Books Reviewed

It was called the peculiar institution, partly because in a nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, slavery stood out as a contradiction and a dilemma. But by the middle of the 19th century, powerful politicians like Senator Stephen A. Douglas and Chief Justice Roger Taney were defining this fateful deviancy down, to the status of a peculiar variant of majority rule. According to their view of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, racial slavery and white supremacy were themselves founding principles, not temporary exceptions to those principles necessitated by the implacable realities of 1776 and 1787.

Many abolitionists shared this belief that America was constituted to allow for the unapologetic perpetuation of slavery. William Lloyd Garrison called the Constitution a “covenant with death and an agreement with Hell.” Garrison’s words echo in our own time, modern progressives having intensified their disdain for the founding by the multiculturalist belief that America is pervasively racist. For too many of today’s schoolchildren, the primary lesson about George Washington is that he owned slaves.

In Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July, James A. Colaiaco pushes back against this common view, siding with those who view slavery as the tragic flaw that haunts our country rather than the original sin that defines it. His book is an intellectual and oratorical biography, examining the famous black agitator’s political thought by analyzing Douglass’s major speeches from the decade preceding the Civil War. His point of departure is the oration Douglass gave on July 5, 1852, “What, To the Slave, Is the Fourth of July?” Colaiaco, who teaches Great Books at New York University, argues that this speech was a crucial event in American history—the greatest of all abolitionist speeches.

To substantiate that judgment, Colaiaco elaborates on the ceremonial, judicial, and political qualities of Douglass’s speech. It was conventionally ceremonial in its expressions of genuine admiration for the revolutionary and Founding Fathers and in its forceful linkage of the Declaration with the Constitution. It was also judicial, moving briskly from celebrating America’s origin to condemning its present. Meaning to shame and provoke his audience, Douglass confronted them as representatives of a nation of Pharaohs sprung from Hebrews. He denounced American (not merely Southern) slavery as an unparalleled violation of human rights.

Finally, the speech was political. Having converted to constitutional abolitionism the previous year, Douglass defended the Constitution before his audience as “a glorious liberty document,” going so far as to “defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it.” His radical conclusion, elaborated in editorials and speeches before and after his Fourth of July oration, was that the Constitution licensed and mandated direct federal action to effect slavery’s immediate abolition everywhere in the United States.

* * *

Colaiaco shows how Douglass became, after 1852, both more conservative and more radical in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Dred Scott ruling, and John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. In one respect, Douglass’s break with Garrison signified his embrace of constitutional reform rather than revolution. His former mentor’s position “expressed no intelligible principle of action,” whereas a program guided by the Constitution held the promise of real impact. On the other hand, as Douglass embraced the Constitution and rejected Garrison, he became more militant. Throughout the 1850s, he became increasingly convinced of the need for righteous violence. “The only penetrable point of a tyrant is the fear of death,” he remarked in June 1860. Whereas Thomas Jefferson had trembled at the thought that a just, vengeful God could not sleep forever, Douglass positively rejoiced in the hope that the day of reckoning was at hand.

Colaiaco directs attention away from racial identity, the focus of much recent scholarship on his subject, and back to Douglass’s primary concern with understanding and advancing the principles of natural justice and liberal republicanism in America. The book’s most interesting and provocative sections relate Douglass’s arguments to alternatives that shared his commitment to natural rights but differed about how to secure them. Most important were differences in constitutional interpretation. Characteristically, Douglass adopted a radical position, according to which: 1) no public enactment contrary to fundamental principles of justice could possess the binding authority of law; and 2) the key to understanding the Constitution was its text alone, especially its Preamble dedicated to high moral objects and its pointed refusal to grant explicit recognition to slavery.

Colaiaco provides the most complete exposition yet of Douglass’s constitutional abolitionism. But the author carries to an extreme his enthusiasm for the “strict-text” interpretive approach that Douglass employed. Identifying originalism with its grossly defective applications by Garrison and the Taney Court, Colaiaco gives too little attention to Douglass’s sketch of a challenging originalist argument. Colaiaco’s rejection of originalism leads him to associate Douglass with later proponents of the “living Constitution,” failing to note that this approach rests on principles contrary to those that Douglass shared with the founders. Most concretely, Colaiaco seems to accept Douglass’s radical claim of a constitutionally delegated federal power to abolish slavery directly, instantly, everywhere in the country—a reading unendorsed by anyone who signed or ratified the Constitution and one whose implementation would surely have provoked immediate civil war.

