Books discussed in this essay: The American Presidents Series from Times Books

The publication begun in 2002 of the American Presidents Series by Times Books is an important event. Well-known historians, often authors of authoritative biographies on their subjects, have produced treatments both readable and brief, usually 150 to 175 pages long, distilling the most important aspects of each president's formative experiences, political rise, term in office, and post-presidential years. Mostly unadorned by footnotes and unconcerned with the minutiae that occupy so many of today's biographers, the American Presidents Series gets to the heart of the matter for a popular readership.

The aspiration of the series is to provide an "easy education in American history," as the late Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., the series editor, wrote in a note that forms the preface to each volume. Teaching American history through biography has advantages, bringing figures both heroic and unheroic alive. What's more, American politicians don't ascend to the presidency by being unrepresentative. Accordingly, the way presidents engage political controversies illuminates what Americans wanted during those years. This clarification of context is indispensable to understanding what is distinctive about the American political order as it has been revealed through our history.

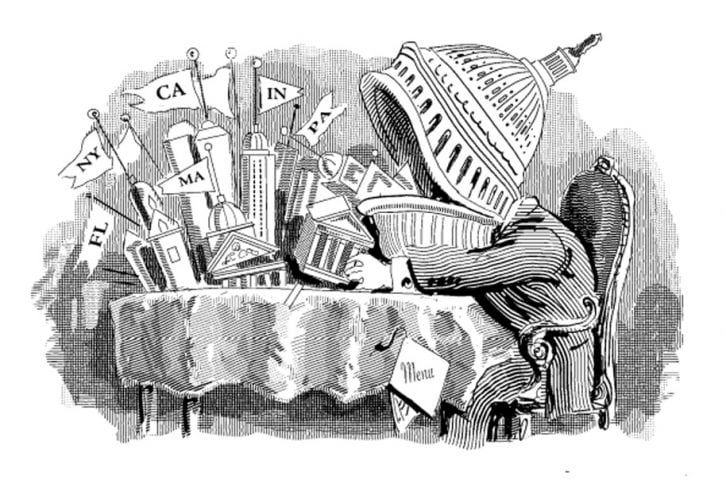

The trouble with viewing political history merely through the prism of presidents' biographies, however, is that policy debates can appear to be grounded in nothing deeper than the people's changing needs and the government's changing capacities. This approach reflects the conviction, integral to progressive politics and scholarship, that American democracy has a history but not really any principles, at least not any permanent or essential ones that might constrain and direct the relation between government and the citizens. The American Presidents Series presents, in short, a narrative of the inexorable growth of the state that makes limited government and constitutionalism increasingly irrelevant.

As Woodrow Wilson put it, "governments have their natural evolution and are one thing in one age, another in another." "Governments are what politicians make them," he argued, and so "it is easier to write of the President than of the presidency." Easier, but not better. Which is why it's surprising that, in spite of itself, the American Presidents Series provides a basis for challenging two central aspects of the progressive narrative.

Chronicles and Olympian Historians

When Schlesinger died in 2007, Princeton historian Sean Wilentz became editor of the Series. He has yet to select authors for volumes on Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama. (And the volumes on John Kennedy, William Henry Harrison, and William Howard Taft are not available, yet.) Some pairings of biographer to subject are natural fits, such as Robert Remini's John Quincy Adams, Wilentz's Andrew Jackson, the late Roy Jenkins's Franklin Roosevelt, and H.W. Brands's Woodrow Wilson. Some are emphatically not, like George McGovern's Abraham Lincoln. The volumes on the presidents since FDR are more concerned with settling partisan scores than fulfilling the Series's central mission. Tom Wicker's Dwight Eisenhower and Elizabeth Drew's Richard Nixon don't even pretend to be fair.

History, of course, is more than a chronicle of "one damn thing after another." Honest chronicling is an indispensablepreparation to writing history, which brings, however, a critical perspective to the record and endows events with meaning. By explicating principles or tensions that define the human condition, historians connect isolated events to one another, and to larger contexts that reveal their import.

