Books Reviewed

Four centuries and four decades after his birth, William Shakespeare not only remains the most compelling literary and cultural presence in our language but also attracts audiences and readers in the millions around the globe. Ben Jonson’s eulogy in the First Folio—”He was not of an age, but for all time!”—has become prophecy rather than exaggeration, and Shakespeare’s great competitor might have been astonished (and slightly chagrined) to find popular, professional, and scholarly interest in Shakespeare far more extensive today than it was in 1623. Stephen Greenblatt’s latest book acknowledges this phenomenon and attempts to provide an explanation for it by investigating the relationship between Shakespeare’s life and his writings:

A young man from a small provincial town—a man without independent wealth, without powerful family connections, and without a university education—moves to London in the late 1580s and, in a remarkably short time, becomes the greatest playwright not of his age alone but of all time…. How is an achievement of this magnitude to be explained? How did Shakespeare become Shakespeare?

Given the evidence of nearly unparalleled genius as a starting point, most explanations have focused narrowly upon the texts or, more broadly, upon the history of performances and audience reception rather than upon the author’s own story—and for good reason.

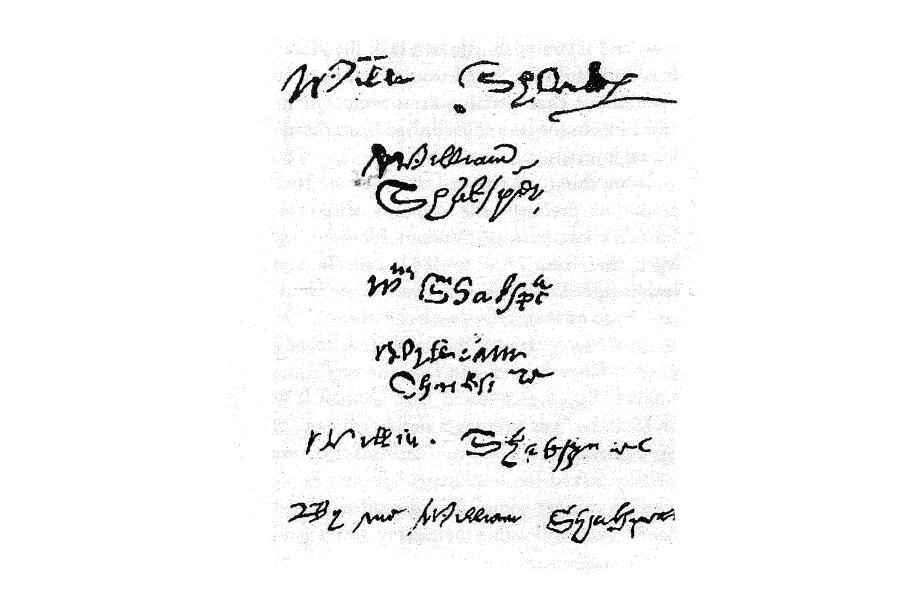

As Greenblatt acknowledges, any attempt to account for the genius by examining the life seems futile. We have no personal letters by and almost no direct contemporary testimony about William Shakespeare—even Jonson is writing about a collection of plays, not a man. Contemporary written records (including a mere six signatures by Shakespeare) consist of real estate transactions and other legal documents to which the playwright was a party. Shakespeare left no commentary upon any of his plays and didn’t even bother to publish them before his death. The only surviving personal document of any length is his will; the only substantial document written in his own hand may be a small portion of Sir Thomas More, a play with three co-authors that was probably never produced on stage. But no one is sure when Shakespeare’s portion may have been written, and a minority of scholars deny that Shakespeare wrote it at all. Shakespeare probably attended Stratford Grammar School, but there are no surviving records from that period. The birth of his twins Judith and Hamnet was recorded in Stratford in 1585, and in 1592 he was attacked in print as a successful London playwright by the dying Robert Greene: between those two notices, there are no records at all of the activities of William Shakespeare. Given all that we know about his works and the very little that we know about his extra-theatrical life, therefore, attempting to interpret the former by looking at the latter would seem to be not only futile but wrongheaded.

A biographical interpretation of Shakespeare’s works seems particularly unexpected coming from Stephen Greenblatt. As godfather of the literary-cultural practice known as “New Historicism,” General Editor of the Norton Shakespeare, and the subject of a collection of his own writings just published by Blackwell (The Greenblatt Reader), he has perhaps no equal within the American Shakespeare industry. Yet his own work and that of Renaissance literary critics over the past two decades has tended to efface the authority of individual writers or at least subordinate it to the influence of cultural practices, ideological discourse, and the requirements of language itself. At the end of Renaissance Self-Fashioning (1980), Greenblatt (presumably speaking for all of us) labeled as an “illusion” the notion that “I am the principal maker of my own identity.” More recently, he identified what he subtitled three “Portrait[s] of the Playwright as a Young Provincial” in his General Introduction to the Norton Shakespeare (1997) as examples of “the biographical daydreams that modern scholarship is supposed to have rendered forever obsolete.”

