the investor class flourished. Apple, which makes 98% of its iPhones in China, saw its market value more than double from mid-March to the end of 2020.

Likewise, after falling by more than one-third in less than five weeks at the start of the pandemic, the S&P 500 hit an all-time high in August 2020—hot on the heels of the worst quarterly drop in gross domestic product ever. Nocera and McLean write that this magic trick was made possible only through an “extraordinary” and unprecedented intervention by the Federal Reserve, which bought $1.1 trillion in Treasury securities in less than a month, effectively printing money. The authors appear to admire the Fed’s quick actions to save the economy but also think these caused lasting inflation and economic inequality. Then came the $2.2 trillion CARES Act. This was intended to provide crucial help for desperate small businesses, but the Los Angeles Lakers also got $4.6 million, outright theft was rampant, and independent restaurants were about the last to get any of the assistance. This federal largesse—which spurred not only inflation but also the two worst inflation-adjusted deficits in American history—was necessitated by the lockdowns.

***

Florida, of course, stood in marked contrast. Nocera and McLean note that while Birx, Fauci, and Redfield were calling the shots on the White House Task Force, Florida governor Ron DeSantis formed his own hand-picked force. Among others, DeSantis relied on Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya and Swedish-born Harvard epidemiologist Martin Kulldorff, two of the three authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, which, issued in the fall of 2020, was perhaps the most prominent public statement against the lockdowns. Atlas, who also advised the governor, says DeSantis “personally sought out, critically analyzed, and truly understood every important detail about the pandemic.”

DeSantis was thus well-armed to make Florida the model of an open state, while also doing more than blue-state governors to protect patients in nursing homes, the most dangerous place during the pandemic. Atlas writes that DeSantis set up COVID-only facilities and forbade nursing homes from taking patients with COVID-19 who were discharged from hospitals—the opposite of New York governor Andrew Cuomo, who mandated that nursing homes admit COVID-positive patients, with tragic results.

The Big Fail’s authors observe that DeSantis was treated “like a piñata” by the press for daring to defy the “experts.” Nocera admits he was one of those wielding the stick, as he wrote a series of columns in 2020 about DeSantis’s COVID-19 policies. After predicting that Florida’s day of reckoning would come, he says he “learned the hard way” not to jump to conclusions based on short-term data. (He and McLean, however, cannot resist criticizing DeSantis for trying to remake the New College of Florida by replacing its board with “cronies” like Christopher Rufo and Charles Kesler.)

Nocera and McLean note that though Florida and California did about equally well in avoiding COVID-19 deaths, Florida had barely over half the unemployment rate of California, far fewer business closures, and many more business start-ups. They also observe that DeSantis championed giving legal cover to doctors who departed from the medical consensus just a few months after Newsom had signed legislation to punish doctors who spread COVID “misinformation.” The authors side with DeSantis, noting that such “misinformation” has often turned out to be true.

***

Nocera and McLean are especially critical of school closures. They note the declining reading test scores (2022 scores fell to 1992 levels), the number of kids who had to fend for themselves while their parents worked (not on Zoom), and the shoddy nature of “remote learning.” They observe that “the teachers’ union fought to keep teachers away from the classroom” and that the Biden Administration’s CDC basically let the teachers’ union write the agency’s return-to-school guidelines. The authors add that “in the fight over schools” it was “blue state Democrats who valued their political affiliation over common sense—and even over their pre-pandemic pretensions about protecting the underprivileged.”

Both The Big Fail and A Plague Upon Our House argue that kids were less apt to spread the virus than adults were, with the former volume noting that the infection rate “for teachers in Sweden, where schools never closed, was no higher than the infection rate for teachers in Finland, which had closed its public schools.” Maybe the best illustration of the foolishness of closing schools when confronted with a virus that largely spared children was provided by Bhattacharya in his communications with Nocera and McLean. The doctor described a newspaper article he’d seen that featured a photograph of two children who were about seven or eight years old:

Their parents had dropped them outside a Taco Bell with what looked like Google Chromebooks…. They were sitting on the sidewalk doing schoolwork because that was the only place they could get free Wi-Fi. Their parents weren’t there, because they had to go to work.

This is perhaps the perfect picture of our insane COVID-19 response, especially if the kids were wearing masks.

Though Nocera and McLean are willing to depart from the Left’s thinking on lockdowns, their neglect of conservative sources outside of The Wall Street Journal leaves them largely blind on masks. They frequently cite The Atlantic but never once mention City Journal, a counterpart of sorts on the right, which has published what is probably the best collection of scientifically rigorous anti-masking articles. Nor do they show any awareness of the arguments against masking that go beyond science—those based on masks’ profound impoverishment of human interaction—such as were made in the CRB’s pages (see “The Masking of America,” Summer 2021). Instead, they spend almost an entire chapter lamenting the lack of masks early in the pandemic for health-care workers.

