Books Reviewed

Two hundred years after his birth, Walt Whitman is still alive and well. “[L]ook for me under your bootsoles,” he once intoned, “Missing me one place search another.” And he isn’t that hard to find: we’re all familiar with his best-known poem “O Captain! My Captain!” from the 1989 film Dead Poets Society. In 2009, Levi’s advertised blue jeans using the one audio recording believed to be of Whitman’s voice, reading some lines from his poem “America.” You can read a 2016 detective novel starring Whitman. This year, Michigan’s Bell’s Brewery began releasing a seven-beer series honoring Whitman’s poems. The U.S. Postal Service has announced a new commemorative stamp, and I even found a Whitman magnet at a street market: a cartoony Walt broods over a bowl of breakfast cereal, the box labeled “O Captain! My Captain Crunch!”

For the bicentennial, scholars have gathered in New York and Paris, and Americans have hosted public readings, performance art, and festivals to celebrate his life and works. But for some conservatives, Whitman remains something of a pariah for his unorthodox poetics, his questioning of organized religion, and his expressions of same-sex desire. It doesn’t help that he has been adopted as the poet laureate for the Left. But amidst our cultural polarization, his bicentennial could also be a moment of ceasefire. He was an innovator who celebrated equality and dignity, who helped our nation grieve during the Civil War, and who beautifully articulated the experience of being human. These are things on which we should all agree, and it’s time for all of us to return to our American Bard.

Barbaric Yawp

Born to working-class parents on Long Island on May 31, 1819, Walt Whitman descended from Dutch and English stock, and his great-grandfather had served under John Paul Jones in the American Revolution. Educated only to age eleven, Whitman nevertheless read voraciously. He went to work in a law office and as a typesetter—getting an early exposure to printing and publishing. Providing for himself from a young age—his father was a failed housebuilder and likely an alcoholic—he taught school, which he hated, and tried his hand unsuccessfully at politics, before devoting himself to journalism. He lived in New York and briefly in New Orleans, writing local-color sketches, reviews, and op-eds. He published some conventional poems, short stories, and the occasional pot-boiler—writings that formed what Ralph Waldo Emerson later called the “long foreground” to his 1855 book, Leaves of Grass.

When he published that book of poems, Whitman was 36 and largely unknown in the literary world. The volume didn’t really help—by all accounts it sold almost no copies. Readers confronted a strange, large-format green book with no author’s name on the cover. Inside they found the now-famous engraving of Walt in workmen’s clothes, hand on hip, his hat cocked jauntily, as he gazes frankly at his readers. After a long prose preface whose first word is “AMERICA,” the opening line of the untitled first poem, later called “Song of Myself,” announces: “I celebrate myself.” Even the meter provokes: Whitman begins with iambic feet—the dominant rhythm for poetry in English since the days of William Shakespeare and John Milton. But he cuts it off after three metrical feet, never reaching the prescribed five of iambic pentameter, and the poem never returns to it. The break with regularized meter, although with some antecedents in William Blake, had begun in earnest.

In 12 untitled poems, full of epic catalogues and long experimental lines, Whitman sounded his “barbaric yawp” (his term) and celebrated the full range of human experience, the dignity and beauty of creation, the soul, and his beloved America. Bridget Bennett, in her introduction to the beautiful new Macmillan Collector’s Library edition of selected poems from Leaves of Grass, calls it “a poetic Declaration of Independence.” Over his long life, Whitman revised and expanded Leaves of Grass into a massive book, organized largely into thematic “clusters” of poems, and he published it in six distinct editions.

Reviews of the first edition were mixed, mostly perplexed, and occasionally savage. The cantankerous Rufus W. Griswold, who as Edgar Allan Poe’s literary executor had devoted himself to slandering the deceased author, wrote anonymously of Whitman in the weekly Criterion: “[I]t is impossible to imagine how any man’s fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth, unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love.” Those were the good old days for book reviews.

