We must walk in new ways, or we can never encounter our enemy in his devious march.

—Edmund Burke

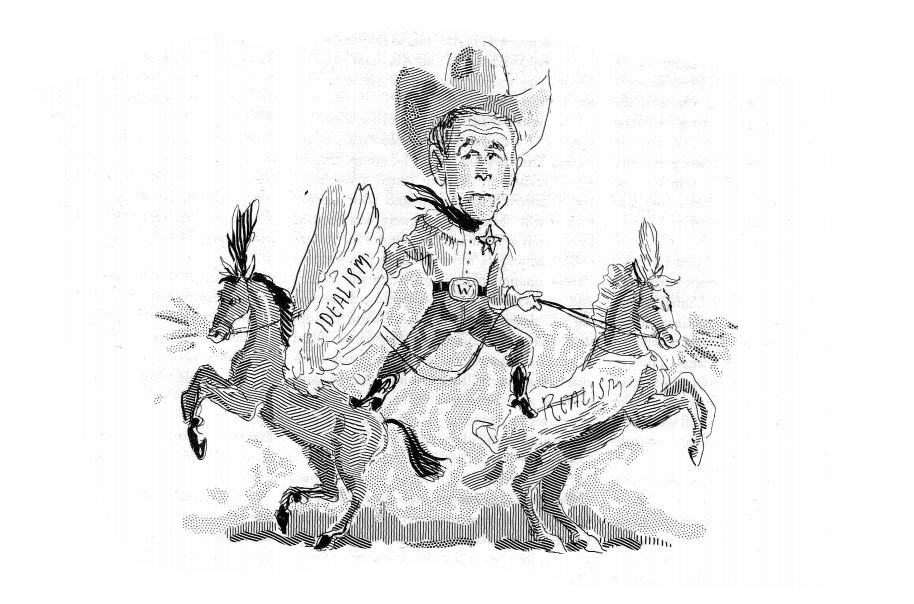

No one seems to know quite what to make of the foreign policy of George W. Bush. Realists attack him for his excessive idealism, but idealists want nothing to do with the man or his policies. Most liberals view the Bush policy as arrogant or hypocritical or cynical, or all of the above. For certain conservatives, the Bush policy in its universalism is an ugly stepchild of the French Revolution. Meanwhile, his supporters often do not agree on what they are supporting. Some characterize his policies as a kind of idealism; others, taking a contrary view, describe his policies in terms of a higher realism or natural law. As for intellectual sources, supporters and critics have variously invoked Thomas Paine, John Quincy Adams, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Leo Strauss—even Jesus Christ.

The Bush Doctrine, in truth, defies easy definition or classification. The twin pillars of Bush’s policy—aggressively spreading democracy, while forcefully preempting emerging threats—are as unfamilar to recent American foreign policy as their combination is unsettling. As a result, his overall strategy has been at times grossly misunderstood and caricatured. To label Bush and the other key architects of his policy “neocons” is to substitute polemics for serious analysis. Bush has transformed American foreign policy, at least in terms of its contemporary practice, and so our first step should be to understand what he has accomplished.

We might begin by considering the ways he has diverged from, even upended, the two main schools of foreign-policy making in the United States—idealism and realism. Both in terms of the principles he has set forth, and the policies he has implemented, Bush has pretty much abandoned these two long-standing approaches. By bringing the Bush policy into fuller view, and clearer focus, we shall be in a better position to consider possible problems and complications. What’s not entirely clear is whether Bush’s new thinking has adequately taken account of the possible constraints imposed upon it by America’s own polity as well as certain deeper political realities.

No Ordinary Idealist

Realist and conservative critics accuse Bush of being a reckless Wilsonian. In his rhetoric, he does frequently reach Wilsonian heights, as when in his Second Inaugural he declared America’s “ultimate goal” to be “ending tyranny in our world.” Nonetheless, it’s a safe bet that were Wilson still with us today he would have flatly rejected Bush’s foreign policy. And with a few possible exceptions—the liberal intellectuals Paul Berman and Michael Ignatieff come to mind—Wilson’s heirs in the Democratic Party have vigorously opposed it. Bush has not even gained the backing of the New Republic‘s neo-liberal editors. This is not really very surprising, since if Bush is an idealist of sorts he is certainly no Wilsonian. Leave aside some of the obvious ways in which Bush violates the Wilsonian spirit: his rejection of the Kyoto Protocol, the International Criminal Court, and the land mine treaty; his refusal of NATO assistance in the Afghanistan intervention; his go-it-alone approach to Iraq. Bush is a unilateralist, not a Wilsonian internationalist. But even his “idealism” varies greatly from what passes for idealism on the Left today.