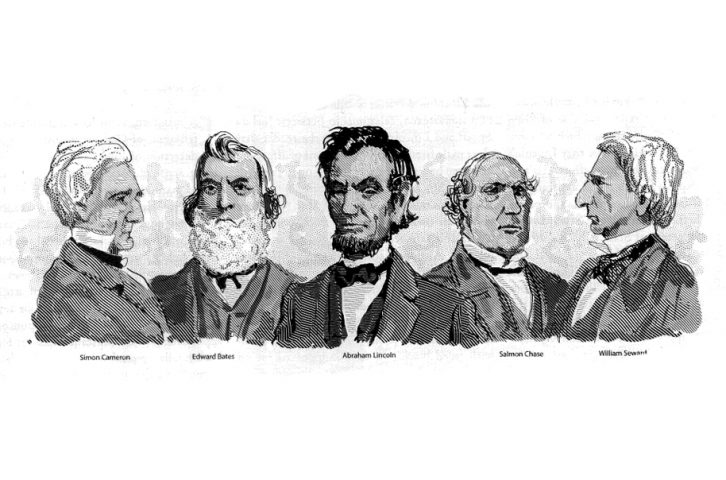

Colaiaco’s treatment of the relation between Douglass and Abraham Lincoln is also one-sided, giving Douglass the benefit of the doubt in all their disagreements. Douglass was often a severe critic of Lincoln’s relative moderation on slavery issues, from Lincoln’s (grudging) support of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law to his seeming insistence, prior to mid-1862, on a merely restorationist war. Even in 1876, in his speech dedicating the Freedmen’s Monument to Lincoln, Douglass saw fit to repeat his pre-Emancipation view of the martyred Emancipator. Alongside it, he developed and endorsed a contrary assessment, “taking [Lincoln] for all in all,” and Colaiaco does fairly summarize both views. Nonetheless, he approvingly quotes Douglass scholar Eric Sundquist, opining that compared to Lincoln, Douglass was “the truer son” of America’s revolutionary fathers. Whereas a bold and prophetic “Douglass had taken the lead on the problem of slavery,” a more cautious and passive “Lincoln had merely followed.”

But contrary to Colaiaco’s repeated claim, Lincoln’s prewar antislavery policy was not grounded in a passive hope that slavery, once confined, would eventually die a “natural death.” For Lincoln, slavery was to die by the hand of an active, antislavery statesmanship. It was to die by suffocation, forcibly confined in the atmosphere of condemnatory opinion in which he, Douglass, and others were laboring to envelop it. Further, Lincoln was scarcely less prophetic than Douglass in seeing the need for an abolitionist (not merely restorationist) war. Unlike Douglass, however, he saw that a premature declaration of an abolitionist war was likely to make victory impossible in a contest that would be supremely difficult under any circumstances.

* * *

Mainly for the better, Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July reflects the spirit of its subject and his age. Frederick Douglass deliberately styled himself a hero, in a period of our history distinctive in its celebration of heroes—a period of Romantic reaction against a spiritually flattening democracy, but also a period in which blacks’ capacity for heroism was commonly denied. In this book, in keeping with his own self-presentations, Douglass shines forth as America’s “gadfly”; he was “quintessentially the voice of black America”; he “stood like a titan among his contemporaries”; he was “majestic” in his wrath; and so forth. Present-day students of Douglass and of the period will likely judge, with justice, that the book inclines toward old-fashioned hero-worship. One searches in vain for mention of a significant shortcoming in Douglass’s public arguments and actions. But this is a pardonable fault in a work clearly meant to be inspirational as well as expository. In our own intellectual context, in which powerful egalitarian and postmodern currents move scholars to deflate heroes—or to conflate the heroic with the merely transgressive—Colaiaco’s frank recognition of his subject’s genuine nobility is refreshing.

In the end, though Colaiaco fails to establish Douglass as the truest son of the American revolutionary fathers, he succeeds admirably in showing how Douglass is properly paired and partnered with Lincoln: the Great Agitator and the Great Emancipator, post-founding America’s two greatest defenders and renovators of the indispensable principles of natural rights liberalism. More particularly, at a moment in our history when the malady of alienation from America’s moral and civil life has reached crisis proportions among young black males, Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July performs a vital service in reviving the moral spirit of America’s greatest exemplar of black manhood. Douglass distinguished himself most profoundly from other intellectually formidable black leaders of his day, and beyond, by his unconquerable hopefulness, together with his self-overcoming love for his country and the principles to which it is dedicated.