An Equal Place

Hostile critics foamed against Whitman’s experimental form and his frank portrait of the human body, but some initially failed to recognize that at the heart of this strange, unruly book was Whitman’s artistic working-out of the Declaration’s claim that “all men are created equal.” “I am the poet of the woman the same as the man,” his opening poem declares, “And I say it is as great to be a woman as to be a man.” Readers then and now have struggled to make sense of his seemingly disorganized epic catalogues of American life. Yet these catalogues dramatize his interpretation of this founding principle in poetic form:

The bride unrumples her white dress,

the minutehand of the clock moves

slowly,

The opium eater reclines with rigid head

and just-opened lips,

The prostitute draggles her shawl, her

bonnet bobs on her tipsy and

pimpled neck,

The crowd laugh at her blackguard oaths,

the men jeer and wink to each

other,

(Miserable! I do not laugh at your oaths

nor jeer you,)

The President holds a cabinet council, he

is surrounded by the great

secretaries….

These lines juxtapose the highest and lowest members of white society, images of bridal purity with drug use, the presidency with prostitution. Whitman, who would elsewhere condemn prostitution as degrading, still refuses to place these persons into hierarchical order: in the American republic, as in emerging American art, everyone has an equal place. His vast catalogues form a cinematic montage that includes women, men, children, immigrants, people of various and mixed races, and disabled persons. “I will not have a single person slighted or left away,” he writes.

Because of this project of equality, Whitman wrote some of the most powerful anti-slavery poetry in American literature. In a vivid passage of the poem later titled “I Sing the Body Electric,” he turns a slave auction—which he had likely witnessed in New Orleans—into a dramatic assertion of human dignity. In a rhetorical coup, his speaker insists that the value of the slave in fact far exceeds his price on the auction block. The auctioneer of slaves “does not half know his business,” and the poetic speaker seizes the stage: “Gentlemen look on this curious creature, / Whatever the bids of the bidders they cannot be high enough for him.” “Examine these limbs, red black or white,” he exclaims, “Within there runs his blood…the same old blood…the same red running blood.” And in a startling move, the poem prophesies that this person legally for sale might become the father of “populous states and rich republics.”

If many political leaders of Whitman’s republic sought to compromise on the question of slavery, his book would not. The speaker in “Song of Myself” aids and abets a runaway slave, “putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles; / He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and passed north.” Whitman wrote in his prose preface to the 1855 edition, “The attitude of great poets is to cheer up slaves and horrify despots.”

Body Politic

What has consistently startled critics and readers since 1855, however, is not so much Whitman’s democratic vision as his frank celebration of sex and the body. Emerson begged him to censor the earthier poems in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, but Whitman stubbornly refused. Sure enough, his book’s sexual content got him fired from a government job in 1865, and in 1882 the book was banned in Boston.

But his treatment of sex and the body reiterates his democratic principles. If everyone stands equal within the body politic, the same must be true within the human body. “Welcome is every organ and attribute of me,” his speaker says, “and of any man hearty and clean, / Not an inch nor a particle of an inch is vile, and none shall be less familiar than the rest.” Whitman’s verse elevates bodily life: “I keep as delicate around the bowels as around the head and heart,” he writes, “Copulation is no more rank to me than death is.”

Although it shocked his 19th-century audience, it was nothing truly new. Homer, Geoffrey Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Jonathan Swift had already explored the combination of awkwardness and sublimity that being an embodied spirit entails. But Whitman emphasizes beauty, joy, and innocence rather than the limitations and discomforts that informed the bawdy humor of his literary ancestors. The poems of his “Children of Adam” cluster marvel at the beauty of the human form, male and female, and celebrate the joyful union and generative power of sex, “Singing the song of procreation.” The title of Whitman’s cluster evokes Eden, and on the question of sex he sides with Milton, who in Book IV of Paradise Lost added to the Genesis account those “rites / Mysterious of connubial love” in the Garden. Even for fallen humans, Milton insisted that sex remains holy, and his epic narrator denounces “Whatever hypocrites” would go “Defaming as impure what God declares / Pure.” For all his posture of originality, Whitman planted himself firmly in this tradition.

Flesh and Blood

Much has been written about Whitman’s articulation of his own same-sex desire. In the homoerotic “Calamus” cluster, and in his private writings, the poet expressed his longing for what he called “the need of comrades.” Indeed, he never married, and had close, loving friendships with younger men, particularly the Irish-born ex-Confederate Peter Doyle. Late in life, Whitman tantalized one disciple with the promised revelation of a deep secret, but never delivered. He also claimed (probably falsely) to have had six illegitimate children, none of whom was ever found.