***

Only in the book’s introduction, which was pretty clearly written last, do Nocera and McLean start to see the light on masks. There they discuss the 2023 mask review by the Cochrane Library, the most trusted source for evaluating randomized controlled trials, which in turn are the gold standard of medical evidence. Cochrane found that when it comes to providing protections against viruses, wearing a mask “probably makes little or no difference…compared to not wearing” a mask, and that using an N95 “compared to” a surgical mask “probably makes little or no difference” as well. What Nocera and McLean don’t realize is that this language was contained verbatim three years earlier in Cochrane’s 2020 review.

A German study during COVID-19 found that those who wear masks for more than five minutes at a time breathe in 35 to 80 times the normal levels of carbon dioxide—far above the levels permitted on navy submarines. In short, mask wearers are basically poisoning themselves—particularly those wearing N95 masks. Masks weren’t designed to stop the spread of viruses. Rather, surgical masks were designed to keep medical personnel from infecting patients’ open wounds, while N95s were designed to protect against dust, fumes, and smoke. When used against viruses, they function as a totem—and as a clear symbol that one values neither social interaction nor scientific rigor. In that same spirit, Scientific American, which dates to 1845 and touts itself as “the oldest continuously published magazine in the United States,” ran an article last year arguing that scientists should prioritize “reality” over scientific “rigor,” since the latter doesn’t support the wearing of masks.

The Big Fail argues that the debate over masks “was a symbol of one’s politics,” as “pre-existing bias trumped fact-finding and scientific inquiry.” Yet the best the authors can muster in terms of breaking free of their own politics is to claim that after Cochrane’s 2023 review was published “we were back where we started: we still didn’t know whether masks work.” Actually, after 16 randomized controlled trials on masks, we do know that there’s no good evidence that they work—the usual standard for rejecting a medical intervention—and plenty of evidence that they have side effects that would never be tolerated in a drug.

***

Atlas rightly finds it laughable that Birx told him the best evidence that masks work is a “study” from a hair salon in Missouri—which lacked a control group, didn’t test whether most people involved had gotten COVID-19, and thus revealed essentially nothing. Redfield, meanwhile, ludicrously said during congressional testimony that “if every one of us did it [wore a mask], this pandemic would be over in eight to twelve weeks.” These (along with Fauci) were the public health officials whom the Trump White House empowered to guide us through the pandemic.

As for vaccines, both books agree that Operation Warp Speed (OWS), the program to develop and manufacture a COVID-19 vaccine as quickly as possible, was a great success. Atlas says that “it will be very difficult to deny” its accomplishments, while Nocera and McLean write, “For all the things government did wrong during the pandemic, developing the vaccines by working in tandem with private industry was something it got very right.” Led by Azar (back from the dead) and combining scientific expertise (under longtime vaccine developer Moncef Slaoui), army-style logistics (run by former Army logistics officer and retired general Gus Perna), and a whole lot of money (Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchen squirreled away $10 billion from the CARES Act and gave it to OWS without explicit congressional authorization), it does appear to have been an effort reminiscent of the public-private partnerships that helped America win World War II. The Big Fail’s authors note that Europe wasn’t able to make a vaccine available until months later. Many vulnerable Americans’ lives were presumably saved in the interim.

The two books disagree, however, about the motivation for announcing the vaccines’ successful trials just six days after the 2020 presidential election—rather than, say, a week earlier. After noting that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) introduced delays in the approval process not long after Trump told Geraldo Rivera that the vaccines might be ready by Election Day, Nocera and McLean approvingly write, “The delay appeared to be an effort to prove to the public that the vaccine process was not going to be influenced by politics.” Conversely, Atlas believes that “there were some delays that were not easy to explain if not for politics.” He says Stephen Hahn, Trump’s political appointee as FDA commissioner, “unexpectedly introduced…a requirement of sixty days between half the test subjects receiving the dose and a safety assessment of the mRNA vaccines in trials.” Atlas writes, “I was informed by a highly experienced vaccine expert who had worked with the FDA and CDC for years that this exceeded the standard forty-two days typically needed to assess safety issues.” Though the 60-day requirement could have been legitimate—especially given the vaccines’ experimental nature—it is hard to believe that mere coincidence can explain how the timing lined up just six days too late for Trump.

***

Shortly after taking office two months later—and despite initially having been vaccine skeptical—President Biden and his administration began acting as if the president’s son Hunter held a majority stake in Pfizer and Moderna. Biden’s newly installed CDC Director Rochelle Walensky told Rachel Maddow that data suggests that “vaccinated people do not carry the virus” and “don’t get sick.” This wild claim was exposed as utter nonsense in the months to come, such as when three-quarters of those infected during a COVID-19 outbreak in Provincetown, Massachusetts, had previously been vaccinated.