Bush believes in the promotion of democracy, but his conception and implementation of this goal is at once too broad and too narrow to please modern-day idealists. One of Bush’s most persistent themes is the universalism of human rights. “We [Americans] believe that liberty is the design of nature,…[and that] it is the right and capacity of all mankind,” he remarked in a November 2003 address. As James Ceaser and Daniel DiSalvo pointed out in the Public Interest (Fall 2004), the linkage of human rights and nature’s design draws on early modern political thought. One hears in the invocation of nature’s design an echo of the Declaration of Independence’s “Laws of Nature and Nature’s God,” not Woodrow Wilson, who was himself a great critic of the natural-rights underpinnings of the American Founding.

The broadly universalist thinking behind the Bush Doctrine is anathema to modern liberals in general and to the Democratic Party’s foreign policy establishment in particular. Of course, liberal foreign policy thinkers believe in human rights; but they are unlikely to see rights as nature’s, much less God’s, design for human beings. Rights are said to be a kind of social construct in the service of certain cultural, political, or class interests, for example, of the bourgeoisie. Having supposedly demystified natural rights, the Left is more likely to speak of certain economic rights, like the right to health care, or certain cultural rights, such as the right to self-determination. They tend to view “human rights” as in fact a cultural preference of Westerners, and thus Bush’s championing of democracy can appear to them as a form of imperialism or chauvinism.

But if Bush’s foreign policy is too universalist for modern liberal tastes, it can also seem too particularistic. Crucial to classical idealism is the priority of justice over self-interest or mere national security. Woodrow Wilson considered the emphasis on self-interest as not only unfair to others but degrading to ourselves. As he put it in his famous Mobile, Alabama, speech of October 27, 1913:

It is a very perilous thing to determine the foreign policy of a nation in the terms of material interest. It not only is unfair to those with whom you are dealing, but it is degrading as regards your own actions…. Human rights, national integrity, and opportunity as against material interests—that, ladies and gentlemen, is the issue we now have to face.

Many decades later, President Jimmy Carter would make a similar point in his renowned Notre Dame address of May 1977. He chided Americans for their “inordinate fear of Communism”—that is, their preoccupation with national interest—and instead urged them to put “the new global questions of justice, equity and human rights” at the center of U.S. foreign policy.

Bush shows none of the liberal idealist’s antipathy for the material interests of the nation. Indeed, in Bush’s view, there is a strong link between the promotion of democracy abroad and our safety at home. In his defense of the Iraq war, he has stated: “America’s interests in security and America’s belief in liberty both lead in the same direction: to a free and peaceful Iraq.” And speaking more generally of the war on terror he has argued: “We seek the advance of democracy for the most practical of reasons: because democracies do not support terrorists or threaten the world with weapons of mass murder.”

Bush’s promotion of democracy is selective, or we might say differently applied to different regimes and regions. His is no pure idealism, and in this sense, the Bush Doctrine is too narrow to appeal to modern-day idealists. In the Bush Doctrine, national interest seems to determine where and when the United States will promote democracy. Given Bush’s lofty Wilsonian rhetoric, such discretion is not always obvious. But consider the implications of his with-us-or-against-us policy, formulated at the very outset of the war on terror:

Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists. From this day forward, any nation that continues to harbor or support terrorism will be regarded by the United States as a hostile regime.

This policy has been widely denounced on the Left and the Right for its supposed simplicity and rigidity, but in fact it is just this policy that allows for considerable operational flexibility. A country like Pakistan, by breaking its links with al-Qaeda and assisting us in Afghanistan, came to be regarded as an ally in the war on terror—and without moving so much as an inch in the direction of democratic reform. But Arafat’s Palestine, by continuing to promote radical Islamist terrorism became exhibit “B,” only behind Iraq’s exhibit “A,” in Bush’s attempt to promote democracy. Such prudential application of absolute principles, all in the service of America’s self-interest, does not endear Bush to idealism’s liberal guardians.

