Books Reviewed

If I told you belief in the American Dream stands today at 70%, would you believe me? It’s true. You might raise an eyebrow because you’re aware the American Dream is made possible by our glorious institutions, none of which is looking so spiffy, except maybe the military and small business. As for the others, according to Gallup only 25% of Americans express “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of trust in big business, 30% in banks, 36% in the medical system, and 11% in Congress. Having faith in the American Dream while scoffing at its constituent parts seems like being blithe about putting an astronaut on Mars while scoffing at physics, engineering, and courage.

Historian James Truslow Adams coined the phrase “the American Dream” in his 1931 book The Epic of America. His framing remains serviceable: “a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.” The American Dream assumes freedom, fairness, meritocracy. A “European Dream” would be a vastly different thing, in the past involving feudalism and serfdom and today a lot of bowing to the wishes of Angela Merkel. Europe is about knowing your place. America, gloriously, is about creating any damn place you like—if you can get away with it.

* * *

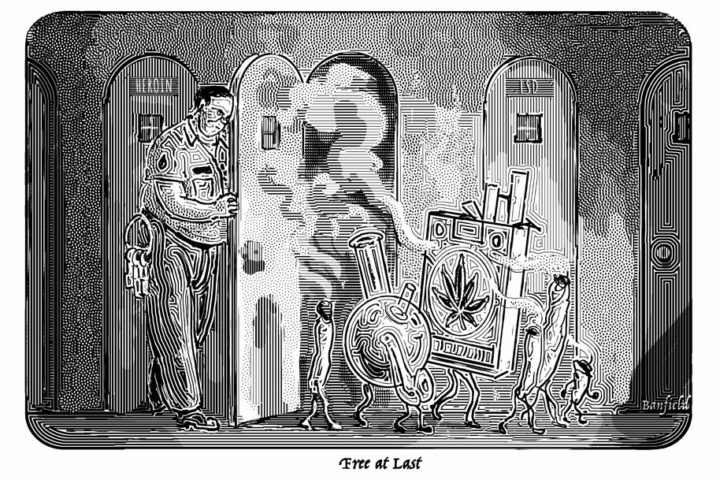

As Paul Cantor observes in Pop Culture and the Dark Side of the American Dream: Con Men, Gangsters, Drug Lords, and Zombies, that “if” has fascinated our writers going back at least to Mark Twain. Cantor’s latest is a lively, astute, and infectiously enthusiastic consideration of works ranging from Huckleberry Finn to today’s television zombie sensation The Walking Dead. The connective tissue linking these works, via the intervening subjects of W.C. Fields’s comedies, the Godfather films, and AMC’s Shakespearean drug tragedy Breaking Bad, may not immediately be obvious, but Cantor proves it’s there. He does a brilliant job sussing out how his artists raise important and unsettling questions about the credibility, durability, and internal tensions of the American Dream. I’d say Cantor’s subjects “interrogate” or even “subvert” the American Dream—but that would make the book sound more academic (and boring) than it is. Cantor holds a chair in the English department of the University of Virginia, but you’d never know it. This is a compliment.

Consider Huckleberry Finn, a novel about liars, mountebanks, and flim-flammers written under a phony name by a judge’s son who dressed like a Southern plantation owner. The Duke and the King, lowlifes with fancy, made-up European titles of nobility, capitalize upon the American Dream’s wide-open possibilities. Freed from Europe’s rigid social hierarchies and even from any particular chunk of land, Americans can create new selves. But the flip side is that almost nobody, in Twain’s eyes, can be trusted. European living is anchored to a village in which everyone knows everyone; American living glides along the rollicking, fertile, ever-changing Mississippi—a dynamic, vigorous, competitive environment of ever-shifting status. Fortunes are won or lost, sometimes in accordance with merit, sometimes not. In the words of V.S. Pritchett, “scroungers, rogues, murderers, the lonely women, the frothing revivalists, the maundering boatmen and fantastic drunks of the river towns” are “the human wastage that is left in the wake of a great effort of the human will…. These people are the price paid for building a new country.” Twain wouldn’t have it any other way—he thinks European aristocracy at least equally fraudulent—but there is a lot of crookedness along that river. Out on the Mississippi, far from the established cities of the East, institutions are fragile, and opportunities for exploitation everywhere. “The democratic world Twain portrays in Huckleberry Finn is filled with impostors,” Cantor writes. They’re self-made men in more ways than one. Grifters assume European titles because it works on their marks, who at some level long for the certainties of the Old World.