The published “Calamus” lyrics originate in a 12-poem manuscript sequence that Whitman never published, known as Live Oak, with Moss. Newly reissued with manuscript images and illustrations by Brian Selznick, best known for The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007), these private poems articulate a conflicted desire for male intimacy. The speaker expresses longing, exaltation, despair, shame, and the pain of unrequited love. Karen Karbiener’s foreword draws fascinating links to Shakespeare’s sonnets, and Selznick’s illustrations range from the truly beautiful to regrettable male erotica.

This vision of intimate male love, in Whitman’s mind, could be the deep bond of friendship needed to unite the nation. In “For You O Democracy,” his speaker proclaims that he “will make the continent indissoluble” and “will make inseparable cities,… / By the love of comrades, / By the manly love of comrades.” He first published the poem in 1860, when the nation seemed neither loving nor quite so indissoluble.

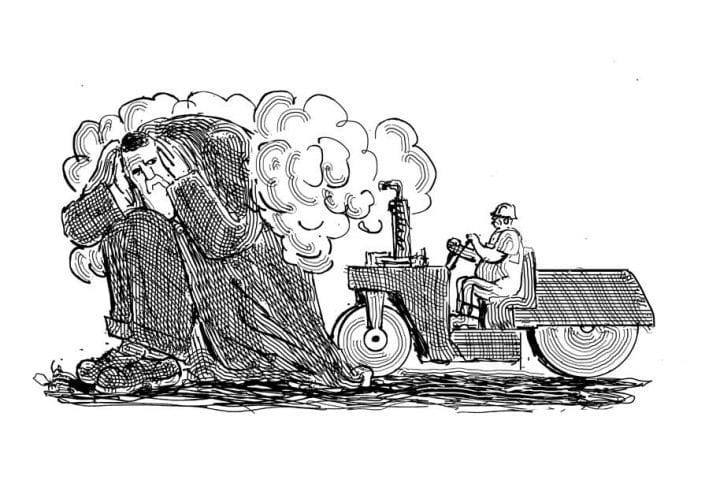

Whitman never forgot his first real encounters with the Civil War. When his brother George was wounded at Fredericksburg, Whitman went to the front to find him. Outside a field hospital, he recalled seeing “a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart.” These severed body parts acted out in flesh and blood the divisive conflict of our Civil War, and the poet of American optimism would have to grapple with the horrific suffering of this dark period.

He began visiting the wounded, sick, and dying soldiers that filled the Union hospitals. Though never a combatant, he experienced the costs of war firsthand and up close during his hospital work: he estimated that he had visited between 80,000 and 100,000 men, and described in one memoir that his notebooks were spotted with blood. In the wards of D.C. and New York, he sat with the men, sometimes late into the nights, bringing them ice cream, tobacco, and books. He listened to their stories and struck up fast friendships, providing the human companionship and morale-boosting that were essential to recovery. And just as important, he mourned these men when they died, helping their families to grieve. Many soldiers died in these hospitals far from home and family, and Whitman would sometimes write to the bereaved parents about the last days of their sons.

Keeping Vigil

The anonymity of some of these deaths horrified him. In the era before dog-tags and DNA testing, countless men died unknown, blown to pieces on the battlefield, rolled unceremoniously into mass graves, or left unidentified in the hospitals. As historian Drew Gilpin Faust recounts in her brilliant book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (2008), these men were also denied what American culture believed to be the “good death,” a version of the old ars moriendi (art of dying) that prescribed a preparation for, and acceptance of, death. Because of the dislocations of the war, the surviving family, too, was denied some of the rituals of burial and grief. In the face of this cultural catastrophe, Whitman and other American writers set out to provide a literary good death and mourning that could stand in and help the nation to grieve.

In his magnificent elegy, “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night,” Whitman’s poetic speaker keeps an all-night “Vigil of silence” for a “son” and “comrade” on the battlefield. As in almost all of the poems of his Civil War cluster “Drum-Taps,” the soldier remains nameless, and thus can stand in for any one of what Whitman later called “The Million Dead.” The speaker calls it a “Vigil strange” because the war necessitates improvised mourning practices, and this funeral wake takes place not in a home but on the battle-scarred field. Critics have noted that Whitman’s repetition of the word “vigil” becomes a kind of liturgical chant, and that the poem itself becomes a burial rite for the unknown dead, a fixing in our memory of those who might otherwise be forgotten:

Vigil for comrade swiftly slain, vigil I

never forget, how as day brighten’d,

I rose from the chill ground and folded

my soldier well in his blanket,

And buried him where he fell.

