Books Reviewed

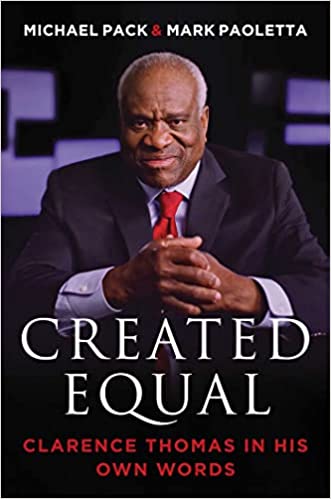

After Clarence Thomas’s bestselling 2007 autobiography, My Grandfather’s Son, followed by Michael and Gina Pack’s moving 2020 documentary, Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words, in which the Justice tells the camera essentially the same story, what need is there for this new volume of selected transcripts from the film’s interviews, also called Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words? Editors Michael Pack, the filmmaker who conducted the interviews, and Mark Paoletta, Thomas’s close friend and an ex-White House lawyer, write that most of the material is new, consisting of outtakes from the movie, but the life story recounted hasn’t changed. This book’s real novelty is the Justice’s discussion of jurisprudence, missing from the previous works, along with his reflections on social engineering and constitutional theory. These reflections are riveting, particularly after a Supreme Court term in which the judicial revolution—whose seeds Thomas has been sowing over his three decades on the Court—began to bear fruit in earnest.

In the Introduction, Paoletta rightly calls Thomas an American hero and our greatest Supreme Court Justice, and these pages detail the experience and thinking that formed so remarkable a judge. Remarkable, but also exemplary—both because Thomas believes that the Constitution’s central guarantee of liberty depends on the citizenry’s personal qualities of self-reliance and self-restraint, traits for which he is a poster child, and also because his own rise from poverty in the segregated Deep South to the High Bench illustrates the opportunity for self-development that liberty makes possible for Americans, both black and white. In particular, as he emphasizes in this volume, his story suggests what a different fate black America might have had if bad cultural developments and bad social policy, abetted by the Court, had not proved destructive to so many and led them to self-sabotage.

***

Born to a teen mother in the dirt-poor backwater of Pin Point, Georgia, and soon abandoned by his father, Thomas paints his earliest years as a Huck Finn idyll in the woods and swamps around the coastal hamlet founded by freed slaves. But when their kerosene-lit shanty burned down, his mother took six-year-old Clarence and his younger brother, Myers, a few miles north to a mean one-room flat in the Savannah slums, whose foul outdoor toilet the judge shudders to recall. Often cold and hungry, left unsupervised while his mother went out as a maid, Clarence didn’t always turn up at school. Chances are, he muses, that an unsupervised black Savannah slum child would grow up to be an uneducated slum adult.

But he was rescued. After a year, his overstressed mother sent the boys to live with her father and stepmother, Myers and “Aunt Tina” Anderson, only a few blocks—but a whole world—away, to a tidy house with a full fridge and magical plumbing that the boys gleefully flushed every time they walked by.

More dramatic was the moral transformation. As appears more clearly here than in earlier accounts, Thomas’s grandfather looked upon raising the two boys as a life’s work, molding their characters like an artist, to help them succeed. He and Aunt Tina always would say “that they weren’t going any further in their own lives,” the judge recounts, “but they were going to use the rest of their lives to raise their boys.” Illegitimate, orphaned early, and illiterate, Anderson was the incarnation of the self-made small entrepreneur, running a one-truck fuel-oil business, with the boys helping him make deliveries and his wife handling the office. Orderly and methodical, he had left the “jumping and…expressive stuff” of the black evangelical church to become a devout Catholic, at home in the church’s discipline. He paid the boys’ tuition to an all-black Catholic school, staffed mostly by Irish nuns, whose stern, demanding air only partly concealed a deep love that “can get you to do hard things,” Thomas recalls, and “force us not to fall into victim status.” After school, the boys went to work on the oil truck, its heater removed so they wouldn’t doze off in winter. They spent summers helping Anderson work a farm he owned across from where his own grandmother had been enslaved. They helped build a house, cleared land, strung barbed wire, plowed behind the frisky borrowed mare, and fed hogs, accompanied all the while by Anderson’s stock of maxims: “Don’t confuse want and need”; “You can give out, but you can’t give up”; “If you don’t work, you don’t eat.” Catholicism aside, this is the old-time Protestant ethic, a hard-headed mix of the moral and the practical.