Each of Greenblatt’s own “biographical daydreams” is grounded upon documents identifying John Shakespeare, the playwright’s father, as an important public official in the borough of Stratford-upon-Avon and as a Roman Catholic recusant, and each imagines hypothetical scenes that Shakespeare may have experienced as a boy and adolescent: civil ceremonies in Stratford, a Royal Progress and Parliamentary election in Warwickshire, an exorcism in a Catholic household in 1580. Each anticipates both the method and the material that Greenblatt employs in Will in the World: “To understand who Shakespeare was, it is important to follow the verbal traces he left behind back into the life he lived and into the world to which he was so open. And to understand how Shakespeare used his imagination to transform his life into his art, it is important to use our own imagination.”

* * *

Whatever his professional discomfort with such fantasies, Will in the World is Greenblatt’s most readable and most engaging book to date. Yet it could not have been written without the more than two decades of literary and historical scholarship preceding it, not to mention the assumptions and methodology of that scholarship. Despite its intimations of Schopenhauer, Greenblatt’s punning title is resolutely down-to-earth and circumstantial, as is his portrait of the author. One of the book’s major themes is also the title of his final chapter: “The Triumph of the Everyday.” Shakespeare may have been the greatest dramatist of all time, but neither he nor his works ever repudiated or severed their connection with Stratford, the playwright’s first and final home. Shakespeare’s lack of university education or foreign travel is among the claims offered by those who doubt his authorship of the plays; Greenblatt not only acknowledges but celebrates Will’s connection with his homely roots and thereby provides ironically appropriate (if unneeded) dismissal of anti-Stratfordian skepticism.

Greenblatt’s excavation of the texts for biographically significant words, images, and references is nearly always persuasive, often inviting him to posit plausible real-life experiences that Shakespeare later revised and transmuted in the plays. For example, Greenblatt imagines the 11-year-old boy accompanying his father, then a local notable, to the entertainments associated with Elizabeth’s celebrated Progress to Kenilworth Castle, twelve miles northeast of Stratford, where he might have viewed for the first time the monarch in whose reign he flourished as a playwright. About 20 years later, a graceful compliment to the Virgin Queen in A Midsummer Night’s Dream almost certainly recalls that earlier appearance. Greenblatt imagines Shakespeare (June 1594) at the execution of Roderigo Lopez, the Queen’s onetime personal physician and a Jewish convert to Protestantism (The Merchant of Venice); Shakespeare (August 1596) at the funeral of his only son Hamnet (Hamlet); Shakespeare (August 1605) watching a theatrical performance by three schoolboys dressed like prophetesses welcoming King James during his first visit to Oxford (Macbeth). Greenblatt always acknowledges that these and other imagined scenes from the life are speculative, but in instances such as the Kenilworth celebration he notes that detailed contemporary accounts were available to Shakespeare whether or not he had been present. In other cases, he draws upon nonliterary documents (e.g., King James’s Daemonologie and other late 16th-century accounts of witchcraft), contemporary testimony and anecdotes, and a variety of actions and persons drawn from cultural, social, and political events during Shakespeare’s lifetime.

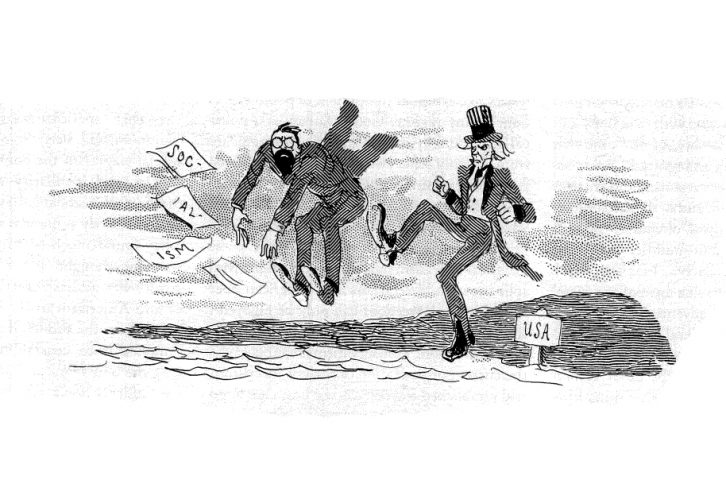

Shakespeare may indeed be a writer “for all time,” but Jonson would not have denied that he was also “of an age,” and that age is often the most compelling subject of Greenblatt’s book. Far from golden, Shakespeare’s age is here an anxious and oppressive era of persecutions, executions, and official and popular paranoia and xenophobia. “London was a nonstop theater of punishments,” according to Greenblatt, and Shakespeare’s plays often re-circulate and exorcise contemporary anxieties imaginatively.