Indeed, in the view of today’s self-styled idealists, Bush had gotten things exactly backwards. The Left views Pakistan’s General Pervez Musharraf as a thug, while they always lionized Yasser Arafat as the rightful representative of the rights of the Palestinian people. Their idealism dictated support for Arafat and, so to speak, regime change in Pakistan. Two important intellectual transformations made such quixotic judgments possible. First, by abandoning any notion of natural law, the Left was free to view Arafat’s terrorism as unimportant—or even as necessary in the struggle for Palestinian national liberation. To the Left, “Arafatism” was Idealism. Second, having rejected the legitimacy of national interest, the Left was free to overlook Pakistan’s strategic importance, as well as the pernicious effect of “Arafatism” on American interests in the larger Arab world.

Bush’s idealism thus breaks with the Left’s version on two crucial points: It is rooted in a universal standard of human rights or dignity, and it is tempered by prudential concern for our national security.

Preemptive Realism

If Bush is no idealist, does he belong to the party of realism? Certainly, one line of interpretation holds that Bush’s foreign policy of unilateralism, preemption, and power politics bears all the hallmarks of realism. But Bush himself has gone out of his way to criticize realism by name, and the truth is that his policies have possibly gained even less support from modern-day realists than from idealists. With a few possible exceptions—Henry Kissinger comes to mind, as does Fareed Zakaria at least in his initial support of the Iraq war—most realists have been aghast at Bush’s foreign policy. Both conservative realists like Brent Scowcroft, national security advisor under Presidents Gerald Ford and Bush I, and liberal realists like Zbigniew Brzezinski, national security advisor to Carter, have denounced the Bush Doctrine as something akin to heresy. The principal journal of foreign-policy realism, the National Interest, has become an increasingly fierce critic of the Bush Doctrine.

A major stumbling block for realists is, of course, Bush’s democratic faith. Owen Harries once stipulated, in his “Fourteen Points for Realists,” published in the the National Interest (Winter 1992/93), that the United States “should certainly not make the promotion of democracy a major—let alone the centerpiece—feature of its policy.” Realists just don’t go in for that sort of thing. But beyond that, even the more “realist” elements of Bush’s policy—preemption, in particular—have in some sense transcended the conventional realism of our day. And thus we should try to understand this element of the Bush Doctrine in particular.

According to the administration, the old international standard of preemption needed to be rethought to take account of the new terrorist threats. In the day when an adversary’s intentions were clearly visible in troop movements and the massing of armies, Daniel Webster’s 1837 formulation of preemption was perhaps adequate: there must be demonstrated “a necessity of self-defense…instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation.” The administration called for a new standard in its national security strategy:

We must adapt the concept of imminent threat to the capabilities and objectives of today’s adversaries. Rogue states and terrorists do not seek to attack us using conventional means. They know such attacks would fail. Instead, they rely on acts of terror and, potentially, the use of weapons of mass destruction—weapons that can be easily concealed, delivered covertly, and used without warning…. The greater the threat the greater is the risk of inaction—and the more compelling the case for taking anticipatory action to defend ourselves, even if uncertainty remains as to the time and place of the enemy’s attack. To forestall or prevent such hostile acts by our adversaries, the United States will, if necessary, act preemptively.

Iraq became the first test of the doctrine (though the Afghanistan operation was also arguably an instance of preventive war). On March 19, 2003, with the Iraqi intervention begun, Bush addressed the American people from the Oval Office. “We will meet that threat now, with our Army, Air Force, Navy, Coast Guard and Marines, so that we do not have to meet it later with armies of firefighters and police and doctors on the streets of our cities.” One could not have asked for a more succinct justification for preemptive war.

Looking Backward

What’s interesting is that Bush’s “new thinking” is in many respects based on some rather old thinking. The giants of the realist tradition, from Machiavelli to Alexander Hamilton, all defended preemptive (or really preventive) war. A quick look backward, therefore, might shed some light on the deepest meaning of Bush’s approach. Since we are discussing American foreign policy, let us take Hamilton as representative of the tradition.

