Books Reviewed

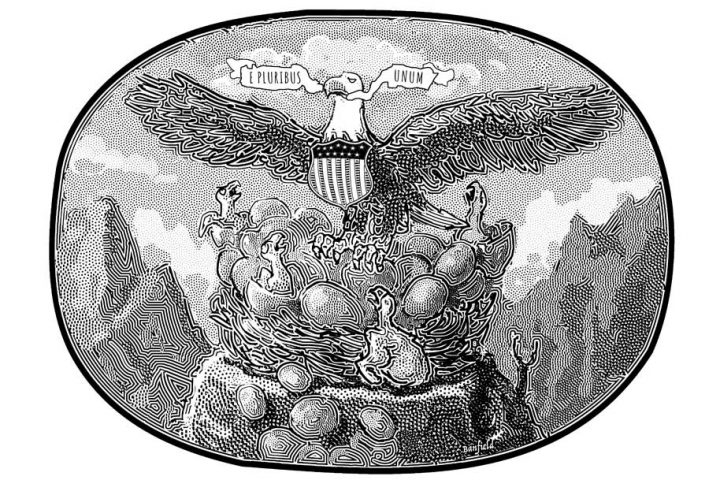

The American experiment seems to be going awry in unexpected and disturbing ways. Despite the health of the national economy, troubling signs abound: declining birthrates, family breakdown, rising mortality from suicide or drug overdose, social tribalism, political dissatisfaction, fraying social ties, and gnawing isolation. In Europe, Western civilization seems to be in an even worse state of decay.

Leon Kass’s new book, Leading a Worthy Life, has plenty of practical advice. A modern-day Renaissance man who has spent decades teaching the Great Books at the University of Chicago and St. John’s College, Kass has produced a revised and updated selection of previously published essays that diagnose how we’ve lost our way, from romance and marriage to sports, education, and the end of life. He makes a strong case that in America today our cultural practices are so disjointed and our social arrangements so unsatisfactory because too many of us no longer seek a life that reflects the dignity of mankind and the fullness of human experience.

* * *

Kass aims to remind us where we went wrong, by enunciating what many Americans “seek in their heart of hearts but have forgotten how to articulate or defend.” We’ve forgotten these things because we’ve become spiritually impoverished, mainly by mistaking freedom and prosperity for ends in themselves rather than means to a good life, to genuine human flourishing. We have forgotten, that is, what it means to be a human being. Kass argues that to wage war against this spiritual poverty we need better elites, and institutions that will inspire and sustain cultural renewal. But first, “we need a full-throated intellectual defense and celebration of what most Americans still tacitly know and live by. And this requires an account of why and how our most worthy practices answer to our deepest human aspirations and longings.”

So Kass takes us through some of those practices, beginning with a chapter on courtship (he isn’t afraid of antique terms like “courtship” or “bastard,” which help recall things we once knew). In a way, his discussion of courtship serves as a stand-in for a host of traditional practices that have disappeared from American life and have left young people adrift. He seems to have special sympathy for those trying to find their way into honorable adulthood. For all the talk of single parenthood and rampant divorce, Kass notes that there isn’t much discussion of what makes for marital success, much less “the ways and mores of entering into marriage, that is, to wooing or courtship.” But of course we don’t talk about wooing and courtship because they barely happen anymore, which is a big problem. “Today there are no socially prescribed forms of conduct that help guide young men and women in the direction of matrimony,” writes Kass, noting that it’s not just a problem for the lower classes. The reason for the loss of these practices is that we have forgotten, somehow, why people ought to get married in the first place. These days, anyone who knows a 20- or 30-something singleton who wants to get married knows what Kass is talking about. “[T]he way to the altar is uncharted: It’s every couple on its own, without a compass, often without a goal. Those who reach the altar seem to have stumbled upon it by accident.”

* * *

Kass has an idea of what needs to change, but most Americans aren’t going to like it. He recommends, among other things, “a restoration of cultural gravity about sex, marriage, and the life cycle,” the “restigmatization of illegitimacy and promiscuity,” and the “revalorization of marriage as both a personal and a cultural ideal.” To be sure, this is bitter medicine for a culture that has actively degraded both marriage and sex. Even among conservatives, it might only work if families quarantine themselves to some extent from the dominant liberal culture (as Rod Dreher called for in The Benedict Option). But Kass has a larger cohort of Americans in mind than just the very conservative and religious. His arguments are directed at Americans in the mainstream, too many of whom “are looking for reform on the cheap, a revival of good sense and decency in relations between the sexes without sacrificing any of the privileges and luxuries of modern life. We strongly suspect this is impossible.”

That frustrated desire goes for almost any subject in Kass’s book, not just courtship, marriage, and sex. Perhaps his most disturbing chapter is on dignified death and why doctors must not kill. Nothing demonstrates the monstrous logic of modern liberalism better than euthanasia, which Kass shows cannot be limited to a discreet class of terminally ill patients who freely elect it. He cites a Dutch government survey from 1995 that found doctors were already putting patients to death without their consent, justifying the practice for reasons like, “low quality of life,” “relatives’ inability to cope,” and “no prospect for improvement.” Pain and suffering were mentioned only about 30% of the time. The recent cases of infants Charlie Gard and Alfie Evans in the United Kingdom, both of whom the National Health Service deemed not to warrant continued treatment despite their parents’ wishes to seek treatment elsewhere, illustrate Kass’s contention that “the line between voluntary and involuntary euthanasia cannot hold, and it will be effaced by the intermediate case of mentally impaired or comatose persons who are declared no longer willing to live because someone else wills them not to.”

* * *

The source of the ills Kass addresses springs from an extreme application of Enlightenment principles divorced from the old moral order that once sustained them. We now have something altogether different from what the American Founders envisioned when they erected what was an inherently fragile system. Our constitutional order was not built for the present day’s moral relativism and untethered individualism, and setting things right will require more than turning the clock back to pre-World War II social norms, even if that were possible. Resolving the current crisis doesn’t hinge on this or that political policy (or any election cycle) but on the question of what is proper to a human being and what constitutes human happiness—that is, on a thoroughgoing reevaluation of how we live, as individuals and in community.

In the years to come, that will mean making concrete choices about a host of things like medical care, career advancement, religious practices, marriage and children. For those determined to reject the excesses of liberalism and live something closer to the old moral order, these choices will almost certainly come with a heavy cost. Leading a worthy life will most likely mean leading a less “successful” life, insofar as success is defined by the liberal mainstream. It might very well mean something much more severe.

Near the end of The Abolition of Man, C.S. Lewis says that nothing he can say will prevent some people from describing his lecture as an attack on science. He denies the charge, noting that in defending the very idea of objective value he is defending inter alia the value of knowledge, which would die, too, if the old order were completely swept away. So it is with Leading a Worthy Life. It’s easy to call Leon Kass an obscurantist and say he is clinging to a discredited moral philosophy that, after all, doesn’t “work.” But if we’re honest with ourselves about the state of modern society, we must insist, alongside Lewis, on a “regenerate science” that “would not do even to minerals and vegetables what modern science threatens to do to man himself.” To accept the totality of Kass’s claims and truly lead a worthy life is to change entirely how we see the world and the way we choose to live in it.