Nevertheless, the Biden Administration kept pushing the vaccines on nearly everyone, including young men—for whom they brought about an increased risk of myocarditis, as Nocera and McLean note—and young children, for whom the virus was only about as deadly as the common flu. Keep in mind that these were experimental vaccines; as Nocera and McLean observe, “This was the first time mRNA had ever been used in a drug.” Yet Biden told his fellow Americans in a national address that he was “frustrated” with the unvaccinated and could “understand” the “anger” toward them. He told those with children, “They get vaccinated for a lot of things. That’s it. Get them vaccinated.” To all Americans, he said in reference to his administration’s mask mandates on planes (something the Trump Administration had never imposed), “If you break the rules, be prepared to pay. And by the way, show some respect.”

A federal judge soon struck down that kingly mask mandate, as did another regarding Biden’s decree that federal employees—almost none of whom was then being asked to show up for work in person on a routine basis—must get vaccinated or else be fired. Most notably, the Supreme Court struck down Biden’s combination vaccine/mask mandate, issued through the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which applied to 84 million private-sector workers. In a concurring opinion, Justices Neil Gorsuch, Samuel Alito, and Clarence Thomas reminded Biden that under our separation of powers and federalism, laws are made by Congress or the state legislatures, not by the president or executive agencies.

***

Nevertheless, vaccine passports (requiring the sorts of IDs that are supposedly anathema to voting rights) were very much in vogue in many large cities—with the exception, again, of Florida, where vaccine passports were forbidden. Biden even banned unvaccinated tennis great Novak Djokovic from playing in the 2022 U.S. Open—despite the fact that he’d played in the 2021 event without being vaccinated and that he’d had COVID-19 at least twice and therefore surely had natural immunity. In another example of New York City craziness, unvaccinated Nets basketball star Kyrie Irving was allowed to watch from the stands during games, but he couldn’t play.

By the summer of 2022, the Pfizer-Moderna-Biden Administration alliance had paved the way for six-month-old babies to be given the experimental vaccine. In August 2021, the Biden Administration announced—before the FDA advisory committee had weighed in—that it would soon be rolling out booster shots. After the advisory committee subsequently recommended boosters only for seniors and the immunocompromised, the FDA ignored its own advisory panel and green-lighted the shots. Nocera and McLean report that when so-called bivalent boosters (designed to protect against both original COVID-19 and Omicron) were then introduced, Pfizer’s version was approved on the basis of a test conducted on eight mice. Soon the CDC was recommending the bivalent booster for everyone over age five.

***

Both The Big Fail and A Plague Upon Our House are helpful in reviewing the traveling circus of human folly that we all witnessed during the COVID-19 era. Joe Nocera and Bethany McLean haven’t yet fully made the transition from the cave into the light, but they deserve much credit for questioning many aspects of the mainstream narrative. Building on their valuable overview, as well as on Scott Atlas’s illuminating insider account, here are my top five lessons from one of the most extraordinary episodes in American history:

- Don’t defer to public health “experts.” Such “experts” are at best advisors who often have a very narrow view of human affairs; they should certainly not be the deciders. Moreover, public health officials, many of whom aren’t exactly the best and brightest (see Fauci, Birx, and Redfield), love public health interventions. Atlas quotes Winston Churchill’s wise observation: “Expert knowledge is limited knowledge.”

- Don’t shut down society. The cost of the lockdowns was extraordinary and is ongoing. And it’s not at all clear that these draconian and unrepublican measures succeeded in reducing the number of deaths in the least.

- Focus on protecting the most vulnerable. Based on CDC and U.S. Census Bureau stats, those aged 75 and up were more than 1,100 times as likely to die of COVID-19, per capita, as those under age 18. When somebody is more than 1,100 times as vulnerable as somebody else, one shouldn’t treat the two the same, let alone place more mandates on the far-less-vulnerable set.

- Don’t impose mask mandates—or senseless vaccine mandates. The West has always valued showing the face. That’s the main way that we identify each other as unique human beings with God-given rights, rather than looking like faceless subjects. A citizenry that forgets the importance of the face is also likely to forget the importance of certain unalienable rights. It makes no sense to mandate masks in any event—as the best available evidence suggests they don’t work—or to mandate vaccines, especially experimental ones, that don’t prevent a virus’s spread.

- Don’t let executives rule like kings. Executives—whether the president or governors—should focus on communicating, not mandating. They should share what is known, reassure when possible, and help instill courage rather than cowardice. In a republic, executives are supposed to carry out the laws passed by legislatures, not unilaterally make and enforce their own quasi-legislation. In his Second Treatise of Government, John Locke writes that a country’s very form of government is determined by who exercises the legislative power. A “Society,” he writes, “may put the powers of making Laws…into the hands of one Man, and then it is a Monarchy.”