***

For all its hardness, this upbringing was emphatically a labor of love, never voiced. Looking back, Thomas sees how freighted with feeling were the two nickels for milk his grandfather faithfully left for the boys each morning. “It almost brings tears to your eyes.”

Thomas began a lifetime of being the lone black in a white world when he started high school at a boarding academy for aspiring priests, and the sting of racism he sometimes felt there taught him to suppress anger. Fear of failure, strengthened by a wish to become bigotry-proof, made him strive first for success and then for perfection, so that any grade short of 100 disappointed him. He graduated to a Missouri seminary, where he found the racism more grating, at odds with the moral authority of the Church for whose priesthood he was preparing. When a fellow student met news of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s shooting with a wish that this black man of God would die, Thomas’s vocation died too, and he resolved to drop out. Shocked by his quitting, his grandfather turned him out of his house and refused to pay another tuition nickel elsewhere.

So when Thomas transferred to Holy Cross as a sophomore on scholarship in 1968, that ill-starred year of riots and political assassinations, he was a hurt and angry 20-year-old, in full ’60s rebellion. “For the first time in my life, racism and race explained everything,” he recalls. In April 1970, Thomas drove to Cambridge to protest the jailing of supposed black political prisoners and found himself participating, alcohol-fueled, in an all-night riot, complete with tear gas, smashed property, and injured cops and rioters. Sobered up back at Holy Cross, he recoiled from the “out of control” person he had become. His heartfelt prayer for deliverance from anger and hatred, he says, “was the beginning of the slow return to where I started.”

***

Enrolled in Yale Law, married to his college sweetheart (they divorced 13 years later), and soon the father of a son, Thomas began a years-long reexamination of his radical assumptions about race, which ended in a wholesale rejection of the War on Poverty and the ideology of victimhood and government paternalism that spawned it. He came to share his grandfather’s view that public housing was merely “tearing down neighborhoods and building buildings”—that government social programs were erasing civil society, the tissue of personal relations and private community institutions that teach and socialize, that instill the values that allow and impel people to rise, and that make moral judgments between the deserving and undeserving. Being a new father gave him a personal stake in the school-busing wars that roiled the TV news during his law school years. Why was Boston busing black kids from bad schools in Roxbury to equally bad schools in white South Boston and vice versa? It made no sense to Thomas, who thought it one more airy scheme dreamed up by social engineers who see the world in theoretical terms unanchored in social and individual reality. “I knew one thing,” he recalls: “nobody was going to have some social experiment and throw my son in there.”

Years later, as head of the Department of Education’s civil rights division, Thomas was still asking whether busing improved learning for black kids. There were no studies that answered that question, his senior colleagues told him—because the bureaucrats were never interested in education. Their reigning theory was that busing was a blunt instrument that would impel parents to move where their kids were going to school and thus foster neighborhood integration. “It was never about education,” Thomas marvels. That for decades urban public schools were about something else helps explain their failure.

His misgivings about the social engineers’ other educational nostrum, affirmative action, began even at Holy Cross, when he saw the shock of some of his fellow black students, especially those from inner cities, at their poor performance. After all, they had done well in their high schools, which hadn’t prepared them for the rigors of the selective Massachusetts college. Musing on their struggles, Thomas concluded that recruiting promising black kids to colleges beyond their aptitude or educational preparation does them harm, causing many to fail who would have succeeded on a less-demanding campus.