* * *

That tension is at the heart of The Godfather and its (first) sequel, both of which Cantor explicates beautifully. (He disdains Part III and excludes it from his analysis.) Francis Ford Coppola’s films are a mischievous look at how Old World thinking pollutes the new when our ideals fail. With four devastating words—“Who’s being naïve, Kay?”—Michael Corleone spoke for every cynic, relativist, and outright gangster who holds that senators are no different from Sicilian dons, even when it comes to disposing of enemies. If our most esteemed tribunes and the institution they stand for don’t play by the rules, why recoil at the Corleones? It’s self-serving for Michael to believe this but, as Cantor points out, Coppola seems to believe it too: perhaps the most rebarbative character in either film is the corrupt senator Pat Geary in The Godfather, Part II. At least the Corleones uphold the sanctity of family and honor, and can make a nice red sauce.

Cantor’s chapter on the Corleones doesn’t break new ground (last year Jonah Goldberg’s Suicide of the West offered a similar take) but it’s a marvelous account of how the rise and fall of Vito and Michael reflects the breakdown of the American Dream. The first words spoken in The Godfather are “I believe in America,” by a petitioner named Amerigo Bonasera—literally, “Goodnight America.” Bonasera’s request for old-world-style revenge against the men who attacked his daughter begins a detailed indictment of the corruption of the American spirit. Michael, the Ivy League golden boy, was supposed to become the first truly New World Corleone as he completed the transition into lawful business dealings and reached a governor’s mansion or the Senate. Instead he followed Bonasera’s lead back into vendetta culture, at the cost of his soul and eventually even his daughter. Released three months before the Watergate break-in, The Godfather is of a different, less cynical era. Yet it was ahead of its time in beguiling its audience with the notion that, if rules were being flouted everywhere, rules were for suckers.

* * *

One such sucker who has had enough is Walter White, the high-school chemistry teacher in Breaking Bad. Walter epitomizes both the middle-class fear that increasingly desperate striving is required just to stay in place as well as the modern family man’s daily humiliation. Walter works part-time in a car wash to pay for his son’s medical expenses, and for this he is mocked by his ungrateful students. He embodies the collapse of faith in institutions: public education (his students are punks and don’t pay attention), the medical establishment (he is staggered by bills associated with his son’s cerebral palsy), and Silicon Valley (he helps found a startup that becomes a huge business yet nets only $5,000 from the venture). By discarding all norms and turning to the drug trade, Walter becomes a caricature of American entrepreneurship and masculine bravado, a middle-class fellow who realizes his fullest stature as an individual by the only means available to him. The story of Walter White is that broken systems can be the cause as well as the effect of broken people. When the American Dream’s promise is seen as null and void, bad things happen.

* * *

Cantor’s final chapter asks whether our focus on material betterment has trapped us on a hedonic treadmill and distracted us from an earlier conception of the ideal American existence—rugged self-sufficiency in small communities of like-minded folk. Perhaps we just need a hearty zombie plague to remind us.

Small, tightly-knit, heavily-armed bands of survivors roam a desolate zombie-ravaged landscape in The Walking Dead, AMC’s sci-fi neo-Western. “A disaster in material terms,” Cantor argues, “turns out to have some good results in emotional terms…. [F]amily bonds grow tighter and people learn who their real friends are.” Maybe the zombies are a warning about a brainless, soulless existence—the latest incarnation of T.S. Eliot’s hollow men. They also serve as an amusing allegory of the red-state/blue-state cultural rift. A devastating satiric series interlude takes place in a cosseted Beltway burb in Alexandria, Virginia, where the roaming band of coarse gunslingers takes shelter in a gated community among a coterie of clueless gentry liberals who demand that all guns be locked away “for safety.” As in other “Redneck Renaissance” TV shows—Duck Dynasty, Mountain Men, Ice Road Truckers—The Walking Dead glories in practical solutions over vacuous progressive shibboleths. “[T]he spirit of the Wild West triumphs over the spirit of Beltway liberalism,” Cantor writes.

The series plays on our fears about the failure, if not outright malice, of the federal government: the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta cooks up a zombie plague then protects only itself against the consequences. Cantor may be right to detect a submerged libertarian hope in the carnage: Hey, the country may have been overrun by zombies, but at least we got the federal government off our backs. If a little bit of apocalypse is the price we need to pay for restoring family and federalism, I’m all ears.