For example, Lincoln's great Peoria speech in 1854 chronicled the American government's measures touching on slavery, with the aim of showing that the founders put slavery on a course toward its ultimate extinction. Lincoln's history is controversial, especially in light of the late historian Donald Fehrenbacher's claim that the functioning Constitution had effectively rendered America a "slaveholding republic." Yet Lincoln's speech assimilated evidence into a historical narrative arguing persuasively that the Kansas-Nebraska Act was a radical departure from our constitutional order's essence. Franklin Roosevelt provides another enduring, powerful story—the progressive narrative that many of the Series's historians embrace and even take for granted. In his "Commonwealth Club Address" during the 1932 campaign, FDR portrayed American history as the rise and fall of economic opportunity. For centuries, according to FDR, ruthless kings forged strong, central states "able to keep the peace" but eventually went too far, giving rise to popular movements, such as the American Revolution, committed to natural rights and limited government. Individualism thrived as long as labor was scarce and land plentiful.

The Industrial Revolution and the closing of the frontier imperiled these happy conditions. By the 1930s, FDR claimed, "equality of opportunity as we have known it no longer exist[ed]," as evidenced by the precarious lives endured by many Americans. He called for a "re-appraisal of values," culminating in an understanding that "financial Titans," like the feudal kings before them, had made their contribution to historical progress by building out the modern industrial plant. Now, "the day of enlightened administration has come," in which the job of government will be "modifying and controlling our economic units" by re-working the Bill of Rights to include economic or social rights.

Many writers in the American Presidents Series adopt and elaborate FDR's story, making the central drama of American history the interplay between "the people" and "the powerful." In the early republic, runs this account, government succored the powerful through such policies as John Adams's Alien and Sedition Acts, Nicholas Biddle's Bank of the United States, and the Whigs' American System. The people needed their champions, finding them in Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. After the Civil War, the bad guys were greedy businessmen like FDR's "economic royalists." The good guys responded by empowering government. This formula allows former Clinton advisor Ted Widmer to call FDR, who expanded government, an "ideological descendant" of Martin Van Buren, who constrained it. When writing about the 1830s, Widmer and Wilentz are constantly thinking about the 1930s. The moral is clear and simple. Presidents who failed to augment government's capacity to regulate or redistribute wealth were prisoners of their times. Those who succeeded at expanding government were farsighted statesmen who helped lay the groundwork for the New Deal.

Examples are plentiful. Though James Ceaser has shown convincingly that Van Buren founded the modern party system mostly to fulfill the founders' goal of restraining popular leadership, the eighth president emerges in Widmer's account as someone who founded political parties to increase the institutional capacity of extra-constitutional national institutions. Rutherford B. Hayes recognized the growing gap between rich and poor, which makes him "an early progressive," in Hans. L. Trefousse's view, though Hayes was merely a "child of his age" when he failed to intervene on behalf of fledgling labor unions. For Zachary Karabell, Chester Arthur's signing of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act reflects the "impulses that would coalesce in the early twentieth century to create the Progressive movement." William McKinley emerges from class-warrior Kevin Phillips's volume as a "surprisingly modern" president who believed in positive government—and may have grown further in office had he lived. Even the most conservative president of that time, Grover Cleveland, "foreshadowed the antitrust fervor," according to Henry F. Graff's interpretation.

These judgments reflect the complacent assumption that any measure requiring stronger government must be interpreted as anticipating and advancing the progressive cause, rather than as reflecting the application of America's constitutional principles to changing realities. Similarly, the authors insist that any concern with economic inequality points forward to progressive policies of redistribution. Civil service reform is an early echo of the omnipotent administrative state, instead of a sensible limitation on a spoils system that, taken to its extreme, upsets executive energy. Trust-busting appears as something that can be justified only on progressive grounds.

The volumes on the 19th-century presidents generate great anticipation for Wilson and FDR. What emerges from Brands's Woodrow Wilson and Jenkins's Franklin Delano Roosevelt is therefore a bit of a letdown: the New Freedom and the New Deal are nothing revolutionary or even programmatic, but a series of unconnected attempts to solve society's problems. Brands's Wilson is someone whose actions speak louder than his words, even though Wilson's writings were his most fundamental actions. Brands sees progressivism merely as a "congeries of reform which encompassed all manner of worthy causes, from conservation and corporate regulation to consumer protection and immigration restriction, from prohibition and workmen's compensation to women's suffrage and primary elections." For his part, Jenkins sees neither the well of ideas from which FDR drew nor the objectives toward which he was heading, though he does admit that FDR would not have ranked among the great presidents absent World War II, since Roosevelt only "semisuccessfully" pulled "America out of the Great Depression." In truth, Brands and Jenkins don't care enough about Wilson and Roosevelt's ideas to understand, really, these presidents' sweeping ambitions.