***

These ideas found mature expression in a series of Supreme Court opinions on racial preferences, one of which, his 2003 partial dissent in Grutter v. Bollinger, Thomas discusses in this book. In rejecting the University of Michigan Law School’s affirmative action admissions policy, the Justice dismissed the notion that racial discrimination can be constitutional. The Constitution and the 14th Amendment guarantee equal treatment to all citizens. In fact, he says, had he been on the court in 1954, he would have decided the landmark Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case differently, in a way that made such nostrums as “positive” discrimination unthinkable. Instead of declaring, as the Court did, that, in the special case of education, separate can never be equal, he would have invoked Justice John Marshall Harlan’s great 1896 dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, declaring that “Our Constitution is colorblind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” From that luminous principle, one can predict Thomas’s opinion in the upcoming Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard affirmative action case.

Thomas’s personal run-in with affirmative action upon graduation from law school doubtless hardened his views. He couldn’t find a job. Potential employers assumed that any black applicant must be an affirmative-action student and therefore suspect. After many fruitless interviews, he finally got an offer from Missouri Attorney General John Danforth, which classmates viewed as a sad comedown. Danforth turned out to be not only an ideal boss and later a great friend, but also Thomas’s route to higher things.

***

Handling criminal appeals in Missouri taught Thomas one more key lesson in his long deradicalization. “At the time,” he recalls, “I thought all blacks were political prisoners,” victims of a racist criminal justice system that wrongly jailed them at vastly disproportionate rates. And then he got the case of a black defendant who forced a black woman to submit to rape and sodomy by holding a blade to her little boy’s throat. Further investigation showed Thomas that “the overwhelming majority of violent crime is…black-on-black crime.” For him, that was a road-to-Damascus experience. The conclusion, ringing through a series of the Justice’s law-and-order opinions, is that fighting crime and disorder is a vital necessity for the law-abiding black majority, not a racist oppression.

In taking the Missouri job, Thomas had held his nose at working for a Republican, but he had no such qualms when Danforth, now a U.S. Senator, brought him to Washington as an aide in 1979. His new views had ripened, and he didn’t hesitate to air them at lunch with Washington Post reporter Juan Williams at a conference a few months later. He was so opposed to the current antipoverty orthodoxy, he explained, in part because he had seen what welfare had done to his elder sister, left behind to live with an aunt in Pin Point when his mother moved to Savannah with the boys. In a kind of natural experiment, she had missed out on the Grandfather-Knows-Best upbringing that had shaped her little brothers for success. Instead, she had been demoralized into dependency by the newly emerging welfare culture. To Thomas’s consternation, Williams then published a column on what Thomas hadn’t realized was an interview—earning him the ire of the civil rights establishment for wrongthink and bringing him to the notice of the Reagan White House, which recruited him to run the Education Department’s civil rights division in 1981 and in 1982 promoted him to head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

But a year after this fast rise, his grandparents’ deaths a month apart plunged Thomas, on the cusp of 35, into a life-crisis. “Why the hell are you even here?” he asked himself. What was he living for? As his turmoil eased, the answer materialized: to uphold his grandparents’ principles and his country’s—which he sensed were different versions of the same liberty-loving, self-reliant, created-equal creed.

***

Poring over the American Founding in informal seminars with his EEOC aides, Claremont Institute political theorists Ken Masugi and John Marini, turned out to be ideal training for a federal judge, which Thomas became when President George H.W. Bush raised him to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals and the Senate confirmed him in 1990. His nomination to the Supreme Court 16 months later sparked a confirmation battle of legendary nastiness, dramatizing just how high the stakes had become. It wasn’t only that his opponents feared that, if confirmed, he might vote to overturn Roe v. Wade, as he did this past term. They also feared that, as a conservative, he might favor the recently reinvigorated originalist school of constitutional interpretation, which could mean that the days when the Left could use the Supreme Court as a machine for achieving policy goals unwinnable in the legislature might be coming to an end.