A curious passage appears in The Federalist on the question of preventive war. In the course of making short work of complaints by Anti-Federalists that the Constitution lacked a provision against standing armies in peacetime, Hamilton quite unexpectedly turned to the larger question of war and peace. Two great transformations clearly troubled him. First, he warned in Federalist 24 that though the America of his day was protected by “a wide ocean” from hostile European powers, the country could not count on this good fortune to last for long. “The improvements in the art of navigation have, as to the facility of communication, rendered distant nations, in great measure, neighbors.” But neighbors, in his view, do not as a rule act neighborly towards one another. In Federalist 6, Hamilton had argued that it is an “axiom in politics that vicinity, or nearness of situation, constitutes nations’ natural enemies.” If one couples Hamilton’s concerns about the progress of technology with his “axiom of politics,” one reaches some rather sobering conclusions about war and peace. Far from the “perpetual peace” of Immanuel Kant’s dream, Hamilton forecasts a state of perpetual war, as technology brings nations into closer and more violent contact.

In Federalist 25, Hamilton marked a second transformation: the rules and practices of war are in flux. In particular, he observed, “the ceremony of a formal denunciation of war has of late fallen into disuse.” This would prove to be a serious development, but especially if the United States were to remain, as some leading Americans of Hamilton’s day desired, without a standing army or navy. Hamilton drew out the implications of their pacifist views:

The presence of an enemy within our territories must be waited for as the legal warrant to the government to begin its levies of men for the protection of the State. We must receive the blow before we could even prepare to return it.All that kind of policy by which nations anticipate distant danger and meet the gathering storm must be abstained from, as contrary to the genuine maxims of a free government (emphasis added).

The option of preventive war, which Hamilton only obliquely suggests here, he openly defended a decade later, when the two transformations that had concerned him were already well underway. In the late 1790s, revolutionary France had embarked on an undeclared “quasi-war” against the United States. Eventually, President John Adams would consider whether officially to declare war on France, and Hamilton was active in war preparations. He penned a series of newspaper columns that, not unlike The Federalist, were directed at American public opinion. In making his case against French aggression, Hamilton offered a truly sweeping defense of preventive war:

There is no rule of public law better established, or on better grounds, than that when one nation unequivocally avows maxims of conduct dangerous to the security and tranquillity of others, they have a right to attack her and to endeavor to disable her from carrying her schemes into effect. They are not bound to wait till inimical designs are matured for action, when it may be too late to defeat them. (From “The Stand,” April 4, 1798.)

Hamilton was surely exaggerating the consensus in public law on this matter. But what’s most significant for our purposes is that here, as in The Federalist, he makes no mention of imminence or the need for tangible evidence of hostile intent. The mere avowal of “maxims of conduct dangerous to the security and tranquility of others”—what today we might rather imprecisely call a hostile “ideology”—is enough, in his judgment, to justify preventive war.

Gathering Storms

Bush’s formulation to some extent echoes Hamilton’s. Neither Bush nor Hamilton emphasizes imminent danger, as would Daniel Webster. Quite to the contrary, the point for Hamilton, as for Bush, is distant dangers. Hamilton recommends a preventive war stratagem to meet “the gathering storm”—just as Bush over two centuries later would justify his preemptive strike on Iraq to meet “a grave and gathering danger.” It was a policy Bush would reaffirm in his otherwise “idealistic” Second Inaugural, calling it his “most solemn duty” to protect the country from “emerging threats.” Similarly, Bush’s emphasis in his Second Inaugural on tyranny’s universal threat is, in its way, a reflection of Hamilton’s warning against dangerous maxims. Both Bush and Hamilton show a keen awareness of the role ideas play in shaping reality and, ultimately, in determining the fate of nations.

Today’s realists, it is true, claim Hamilton as one of their own, but their realism is pinched by comparison. More so than their classical forebears, modern-day realists emphasize stability above all else while overlooking the powerful role ideals play in the shaping of human affairs. In his “Fourteen Points for Realists,” Owen Harries argued that America’s “principal concerns should be to maintain regional equilibrium and stability,” and he cautioned against “listen[ing] to those who sneer at the maintenance of stability, order, and equilibrium.” After America’s Iraq intervention, Harries lamented that America “has become the greatest revisionist force, the greatest agent of change, in the world.” Similarly, the liberal realist Zbigniew Brzesinski, in his book The Choice (2004), described the Bush policy of preventive war as “strategically regressive” and complained that it “lacks a balanced concern for order and justice.” To modern-day realists, the Bush Doctrine with its emphasis on democracy-promotion and preventive war seems destabilizing and dangerous: never mind that the doctrine itself was a response to the shock of September 11. That realists cleave, still, to a nonexistent pre-9/11 status quo bespeaks a certain naïveté, or even a certain kind of idealism. Perhaps this is one reason Bush in his addresses so often charges that those “who call themselves ‘realists'” have in fact “lost contact with a fundamental reality.”