Progressive Expectations

Schlesinger's editor's note contains a typically progressive critique of the constitutional system. "The tripartite separation of powers has an inherent tendency toward inertia and stalemate," he declared, and only the executive is "structurally capable of taking that initiative" to resist the gridlock. This makes the presidency the vital place of leadership, as presidents possess and are possessed by "a vision of an ideal America." How presidents come to have such a vision is vitally important, so an investigation of their background and experiences seems in order.

"I remain to this day a New Dealer," Schlesinger wrote in his memoirs, A Life in the 20th Century, published in 2000, "unreconstructed and unrepentant." In his scholarship as much as his politics, to whatever extent the two are distinguishable, Schlesinger was always mindful of FDR, believing presidents informed by the best social science (or at least social scientists) of the day can be expected to know the best answers to the public policy controversies they confront. These assumptions about the crucial role of executive leadership are woven into the book series. Government must be designed to bring the right sort of leaders to the presidency, and provide for a president's ability to impose his views on Congress and the nation.

Yet the biographies in Schlesinger's series do not bear out this theory of the presidency. In fact, the biographers commendably, if unwittingly, do more to vindicate the founders' vision of a flexible system than to prove the need for Schlesinger's progressive Constitution. Often it appears that public policy problems simply cannot be solved by vesting the president with sufficient power to work his magic.

Between Wilentz, who catalogues the economic folly of Andrew Jackson's effort to destroy the Bank of the United States, and Widmer who describes Van Buren's uncomprehending reaction to the Panic of 1837, one must recognize that flawed policies sometimes emerge because flawed leaders cannot ascertain wiser policies. Like many recent treatments of the New Deal, Roy Jenkins's volume shows that FDR's plan did not revive the economy, and that the president had no real idea how to do so. Blaming the constitutional separation of powers for problems actually caused by insufficient knowledge is typical of the progressive worldview, but the pages of the Schlesinger series show, despite themselves, that presidential leadership simultaneously vigorous and based on a sure grasp of all the relevant facts and theories is by far the exception, not the rule. The idea that the legislative branch is the part of the system thwarting a dynamic presidency is also refuted by the stories told in these volumes. Henry Clay forged the Missouri Compromise with behind-the-scenes help from James Monroe. Chester Arthur was a spectator as Congress passed the Pendleton Civil Service Act. Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act after Stephen Douglas provided decisive political leadership from Capitol Hill. Congress passed Reconstruction legislation over Andrew Johnson's vetoes. Clearly, the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue can also be the "vital center" of action and innovation.

Nuggets of Narrative

None of my complaints about the biographies as history should gainsay their excellence as chronicles. Nearly every volume contains a fact one appreciates learning. Widmer shows how the term "OK" emerged from Van Buren's re-election campaign of 1840, when "Old Kinderhook" added the letters to his signature to conjure up memories of "Old Hickory." John S.D. Eisenhower relates in Zachary Taylor that "Old Rough and Ready" is considered by some eminent historians to be the only man who might have averted the Civil War, and Eisenhower makes that seemingly far-fetched statement almost plausible. Franklin Pierce was, as Michael Holt writes, "the most handsome man ever to serve as president of the United States."

Remini's John Quincy Adams and Josiah Bunting III's Ulysses S. Grant are two of the best volumes, each rehabilitating its subject's reputation. Remini portrays a nagging, controlling Abigail Adams, the only American until Barbara Bush who was one president's wife and a second one's mother. Abigail's ability to make her children's lives miserable appears to have been a significant factor in her son's decision to volunteer for several foreign diplomatic missions. (His less fortunate siblings met early deaths that Remini connects to their mother's meddling). This domineering Abigail contrasts with the sweet, ironic one seen in David McCullough's bestselling biography of John Adams. By afflicting her son, Abigail helped America gain a skilled diplomat and visionary statesman. Though Remini lends credence to the conventional view that John Quincy was an apolitical, nationalist president ill-suited to the Jacksonian Zeitgeist, the author shows how Adams effectively guided American foreign policy from 1800 to 1828, always with an emphasis on containing slavery while expanding the geographical ambit of freedom. Gary Hart's surprisingly subtle James Monroe corroborates this view, arguing that the Monroe-Adams partnership was crucial to America's "self-definition" as an anti-imperial, expansionist power.