Through imagination, Whitman offers a symbolic personal mourning and burial for some—or all—of the more than 600,000 dead.

With Abraham Lincoln’s shocking assassination in April 1865, Whitman transferred this national mourning to the slain president. Living in D.C. during the war, he had often seen Lincoln from a distance, and treasured the memory of the day he caught the president’s eye, and Whitman’s hero “bow’d and smiled” to him. In “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” he grieves the dead president as “the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands.” In his much-anthologized “O Captain! My Captain!” he figures Lincoln as a victorious but fallen ship’s captain. This rare metered-and-rhymed poem mourns in singsong verse the contrast between the Union’s joy in the victory and the loss of Lincoln:

Exult O shores, and ring O bells!

But I with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

For all its success, the ballad is not his best poem, and later in life Whitman humorously lamented that the public loved it so much. When a critic suggested that he should have written more like it, he told a friend, “I’m honest when I say, damn ‘My Captain’ and all the ‘My Captains’ in my book!” “I’m almost sorry I ever wrote the poem,” he groused, and complained that if that poem were considered his best work, “God help me! what can the worst be like?”

Do Not Prettify Me

After the war, Whitman’s health was never the same: he endured terrific stresses during his hospital volunteering, and was exposed to countless diseases and infections. In 1873, he suffered a stroke that left him partly paralyzed. He moved to Camden, New Jersey, where he would live until his death in 1892. Although extremely poor—even supported by charity—and at times quite incapacitated, he still wrote constantly, revising, expanding, and republishing Leaves of Grass, memoirs, and other works.

In Camden, Whitman met and befriended Horace Traubel, a young socialist intellectual who would launch one of the most ambitious projects in American biography: over the last four years of Whitman’s life, Traubel visited the ailing poet nearly every day, and wrote down everything he said. Although the nine volumes of With Walt Whitman in Camden can be found as searchable text on The Walt Whitman Archive, The Library of America has done a great service by condensing this massive, rambling record into a single useful volume, Walt Whitman Speaks. Edited by Brenda Wineapple, the book collects the most interesting of Whitman’s remarks, organized under headings like “Literature,” “Friendship,” “Nature,” and “Democracy.”

“[D]o not prettify me,” he instructed Traubel, “include all the hells and damns.” Indeed, what emerges from this lovely book is the everyday Walt: opinionated, jovial, looking back on his life and work. We get his colorful, off-the-cuff remarks on other writers. “Milton soars,” he says, “but with dull, unwieldy motion.” Of Edgar Allan Poe: “morbid, shadowy, lugubrious.” Henry James: “only feathers to me.” George Eliot: “a great, gentle soul, lacking sunlight.” Though aged and infirm, Whitman reflects on his own enduring optimism: “I stand for the sunny point of view—stand for the joyful conclusions.” Of Leaves of Grass he says it “is an iconoclasm, it starts out to shatter the idols of porcelain worshipped by the average poets of our age.”

As an iconoclast, Whitman has often attracted the attention of progressives and radical movements. But there’s always a risk in recruiting authors to current ideological causes, as Karbiener’s foreword to Live Oak, with Moss does when it puts Whitman in the context of “today’s LGBTQ rights movement” and the 1969 Stonewall riots. Calling Whitman “the first gay American of letters” is to map a very narrow label from today’s identity politics onto a complex, unique American artist. It’s not that these labels aren’t true, but they’re not true enough to capture a human being’s breadth and richness. As a writer and as a man, Walt Whitman called for unity and magnanimity during his own troubled, divisive times. His poetry speaks all voices, embraces all peoples: “I am large,” he famously wrote in “Song of Myself,” “I contain multitudes.” Still, Whitman was a feisty, independent spirit, a self-proclaimed “rowdy” and “an American, one of the roughs,” who enjoyed provoking his readers. “I have always craved to hear the damndest that could be said of me,” he told Traubel, “and the damndest has been said, I do believe.”