Doctrinal Difficulties

Bush then is neither an idealist nor a realist. The president has artfully combined elements of both traditions, while at the same time transforming them. Perhaps most importantly, Bush’s “idealism” has sought to link the pursuit of national interest with the pursuit of justice, while his “realism” has led him to embrace the destabilizing policy of preemption. Bush is guided by idealist principles, to be sure, but their application depends, at least to some extent, upon the nation’s security requirements. After all, Bush has not invaded Cuba. In light of the challenges of September 11, Bush’s new approach is to be welcomed, and its successes are many. He has (so far) thwarted any further September 11-like assaults on this country, toppled two anti-American dictators, defanged another in Libya, and midwifed democratic elections in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Palestinian territories—all of which has apparently created a ripple effect, at least for now, in much of the Middle East.

But for all of its inventiveness the Bush Doctrine is not without its theoretical difficulties, and these tensions at the level of theory are felt, sometimes with serious consequences, at the policy and political levels. Let’s begin with the Bush Administration’s efforts to combine an idealistic policy of democracy-promotion with a policy of preventive war. The underlying assumption or hope of democracy-promotion is perpetual peace. The basic idea is that democracies don’t go to war with one another, and thus the spread of democratic principles and practices throughout the planet will enhance America’s security while leaving all countries better off. Yet as we have seen, the assumption underlying preventive war is nearly the opposite: a world of perpetual war, in which one’s guard must always be up.

Is it really possible to promote democracy in the name of world peace, while threatening preventive war? This is one of those theoretical conundrums that is perhaps less serious than it seems at first. The truth is that no politician can succeed in America who is not an optimist. The media clobbered George W. Bush when he suggested in the midst of the 2004 election that we faced an endless war on terror. “I don’t think you can win it,” he told Matt Lauer of the “Today” show. Bush’s comment was immediately labeled a “blunder,” and the president beat a hasty retreat the next day. One simply cannot say that kind of thing in a modern democracy and survive politically. After all, modern democracies, as Bush is wont to point out, are by their nature hopeful and peace-loving. Even as tough a fellow as Hamilton, living in a less sentimental age than our own, was unwilling to raise the prospect of preventive war directly. His discussion of it in The Federalist was, to say the least, circumspect. The following might be concluded: Perpetual peace is our hope, but until that day arises, preventive war will necessarily remain an option. One is reminded that a foolish consistency is indeed the hobgoblin of little minds.

Yet Bush’s promotion of democracy faces another difficulty, one that is not so easily finessed. Bush’s rhetorical emphasis is on democracy as the key to America’s security and world peace. He speaks frequently of “the great democratic movement” and “our commitment to democracy.” In these rhetorical tropes he is, one suspects, drawing on an idea usually associated with the late 18th and early 19th centuries that republics, unlike monarchies, are peaceful. In part the argument ran that if the people are given a say, wars fought for honor and glory will find few votaries. But a more central part of the theory was what became known as doux commerce—namely that the values and habits associated with commerce encourage peace. The emphasis of such philosophers as Montesquieu and Hume was on the commercial republic, not democracy per se. It was the new bourgeois man who would have little interest in war, so busy would he be to tending his self-interest. And then too the emphasis was on the representative republic, not pure democracy, since it was widely believed that the people en masse would act foolishly and rashly, following their passions rather than their true interests. The philosophers of the commercial, representative republic were too familiar with ancient history to be sanguine about democracy’s prospects. Athens may have been the world’s greatest democracy, but it was also belligerent in the extreme.

Taking Regimes Seriously

When Bush gets down to specifics about his democracy program, he’s almost always sure to discuss the place of commerce. His national security strategy devotes several pages to the promotion of “free markets and free trade,” and in his address to the National Endowment for Democracy he specified among the “essential principles” of a “successful society” privatized economies and the right to property. Bush has also made clear that by “democracy” he really means a liberal democracy, or a regime that embodies the rule of law, religious toleration, freedom of speech, and respect for women. But these details can be easily missed in his more sweeping calls for democracy and freedom. Elections by themselves do not overcome extremism. Iran is in many respects more “democratic” in terms of its political institutions and traditions than Egypt, but also far more dangerous to America’s security and world peace. In seeking to rally American and world opinion behind democracy, Bush risks adding to the confusion about what really matters: not simply elections but certain liberal and commercial habits of mind.