Bunting's Grant faces a sterner challenge, for Grant's presidential reputation is one of corruption, incompetence, and vacillation on the important issues of the day. Bunting's slender volume gives full scope to the difficulties Grant faced as president and his earnest public-spiritedness in dealing with them. He came to office facing "a set of political challenges together more severe than those that have greeted all American presidents save only two"—Lincoln and FDR. Grant sought to "protect the freedmen" and "conciliate the South" at a time when the facts on the ground rendered these goals utterly incompatible. The protection of civil rights depended on executive enforcement as the means of preserving "the legacy of the terrible war that [Grant] had fought under the leadership of Abraham Lincoln." Enforcement of civil rights would require, in effect, long-term occupation of the South. When the army retreated the Southerners reverted to their old ways. Yes, Grant "vacillated," applying and relinquishing the pressure as exigencies demanded. What alternative did he have? Prevailing histories have been quietly pro-Southern in their inability to recognize this "almost insoluble" dilemma that Grant tried, yet failed, to overcome.

Two of the oddest choices in the series are former Senator George McGovern to write Abraham Lincoln (a volume originally assigned to E.L. Doctorow), and Ira Rutkow, M.D., to write James A. Garfield. The choice of McGovern, a strident Democratic partisan who earned a Ph.D. in History from Northwestern University, is immediately suspect, though it appears Larry Mansch, author of a fine book on the months between Lincoln's election and his inauguration, ghostwrote the volume. (McGovern admits his own limits as a writer and thanks Mansch "for his assistance in both the research and the composition of the book.") What emerges, however, is a genuine achievement—a well—told, even beautiful account of Lincoln's rise to the presidency, moderate constitutionalism, steely adherence to the Declaration of Independence, and shrewd wartime leadership. McGovern depicts a president dedicated to natural rights and a proponent of equal opportunity, not a simple precursor of FDR or Wilson. The story of Lincoln's assassination is told with uncommon pathos and drama.

Rutkow's biography of Garfield emphasizes the medical aspects of the 20th president's assassination and death. Garfield, the fourth of six presidents who had served as an officer during the Civil War, achieved the rank of brigadier general. Upon entering Congress he joined the Radical Republicans in pushing Lincoln toward a more exacting policy toward the defeated Confederacy. As Northern opposition to radical Reconstruction mounted after Grant's election, Garfield moderated and supported pulling federal troops out of the South and a less vigorous enforcement of the civil rights bill. To say, as Rutkow does, that Garfield's opinions on the military's role in Reconstruction "never varied" is incorrect, and the story of how Garfield changed his mind is an interesting, revealing part of Reconstruction. Such subtleties would distract Rutkow, who concentrates on the medical mishaps leading to Garfield's sad, avoidable demise 200 days after his inauguration. The president's attending doctor, Willard Bliss, was a Civil War surgeon whose old methods, distrust of then—current medical research into antisepsis, bacteria, and sterilization, and insistence on complete control of Garfield's recovery, led to the president's infection and death. The emphasis on the odd circumstances of Garfield's death is a missed opportunity in a series otherwise focused on political history.

Toward a Constitutional History

The failings of the American Presidents Series are instructive, reminding us of the need for a constitutional history of the United States premised upon the importance of first principles. Essential elements of such a history would include an awareness of the limits of human understanding and an appreciation for the context of statesmanship. Too often the Series's authors assume our presidents' fundamental task is to expand the state and liberate humans from the permanent problems and tensions of political life.

In reality, administration is seldom as enlightened as it needs to be and certainly far less enlightened than progressive historians assume it can be. Aware of the problems of monopoly, favoritism, and corruption, the American Founders advocated limited government, knowing full well there would be controversies about constitutional boundaries. The superior political history we need would treat, seriously and respectfully, the problem of deciding where to establish these boundaries in concrete cases, rather than proceeding from the hoary assumption that every politician's effort to expand government hastens the arrival, in Schlesinger's words, of "an ideal America."