You know the script, freshly familiar from the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation almost three decades later: at the 11th hour, Democrats magically produce fake charges of sexual harassment to smear the nominee as ethically unfit. Evidently the framers were not wrong to worry about the potentially unscrupulous power hunger of government officials. Certainly in 1991 the Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee, with Chairman Joseph Biden as their ringmaster (a dim, dishonest one, Thomas thinks), had no qualms about shredding the nominee’s reputation, which hasn’t recovered fully from the lies to this day, the Justice notes with asperity.

Indignant at the Democrats’ use of the hoariest racist blood libel about a black man’s sexual incontinence and their “cynical confidence that people would buy this implausible story,” along with their apparent belief that a black man had no right to independent thought that would lead from leftist orthodoxy to conservatism, Thomas famously called them on their sleaze, condemning their nationally televised ambush as a “high-tech lynching.” When the next day’s polls showed that the public overwhelmingly believed his obvious truthfulness, the full Senate could do nothing but confirm him.

***

Joining the court in October 1991, Thomas proved a rock-ribbed originalist, interpreting the words of the Constitution and laws as their framers, ratifiers, and contemporaries understood them. The written Constitution that safeguards Americans’ liberty to forge their own fates in their own way does not change. It doesn’t evolve by the slow accretion of judicial opinions, like the English system the founders rejected. Supreme Court decisions are opinion, not “settled law,” and they can be wrong. Though stare decisis, the doctrine that judges should respect precedent, provides stability, it is not an absolute command to Supreme Court Justices, who have a duty to overrule it when they think a precedent seriously in conflict with the Constitution, the fundamental law of the land.

Above all, originalism forbids Justices from substituting their own policy preferences for the words of the law, in the name of bringing about a higher justice or making the law consistent with the moral sense of the age. The Constitution’s careful separation of powers assigns that duty to the people’s elected legislators, not the judiciary. By the same token, even when they don’t like the policy consequences, Justices can’t dodge interpreting the law honestly, as in Thomas’s 2005 Gonzales v. Raich dissent, which denied that the Commerce Clause gives Congress the power to regulate medical marijuana that never leaves California. “Now, do I think people should be walking around smoking marijuana?” the Justice asks. “Not particularly, but that’s not the point.”

***

Toward the end of this book, Thomas notes the hostility to the framers and their Constitution of the early Progressives, led by college presidents Woodrow Wilson and Frank Goodnow. In place of the supposedly obsolete 18th-century document, Wilson wanted the Supreme Court to create a constantly evolving “living Constitution,” making up laws as new circumstances required. This is what the Justices have done for much of the past 80 years, by distorting the framers’ words to stretch the Commerce Clause to cover all economic activity, for example, or inventing such bogus doctrines as “substantive due process” to invent new rights out of thin air—a swindle that Thomas condemns in several opinions, including his concurrence at the end of this past term in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

But Wilson, Thomas emphasizes, also wanted to supersede the Constitution by creating a whole new extra-constitutional branch of government—the administrative state, in which supposedly expert executive branch agencies like the one Thomas ran for eight years make rules like a legislature, carry them out like an executive, and adjudicate and punish infractions of them like a judiciary. This wanton overturning of the constitutional structure of separated powers that protects our liberties, Thomas objects, replaces “government by consent with being ruled,” nullifying the great American political innovation that makes Americans citizens, not subjects. It’s a stark choice, he says, and already “there’s very little legislation that comes from the legislature. The legislation comes in the form of regulations from agencies,” regulations that now pervade our lives. Thomas began hammering away at this antidemocratic development in a series of 2015 opinions, aimed, like so much of his jurisprudence, at laying out a blueprint by which future Justices could correct past errors. Sure enough, Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority opinion in West Virginia v. EPA this past term, in which Thomas joined, followed his lead, sharply reining in the administrative state’s runaway rule by unelected bureaucrats.

All this is fascinating, though the terseness of the jurisprudence sections of this book, despite the editors’ copious footnotes, make them hard to appreciate fully without already knowing the Justice’s opinions. That’s why I’d pick the beautifully crafted movie and the polished My Grandfather’s Son over this volume. But there’s ample room for all three, for there can be no such thing as too much Clarence Thomas!