Despite these questions of emphasis, Bush’s program of democracy promotion is a welcome reminder that not all political regimes are the same, and that this has serious consequences for America’s security. The underlying thesis of Bush’s democracy policy is that regime type is of the utmost consequence. It’s more important to encourage democratic reform than to sign peace treaties or international agreements. Liberal democracies tend to keep their promises; tyrannies do not. In this regard, Bush’s policy shows an unusual awareness of how the world really works.

But strangely, for all of Bush’s emphasis on particular regimes and their characteristics, his administration seems to have thought little about America’s own regime, and how it might hinder Bush’s larger foreign-policy ambitions. If there is any country that typifies the commercial republic it is surely the United States. Americans have little taste for war. After nearly every major conflict, from World War I to the Cold War, the country has reduced its defense budget and defense preparedness. It is a striking fact that George W. Bush, who describes himself as “a war president,” has resisted efforts to increase significantly the defense budget or to enlarge the army. In the immediate weeks after the September 11 attacks Bush urged Americans to continue to go about their business, even to go shopping. This last comment was perhaps a gaffe on his part, but it was surely also a highly revealing one. It has been widely argued that up to 450,000 troops were probably needed in Iraq, but that the administration worried about gaining support at home for such a large force. Would Americans have stood for the necessary increase in troop levels, and would they have tolerated the possibility of greater casualties? This can be a hard thing to ask of a democracy, and the administration did not choose to put these questions to the test.

Justice and Necessity

America’s democratic character poses other problems for the Bush Doctrine. Historically, democratic and commercial peoples have been reluctant to face up to threats until the actual blow has been landed. It took a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor to open America’s eyes to the dangers of Nazi and Japanese aggression. Our response to al-Qaeda was initially of the same sort. September 11 was hardly al-Qaeda’s first assault on American interests, or even the American homeland, but the American public and its leadership chose throughout the 1990s to look the other way. Such democratic quietude raises questions about the feasibility of the Bush Doctrine over the long haul. Preventive war means responding decisively to emerging or partially hidden threats—threats that democratic peoples are loath to recognize.

One final difficulty with the Bush Doctrine: Even before the 2000 election Bush spoke of a “distinctly American internationalism”—by which he indicated his desire to break out of the old realism-idealism divide. Bush argued that we can best advance America’s security by acting on our ideals—that is, by advancing democratic principles throughout the world. After the September 11 attacks, this theme became especially pronounced. Bush argued increasingly that there is no trade-off between our ideals and our interests, that the two are mutually reinforcing or even one and the same. By the time of his Second Inaugural this had become the moral lodestar of the Bush Doctrine: “America’s vital interests and our deepest beliefs are now one.”

In so closely identifying America’s interests with her ideals Bush may have taken a step too far. One should be able to embrace the basic justice of our cause without claiming, as Bush has now done, that our self-interest is simply synonymous with our ideals. One of the great themes of Thucydides’ History was the tragic tension between interests and ideals or, in Thucydides’ formulation, between necessity and justice. The History is a long lesson in how necessity comes to predominate over nearly all else in the relations among states. Thucydides does not say that necessity always eclipses justice, but he certainly does suggest that political leaders will often be compelled to disregard justice strictly understood, in order to secure their community’s survival.

It seems unlikely that we Americans have suddenly cut this Gordian knot, and that in pursuing our interests or acting on our security, we will always be serving the larger cause of justice. As a nation that embodies in its founding understanding the rights of man, we may indeed be exceptional, and there may be less of a gap between our ideals and our interests than for most other states. Americans naturally tend to see in the triumph of human rights their own triumph, and vice versa. As they should. But Bush’s attempt to dissolve the tension between our interests and our ideals is misguided. Regretfully, occasions will arise when our leaders will be compelled to commit seeming or real injustices for the sake of the country’s survival. That this is an enduring, unpalatable truth of political life, especially in foreign relations, cannot be reasonably doubted by anyone. Our politicians should not be misled into thinking they have overcome this basic reality of political life, lest when the occasion arises, they lack the fortitude to do what is truly necessary.