The playwright’s own anxieties are presented in Will in the World as a product of ideological as well as personal circumstances. Greenblatt classifies them as social, religious and sexual, and interweaves them throughout his account of the life and the works. His conclusions are as firm as they are speculative. Shakespeare’s marriage to Anne Hathaway was not happy, he concludes. Symptoms of this dissatisfaction include the curious absence of mothers and wives and paucity of happy marriages in the plays, the removal of Shakespeare’s married life and disgust with his own sexuality in The Sonnets, anxieties about pre-marital sex in the late plays, the virtual erasure of his wife from his will and other legal documents at the end of his life, and his living apart from her during virtually all of his professional life. The greatest writer of romantic comedy in English, and one of the greatest love poets, apparently limited himself to celebrating the joys and frustrations of desire.

Greenblatt not only accepts the authenticity of John Shakespeare’s final Roman Catholic spiritual testament (found in the Henley Street house only in 1757) but is also drawn to accept whatever evidence is available that Shakespeare (as “William Shakeshafte”) worked in northwest England as a private tutor within wealthy Catholic households in the early 1580s before returning to Stratford and impregnating Anne Hathaway in the summer of 1582. That Shakespeare’s father was a secret Catholic and that his son may initially have been raised in the old faith and taught by Catholic schoolteachers prompts an illuminating and gripping account of the persecution and execution of recusant Catholics following Elizabeth’s excommunication in 1570 and the Jesuit mission of 1580. The torture, mutilation, execution, and public display of the severed heads of Lancashire and Warwickshire Catholics who might have been connected with Shakespeare and his family is a fact; the pro-Catholic sympathies of some Stratford Town Council members in the 1560s and 1570s is a likelihood; a personal encounter between Shakespeare and Edmund Campion, the Jesuit martyr who was circulating among the Catholic households in Lancashire that employed “Shakeshafte,” is one of Greenblatt’s fantasies. Nonetheless, his well-grounded historical sleuthing is used persuasively (if hypothetically) to account for significant effects upon the writer and his works: obliteration of any traces of religious or political beliefs in the personal effects, obfuscation or elimination of such beliefs in the plays, and Shakespeare’s ability in the plays both to occupy and to question all absolutist positions.

Ultimately, it is Shakespeare’s dream of advancement beyond the limits of his social station that Greenblatt focuses on most steadily in Will in the World. The son’s unimaginable ascent in the 1590s (and thereafter) trumped the father’s temporary rise in the 1560s but also enabled John Shakespeare’s public reputation to be redeemed. The one-time Stratford bailiff’s application for a gentleman’s coat of arms, set aside by the College of Heralds after his public reversal of fortunes in the 1570s, was renewed in 1596 and approved through the efforts of someone with the wealth, status, and connections to arrange for such instant ennobling. Greenblatt follows the scholarly consensus in identifying Will Shakespeare as his father’s proxy, but he also connects the family fortunes and Shakespeare’s own aspirations with a variety of his professional and personal characteristics: patterns of destitution and restoration in the plays, the poet’s personal parsimony and his ambitious projects to buy or lease real estate in and around Stratford from 1597 onward, even his early retirement as a Warwickshire squire, a “wealthy man with many investments,” after 1610.

* * *

Some of Greenblatt’s speculations will doubtless offend bardolaters or displease scholars less willing than he to invent scenarios or discover anxieties not evident in the documentary record. His often unflattering Will may seem mean-spirited coming from one who has profited so handsomely from his love of Shakespeare. Although Greenblatt shares Park Honan’s assumption that documents, like lives, cannot be properly understood apart from the world that lends them meaning, Will in the World does not provide the “continuous factual account” of Shakespeare’s life and works called for by Honan in his 1998 biography, which remains the authoritative life. Except for Greenblatt’s valuable (though occasionally opaque) discussion of how Shakespeare came to use “strategic opacity” to represent psychic inwardness in Hamlet and the plays that followed, there is virtually no discussion of Shakespeare’s development as a writer. Some speculations (e.g., Shakespeare’s father had a drinking problem and was one of the sources for Falstaff; Campion’s evasion of the authorities is reflected in Edgar’s shifts as Poor Tom) seem unnecessary as well as overly speculative.

Taken all in all, however, Will in the World exemplifies what Greenblatt himself calls “the special delight Shakespeare bestows on everything.” Vividly and lucidly written, it shows off New Historicist scholarship and criticism at its best. In particular, the chapters on The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, and Macbeth offer important, original, and accessible interpretations of these plays, and Greenblatt provides a compelling account of Shakespeare’s relationship with the brilliant but short-lived generation of Elizabethan playwrights whom he transcended (Robert Greene is another of his sources for Falstaff). Keats’s reflection in one of his letters that “Shakespeare led a life of Allegory: his works are the comments on it” necessarily must govern any attempt to pluck out the heart of William Shakespeare’s own mystery. Will in the World offers its readers a successful imaginative account that is about as tangible and substantial as they can have any right to expect.